You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

African American Architects

- Thread starter Asicz

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?IllmaticDelta

Veteran

repost of mine from the afram thread

Clarence Wesley "Cap" Wigington (1883-1967) was an African-American architect who grew up in Omaha, Nebraska. After winning three first prizes in charcoal, pencil, and pen and ink at an art competition during the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in 1899, Wigington went on to become a renowned architect across the Midwestern United States, at a time when African-American architects were few.[1] Wigington was the nation's first black municipal architect,[2] serving 34 years as senior designer for the City of Saint Paul, Minnesota's architectural office when the city had an ambitious building program.[3] Sixty of his buildings still stand in St. Paul, with several recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. Wigington's architectural legacy is one of the most significant bodies of work by an African-American architect.[4]

Clarence Wesley Wigington was born in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1883, but his family soon moved to Omaha, where he was raised in North Omaha's Walnut Hill neighborhood. After graduating from Omaha High School at the age of 15[citation needed], Wigington left an Omaha art school in 1902 to work for Thomas R. Kimball, then president of the American Institute of Architects. After six years he started his own office. In 1910 Wigington was listed by the U.S. Census as one of only 59 African-American architects, artists and draftsmen in the country.[4] While in Omaha, Wigington designed the Broomfield Rowhouse, Zion Baptist Church, and the second St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church building, along with several other single and multiple family dwellings.[5]

After marrying Viola Williams, Wigington received his first public commission, to design a small brick potato chip factory in Sheridan, Wyoming. He ran the establishment for several years.[6]

It was in Saint Paul, Minnesota where Wigington created a national reputation. He moved there in 1914 and by 1917 was promoted to the position of senior architectural designer for the City of St. Paul. During the 1920s and '30s, Wigington designed most of the Saint Paul Public Schools buildings, as well as golf clubhouses, fire stations, park buildings, airports for the city. Other Wigington structures include the Highland Park Tower, the Holman Field Administration Building and the Harriet Island Pavilion, all now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, as well as the Roy Wilkins Auditorium. Wigington also designed monumental ice palaces for the St. Paul Winter Carnival in the 1930s and '40s.[7]

Wigington was among the 13 founders of the Sterling Club, a social club for railroad porters, bellboys, waiters, drivers and other black men. He founded the Home Guards of Minnesota, an all-black militia established in 1918 when racial segregation prohibited his entry into the Minnesota National Guard during World War I. As the leader of that group, he was given the rank of captain, from which the nickname "Cap" was derived.[8]

After retiring from the City of St. Paul in 1949, Wigington began a private architectural practice in California. Soon after moving to Kansas City, Missouri in 1967, he died on July 7.[9]

Notable designs

As senior architect for the city, Wigington designed schools, fire stations, park structures and municipal buildings. Aside from his work in Omaha, Wigington also designed the building which originally hosted the North Carolina State University at Durham.[10]

Nearly 60 Wigington-designed buildings still stand in St. Paul. They include the notable Highland Park Clubhouse, Cleveland High School, Randolph Heights Elementary School, and the downtown St. Paul Police Station, in addition to the Palm House and the Zoological Building at the Como Park Zoo.[11]

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Paul Revere Williams

, FAIA (February 18, 1894 – January 23, 1980) was an American architect based in Los Angeles, California. He practiced largely in Southern California and designed the homes of numerous celebrities, including Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Lon Chaney, Barbara Stanwyck and Charles Correll. He also designed many public and private buildings.[1][2]

A Trailblazing Black Architect Who Helped Shape L.A.

Paul Revere Williams began designing homes and commercial buildings in the early 1920s. By the time he died in 1980, he had created some 2,500 buildings, most of them in and around Los Angeles, but also around the globe. And he did it as a pioneer: Paul Williams was African-American. He was the first black architect to become a member of the American Institute of Architects in 1923, and in 1957 he was inducted as the AIA's first black fellow.

His granddaughter, Karen E. Hudson, has been chronicling Williams' life and work for the past two decades. Her latest book, Paul R. Williams: Classic Hollywood Style, focuses on some of the homes of his celebrity clients. They feature many characteristics that were innovative when he used them in the 1920s through the '70s and are considered common practice now — like the patio as an extension of the house, and hidden, retractable screens.

When Paul Williams began his career, he could find no black architects to be his role models or mentors. Born in downtown Los Angeles in 1894, Williams became orphaned before he turned 4 when his parents, Chester and Lila, died of tuberculosis. A family friend raised him and told him he was so bright, he could do anything he wanted. And what he wanted was to design homes for families — perhaps because he lost his own so early in his life. Despite warnings from those who thought he was being impractical ("Your own people can't afford you, and white clients won't hire you," was one such warning), Williams became an architect.

Architect Paul Williams (in a photo thought to be from the 1940s or '50s) developed the ability to sketch buildings upside down to accommodate white clients who might not want to sit next to him.

His work has come to signify glamorous Southern California to the rest of the country — and to the world. One of his hallmarks — a luxuriantly curving staircase — has captivated many a potential owner. Retired financial services magnate Peter Mullin remembers how he felt when he saw his 1925 Colonial, the first one Williams built in L.A.'s posh Brentwood neighborhood.

"The first time I saw it, I didn't think I could afford the house, but if I could afford the staircase, I wanted to take it with me!" Mullin laughs. He bought the house — once inhabited by producer Ingwald Preminger, brother of director Otto — and has enjoyed it for 35 years.

"Every now and then, I think about leaving," Mullin admits. "Then I look around ... and I can't. I just love this place."

