ogc163

Superstar

Jered Snyder and Jen Zhao of Oakland got married in 2015. Asian American women are among the groups that are more likely to marry outside their race.

Photo: Paul Chinn, The Chronicle

The growth of interracial marriage in the 50 years since the Supreme Court legalized it across the nation has been steady, but stark disparities remain that influence who is getting hitched and who supports the nuptials, according to a major study released Thursday.

People who are younger, urban and college-educated are more likely to cross racial or ethnic lines on their trip to the altar, and those with liberal leanings are more apt to approve of the unions — trends that are playing out in the Bay Area, where about 1 in 4 newlyweds entered into such marriages in the first half of this decade.

Among the most striking findings was that black men are twice as likely to intermarry as black women — a gender split that reversed for Asian and Pacific Islander Americans and, to researchers, underscores the grip of deeply rooted societal stereotypes.

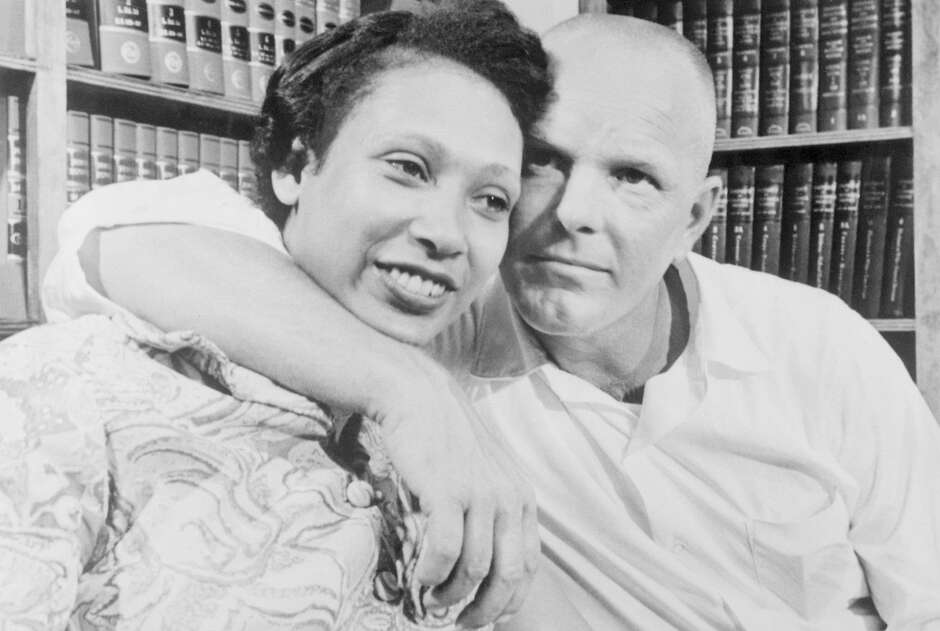

The Supreme Court ruled unanimously that a Virginia law banning marriage between African Americans and Caucasians was unconstitutional, thus nullifying similar statues in 15 other states. The decision came in a case involving Richard Perry Loving, a white construction worker and his African American wife, Mildred. The couple married in the District of Columbia in 1958 and were arrested upon their return to their native Caroline County, Virginia. They were given one year suspended sentences on condition that they stay out of the state for 25 years. The Lovings decided in 1963 to return home and fight banishment, with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Photo: Bettmann, Bettmann Archive

The comprehensive study was released by the Pew Research Center to mark a half-century since the nation’s high court, in Loving vs. Virginia, invalidated antimiscegenation laws that had remained in more than a dozen states. The study drew on data from Pew surveys, the U.S. census and the research group NORC at the University of Chicago.

Overall, roughly 17 percent of people who were in their first year of marriage in 2015 had crossed racial or ethnic lines, up from 3 percent in 1967. Across the country, 10 percent of all married couples — about 11 million people — were wed to someone of a different race or ethnicity as of 2015, with the most common pairing a Hispanic husband and a white wife.

