A Nation of Lawyers Confronts China’s Engineering State

As the Chinese economy surges forward, the U.S. has lost its capacity for physical improvement.

A Nation of Lawyers Confronts China’s Engineering State

As the Chinese economy surges forward, the U.S. has lost its capacity for physical improvement.

By Dan Wang

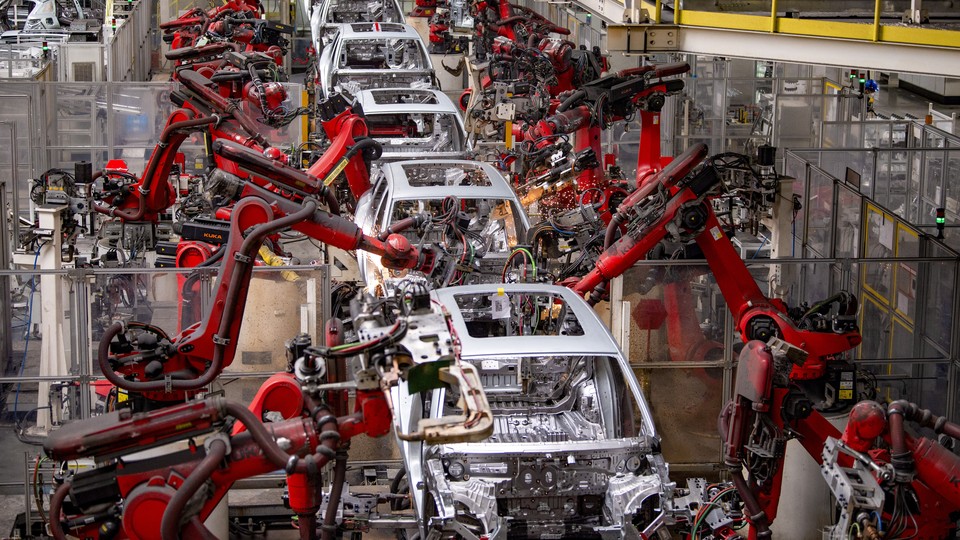

Hu Xiaofei / VCG / Getty Images

August 18, 2025, 6 AM ET

Listen to more stories on the Noa app.

After Donald Trump announced ruinously high tariffs on China in the spring, a simple reminder of that country’s growing technological power forced him to back down. Shortly after Trump’s April 2 tariff announcement, Beijing abruptly suspended exports of rare-earth magnets.

Automakers around the world panicked. These magnets—manufactured in Chinese factories from crucial metals extracted mostly from Chinese mines—have become essential for building cars. Ford Motor paused production at a plant in Chicago. Automotive-lobbying organizations in the United States and Europe warned that car companies were weeks away from halting production. A few reportedly were considering moving some production to China in order to maintain access to supplies. On May 12, the White House agreed to lower tariff rates for China before it had announced trade deals with Europe, Canada, Japan, or other allied countries.

China produces 90 percent of the global supply of rare-earth magnets, which are not the only products that Beijing can deny the rest of the world. Decades of industrial policy and fierce entrepreneurialism have created the world’s mightiest manufacturing machine. Chinese firms are also dominant producers of many pharmaceutical ingredients (especially for antibiotics and ibuprofen), battery materials, and entire categories of electronics components—not to mention smartphones, household appliances, toys, and other finished goods that American consumers want.

In cutting off rare-earth magnets, officials in Beijing flexed but one finger. If they wanted, they could have strangled vital sectors of the American economy.

How did America lose so much productive capacity to China and end up in such a vulnerable position? Think about it this way: China is an engineering state, which treats construction projects and technological primacy as the solution to all of its problems, whereas the United States is a lawyerly society, obsessed with protecting wealth by making rules rather than producing material goods. Successive American administrations have attempted to counter Beijing through legalism—levying tariffs and designing an ever more exquisite sanctions regime—while the engineering state has created the future by physically building better cars, better-functioning cities, and bigger power plants.

Engineers have quite literally ruled modern China. As a corrective to the ideological mayhem of the Mao years, Deng Xiaoping promoted engineers to the top ranks of China’s government from the 1980s onward. By 2002, all nine members of the politburo’s standing committee—the apex of the Communist Party—had trained as engineers. Xi Jinping studied chemical engineering at Tsinghua University, China’s most prominent science institution. At the start of his third term, in 2022, Xi filled the politburo with executives who had experience in aerospace and weapons.

Huge bursts of construction define today’s China. A person born in 1993—when the country built its first modern expressway—was able, when she reached the legal driving age 18 years later, to motor across a network of highways that surpassed the length of America’s interstate system. As part of China’s economic transformation, officials in Beijing have directed the construction of high bridges, large dams, enormous power plants, and entire new cities. The corporate sector, abetted by government policies that encourage manufacturing, is fixated on production too. A rough rule of thumb is that China produces a third of the world’s manufacturing, including essential products such as structural steel and container ships.

Derek Thompson: The disturbing rise of MAGA Maoism

The United States, by contrast, has a government of the lawyers, by the lawyers, and for the lawyers. More than half of U.S. presidents practiced law at some point in their career. About half of current U.S. senators have a law degree. Only two American presidents worked as engineers: Herbert Hoover, who built a fortune in mining, and Jimmy Carter, who served as an engineering officer on a Navy submarine. (Hoover and Carter are remembered for many things, especially for their dismal political instincts that produced thumping electoral defeats.)

Lawyerly instincts suffused Joe Biden’s economic policy, which brushed aside the invisible hand in favor of performing surgery on the economy—a subsidy scheme for one corporation, an antitrust case against another. Biden hoped to reindustrialize America via landmark bills such as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, but his administration’s legalistic commitments repeatedly tripped up the pace of construction. Executive agencies were so obsessed with designing rules for how to do things that little ended up being built. Efforts to connect rural areas to broadband or create a network of electric-vehicle-charging stations barely broke ground before voters reelected Donald Trump.

Trump is not a lawyer, but he—like many wealthy Americans—is no stranger to using the courtroom to get what he wants. His business career and his presidency have been rife with lawsuits: against business partners, political opponents, news outlets, and sometimes his own lawyers. Trump’s governing style has a litigious air to it too: flinging accusations left and right, intimidating people into dropping their opposition, besmirching people in the court of public opinion. Where Biden was plodding and proceduralist, Trump is naturally inclined toward bare-knuckle lawfare.

The lawyerly society has some important advantages. You can’t build companies worth trillions without the rule of law to set up an environment where the rich feel safe to invest. The U.S. remains home to most of the world’s most valuable companies, in part because lawyers protect their right to profit off of their intellectual property. But the fact that wealthy companies and individuals can easily assert their interests in court is hardly a guarantee of broad economic progress for a society.