That sentiment may explain why Williams' homes don't come on the market very often.

Bret Parsons is head of the architectural division of John Aaroe Group, a Beverly Hills real estate brokerage handling multimillion-dollar properties. He says when Williams homes come up for sale, real estate agents scramble to get the listing. "They're gobbled up in seconds," he says. "They're an absolute pedigree for someone to have in their arsenal."

Parsons says Williams homes posses grace, design and elegant proportions, which attracted people with money and taste.

Several of them were celebrities from Hollywood's heyday. Williams built an elegant bachelor pad for Frank Sinatra when the singer was between marriages. Lucille Ball and husband Desi Arnaz were clients. So was Cary Grant. Danny Thomas was both client and friend — Williams designed St. Jude Children's Hospital in Memphis gratis, as a favor to Thomas (and made Thomas promise not to tell, so he wasn't deluged with similar requests). In recent years, Denzel Washington, Ellen DeGeneres and Andy Garcia all have lived in Williams homes.

At the Beverly Hills Hotel, Williams designed the iconic Polo Lounge, the Crescent Wing and the Pink Palace's signature loopy signage. He also chose the colors — pink and green — that would signify the ultimate in service to its pampered guests for a century.

Paul R. Williams, in full Paul Revere Williams (born February 18, 1894, Los Angeles, California, U.S.—died January 23, 1980, Los Angeles), American architect noted for his mastery of a variety of styles and building types and for his influence on the architectural landscape of southern California. In more than 3,000 buildings over the course of five decades, mostly in and around Los Angeles, he introduced a sense of casual elegance that came to define the region’s architecture. His work became so popular with Hollywood royalty that he was known as the “architect to the stars.”

Paul R. Williams | American architect

Architecture of Paul Revere Williams, born 120 years ago, still 'remarkable'

T

his year marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of L.A. architect Paul Revere Williams. If you don't recognize the name, you know the work: The spider-like LAX Theme Building, Saks Fifth Avenue in Beverly Hills and significant parts of the Beverly Hills Hotel, including the Polo Lounge, are but a few of the 3,000 buildings Williams produced in his prolific 50-year career.

Williams was known as the architect to the stars in the 1930s, '40s and '50s, designing some of the grandest houses in town in an array of revival styles. His mastery of so many idioms and his willingness to give clients the look they wanted set him apart from L.A.'s Midcentury Modernists. But each Williams house bears his unique stamp of gentility: opulence with restraint, sophistication and warmth.

"His sense of scale and proportion is remarkable," says architectural historian Eleanor Schrader, who has spoken often in support of granting historic status to Williams houses. "There are always these beautiful sweeping staircases in the entry, and then every other room is so livable, the flow from room to room is wonderful. Everything is meant to fit together. That's why it is such a tragedy when any of these are lost or remodeled beyond what he would have envisioned."

At the moment, in fact, preservationists and neighbors are battling new owners bucking to demolish two Williams creations, one on Brentwood's Oakmont Drive and one on Beverly Hills' Mountain Drive, to build grander structures. With his houses in great demand now and their prices shooting up, Williams and his architectural gifts are firmly in the spotlight.

Architecture of Paul Revere Williams, born 120 years ago, still 'remarkable'

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Julian Francis Abele

(April 30, 1881 – April 23, 1950) was a prominent African-American architect, and chief designer in the offices of Horace Trumbauer. He contributed to the design of more than 400 buildings, including the Widener Memorial Library at Harvard University (1912–15), the Central Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia (1918–27), and the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1914–28). He was the primary designer of the west campus of Duke University (1924–54).[4]

Legacy

- The Allen Administration Building at Duke University, which he designed, was completed after his death in 1950.

- In 1988 Duke University honored Abele with his portrait that is displayed in the main lobby of the Allen Building. It was the first portrait of an African-American to be displayed on the campus.[14] To prominently acknowledge his contribution to Duke University's West Campus, the main quad at Duke is now officially named Abele Quad with a dedication plaque prominently placed at the busiest spot on campus.[13]

- On August 17, 2012, construction began on Julian Abele Park, at 22nd & Carpenter Streets in Philadelphia.[15][16]

- Architectural historian Dreck Spurlock Wilson is preparing the first biography of Abele.[17]

Meet the Black Architect Who Designed Duke University 37 Years Before He Could Have Attended It

Drawing of Duke University campus courtesy of UPenn

In 1902, when Julian F. Abele graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a degree in architecture, he was the school's first-ever black graduate. The debonair Philadelphia-born architect went on to design hundreds of elegant public institutions, Gilded Age mansions, and huge swathes of a prestigious then-whites-only university's campus. Yet the fact that an African-American architect worked on so many significant Beaux Arts-inspired buildings along the East Coast was virtually unknown until a political protest at Duke, the very university whose gracious campus he largely designed, was held in 1986.

Abele's contributions were not exactly hidden—during that era it was not customary to sign one's own designs— but neither were they publicized. When he died in 1950, after more than four decades as the chief designer at the prolific Philadelphia-based firm of Horace Trumbauer, very few people outside of local architectural circles were familiar with his name or his work. In 1942, when the long-practicing architect finally gained entry to the American Institute of Architects, the director of Philadelphia's Museum of Art, a building which Abele helped conceive in a classical Greek style, called him "one of the most sensitive designers anywhere in America."

