FORBES 9/18/2012 @ 8:00AM 911,639 views

Chuck Feeney: The Billionaire Who Is Trying To Go Broke

This story appears in the October 8, 2012 issue of Forbes.

Comment Now

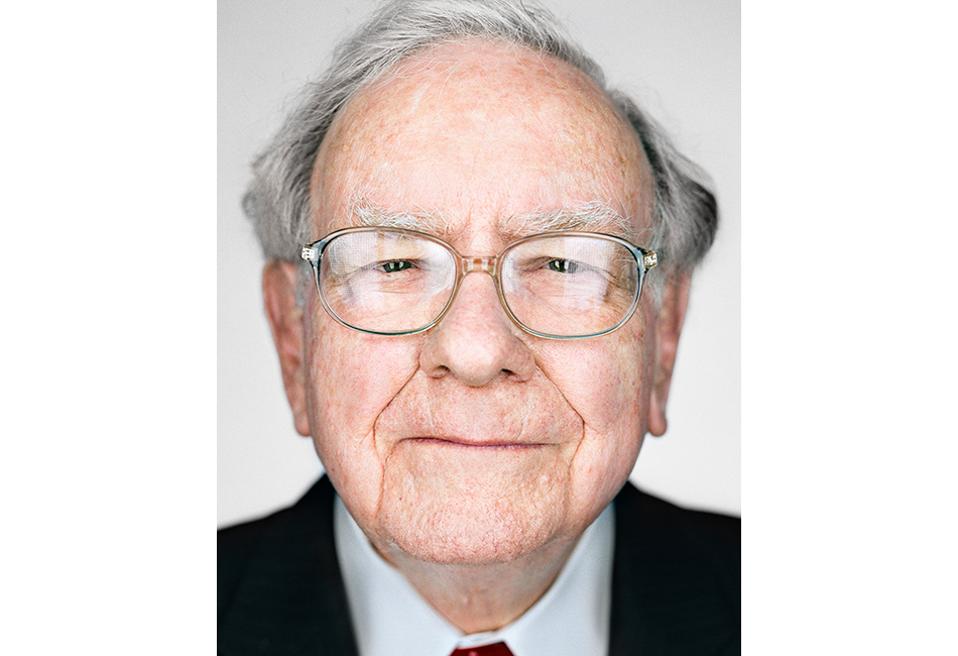

Chuck Feeney (David Cantwell for Forbes)

On a cool summer afternoon at Dublin’s Heuston Station, Chuck Feeney, 81, gingerly stepped off a train on his journey back from the University of Limerick, a 12,000-student college he willed into existence with his vision, his influence and nearly $170 million in grants, and hobbled toward the turnstiles on sore knees. No commuter even glanced twice at the short New Jersey native, one hand holding a plastic bag of newspapers, the other grasping an iron fence for support. The man who arguably has done more for Ireland than anyone since Saint Patrick slowly limped out of the station completely unnoticed. And that’s just how Feeney likes it.

Chuck Feeney is the James Bond of philanthropy. Over the last 30 years he’s crisscrossed the globe conducting a clandestine operation to give away a $7.5 billion fortune derived from hawking cognac, perfume and cigarettes in his empire of duty-free shops. His foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, has funneled $6.2 billion into education, science, health care, aging and civil rights in the U.S., Australia, Vietnam, Bermuda, South Africa and Ireland. Few living people have given away more, and no one at his wealth level has ever given their fortune away so completely during their lifetime. The remaining $1.3 billion will be spent by 2016, and the foundation will be shuttered in 2020. While the business world’s titans obsess over piling up as many riches as possible, Feeney is working double time to die broke.

Feeney embarked on this mission in 1984, in the middle of a decade marked by wealth creation–and conspicuous consumption–when he slyly transferred his entire 38.75% ownership stake in Duty Free Shoppers to what became the Atlantic Philanthropies. “I concluded that if you hung on to a piece of the action for yourself you’d always be worrying about that piece,” says Feeney, who estimates his current net worth at $2 million (with an “m”). “People used to ask me how I got my jollies, and I guess I’m happy when what I’m doing is helping people and unhappy when what I’m doing isn’t helping people.”

