NobodyReally

Superstar

Interesting article, looking forward to hearing what folks here think of it:

http://www.cnn.com/2014/09/11/us/white-minority/index.html?hpt=hp_c2

When you're the only white person in the room

By John Blake, CNN

updated 5:14 PM EDT, Thu September 11, 2014

Amanda Shaffer's entire world shifted when she became a white minority in a black high school.

"Busing: A White Girl's Tale" for an online magazine, Belt.

"They were in a place where there were more black people than white people and that is not usual for white people," she says.

Some white minorities become more afraid of what they see inside themselves.

When DeYoung was in college, he decided he was going to introduce himself to an attractive white freshman he spotted. But when he saw that woman walking across campus with two black men, he suddenly lost interest.

DeYoung rummaged through his mental attic to figure out why. The answer humbled him. He was a man who grew up buying the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s speeches and watching his father pastor a multiracial church, but he unearthed something ugly.

Bill Bradley, a former U.S. senator, pals around with his former teammates on the New York Knicks.

"I had fallen prey to the stereotype that a white woman involved with a black man is damaged goods, which goes back to the slave masters who taught people that black men were sexual animals," he says. "I thought, 'I don't have prejudice,' and then one of the oldest stereotypes struck me right in the face."

It can all sound so draining -- checking your motivations, trying not to offend black people. Isn't it easier to just declare as a white person that you don't see race?

DeYoung says that's actually a subtle way of insulting people of color.

"It diminishes people to not see their race and their culture," says DeYoung, who wrote a memoir about his racial journey entitled "Homecoming: A White Man's Journey through Harlem to Jerusalem."

"The reality is that race affects people's lives, and if you can't see race, you can't see the life they've lived."

You don't become an expert on race

There's a scene in the 1998 film "Primary Colors" in which a white Southern political operative tells this to a staid, uptight black campaign worker:

"I'm blacker than you are. I got some slave in me. I can feel it."

That scene captures a character familiar to some blacks: the white person who considers himself an honorary black person because he has a black girlfriend and likes hip-hop music.

Yet white people who spend time in an all-black setting seem to reach another conclusion:

"I don't think I can understand what it means to be black," says Williams, the Freedom Summer volunteer who joked that he forgot he was white. "It's much more than being a minority. It's a whole history."

That's something Joshua Packwood learned when he became the first white valedictorian at Morehouse College, a historically black college in Georgia that counts King as one of its graduates.

He says the black students he encountered were everything from punk rockers to hipsters to skateboarders to political conservatives who opposed affirmative action.

"If you ask me to define what black is, I'm not sure I can," says Packwood, who now lives in New York City with his wife and son and is the co-founder of Red Alder, an investment company.

Some whites who found themselves in the minority wrestled with a fear that's familiar to many people of color: Will people ever see past my race?

"I also have to 'prove' myself over and over again," DeYoung wrote in his memoir, "Homecoming." "Some persons of color may never fully trust me because I am white."

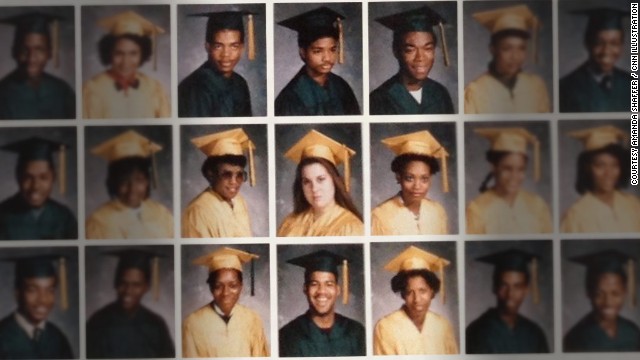

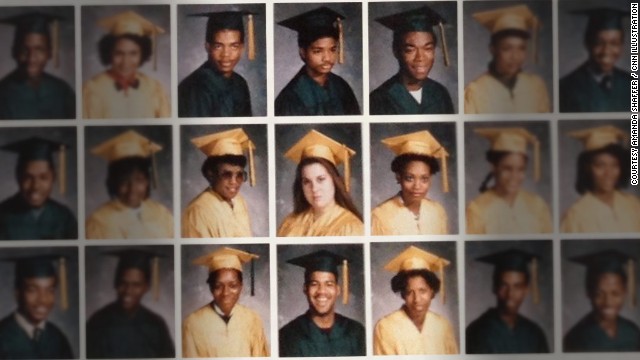

Curtiss Paul DeYoung, middle row second from the right, says some classmates called him a "white Negro."