The protests at Duke that ended up reviving his reputation had nothing to do with Abele's undeserved obscurity; they were protests against the racist regime in apartheid South Africa. Duke students were infuriated by the school's investments in the country, and built shanties in front of the university's winsome stone chapel, which was modeled after England's Canterbury Cathedral. One student (perhaps majoring in missing the point) wrote an editorial for the college paper complaining about the shacks, which she said violated "our rights as students to a beautiful campus."

Unbeknownst to even the university's administrators, Julian F. Abele's great-grandniece was a sophomore at the college in Durham, North Carolina. Knowing full well that her relative had designed the institution's neo-Gothic west campus and unified its Georgian east campus, Susan Cook wrote into the student newspaper contending that Abele would have supported the divestment rally in front of his beautiful chapel. Her great grand-uncle, who in addition to the chapel designed Duke's library, football stadium, gym, medical school, religion school, hospital, and faculty houses, "was a victim of apartheid in this country" yet the university itself was an example "of what a black man can create given the opportunity," she wrote. Cook asserted that Abele had created their splendid campus, but had never set foot on it due to the Jim Crow laws of the segregated South.

This was the first time that Abele's role in designing Duke, a whites-only university until 1961, had been acknowledged so publicly. Many school administrators were hearing about him for the very first time. Cook's claim that Abele had never even seen his masterwork up close was devastating. (Accounts differ, however. In 1989, Abele's closest friend from UPenn, the Hungarian Jewish architect Louis Magaziner, recalled being told by Abele that a Durham hotel had refused him a room when he was visiting the university. A prominent local businessman also remembered Abele coming to town).

Either way, the fact that by the 1980s most people had never even heard of the history-making architect, who designed an estimated 250 buildings while working at the well-known Trumbauer firm, including Harvard University's Widener Memorial library and Philadelphia's Free Library, was even more shocking. Cook's letter led to something of a reckoning. Today, there's a portrait of Abele hanging up at Duke, and the university is currently celebrating the 75th anniversary of the basketball arena he designed, the Cameron Indoor Stadium, which opened this week in 1940.

Raised in Philadelphia as the youngest of eight children of an accomplished family, Abele had excelled in school since early childhood, once winning $15 for his mathematical prowess. But Abele's years at UPenn—first as an undergraduate and then as the school's first black architecture student—took place in a climate that, while not as restrictive as the Jim Crow South, was still very racist. In addition to segregated seating in theaters and on transport, most campus gathering spots and sports teams were closed to African-Americans, and the dining hall and nearby restaurants refused to serve them.

It was an isolating atmosphere, and friendships could be hard to come by. "You spoke perfect English but no one spoke to you," wrote a woman of color who graduated from UPenn nearly two decades after Abele did. Yet, during his senior year at the university, Abele was elected president of the school's Architectural Society, and he also won student awards for his designs for a post office and a botany museum. His professors evidently thought highly of him: five years after Abele graduated, the head of the school's architecture program tried to lure him away from his firm for a job in California.

Abele's employer at that time, Horace Trumbauer, refused to let him go. He had become invaluable. Trumbauer had hired Abele in 1906 to be the assistant to the Philadelphia firm's chief designer, Frank Seeburger. When Seeburger departed in 1909, Abele ascended to his position. The young architect worked well with Trumbauer, who was self-conscious about his own lack of formal education—he learned the craft of architecture through apprenticeships and avid reading—and who built his firm by hiring very competent underlings.

Abele, a serious man who dressed in impeccable suits, spoke French fluently, and reveled in classical music, was exactly the technically gifted architect, proficient in Beaux Arts building styles, that Trumbauer needed for his team. "I, of course, would not want to lose Mr. Abele," Trumbauer brusquely replied when he was asked, in 1907, to release Abele from his contract. Many accounts describe the firm's artistic vision as Abele's, although dealing with clients and bringing in commissions fell to Trumbauer.

One such client was James Buchanan Duke, the tobacco millionaire who commissioned the Trumbauer firm to design vast residences in New York City and in Somerville, New Jersey for his family (and their 14 servants). The white-marble mansion in Manhattan was modeled on a 17th-century French château, and when it was completed in 1912, the New York Times declared it the "costliest home" on Fifth Avenue. By 1924, the Trumbauer firm was hired to transform and expand an existing college in Durham, North Carolina into a well-endowed university named after its patron.

Abele would spend the next two decades creating a magisterial campus for a university that he was not even allowed to attend. All his creations were done under the name of the firm. "The lines are all Mr. Trumbauer's," Abele once said. "But the shadows are all mine." But after his boss died of cirrhosis in 1938, the talented architect signed his name to one of his own designs for the very first time. It was for Duke's chapel, the same structure that played a part in reviving his reputation 48 years later.

Meet the Black Architect Who Designed Duke University 37 Years Before He Could Have Attended It

newworldafro

DeeperThanRapBiggerThanHH

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Horace King (1807-1885)

was an American architect, engineer, and bridge builder.[1] King is considered the most respected bridge builder of the 19th century Deep South, constructing dozens of bridges in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.[2] "In 1807, King was born into slavery on a South Carolina plantation. A slave trader sold him to a man who saw something special in Horace King. His owner, John Godwin taught King to read and write as well as how to build at a time when it was illegal to teach slaves. King worked hard and despite bondage, racial prejudice and a multitude of obstacles, King focused his life on working hard and being a genuinely good man. King built bridges, warehouses, homes, churches, and most importantly, he bridged the depths of racism. Ultimately, dignity, respect and freedom were his rewards, as he transcended the color lines inherent in the Old South of the nineteenth century. Horace King became a highly accomplished Master Builder and he emerged from the Civil War as a legislator in the State of Alabama. Affectionately known as Horace “The Bridge Builder” King and the "Prince of Bridge Builders," he also served his community in many important civic capacities." [3].

docu

Captain Crunch

Veteran

Didn’t know we designed LAX and Duke.

