SteelCitySoldier

TSC Fantasy Football Champion 2016

An encyclopedia of stereotypes, from Virgil to Kamala to Mr. Fuji to the Mexicools, and many more in between

The following is an excerpt from David "The Masked Man" Shoemaker's new book, The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling. It has been slightly modified for this publication.

If you tuned in to the WWF on Saturday morning in the late '80s, or watched anepisode of Hulk Hogan's Rock 'n' Wrestling, it was hard not to notice the cultural and ethnic diversity the cast of brawlers represented. But despite the diversity, the characters' vocabulary wasn't exactly progressive. Though his English was faltering, Mr. Fuji threw around terms like "yard ape" and "lawn jockey" and "honky" in his prime. His protégé Don Muraco called Pedro Morales "a dirty Mexican pepper belly," and when it was suggested to him that Morales was actually Puerto Rican, he said, "Who cares? They're all the same." (He later attempted a more accurate bit of racism when he called Morales "a Puerto Rican hubcap thief.") He was one of a few wrestlers for whom "Mexican wetback" was a throwaway descriptor of Tito Santana. (Here he is calling Santana an "ignorant garbage picker.")

If the acts weren't always bald-facedly racist, their matches were often peppered with the patently offensive bad-guy shtick of legendary color commentator Jesse "The Body" Ventura. At various times Ventura reacted to a Junkyard Dog interview by saying JYD had "a mouth full of grits," called his rope-a-dope in-ring routine "a lot of shuckin' and jivin'." He commonly referred to fan favorite Santana as "Chico," dubbed his finishing move the "flying burrito" finisher, and, when Santana was getting pummeled atWrestleMania IV, Ventura said, "I betcha Chico wishes he was back selling tacos in Tijuana right now!" He similarly referred to black wrestler "Birdman" Koko B. Ware as "Buckwheat" until eventually Vince McMahon himself put a stop to it.

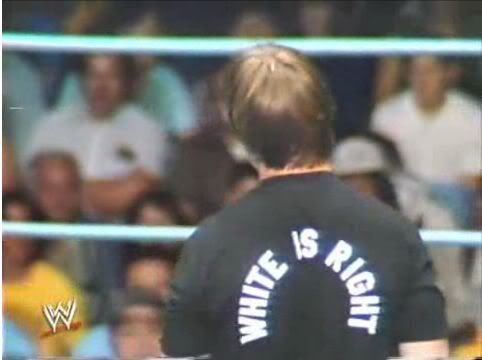

"Rowdy" Roddy Piper, a Canadian who was billed to be from Glasgow, Scotland, was a one-stop shop for racial insensitivity. He became a top-tier villain in California early in his career by insulting the region's Latino community. He once insisted on making amends by playing the Mexican national anthem on his bagpipes, but he played "La Cucaracha" instead. In the WWF, Piper exhibited a similar false apology when he invited Jimmy Snuka onto his "Piper's Pit" interview segment to apologize for Snuka not getting a chance to speak on his previous appearance. Piper decorated the set with pineapples and coconuts and eventually smashed a coconut over Snuka's head. (Piper's indiscretion didn't end there; he once talked soul food with Tony Atlas, said that Mr. T's lips looked "like acatcher's mitt," called T's fans "monkeys," mock-fed bananas to a poster of Mr. T, and told him that he would "whip him like a slave." At WrestleMania VI, he was wrestling Bad News Brown, who was presented as a black street thug but who was actually half black; Piper — who, it should be said, was the good guy in this feud — came to the ring with his body painted half black, down the middle.) Piper's racist grunts may have been part of a larger heel character, but it's likewise a part of a broader history of villains gleefully playing up racist tropes to get easy boos from the crowd. There were virulent racist personas like Colonel DeBeers, the AWA heel known for his pro-apartheid politics, and John Bradshaw Layfield, the conservative Texan in the WWE who briefly railed against illegal Mexican immigrants. Michael "P.S." Hayes, ringleader of the Fabulous Freebirds, often resorted to race-baiting to intensify feuds: The Freebirds' feud with Junkyard Dog turned on Hayes calling JYD "boy," and the Freebirds once came to the ring in a major match against the Road Warriors at Comiskey Park with the rebel flag painted on their faces. In 2008, Hayes was suspended from his backstage duties with WWE for supposedly telling African American wrestler Mark Henry, "I'm more of a ****** than you are." He was said to have used the N-word casually over the years without causing a stir. He is also credited with the notion that black wrestlers don't need gimmicks because being black is their gimmick.