While the Bay Area has among the highest rates of intermarriage in the country, a multiracial married couple remains a rare thing in some regions. On the low end of the spectrum is Jackson, Miss., where they account for just 3 percent of new marriages.

That ratio is hard to fathom for Oakland couple Jen Zhao and Jered Snyder, who got married two years ago. She is Asian American, he is white, and they don’t stand out in the local crowd, Zhao said.

“I’ve definitely noticed it,” she said, “like every other couple was an Asian-white couple.”

But their location in the Bay Area doesn’t mean they haven’t faced some backlash. Zhao and her husband have heard racially tinged comments about their relationship, including a stranger calling her a “gold digger.”

“I think there is that stereotype that a lot of Asian women are with white guys for money,” she said. Others have commented on her husband having “yellow fever.”

Yet for the most part, the couple’s circle of family and friends have been supportive, she said.

“I was a little worried at first,” she said. “But they have been very loving.”

Both changes in social norms and raw demographics have contributed to the increase in intermarriages, with Asians, Pacific Islanders and Hispanics — the groups most likely to marry someone of another race or ethnicity — making up a greater part of the U.S. population in recent decades, according to the report.

Meanwhile, public opinion has shifted toward acceptance, with the most dramatic change seen in the number of non-blacks who say they would oppose a close relative marrying a black person. In 2016, 14 percent of whites, Hispanics and Asian Americans polled said they would oppose such a marriage, down from 63 percent in 1990.

Rates of intermarriage vary in many ways — by race, age, gender, geography, political affiliation and education level. And the differences can be pronounced.

Among newlyweds, for example, 24 percent of African American men are marrying someone of a different race or ethnicity, compared with 12 percent of black women. While the overall intermarriage rates have increased for blacks of each gender, the gap between genders is “long-standing,” the Pew researchers said.

This gender disparity is reversed for Asian and Pacific Islanders, with 21 percent of recently married men in mixed unions, compared with 36 percent of women. Why such differences exist is not entirely understood.

“There’s no clear answer in my view,” said Jennifer Lee, a sociology professor at UC Irvine and an expert in immigration and race. “What I suspect is happening are Western ideals about what feminity is and what masculinity is.”

She noted that not all intermarriages are viewed equally — and never have been.

“We’re more likely to view Asian and Hispanic and white as intercultural marriages — they see themselves crossing a cultural barrier more so than a racial barrier,” she said. But a marriage between a black person and a white person crosses a racial color line, “a much more difficult line to cross.”

Notably, a recent Pew survey found that African Americans were more likely than whites or Hispanics to say that interracial marriage was generally a bad thing for society, with 18 percent expressing that view.

It can be seen as “leaving” the community, said Ericka Dennis of Foster City, who is black and has been married for 20 years to her husband, Mike, who is white.

She said that for years, they didn’t think much about being an interracial couple, save some backlash from her husband’s conservative Texas family. But in recent months, since the election of President Trump, thecouple have heard more open and aggressive comments, and seen more stares.

“I feel like now, we deal with so much more racism today,” she said. “Things are just so much more open, and people don’t hide their negativity as much. It’s a struggle.”

Despite the positive trends shown in the Pew report, she said fear remains. But with 20 years of marriage behind them, it’s easier to deal with, she said.

“We’ve been together so long,” she said, “that we don’t pay attention to other people’s bull—.”

The study found the rates of intermarriage and the acceptance of it can rise and fall with factors like geography and political inclination. In urban areas, for example, 18 percent of newlyweds married someone of a different race or ethnicity in recent years, compared with 11 percent outside of cities.

As intermarriage spreads, fault lines are exposed

they don't want us in their society why get married into their families if they are just gonna be racist a$$holes... They say one thing and do another... Things have not changed and are not getting better...

they don't want us in their society why get married into their families if they are just gonna be racist a$$holes... They say one thing and do another... Things have not changed and are not getting better... no matter what these swirlers say. they the first to go...

no matter what these swirlers say. they the first to go...