So not only did we build this country during slavery, we continued to make additions to it after slavery.

So not only did we build this country during slavery, we continued to make additions to it after slavery.

Pops is a black architect today

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Didn’t know we designed LAX and Duke.

So not only did we build this country during slavery, we continued to make additions to it after slavery.

slaves (many were skilled carpenters, bricklayers, stonemasons) played a huge role in building the white house

National Archives to Display Pay Stubs of Slaves Used to Build U.S. Capitol and White House

Didn’t know we designed LAX and Duke.

So not only did we build this country during slavery, we continued to make additions to it after slavery.

We were enslaved for our knowledge and expertise, and they've been obscuring that fact so no one remembers it, especially us, ever since. Consider our innovations in the handful of areas we've been granted access to like food and music and imagine what juggernauts we'd be in all areas if white supremacy didn't exist.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

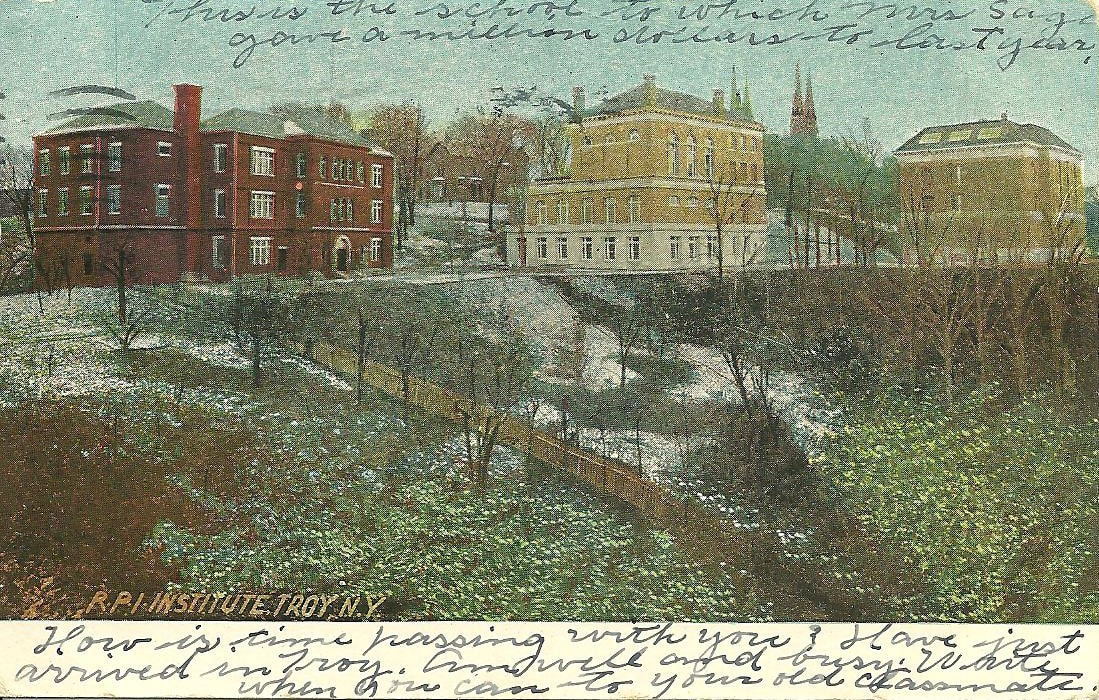

Garnet Douglass Baltimore (April 15, 1859 – June 12, 1946) was the first African-American engineer and graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, Class of 1881.[1][2]

He was named for two prominent abolitionists, Henry Highland Garnet and Frederick Douglass. He was known for his architectural, engineering, and landscaping work, including Prospect Park in Troy, and Forest Park Cemetery in Brunswick, New York.[3][4]

During his work on the extension of a lock on the Oswego Canal, Baltimore developed a system to test cement that was adopted as standard by the State of New York. He was an inductee of the Rensselaer Hall of Fame. Each year Rensselaer hosts the Garnet D. Baltimore Lecture Series in his honor.

In February 2005, former Troy mayor Harry Tutunjian ceremonially renamed the section of Eighth Street between Hoosick Street and Congress Street as Garnet Douglass Baltimore Street, "as a lasting tribute to a Trojan who gave so much to his community."

.

.

.

By the middle of the 19th century, Americans realized that parks provided a spot of nature and greenery amidst an increasingly busy and industrialized world. Many men, women and children worked six days a week, and never had the time or resources to get away. Yes, parks were beautiful, but they were also very important for mental and physical health. Cities that wanted to thrive began looking for space and funding for public parks.