With the exception of The Junkyard Dog,1 whose dog collar, chains, and postmatch shuck-and-jive routine were almost fully subsumed in the triumphant magnetism of his persona, perhaps no gimmick is as renowned — or as straightforward — as "The Ugandan Headhunter" Kamala, a ridiculous tribal boogeyman from "Deepest, Darkest Africa," who was created by Jerry "the King" Lawler based on a reductive Frank Frazetta illustration. (So yes, it's fair to call Kamala a stereotype of a stereotype.) His mannerisms and grunts were inhuman, and his cannibalism was a calling card, and with his face- and chest-paint, his leopard-print loincloth, and his spear, Kamala was such a sensation that he headlined every major promotion during the '80s and '90s. He often appeared alongside his "handler," Kim Chee, who wore a pith helmet and tan wrestlers mask. Any offense tendered by Chee was lost in the voluminous shadow of denigration Kamala cast.

When you consider the recent history of African American wrestlers in pro wrestling, to simplify a performer's character to his race isn't as offensive as what's come when promoters try to give black wrestlers personas with more, shall we say, idiosyncrasy. In 1987, a small-time wrestler once known as "Soul Train" Jones in Memphis was introduced to the world as the "Million Dollar Man" Ted DiBiase's bodyguard-cum-manservant, Virgil. (In their debut video, he says he owns Virgil, and Virgil responds "Yessuh!") Over the years, DiBiase bought the services and the souls of numerous wrestlers, but Virgil wasn't just a sellout; he was a slave, almost unabashedly. His name, purportedly coined by Bobby "The Brain" Heenan, was a subtle jab at NWA showrunner and star Dusty Rhodes, born Virgil Runnels, who was known for "acting black" in speech and mannerism. Similarly, in 1988, a famous villain named the One Man Gang, who sported a mohawk and denim vest and generally looked and acted like a monstrous Hells Angel, was repackaged with minimal explanation as Akeem the African Dream, a white man of African descent who dressed in a dashiki and spoke in jive while sluicing his forearms through the air like a '70s-movie pimp. This character too was supposed to be a joke aimed at Rhodes, who counts semiforgotten African American Sweet Daddy Siki among his greatest influences (Siki's bleached-blond hair, "Siki strut," and verbal style are direct precursors of Rhodes's affect). Rhodes was raised in poverty in Texas and pegged his accent more on socioeconomics than race, but he was nonetheless the subject of racially charged ribbing, though, as with Virgil, targeting Rhodes was more a general shot across the bow at the Crockett promotion than anything. Anyway, Akeem (whose real name was George Gray) suddenly was announced as being from "Deepest, Darkest Africa" and was speaking in a parody of a parody of a "black accent." Managed by Slick — who was known as both the "Jive Soul Bro" and the "Doctor of Style," dressed in polyester suits and pageboy hats, and later became, in real life and exploited on-screen, a reverend — the duo seemed to embody every sketchy African American stereotype in one middling act.

The following is an excerpt from David "The Masked Man" Shoemaker's new book, The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling. It has been slightly modified for this publication.

If you tuned in to the WWF on Saturday morning in the late '80s, or watched anepisode of Hulk Hogan's Rock 'n' Wrestling, it was hard not to notice the cultural and ethnic diversity the cast of brawlers represented. But despite the diversity, the characters' vocabulary wasn't exactly progressive. Though his English was faltering, Mr. Fuji threw around terms like "yard ape" and "lawn jockey" and "honky" in his prime. His protégé Don Muraco called Pedro Morales "a dirty Mexican pepper belly," and when it was suggested to him that Morales was actually Puerto Rican, he said, "Who cares? They're all the same." (He later attempted a more accurate bit of racism when he called Morales "a Puerto Rican hubcap thief.") He was one of a few wrestlers for whom "Mexican wetback" was a throwaway descriptor of Tito Santana. (Here he is calling Santana an "ignorant garbage picker.")

If the acts weren't always bald-facedly racist, their matches were often peppered with the patently offensive bad-guy shtick of legendary color commentator Jesse "The Body" Ventura. At various times Ventura reacted to a Junkyard Dog interview by saying JYD had "a mouth full of grits," called his rope-a-dope in-ring routine "a lot of shuckin' and jivin'." He commonly referred to fan favorite Santana as "Chico," dubbed his finishing move the "flying burrito" finisher, and, when Santana was getting pummeled atWrestleMania IV, Ventura said, "I betcha Chico wishes he was back selling tacos in Tijuana right now!" He similarly referred to black wrestler "Birdman" Koko B. Ware as "Buckwheat" until eventually Vince McMahon himself put a stop to it.