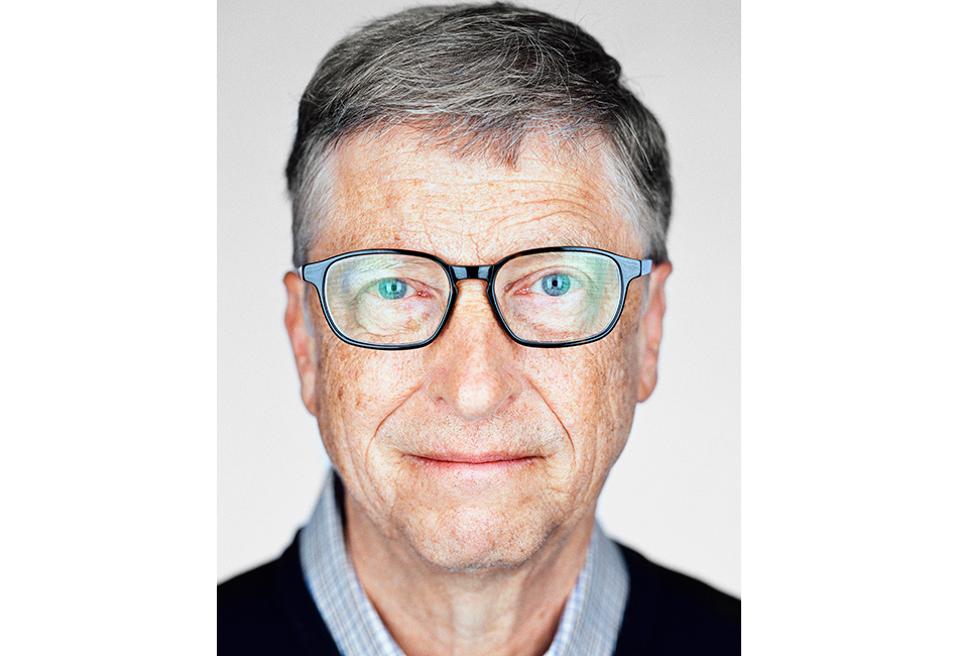

What Feeney does is give big money to big problems–whether bringing peace to Northern Ireland, modernizing Vietnam’s health care system or seeding $350 million to turn New York’s long-neglected Roosevelt Island into a technology hub. He’s not waiting to grant gifts after he’s gone nor to set up a legacy fund that annually tosses pennies at a $10 problem. He hunts for causes where he can have dramatic impact and goes all-in. “Chuck Feeney is a remarkable role model,” Bill Gates tells FORBES, “and the ultimate example of giving while living.”

In Pictures: 23 Billionaires Who Have Given Away $1 Billion Or More

For the first 15 years of this mission Feeney obsessively hid the type of donations that other tyc00ns employ publicists to plaster across newspapers. Many charities had no idea where the piles of money were coming from. Those that did were sworn to secrecy. “I had to convince the board of trustees that it was on the level, that there was nothing disreputable and this wasn’t Mafia money,” says Frank Rhodes, the former president of Cornell University who later chaired Atlantic Philanthropies. “That was difficult.” Eventually Feeney was outed ( in part due to FORBES), but his fervent desire for anonymity remained (until this year he had done about five interviews in his life). Now that his quest to give until nearly broke is coming to its conclusion, he’s opening up a bit. What emerges is one of strangest, most impactful lives of all time.