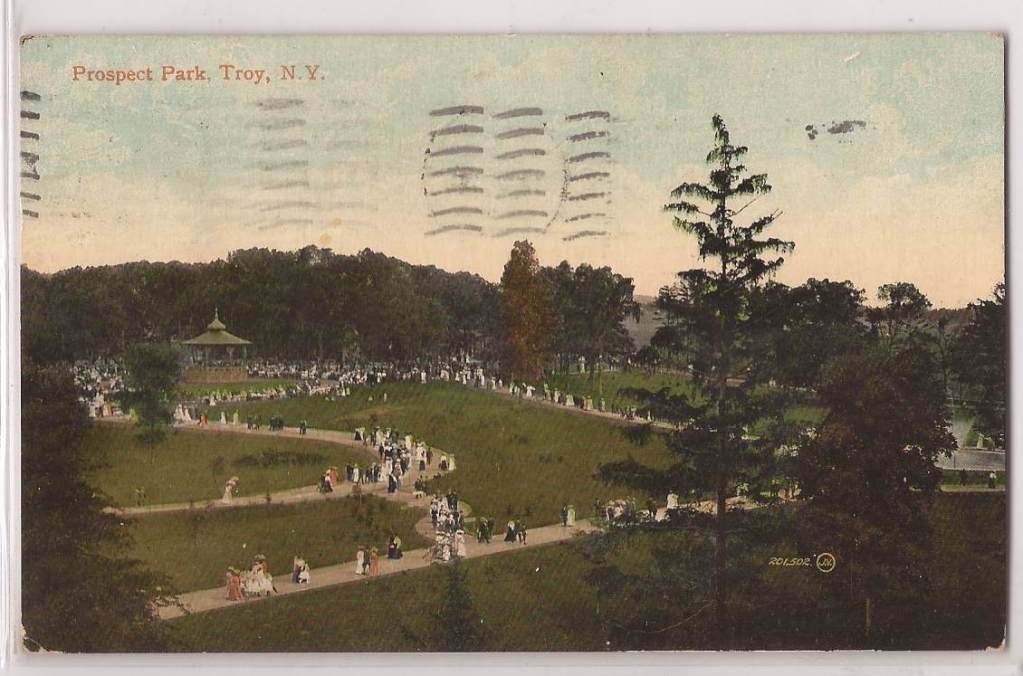

People from everywhere flocked to parks like Manhattan's Central Park and Brooklyn's Prospect Park. Postcards of the parks were circulated throughout the country as tourists marveled at the wonders. Many cities contemplating the development of their own parks came to see both, and many others to take notes. When the city of Troy decided to establish a new park on the top of what was called Warren Hill, one of the highest points in the city, they too looked downstate to Brooklyn for inspiration. Prospect Park gave the park’s designer some great ideas to incorporate in Troy’s own park. They also cribbed the name.

When Troy’s park first opened with a grand ceremony in 1902, they even invited dignitaries from New York City to come see it. Seth Low, one of Brooklyn’s leading citizens, and now the mayor of the newly established City of New York was invited, as well as the borough president of Brooklyn. Mr. Low had to bow out, however, and didn’t make the ceremony.

The park was still called Warren Park, however. The name wasn’t resonating with the public all that well, so the Troy newspapers decided to have a contest to rename the park. The most popular name chosen was Prospect Park. The name was approved by the Troy Common Council in 1902. It was very Brooklyn, and they knew it. Brooklyn got a kick out of it, and the Brooklyn Eagle quoted the Troy Press newspaper: “Prospect Park is admirable alliterative and beautifully Brooklynish” the paper announced.

As with its Brooklyn namesake, Troy opened Prospect Park long before it was finished. When the park had its opening ceremonies, almost all of the work in the park had yet to be done. The engineer /landscape architect chosen for the project was under tremendous pressure. The city had gone through a long bitter process just to obtain the land, so it had to be good. With all of the attention going to the new Prospect Park, Troy’s officials wanted the best man available for the job of planning and laying out this expensive and expansive plan. Fortunately, they had Garnet Douglass Baltimore on the job. He was a local RPI graduate, and a native son. He was also African American.

Garnet D. Baltimore was an inspiring man, and in many ways, the embodiment of the ideals of the city of Troy; a city that had nurtured the talents of a lot of very successful men and women. At the turn of the 20th century, Troy was at the height of its success, its fortunes made from metals, textiles, technology, education and commerce. To tell his story, we have to go back to the War of Independence, back to 1776.

During the Revolutionary War, a man named Samuel Baltimore was fighting for the nation’s freedom and also his own. He was a slave in Maryland, and his master had promised that if he fought as a soldier, he would be freed at war’s end. Baltimore took up the promise and fought long and hard. But his owner lied, and did not free him as promised. Samuel Baltimore didn’t wait, and took his own independence in hand and escaped up North soon afterward, and settled in the Hudson River town of Troy.

Troy had a small, but thriving black community. Slavery never really caught on in upstate New York, although the institution of slavery was legal until 1827, when it was finally and completely abolished. Most of New York State’s slaves were actually downstate in Brooklyn. The majority of black Trojans were either born into freedom, or like Samuel Baltimore, had escaped and made their way to this bustling river town where work was plentiful and slavery was not popular.

Samuel Baltimore settled in, got married and raised his family. His son, Peter F. Baltimore, became a successful barber in town, with a clientele that included many of Troy’s wealthiest and influential citizens. Peter Baltimore, like many Trojans, both black and white, was an ardent abolitionist. Troy was an important stop on the Underground Railroad, and one of the city’s most important abolitionists was the Reverend Henry Highland Garnet, the pastor of Troy’s Liberty Street Presbyterian Church. Like Samuel Baltimore, Garnet had taken his own independence from slavery in a remarkable story worthy of its own tale.

Peter Baltimore was a close confidant of Rev. Garnet, and was a friend of the great orator Frederick Douglass, as well. He named his son Garnet Douglass after both of them, welcoming his son into the world in 1859. The family was living at 162 Eighth Street at the time, near Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), in a house that would later fall victim to ham-handed mid-20th century urban renewal.