The constant awareness of one's race can be exhausting. DeYoung quoted the theologian Howard Thurman in his memoir:

"The burden of being black and the burden of being white is so heavy that it is rare in our society to experience oneself as a human being."

But sometimes those moments can happen, as DeYoung learned by accident.

One day, DeYoung was looking through a journal he started keeping after he joined the church in Harlem. He noticed that the word "black" rang through every passage: I'm going to this "black church," I'm eating "black food," I'm making "black friends."

He recalled that no one at the Harlem church had ever placed a racial modifier before his name.

"Never once in that entire year did they refer to me as being white," he says. "I was just a member of the congregation. I was a child of God."

DeYoung kept reading and scanned the journal entries that came after he spent more time in the church. He noticed he was still writing about making new friends, listening to gospel and eating good food.

The word "black," however, had disappeared from his journal. They were no longer "the other." He was no longer an outsider.

He was at home.

http://www.cnn.com/2014/09/11/us/white-minority/index.html?hpt=hp_c2

When you're the only white person in the room

By John Blake, CNN

updated 5:14 PM EDT, Thu September 11, 2014

Amanda Shaffer's entire world shifted when she became a white minority in a black high school.

"Busing: A White Girl's Tale" for an online magazine, Belt.

"They were in a place where there were more black people than white people and that is not usual for white people," she says.

Some white minorities become more afraid of what they see inside themselves.

When DeYoung was in college, he decided he was going to introduce himself to an attractive white freshman he spotted. But when he saw that woman walking across campus with two black men, he suddenly lost interest.

DeYoung rummaged through his mental attic to figure out why. The answer humbled him. He was a man who grew up buying the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s speeches and watching his father pastor a multiracial church, but he unearthed something ugly.

Bill Bradley, a former U.S. senator, pals around with his former teammates on the New York Knicks.

"I had fallen prey to the stereotype that a white woman involved with a black man is damaged goods, which goes back to the slave masters who taught people that black men were sexual animals," he says. "I thought, 'I don't have prejudice,' and then one of the oldest stereotypes struck me right in the face."

It can all sound so draining -- checking your motivations, trying not to offend black people. Isn't it easier to just declare as a white person that you don't see race?

DeYoung says that's actually a subtle way of insulting people of color.

"It diminishes people to not see their race and their culture," says DeYoung, who wrote a memoir about his racial journey entitled "Homecoming: A White Man's Journey through Harlem to Jerusalem."

"The reality is that race affects people's lives, and if you can't see race, you can't see the life they've lived."

You don't become an expert on race

There's a scene in the 1998 film "Primary Colors" in which a white Southern political operative tells this to a staid, uptight black campaign worker:

"I'm blacker than you are. I got some slave in me. I can feel it."

That scene captures a character familiar to some blacks: the white person who considers himself an honorary black person because he has a black girlfriend and likes hip-hop music.

Yet white people who spend time in an all-black setting seem to reach another conclusion:

"I don't think I can understand what it means to be black," says Williams, the Freedom Summer volunteer who joked that he forgot he was white. "It's much more than being a minority. It's a whole history."

That's something Joshua Packwood learned when he became the first white valedictorian at Morehouse College, a historically black college in Georgia that counts King as one of its graduates.

He says the black students he encountered were everything from punk rockers to hipsters to skateboarders to political conservatives who opposed affirmative action.

"If you ask me to define what black is, I'm not sure I can," says Packwood, who now lives in New York City with his wife and son and is the co-founder of Red Alder, an investment company.

Some whites who found themselves in the minority wrestled with a fear that's familiar to many people of color: Will people ever see past my race?

"I also have to 'prove' myself over and over again," DeYoung wrote in his memoir, "Homecoming." "Some persons of color may never fully trust me because I am white."

Curtiss Paul DeYoung, middle row second from the right, says some classmates called him a "white Negro."

The constant awareness of one's race can be exhausting. DeYoung quoted the theologian Howard Thurman in his memoir:

"The burden of being black and the burden of being white is so heavy that it is rare in our society to experience oneself as a human being."

But sometimes those moments can happen, as DeYoung learned by accident.

One day, DeYoung was looking through a journal he started keeping after he joined the church in Harlem. He noticed that the word "black" rang through every passage: I'm going to this "black church," I'm eating "black food," I'm making "black friends."

He recalled that no one at the Harlem church had ever placed a racial modifier before his name.

"Never once in that entire year did they refer to me as being white," he says. "I was just a member of the congregation. I was a child of God."

DeYoung kept reading and scanned the journal entries that came after he spent more time in the church. He noticed he was still writing about making new friends, listening to gospel and eating good food.

The word "black," however, had disappeared from his journal. They were no longer "the other." He was no longer an outsider.

He was at home.