Feeney prefers showing to telling. In Dublin he sends me on a three-hour tour of Trinity College to witness everything from the library gift shop he designed to his genetics complex and department of neuroscience, complete with lab rats with electrodes implanted in their heads. The next day he endures the six-hour round-trip to the University of Limerick to personally walk me through its Irish World Academy of Music & Dance, its new medical school and its new sports center (now home to Ireland’s Munster rugby team), where hundreds of young kids were playing soccer on the all-weather turf. Rather than walk me through his life story, he invites Conor O’Clery , the author of the Feeney biography , The Billionaire Who Wasn’t (PublicAffairs, 2007), to dinner in Dublin’s Peploe’s Bistro. At dinner Feeney sits quietly in a frayed navy blazer, sipping chardonnay that he dilutes with a splash of water, occasionally throwing in a point for emphasis or, more often, a witty, self-deprecating joke.

The story that emerges is this: Feeney grew up in an Irish-American neighborhood in the blue-collar town of Elizabeth, N.J., coming of age in the Great Depression. He served in the Air Force during the Korean War before attending the Cornell School of Hotel Administration on the GI Bill. After graduation in 1956 he traveled to France to take more college classes and later got involved in the business of following the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic fleet, selling tax-free booze to sailors. Competition was intense, but he got ahead by using his military experience to talk his way directly onto ships and gathering intelligence on the fleet’s next destination by chatting up local prostitutes.

He brought fellow Cornell alum Bob Miller into the business, and the pair started selling cars, perfume and jewelry to servicemen and tourists. They later added tax lawyer Tony Pilaro and accountant Alan Parker as owners to help manage the bootstrapped business more professionally. By 1964 their Duty Free Shoppers had 200 employees in 27 countries.

It was a nice little business, but soon the Japanese economic boom would transform the scrappy operation into one of the most profitable retailers in history. In 1964, the same year as the Tokyo Olympics, Japan lifted foreign travel restrictions (enacted after World War II to rebuild the economy), allowing citizens to vacation abroad. Japanese tourists, along with their massive store of pent-up savings, surged across the globe. Hawaii and Hong Kong were top destinations. Feeney, who had picked up some Japanese language and customs while in the Air Force, hired smart, pretty Japanese girls to work the stores and filled his shelves with cognac, cigarettes and leather bags that gift-crazy Japanese snatched up for co-workers and friends. Soon Feeney and company had tour guides on the payroll who herded tourists to DFS stores before they had even checked into the hotel so they couldn’t spend money anywhere else first.

The Japanese were such lucrative customers that Feeney hired analysts to predict which cities they’d flock to next. DFS shops sprung up in Anchorage, San Francisco and Guam. Another target was Saipan, a tiny tropical island just a short flight from Japan that he predicted could become a hot beach spot for Tokyo residents. There was a catch: The island lacked an airport. So in 1976 DFS invested $5 million to have one built.

The aggressive growth strategy placed DFS in the perfect position for the subsequent Japanese economic explosion. Feeney received annual dividend payouts worth $12,000 in 1967, according to O’Clery. His payout in 1977? Twelve million dollars. Over the next decade Feeney banked nearly $334 million in dividends that he plowed into hotels, retail shops, clothing companies and, later, tech startups. He remained obsessively secretive and low key, but the money was now too big to ignore.

In 1988 The Forbes 400 issue included a four-page feature that exposed the success of DFS and the vast wealth of its four owners. The story by Andrew Tanzer and Marc Beauchamp, and the subsequent attention, was so jarring to Feeney that O’Clery devoted an entire chapter of his biography to the episode. The article pulled back the curtain on how DFS operated: its Japan strategy, the 200% markups, the 20% margins and blistering annual sales of roughly $1.6 billion. FORBES estimated that Feeney’s Waikiki shop annually generated $20,000 of revenue per square foot–$38,700 in current dollars, more than seven times Apple’s current average of $5,000. “My reaction was, ?Well, there goes our cover, ‘ ” says Feeney. “ We tried to figure out if it did us any damage but concluded no, the info was in the public domain.” The piece identified Feeney as the 31st-richest person in America, worth an estimated $1.3 billion. His secret was out.

But FORBES had made two mistakes: First, the fortune was worth substantially more. And second, it no longer belonged to Feeney.