Growing up, young Garnet was influenced by his namesakes, as well as other influential African Americans such as mathematician Charles Reason and Underground Railroad leader Robert Purvis. Since she also had family in Troy, young Garnet probably also knew Harriet Tubman. Garnet’s father and Harriet Tubman were important players in the rescue of Charles Nalle, in one of the city’s proudest moments.

Garnet Baltimore was raised with high expectations, and he met them admirably. He was educated in Troy, and received a bachelor’s degree from RPI in 1881. He was the first African American to do so. He went on to receive a degree in Civil Engineering, and upon graduation was employed as an assistant engineer by a company building a bridge between the cities of Albany and Rensselaer. In 1883, he was in charge of a surveying party for the Granville and Rutland Railroad, a 56 mile line of track. He followed that project by being hired as an assistant engineer and surveyor on the nearby Erie Canal.

His career was not just in the Capital Region where he was known. Canal work became a specialty, and in 1884, Baltimore became head engineer in charge of building the Shinnacock and Peconic Canal in Southampton, on Long Island. The canal cuts across the South Fork of Long Island, near the Hamptons. From that project, he supervised the building of a lock on the Oswego Canal, in Western NY. That canal connected Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. The lock Baltimore was in charge of creating was a notoriously difficult one, in extremely muddy ground. It is still called the Mudlock today.

Returning to Troy, Garnet Baltimore took his skills to the land. He became a landscape architect and engineer, designing Forest Park Cemetery on the outskirts of the city in Brunswick. The cemetery’s owners wanted to outdo Troy’s famous Oakwood Cemetery, a beautiful park cemetery, the final resting place of many of Troy’s leading citizens and famous folk, including “Uncle Sam” Wilson. Garnet designed the entrance to the cemetery, planned winding trails and groves, and a receiving tomb at the entrance. Unfortunately, the project went bankrupt, and it was never completed past that point. That too, is a story worth telling for another time.

With his reputation as a civic engineer quite secure, Garnet D. Baltimore was in the perfect position to be hired to design Troy’s new Prospect Park. This being Troy, the journey was fraught with politics, and the usual battles between visionaries and cheapskates, influential citizens and pundits.

cont------>Garnet Douglass Baltimore - Troy's Master of Landscape

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

So not only did we build this country during slavery, we continued to make additions to it after slavery.

MasterOfAllHeSurveyz

All Star

Dope thread.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

another one not mentioned in that article

Wallace Augustus Rayfield

W. A. Rayfield: Mt. Gilead Baptist Church

.

.

The Legacy Of Pioneering African-American Architect Wallace A. Rayfield | National Trust for Historic Preservation

