The Jordan Rules’ Was the Mother of All Woj Bombs

Remembering Sam Smith’s scandalous, detail-laced, seemingly impossible chronicle of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls in the early 1990s, 25 years later

What, you’re still watching the NBA Finals? Right after Steph Curry turned into Curly Neal, I went over to my bookshelf and pulled down a volume that’s quietly enjoying its 25th anniversary. It’s called The Jordan Rules. It was written by Sam Smith in 1991. It was a simpler time. We didn’t have Woj bombs, but we made do.

How to understand how much mind-blowing, Woj-like reporting is stuffed into The Jordan Rules? Let’s turn to page 95.

It’s November 1990. Michael Jordan and the Bulls — on the bumpy road to their first NBA title — arrive in Oakland to play the Warriors. They learn that the Lakers’ James Worthy was arrested for hiring two prostitutes. “You’d think he’d have been tired of being double-teamed by now,” one of the Bulls jokes.

That night, the Bulls lose to the underdog Warriors. Jordan gets just 12 shots — a result, he thinks, of the triangle offense that coach Phil Jackson has used to take some of his points and redistribute them to other players. (Jordan calls the process “de-Michaelization.”) “He kicked a chair when he came into the locker room,” Smith writes.

“I hope they keep playing you that way,” Don Nelson, the Warriors coach, says to Jordan.

At a club that night, Jordan seethes with embarrassment. “I hate when I have to read that in the papers the next day, that I couldn’t do something,” he tells another player. The next day, at practice in Seattle, Jordan shows up Jackson by refusing to take more than a shot or two. “Michael wouldn’t say a word to anyone,” Horace Grant says.

The same night — such is the granular depth of The Jordan Rules — Jordan goes to another nightclub and runs into a motormouth Sonics rookie named Gary Payton. “I’ve got my millions and I’m buying my Ferraris and Testarossas, too,” Payton brags.

“No problem,” Jordan replies. “I get them for free.”

Payton’s mouth is all it takes to reactivate Jordan’s murderous instincts. Against the Sonics, Jordan takes the ball away from Payton the first two times he touches it. Payton is so thoroughly owned that he has to go to the bench. But just as Jordan is gliding toward a SportsCenter-worthy night, Jackson pulls him out of the game. De-Michaelization and all.

“He’s not going to let me win the scoring title,” Jordan whines to guard B.J. Armstrong as he sits on the bench.

We started on page 95, remember. Though Smith has sloughed off enough behind-the-scenes gossip for two ESPN The Magazine features, we have read to only page 97. This is why we made due without Woj bombs back in 1991. Because The Jordan Rules was the mother of all Woj bombs.

am Smith was an odd guy to write a classic sports book. A veteran of the Chicago Tribune’s general assignment desk, he was a nebbishy, mustachioed workhorse who drifted into sports. David Axelrod — the Tribune columnist turned Obama political guru — said Smith favored saddle shoes like the ones Archie Andrews wore.

The Tribune sports department was filled with native Midwesterners who felt like they’d reached Valhalla. Smith, who was from Brooklyn, was more clear-eyed. If his writing occasionally groaned under the strain of the beat — in The Jordan Rules, he compared the Bulls to the defenders of the Alamo, General Sherman, and the British army during the Revolutionary War — he had a knack for finding the killer detail. Smith took an advance of about $60,000 from Simon & Schuster to write a chronicle of the Bulls’ ’90-’91 season.

His editor was Jeff Neuman, who five years before had published John Feinstein’s A Season on the Brink, a book that changed the trajectory of sports nonfiction. First, A Season on the Brink rescued basketball books from the racist baggage they’d been carrying around. Second, it created the template for the literate, feverishly reported “season inside.” In an amazing five-year run, Neuman edited Skip Bayless on the Cowboys, Chris Mortensen on the mob and the NFL, Don Yaeger and Douglas S. Looney on Notre Dame, and Terry Pluto on the ABA.

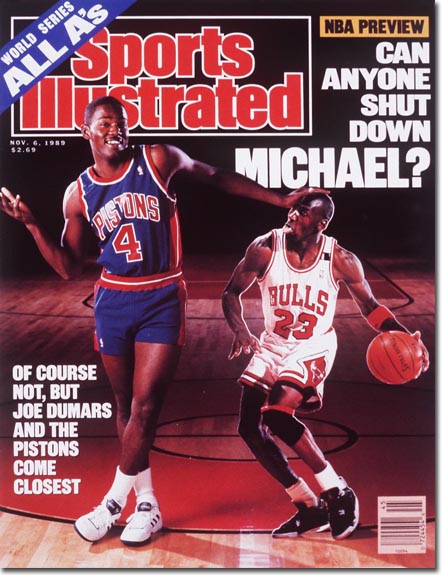

By 1990, the smiling pitchman for Nike and McDonald’s was a perfect subject for muckraking. With only a touch of irony, Playboy called Jordan “the quintessential gentleman, consummate sportsman, clean-living family man and modest, down-to-earth levitating demigod.” Jordan’s image was so tied to his affability that he once told reporters he had a frequent dream: He had made an off-the-court mistake, and his Q score had dropped, and all his doubters said, “I told you so.” “It’s like they’ve been waiting for it and now it’s here,” Jordan said.

The real Jordan, Smith found, was thornier, less smiley. “He often backed away from the traditional leadership role,” Smith wrote in The Jordan Rules, “and … he rarely spoke with his teammates other than to taunt them with his rapier wit.” Though the word wasn’t used this way in the ’90s, Jordan was an enormous troll.