Only a close inner circle knew of the latter: that Feeney himself was worth at most a few million dollars and didn’t even own a car. Feeney’s team contemplated a secret meeting with Malcolm Forbes to see how they could set the record straight but in the end decided to let the issue go. Feeney would be listed on The Forbes 400 until 1996.

In Pictures: 23 Billionaires Who Have Given Away $1 Billion Or More

Although he had shifted his ownership to Atlantic via a complex Bahamas-based asset swap to minimize disclosure and taxes, Feeney continued to aggressively expand DFS, traveling the globe to conquer new markets, expand margins and outmaneuver rivals. He loved making money but had no need for it once it was made. Feeney was happy with simple things. He had grown up in a humble, hardworking house and watched his parents constantly help others. In an oft-told story, each morning his mother, Madaline, a nurse, would jump in the car and conveniently drive by a disabled neighbor as he walked to the bus just to give him a ride. This tradition of charity was not extended to business rivals. “I’m a competitive type of person whether it’s playing a game of basketball or playing business games,” says Feeney. “I don’t dislike money, but there’s only so much money you can use.”

The money was how Feeney kept score, and while it no longer flowed into his pocket, he helped rake in as much as possible as an active DFS board member throughout the 1990s. Since his foundation’s wealth was built on the illiquid stake in DFS, his grants lived and died on the cash dividends the company paid out–a major problem when the Gulf war and subsequent dive in global tourism restricted the once gushing cash flow to a trickle. Even as the economy recovered, a desire for the freedom of a cash pile, plus a gut instinct that DFS’ best days were behind it (Japan was clearly slowing down), motivated Feeney to push his three other partners to start looking for a suitor to buy DFS. There were few companies big enough to absorb and run the global operation. The French luxury powerhouse LVMH, helmed by billionaire Bernard Arnault, was the clear favorite. Feeney got owner Alan Parker on his side early. Pilaro and Miller would prove harder to convince.

For two years the four owners battled with themselves and Arnault over prices and deal terms. Each player brought their own high-powered attorneys into the scrum. “Every time I’d see a new a lawyer I’d say, ‘Holy Christ, how much are we paying this guy?’” Feeney laughs.

Chuck Feeney: The Billionaire Who Is Trying To Go Broke

This story appears in the October 8, 2012 issue of Forbes.

Comment Now

Chuck Feeney (David Cantwell for Forbes)

On a cool summer afternoon at Dublin’s Heuston Station, Chuck Feeney, 81, gingerly stepped off a train on his journey back from the University of Limerick, a 12,000-student college he willed into existence with his vision, his influence and nearly $170 million in grants, and hobbled toward the turnstiles on sore knees. No commuter even glanced twice at the short New Jersey native, one hand holding a plastic bag of newspapers, the other grasping an iron fence for support. The man who arguably has done more for Ireland than anyone since Saint Patrick slowly limped out of the station completely unnoticed. And that’s just how Feeney likes it.

Chuck Feeney is the James Bond of philanthropy. Over the last 30 years he’s crisscrossed the globe conducting a clandestine operation to give away a $7.5 billion fortune derived from hawking cognac, perfume and cigarettes in his empire of duty-free shops. His foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, has funneled $6.2 billion into education, science, health care, aging and civil rights in the U.S., Australia, Vietnam, Bermuda, South Africa and Ireland. Few living people have given away more, and no one at his wealth level has ever given their fortune away so completely during their lifetime. The remaining $1.3 billion will be spent by 2016, and the foundation will be shuttered in 2020. While the business world’s titans obsess over piling up as many riches as possible, Feeney is working double time to die broke.

Feeney embarked on this mission in 1984, in the middle of a decade marked by wealth creation–and conspicuous consumption–when he slyly transferred his entire 38.75% ownership stake in Duty Free Shoppers to what became the Atlantic Philanthropies. “I concluded that if you hung on to a piece of the action for yourself you’d always be worrying about that piece,” says Feeney, who estimates his current net worth at $2 million (with an “m”). “People used to ask me how I got my jollies, and I guess I’m happy when what I’m doing is helping people and unhappy when what I’m doing isn’t helping people.”