Docu that's in the works on him

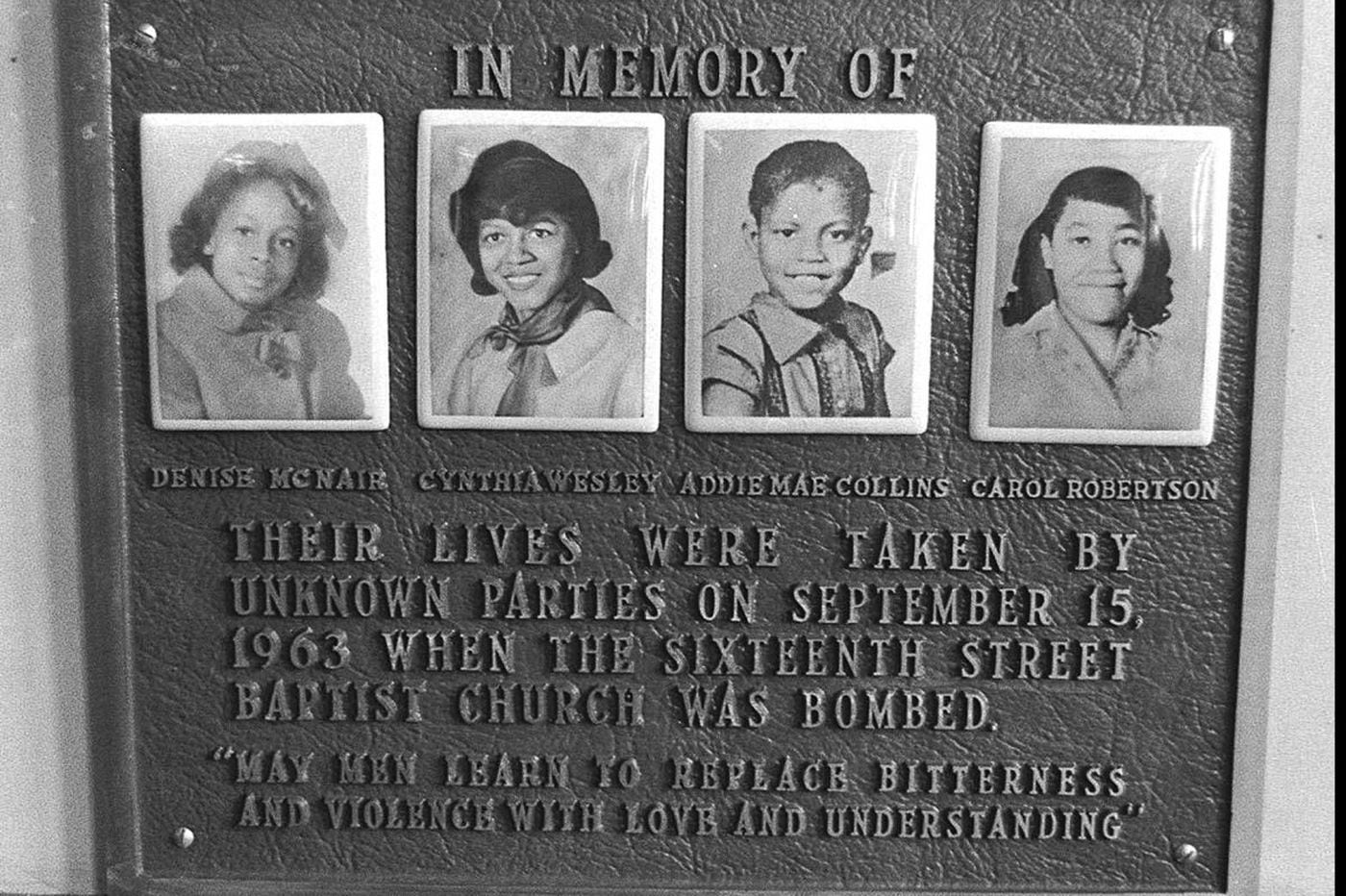

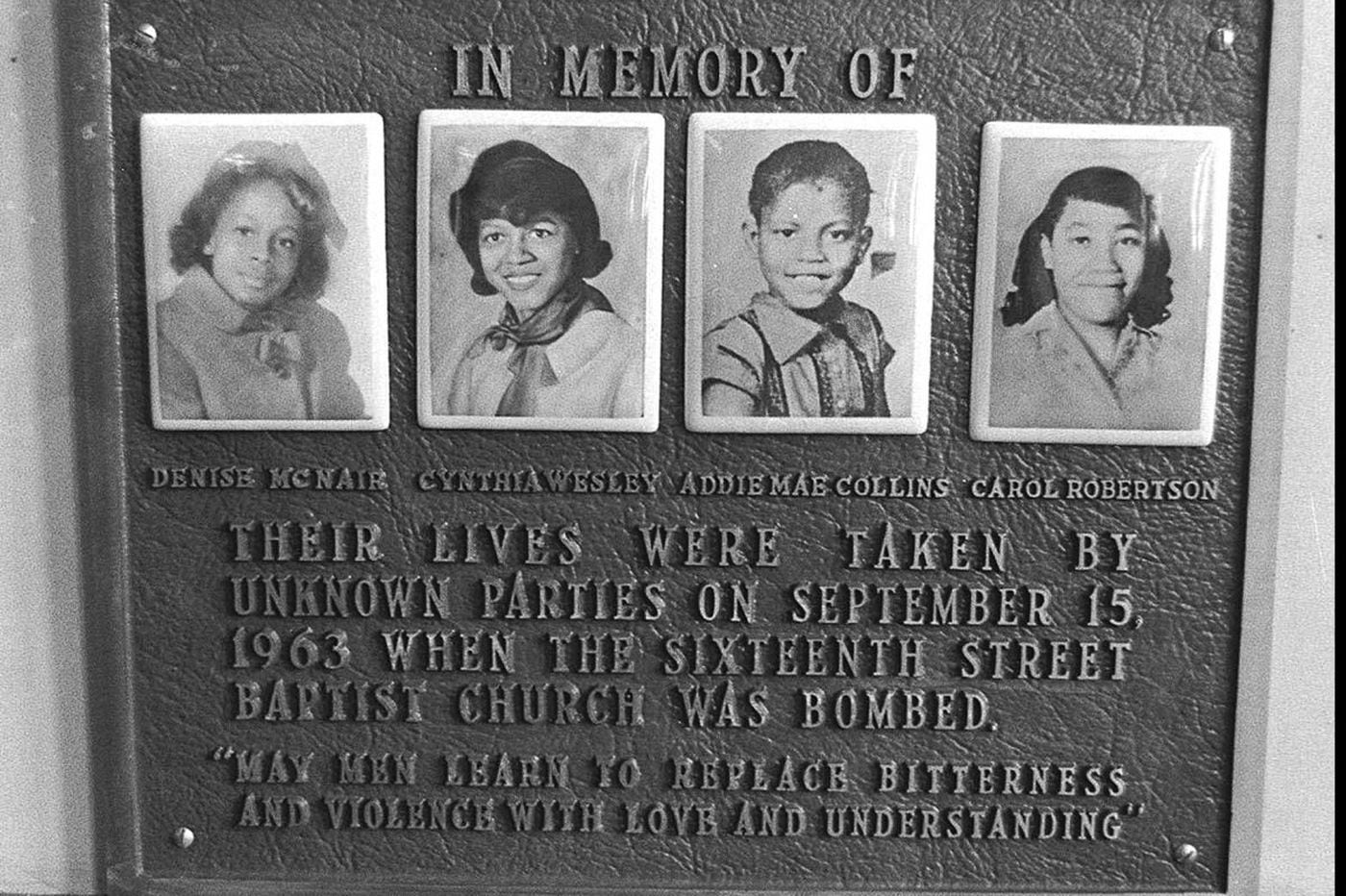

he designed/built the church that would be the place of the Birmingham bombings

Wallace Augustus Rayfield

(born Macon, Georgia around May 10, 1874 – February 28, 1941) was the second formally educated practicing African American architect in the United States.

Rayfield attended schools in Macon, Georgia before moving to Washington, DC after the death of his mother. He was an apprentice at an architectural firm while attending Howard University. He then completed a graduate certificate from Pratt Institute before earning his bachelor's degree in architecture from Columbia University in 1899.[1] Upon graduation, he was recruited by Booker T. Washington to the Directorship of the Architectural and Mechanical Drawing Department at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. In 1907, Rayfield opened a professional office in Tuskegee from which he sold mail-order plans nationwide. He also advertised "branch offices" in Birmingham, Montgomery, Mobile and Talladega, Alabama and Atlanta, Savannah, Macon and Augusta, Georgia.