"Rowdy" Roddy Piper, a Canadian who was billed to be from Glasgow, Scotland, was a one-stop shop for racial insensitivity. He became a top-tier villain in California early in his career by insulting the region's Latino community. He once insisted on making amends by playing the Mexican national anthem on his bagpipes, but he played "La Cucaracha" instead. In the WWF, Piper exhibited a similar false apology when he invited Jimmy Snuka onto his "Piper's Pit" interview segment to apologize for Snuka not getting a chance to speak on his previous appearance. Piper decorated the set with pineapples and coconuts and eventually smashed a coconut over Snuka's head. (Piper's indiscretion didn't end there; he once talked soul food with Tony Atlas, said that Mr. T's lips looked "like acatcher's mitt," called T's fans "monkeys," mock-fed bananas to a poster of Mr. T, and told him that he would "whip him like a slave." At WrestleMania VI, he was wrestling Bad News Brown, who was presented as a black street thug but who was actually half black; Piper — who, it should be said, was the good guy in this feud — came to the ring with his body painted half black, down the middle.) Piper's racist grunts may have been part of a larger heel character, but it's likewise a part of a broader history of villains gleefully playing up racist tropes to get easy boos from the crowd. There were virulent racist personas like Colonel DeBeers, the AWA heel known for his pro-apartheid politics, and John Bradshaw Layfield, the conservative Texan in the WWE who briefly railed against illegal Mexican immigrants. Michael "P.S." Hayes, ringleader of the Fabulous Freebirds, often resorted to race-baiting to intensify feuds: The Freebirds' feud with Junkyard Dog turned on Hayes calling JYD "boy," and the Freebirds once came to the ring in a major match against the Road Warriors at Comiskey Park with the rebel flag painted on their faces. In 2008, Hayes was suspended from his backstage duties with WWE for supposedly telling African American wrestler Mark Henry, "I'm more of a ****** than you are." He was said to have used the N-word casually over the years without causing a stir. He is also credited with the notion that black wrestlers don't need gimmicks because being black is their gimmick.

With the exception of The Junkyard Dog,1 whose dog collar, chains, and postmatch shuck-and-jive routine were almost fully subsumed in the triumphant magnetism of his persona, perhaps no gimmick is as renowned — or as straightforward — as "The Ugandan Headhunter" Kamala, a ridiculous tribal boogeyman from "Deepest, Darkest Africa," who was created by Jerry "the King" Lawler based on a reductive Frank Frazetta illustration. (So yes, it's fair to call Kamala a stereotype of a stereotype.) His mannerisms and grunts were inhuman, and his cannibalism was a calling card, and with his face- and chest-paint, his leopard-print loincloth, and his spear, Kamala was such a sensation that he headlined every major promotion during the '80s and '90s. He often appeared alongside his "handler," Kim Chee, who wore a pith helmet and tan wrestlers mask. Any offense tendered by Chee was lost in the voluminous shadow of denigration Kamala cast.

When you consider the recent history of African American wrestlers in pro wrestling, to simplify a performer's character to his race isn't as offensive as what's come when promoters try to give black wrestlers personas with more, shall we say, idiosyncrasy. In 1987, a small-time wrestler once known as "Soul Train" Jones in Memphis was introduced to the world as the "Million Dollar Man" Ted DiBiase's bodyguard-cum-manservant, Virgil. (In their debut video, he says he owns Virgil, and Virgil responds "Yessuh!") Over the years, DiBiase bought the services and the souls of numerous wrestlers, but Virgil wasn't just a sellout; he was a slave, almost unabashedly. His name, purportedly coined by Bobby "The Brain" Heenan, was a subtle jab at NWA showrunner and star Dusty Rhodes, born Virgil Runnels, who was known for "acting black" in speech and mannerism. Similarly, in 1988, a famous villain named the One Man Gang, who sported a mohawk and denim vest and generally looked and acted like a monstrous Hells Angel, was repackaged with minimal explanation as Akeem the African Dream, a white man of African descent who dressed in a dashiki and spoke in jive while sluicing his forearms through the air like a '70s-movie pimp. This character too was supposed to be a joke aimed at Rhodes, who counts semiforgotten African American Sweet Daddy Siki among his greatest influences (Siki's bleached-blond hair, "Siki strut," and verbal style are direct precursors of Rhodes's affect). Rhodes was raised in poverty in Texas and pegged his accent more on socioeconomics than race, but he was nonetheless the subject of racially charged ribbing, though, as with Virgil, targeting Rhodes was more a general shot across the bow at the Crockett promotion than anything. Anyway, Akeem (whose real name was George Gray) suddenly was announced as being from "Deepest, Darkest Africa" and was speaking in a parody of a parody of a "black accent." Managed by Slick — who was known as both the "Jive Soul Bro" and the "Doctor of Style," dressed in polyester suits and pageboy hats, and later became, in real life and exploited on-screen, a reverend — the duo seemed to embody every sketchy African American stereotype in one middling act.