‘Caste is anti-Asian hate’: the activists fighting ‘less visible’ discrimination in the US

Thenmozhi Soundararajan has spent her life battling for equity. Now California could pass a landmark law protecting it

Claire Wang

Mon 17 Apr 2023 06.00 EDT

Thenmozhi Soundararajan calls the California bill the ‘culmination of a life’s work’. Photograph: The Washington Post/Getty Images

Thenmozhi Soundararajan has spent her life battling for equity. Now California could pass a landmark law protecting it

Thenmozhi Soundararajan had one of her earliest encounters with India’s ancient caste ladder when she was 10, during a playdate at a friend’s house not long after immigrating to the US.

When Soundararajan revealed that she belongs to a caste once known as “untouchables” – also known by the Sanskrit term “Dalit” – her friend’s mother, with a disgusted look, asked her to eat communal snacks on a separate plate so she could not taint the rest of the family.

“Caste is one of the most severe versions of anti-Asian hate,” said Soundararajan, now one of the US’s pre-eminent Dalit feminists, “but it’s not as visible because it’s hate amongst us.”

Soundararajan spent the following three decades advancing the civil rights of Dalits like herself and her parents, who fall at the bottom of the caste system, which is woven into many religions across south Asia. In the diaspora, it often leads to intra-community violence that can be hard for outsiders to understand. A multimedia storyteller and musician, Soudararajan has produced a documentary, a podcast and a new book, The Trauma of Caste, on caste oppression. In 2015, she founded the Oakland, California-based Equality Labs, the largest Dalit civil rights organization in the US, which conducted the first survey on caste discrimination in the US.

California, which has one of the largest south Asian populations in the country, has become ground zero for the caste equity movement.

In 2020, state regulators sued the technology company Cisco, alleging that two high-caste Indian managers had discriminated against a Dalit engineer by subjecting him to lower pay and inferior terms of employment. Last year, California State University became the first university system to add caste as a protected category to its anti-discrimination policy. And last month, California lawmakers introduced a new bill that would make the state the first in the nation to add caste as a protected category to its anti-discrimination laws. (In February, Seattle became the first US city to enshrine caste protections into its constitution.)

For Soundararajan, the legislation felt like a watershed moment for the caste equity movement that she helped build.

“It’s a culmination of a life’s work, both living under the trauma of caste and turning that pain into power,” she said. “I wish I could tell my younger self that it’s going to be OK.”

Caste in America

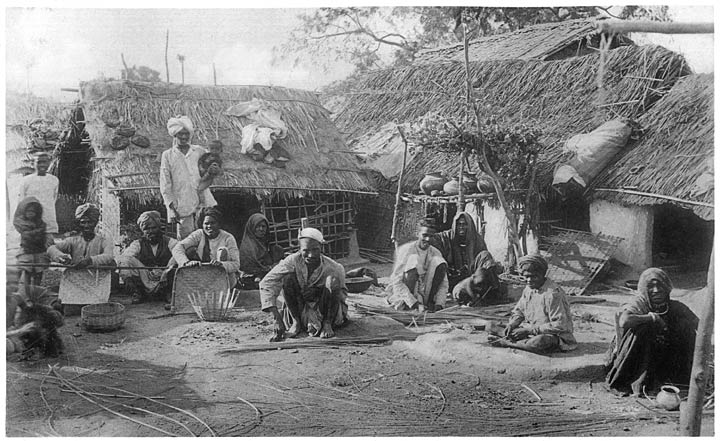

The Indian caste system, which dates back three thousand years, divides Hindus by birth into four categories that determine their place in society. Brahmins, members of the highest caste, have historically served as priests and teachers. Dalits, who fall outside of the caste system, work as street sweepers and toilet cleaners.According to the 2016 study by Equality Labs, which surveyed 1,500 south Asian Americans, two out of three Dalits in the US reported being mistreated by other south Asians at work because of their caste, one in four said they had endured verbal or physical assault, and one in three said they had experienced discrimination in school. The oppression they describe is wide-ranging, from slurs and sexual harassment to unfair hiring and termination practices. One of the most notorious cases of caste discrimination in California involves Lakireddy Bali Reddy, an upper-caste landlord who trafficked and sexually abused more than two dozen Dalit girls.

you just now seeing this???

you just now seeing this???