He left Tuskegee Institute and moved to Birmingham in 1908 to focus on his young practice. He was elected as Superintending Architect for the Freedman's Aid Society and Connectional Architect of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.

He is credited with some 359 “known” buildings in 19 states, including 15 in Mississippi. Rayfield also designed the Trinity Building in South Africa. JRGordon took a look at the still-mysterious Herodon Baptist Church in Vicksburg also back in 2011.

One of those sort-of-south states in which he designed a church was Texas. (I mistakenly thought I was from the “south” until I moved to Mississippi, where I was promptly–and for the most part, politely–corrected). Rayfield is the architect of the Mount Gilead Baptist Church in downtown Fort Worth, Texas. Fort Worth is a little off the Mississippi beaten path of Suzassippi’s Mississippi road trips for the summer, but since it is a Rayfield building and he is well-connected with Mississippi, I hoped you would not mind the several hundred miles out of your way to get here.

Mount Gilead holds claim to being the “Mother” of all African American churches in Tarrant County, having been founded in 1875 as the first church of any denomination (fortworthtexas.gov/library). The congregation met in two other locations prior to erection of the building at the current site, just on the eastern edge of downtown Fort Worth. While at one time, it was about the first thing one saw driving into downtown from I-30, it actually took some effort to find it now.

The addition of the Amtrak station, and significant gentrification of the area, coupled with re-routing of roads, required several trial and error attempts to locate the building, although I still remembered where it was. The good news is that Fort Worth embarked on a plan to save historic downtown buildings several years ago, and many of their beautiful Art Deco styles from the 1920s boom, and earlier buildings from the 1800s, are alive and well. The bad news is that like most places, gentrification takes the housing of low income folks who were left in the inner city during the suburban flight, and poor and working class people are displaced out of the new loft and condo style living so favored in historic downtowns.

Wallace Augustus Rayfield left his mark from Texas to South Africa, and points in between. Echoing Malvaney’s call in 2011, keep an eye out for previously undocumented Rayfield buildings in your state or country–wherever you are.

W. A. Rayfield: Mt. Gilead Baptist Church

.

.

As an instructor of mechanical and architectural drawing at Tuskegee, Rayfield worked alongside Robert Taylor, the first black architect to graduate from MIT. Rayfield oversaw the expansion of the school’s mechanical drawing department from a cramped room with boards nailed atop sawhorses to a large, well-lit space with 47 drafting tables. Rayfield also made his first foray into printing with Industrial Drawing Book, a textbook meant to bring a degree of professionalism to the young school.

Rayfield’s skills as a printer were critical to his success as an architect. After leaving Tuskegee and opening his own architecture practice in Birmingham in 1908, Rayfield began designing and printing advertisements, newsletters, and plan books to reach a wider audience.

Among the plates Durough preserved are Rayfield-designed advertisements for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post. Some tout plans for bungalows, schools, and barns. One set features the headline “Going to Build a Church?” and offers free sample designs to anyone requesting them by mail. Rayfield used certain designs to appeal to Baptists and others for Christian Scientists, Catholics, and Lutherans. To appeal to white clients, he drew Caucasians in many of his ads

Rayfield’s efforts to build a practice paid off. He designed more than 400 buildings for clients in at least 20 states, including Illinois, Texas, and Maryland, and in Liberia. More than 130 of his structures were built in Birmingham alone. He became the superintending architect for the Freedmen’s Aid Society and chief architect of the A.M.E. Zion Churches of America.

He was also a community leader, supporting African-Americans through a marketing newsletter called The Colored Mechanics of Birmingham, in which he promoted the skills of local black contractors. Some of his residential projects became the first to be designed, financed, and built by blacks.

“He was an incredibly savvy businessman,” says University of Alabama historian Kari Fredrickson. “With entrepreneurial skill and through sheer determination, Rayfield had a profound impact on the southern landscape.”

So why isn’t he better remembered? One reason is that his practice collapsed during the Depression, when the unemployment rate in Birmingham was twice the national average. Another reason is race: Rayfield was one of few black architects working in Birmingham. The final reason may have been his sudden demise. In 1941, Rayfield suffered a stroke and died in his late 60s.

“So much of Rayfield’s material was destroyed,” says Daniel Ross, retired editor-in-chief of the University of Alabama Press. “All the things a working architect would have had on paper were either sold at a bankruptcy sale or lost. But from these plates, we can see what his business was really like.”

The most famous Rayfield building still stands. Completed in 1911, the 16th Street Baptist Church was the site of a 1963 bomb blast that killed four black teenage girls. It immediately became an icon for the civil rights struggle. Today, 16th Street Baptist has become a popular destination for tourists, and now is part of the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument.

“Though he was more educated and more accomplished than many white architects, he wasn’t given much attention,” says Durough, who is determined to make the Rayfield name—and his legacy as an architect of color—more widely known

The Legacy Of Pioneering African-American Architect Wallace A. Rayfield | National Trust for Historic Preservation

Docu that's in the works on him

he designed/built the church that would be the place of the Birmingham bombings

T'krm

Superstar

Literally! Just imagine the level skill, and architectural genius it took to construct sites like the W.H, and the Monticello ect. by slaves.Didn’t know we designed LAX and Duke.

So not only did we build this country during slavery, we continued to make additions to it after slavery.