In the 1990 playoffs against the Pistons, Scottie Pippen had been leveled by a migraine headache before Game 7 — a humiliating event for a young player. When the Bulls lost to the Pistons the next spring and Pippen played badly, Jordan said, “Headache tonight, Scottie?”

Remembering Sam Smith’s scandalous, detail-laced, seemingly impossible chronicle of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls in the early 1990s, 25 years later

What, you’re still watching the NBA Finals? Right after Steph Curry turned into Curly Neal, I went over to my bookshelf and pulled down a volume that’s quietly enjoying its 25th anniversary. It’s called The Jordan Rules. It was written by Sam Smith in 1991. It was a simpler time. We didn’t have Woj bombs, but we made do.

How to understand how much mind-blowing, Woj-like reporting is stuffed into The Jordan Rules? Let’s turn to page 95.

It’s November 1990. Michael Jordan and the Bulls — on the bumpy road to their first NBA title — arrive in Oakland to play the Warriors. They learn that the Lakers’ James Worthy was arrested for hiring two prostitutes. “You’d think he’d have been tired of being double-teamed by now,” one of the Bulls jokes.

That night, the Bulls lose to the underdog Warriors. Jordan gets just 12 shots — a result, he thinks, of the triangle offense that coach Phil Jackson has used to take some of his points and redistribute them to other players. (Jordan calls the process “de-Michaelization.”) “He kicked a chair when he came into the locker room,” Smith writes.

“I hope they keep playing you that way,” Don Nelson, the Warriors coach, says to Jordan.

At a club that night, Jordan seethes with embarrassment. “I hate when I have to read that in the papers the next day, that I couldn’t do something,” he tells another player. The next day, at practice in Seattle, Jordan shows up Jackson by refusing to take more than a shot or two. “Michael wouldn’t say a word to anyone,” Horace Grant says.

The same night — such is the granular depth of The Jordan Rules — Jordan goes to another nightclub and runs into a motormouth Sonics rookie named Gary Payton. “I’ve got my millions and I’m buying my Ferraris and Testarossas, too,” Payton brags.

“No problem,” Jordan replies. “I get them for free.”

Payton’s mouth is all it takes to reactivate Jordan’s murderous instincts. Against the Sonics, Jordan takes the ball away from Payton the first two times he touches it. Payton is so thoroughly owned that he has to go to the bench. But just as Jordan is gliding toward a SportsCenter-worthy night, Jackson pulls him out of the game. De-Michaelization and all.

“He’s not going to let me win the scoring title,” Jordan whines to guard B.J. Armstrong as he sits on the bench.

We started on page 95, remember. Though Smith has sloughed off enough behind-the-scenes gossip for two ESPN The Magazine features, we have read to only page 97. This is why we made due without Woj bombs back in 1991. Because The Jordan Rules was the mother of all Woj bombs.

am Smith was an odd guy to write a classic sports book. A veteran of the Chicago Tribune’s general assignment desk, he was a nebbishy, mustachioed workhorse who drifted into sports. David Axelrod — the Tribune columnist turned Obama political guru — said Smith favored saddle shoes like the ones Archie Andrews wore.

The Tribune sports department was filled with native Midwesterners who felt like they’d reached Valhalla. Smith, who was from Brooklyn, was more clear-eyed. If his writing occasionally groaned under the strain of the beat — in The Jordan Rules, he compared the Bulls to the defenders of the Alamo, General Sherman, and the British army during the Revolutionary War — he had a knack for finding the killer detail. Smith took an advance of about $60,000 from Simon & Schuster to write a chronicle of the Bulls’ ’90-’91 season.

His editor was Jeff Neuman, who five years before had published John Feinstein’s A Season on the Brink, a book that changed the trajectory of sports nonfiction. First, A Season on the Brink rescued basketball books from the racist baggage they’d been carrying around. Second, it created the template for the literate, feverishly reported “season inside.” In an amazing five-year run, Neuman edited Skip Bayless on the Cowboys, Chris Mortensen on the mob and the NFL, Don Yaeger and Douglas S. Looney on Notre Dame, and Terry Pluto on the ABA.

By 1990, the smiling pitchman for Nike and McDonald’s was a perfect subject for muckraking. With only a touch of irony, Playboy called Jordan “the quintessential gentleman, consummate sportsman, clean-living family man and modest, down-to-earth levitating demigod.” Jordan’s image was so tied to his affability that he once told reporters he had a frequent dream: He had made an off-the-court mistake, and his Q score had dropped, and all his doubters said, “I told you so.” “It’s like they’ve been waiting for it and now it’s here,” Jordan said.

The real Jordan, Smith found, was thornier, less smiley. “He often backed away from the traditional leadership role,” Smith wrote in The Jordan Rules, “and … he rarely spoke with his teammates other than to taunt them with his rapier wit.” Though the word wasn’t used this way in the ’90s, Jordan was an enormous troll.

In the 1990 playoffs against the Pistons, Scottie Pippen had been leveled by a migraine headache before Game 7 — a humiliating event for a young player. When the Bulls lost to the Pistons the next spring and Pippen played badly, Jordan said, “Headache tonight, Scottie?”

at Jordan not going to the White House because he didn't vote for Herbert Bush

at Jordan not going to the White House because he didn't vote for Herbert Bush . Dope thread tho...

. Dope thread tho...