Column: A cop gouged out a black vet’s eyes. 73 years later, the SC town confronts it.

Brian Hicks

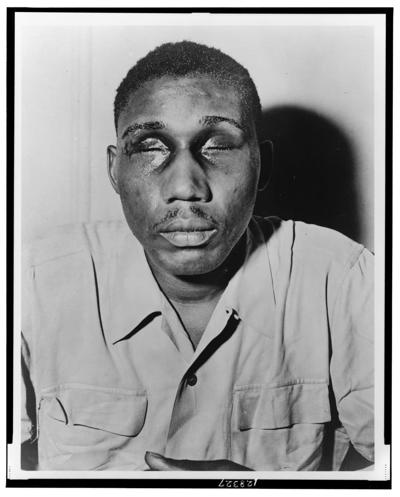

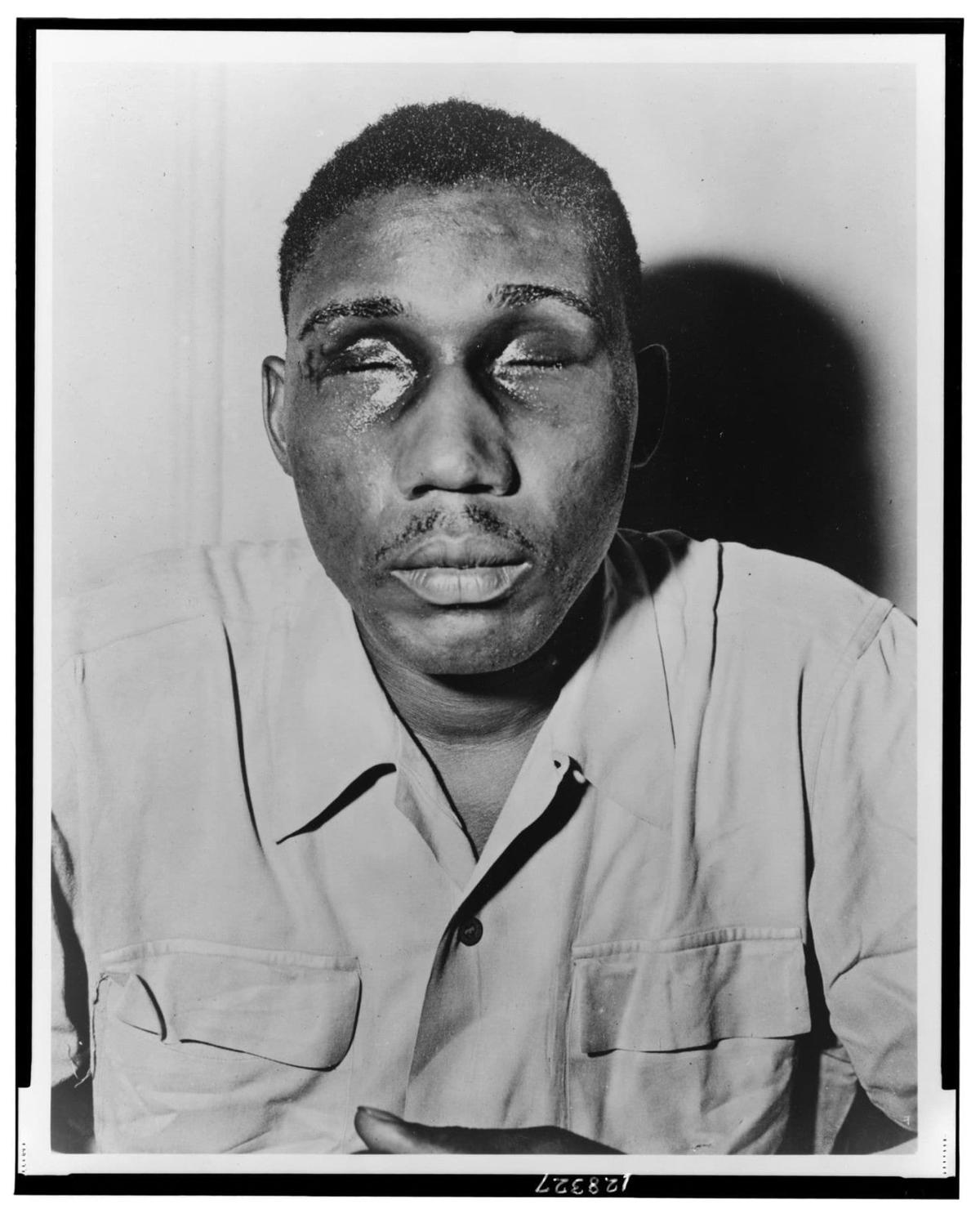

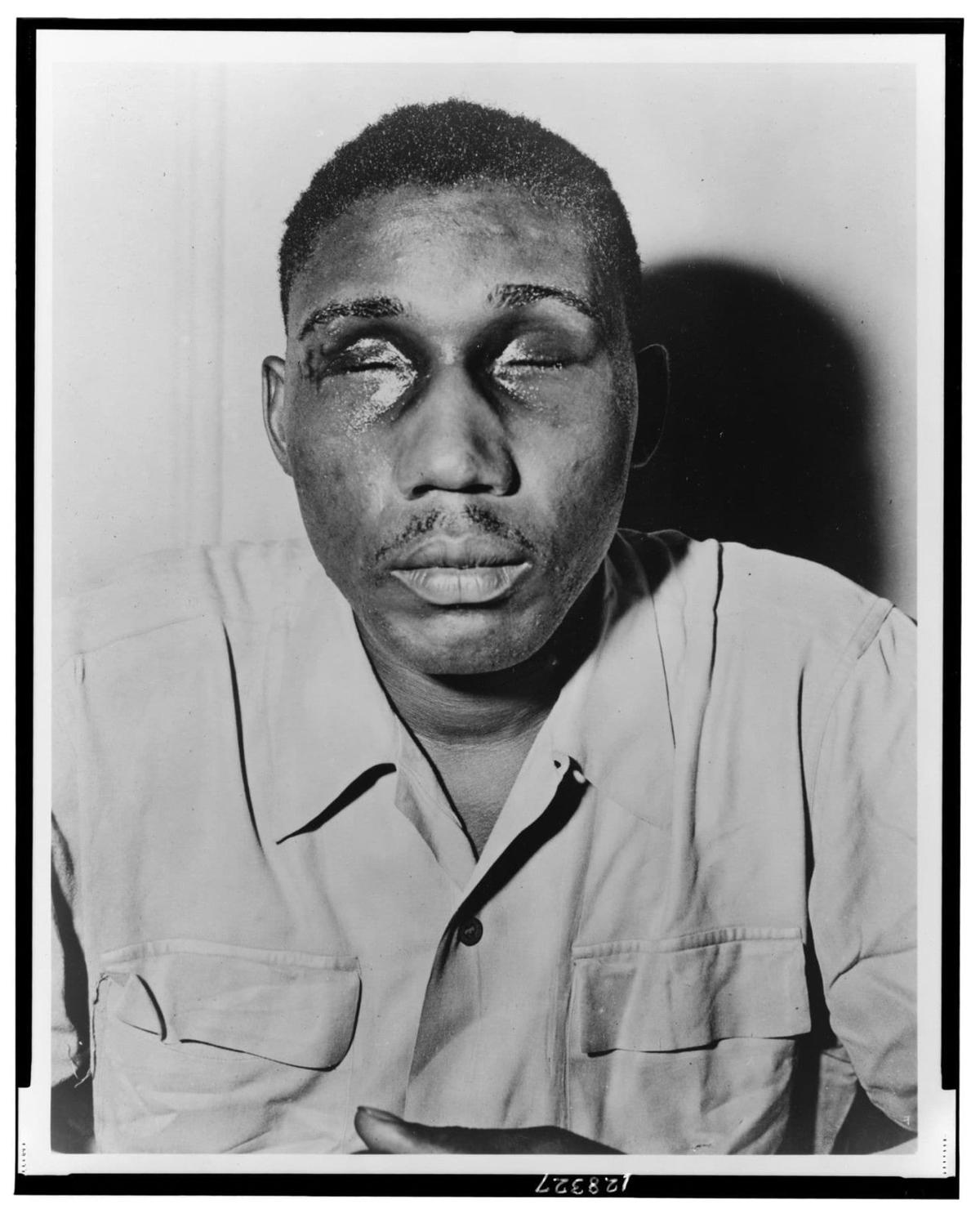

Decorated African-American World War II veteran Sgt. Isaac Woodard, who was beaten and blinded by a white police chief in Batesburg-Leesville in 1946. The brutality inflicted against Woodard by a Southern police chief is credited with inspiring President Harry Truman to integrate the military in 1948. J. DeBisse/Library of Congress, NAACP Records

https://www.postandcourier.com/content/tncms/live/#2

This 2018 photo shows a sign for the town of Batesburg-Leesville, S.C. where decorated African-American World War II veteran Sgt. Isaac Woodard was beaten and blinded by a white police chief in 1946. File/AP

Isaac Woodard just wanted to get home and see his wife.

He’d been in the Army more than three years, a longshoreman for the Pacific fleet in the waning days of World War II.

Finally, on Feb. 12, 1946, he was on a Greyhound bus bound for Winnsboro. But he wouldn’t make it — or ever see his wife again.

Because he was black, Woodard wasn’t allowed to fight during the war, but the decorated soldier would become one of the most infamous casualties of an ugly chapter in American history.

That night, Woodard asked the bus driver for a bathroom break just outside of Aiken. The driver was rude to him, later claiming the soldier was drunk and disturbing other passengers. Woodard took umbrage, but didn’t make a scene. When the bus stopped in Batesburg, however, the driver called the police. Woodard — still wearing his Army dress uniform — protested he’d done nothing wrong. But he was beaten and arrested.

And just outside the jail, the police chief took his blackjack and gouged out Woodard’s eyes.