What Feeney does is give big money to big problems–whether bringing peace to Northern Ireland, modernizing Vietnam’s health care system or seeding $350 million to turn New York’s long-neglected Roosevelt Island into a technology hub. He’s not waiting to grant gifts after he’s gone nor to set up a legacy fund that annually tosses pennies at a $10 problem. He hunts for causes where he can have dramatic impact and goes all-in. “Chuck Feeney is a remarkable role model,” Bill Gates tells FORBES, “and the ultimate example of giving while living.”

In Pictures: 23 Billionaires Who Have Given Away $1 Billion Or More

For the first 15 years of this mission Feeney obsessively hid the type of donations that other tyc00ns employ publicists to plaster across newspapers. Many charities had no idea where the piles of money were coming from. Those that did were sworn to secrecy. “I had to convince the board of trustees that it was on the level, that there was nothing disreputable and this wasn’t Mafia money,” says Frank Rhodes, the former president of Cornell University who later chaired Atlantic Philanthropies. “That was difficult.” Eventually Feeney was outed ( in part due to FORBES), but his fervent desire for anonymity remained (until this year he had done about five interviews in his life). Now that his quest to give until nearly broke is coming to its conclusion, he’s opening up a bit. What emerges is one of strangest, most impactful lives of all time.

Feeney prefers showing to telling. In Dublin he sends me on a three-hour tour of Trinity College to witness everything from the library gift shop he designed to his genetics complex and department of neuroscience, complete with lab rats with electrodes implanted in their heads. The next day he endures the six-hour round-trip to the University of Limerick to personally walk me through its Irish World Academy of Music & Dance, its new medical school and its new sports center (now home to Ireland’s Munster rugby team), where hundreds of young kids were playing soccer on the all-weather turf. Rather than walk me through his life story, he invites Conor O’Clery , the author of the Feeney biography , The Billionaire Who Wasn’t (PublicAffairs, 2007), to dinner in Dublin’s Peploe’s Bistro. At dinner Feeney sits quietly in a frayed navy blazer, sipping chardonnay that he dilutes with a splash of water, occasionally throwing in a point for emphasis or, more often, a witty, self-deprecating joke.

The story that emerges is this: Feeney grew up in an Irish-American neighborhood in the blue-collar town of Elizabeth, N.J., coming of age in the Great Depression. He served in the Air Force during the Korean War before attending the Cornell School of Hotel Administration on the GI Bill. After graduation in 1956 he traveled to France to take more college classes and later got involved in the business of following the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic fleet, selling tax-free booze to sailors. Competition was intense, but he got ahead by using his military experience to talk his way directly onto ships and gathering intelligence on the fleet’s next destination by chatting up local prostitutes.

He brought fellow Cornell alum Bob Miller into the business, and the pair started selling cars, perfume and jewelry to servicemen and tourists. They later added tax lawyer Tony Pilaro and accountant Alan Parker as owners to help manage the bootstrapped business more professionally. By 1964 their Duty Free Shoppers had 200 employees in 27 countries.

It was a nice little business, but soon the Japanese economic boom would transform the scrappy operation into one of the most profitable retailers in history. In 1964, the same year as the Tokyo Olympics, Japan lifted foreign travel restrictions (enacted after World War II to rebuild the economy), allowing citizens to vacation abroad. Japanese tourists, along with their massive store of pent-up savings, surged across the globe. Hawaii and Hong Kong were top destinations. Feeney, who had picked up some Japanese language and customs while in the Air Force, hired smart, pretty Japanese girls to work the stores and filled his shelves with cognac, cigarettes and leather bags that gift-crazy Japanese snatched up for co-workers and friends. Soon Feeney and company had tour guides on the payroll who herded tourists to DFS stores before they had even checked into the hotel so they couldn’t spend money anywhere else first.

The Japanese were such lucrative customers that Feeney hired analysts to predict which cities they’d flock to next. DFS shops sprung up in Anchorage, San Francisco and Guam. Another target was Saipan, a tiny tropical island just a short flight from Japan that he predicted could become a hot beach spot for Tokyo residents. There was a catch: The island lacked an airport. So in 1976 DFS invested $5 million to have one built.

The aggressive growth strategy placed DFS in the perfect position for the subsequent Japanese economic explosion. Feeney received annual dividend payouts worth $12,000 in 1967, according to O’Clery. His payout in 1977? Twelve million dollars. Over the next decade Feeney banked nearly $334 million in dividends that he plowed into hotels, retail shops, clothing companies and, later, tech startups. He remained obsessively secretive and low key, but the money was now too big to ignore.

In 1988 The Forbes 400 issue included a four-page feature that exposed the success of DFS and the vast wealth of its four owners. The story by Andrew Tanzer and Marc Beauchamp, and the subsequent attention, was so jarring to Feeney that O’Clery devoted an entire chapter of his biography to the episode. The article pulled back the curtain on how DFS operated: its Japan strategy, the 200% markups, the 20% margins and blistering annual sales of roughly $1.6 billion. FORBES estimated that Feeney’s Waikiki shop annually generated $20,000 of revenue per square foot–$38,700 in current dollars, more than seven times Apple’s current average of $5,000. “My reaction was, ?Well, there goes our cover, ‘ ” says Feeney. “ We tried to figure out if it did us any damage but concluded no, the info was in the public domain.” The piece identified Feeney as the 31st-richest person in America, worth an estimated $1.3 billion. His secret was out.

But FORBES had made two mistakes: First, the fortune was worth substantially more. And second, it no longer belonged to Feeney.

Only a close inner circle knew of the latter: that Feeney himself was worth at most a few million dollars and didn’t even own a car. Feeney’s team contemplated a secret meeting with Malcolm Forbes to see how they could set the record straight but in the end decided to let the issue go. Feeney would be listed on The Forbes 400 until 1996.

In Pictures: 23 Billionaires Who Have Given Away $1 Billion Or More

Although he had shifted his ownership to Atlantic via a complex Bahamas-based asset swap to minimize disclosure and taxes, Feeney continued to aggressively expand DFS, traveling the globe to conquer new markets, expand margins and outmaneuver rivals. He loved making money but had no need for it once it was made. Feeney was happy with simple things. He had grown up in a humble, hardworking house and watched his parents constantly help others. In an oft-told story, each morning his mother, Madaline, a nurse, would jump in the car and conveniently drive by a disabled neighbor as he walked to the bus just to give him a ride. This tradition of charity was not extended to business rivals. “I’m a competitive type of person whether it’s playing a game of basketball or playing business games,” says Feeney. “I don’t dislike money, but there’s only so much money you can use.”

The money was how Feeney kept score, and while it no longer flowed into his pocket, he helped rake in as much as possible as an active DFS board member throughout the 1990s. Since his foundation’s wealth was built on the illiquid stake in DFS, his grants lived and died on the cash dividends the company paid out–a major problem when the Gulf war and subsequent dive in global tourism restricted the once gushing cash flow to a trickle. Even as the economy recovered, a desire for the freedom of a cash pile, plus a gut instinct that DFS’ best days were behind it (Japan was clearly slowing down), motivated Feeney to push his three other partners to start looking for a suitor to buy DFS. There were few companies big enough to absorb and run the global operation. The French luxury powerhouse LVMH, helmed by billionaire Bernard Arnault, was the clear favorite. Feeney got owner Alan Parker on his side early. Pilaro and Miller would prove harder to convince.

For two years the four owners battled with themselves and Arnault over prices and deal terms. Each player brought their own high-powered attorneys into the scrum. “Every time I’d see a new a lawyer I’d say, ‘Holy Christ, how much are we paying this guy?’” Feeney laughs.