The story shocked the country, and ultimately led President Truman to desegregate the military. But more than 70 years later, almost no one in the town where it happened knew about Woodard’s plight until researchers requested records pertaining to the incident.

Such stories aren’t proudly passed down from one generation to the next. Unlike some small Southern towns, which often ignore the troublesome elements of their past, Batesburg-Leesville (the two towns merged in 1993) has embraced Woodard’s tragedy and tried to make amends.

In June, the town expunged the sergeant’s 73-year-old criminal record. “Our Town Attorney Chris Spradley, Police Chief W. Wallace Oswald and Town Judge Robert Cook got together, reopened the case and dismissed the charges against Isaac Woodard,” Mayor Lancer Shull says. “Although Sgt. Woodard died in 1992 and has no direct descendants, we wanted to do something to make it right. As right as it can be.”

It is more justice than Woodard ever got in life. After his beating, Batesburg’s municipal court sentenced Woodard to 30 days in jail and fined him $50 before Police Chief Lynwood Shull (no relation to the current mayor) hurriedly delivered him to a veterans hospital in Columbia.

His family found him three weeks later, blind and suffering from partial amnesia. Woodard’s wife left him, unwilling to face a life as caregiver. Woodard’s parents took him to New York.

Because South Carolina officials refused to prosecute the chief, Truman ordered the Justice Department to charge Shull with violating Woodard’s civil rights.

Charleston Judge Waties Waring presided over that case and, like Truman, was appalled by Shull’s inevitable acquittal. It drove the judge into civil rights advocacy, culminating in a plot that eventually forced the U.S. Supreme Court to desegregate public schools in Brown v. Board of Education.

Ted Luckadoo, town manager of Batesburg-Leesville, says the community has been talking about the significance of Woodard’s story to the history of the civil rights movement, most people amazed to learn that such a horrific incident occurred on their streets. On Saturday, the town, which is 35 miles west of Columbia, will join with veterans groups to dedicate a historical marker to the “Blinding of Isaac Woodard” on the site of the old jail, which is now an empty lot.

Don North, a former Army major and military historian, led the charge to erect the marker along with help from U.S. District Judge Richard Gergel, who’s just published a book about the Woodard case, “Unexampled Courage.” The state approved the wording of the marker, and the town signed on as a sponsor.

“We jumped at the chance to be a part of this,” Luckadoo says. “It’s time to right the wrong and commemorate the progress that resulted from this.”

The president of the Disabled American Veterans will attend the ceremony, and says other vets from around the country will take part. The town bought a plane ticket for Woodard’s nephew, who cared for his uncle, to come from New York.

Judge Gergel, who often presides from the same bench where Waring once held court, says he’s been amazed by the thoughtful and empathetic reaction of the town. “They just thought it was the right thing to do, and everything they’ve done has been exemplary,” Gergel says. “You never know how good people can be.”

No, but Batesburg-Leesville is setting an example for the rest of the country.

Column: A cop gouged out a black vet's eyes. 73 years later, the SC town confronts it.

- Feb 7, 2019 Updated Feb 7, 2019

Brian Hicks

Decorated African-American World War II veteran Sgt. Isaac Woodard, who was beaten and blinded by a white police chief in Batesburg-Leesville in 1946. The brutality inflicted against Woodard by a Southern police chief is credited with inspiring President Harry Truman to integrate the military in 1948. J. DeBisse/Library of Congress, NAACP Records

https://www.postandcourier.com/content/tncms/live/#2

This 2018 photo shows a sign for the town of Batesburg-Leesville, S.C. where decorated African-American World War II veteran Sgt. Isaac Woodard was beaten and blinded by a white police chief in 1946. File/AP

- Christina L. Myers

Isaac Woodard just wanted to get home and see his wife.

He’d been in the Army more than three years, a longshoreman for the Pacific fleet in the waning days of World War II.

Finally, on Feb. 12, 1946, he was on a Greyhound bus bound for Winnsboro. But he wouldn’t make it — or ever see his wife again.

Because he was black, Woodard wasn’t allowed to fight during the war, but the decorated soldier would become one of the most infamous casualties of an ugly chapter in American history.

That night, Woodard asked the bus driver for a bathroom break just outside of Aiken. The driver was rude to him, later claiming the soldier was drunk and disturbing other passengers. Woodard took umbrage, but didn’t make a scene. When the bus stopped in Batesburg, however, the driver called the police. Woodard — still wearing his Army dress uniform — protested he’d done nothing wrong. But he was beaten and arrested.

And just outside the jail, the police chief took his blackjack and gouged out Woodard’s eyes.

The story shocked the country, and ultimately led President Truman to desegregate the military. But more than 70 years later, almost no one in the town where it happened knew about Woodard’s plight until researchers requested records pertaining to the incident.

Such stories aren’t proudly passed down from one generation to the next. Unlike some small Southern towns, which often ignore the troublesome elements of their past, Batesburg-Leesville (the two towns merged in 1993) has embraced Woodard’s tragedy and tried to make amends.

In June, the town expunged the sergeant’s 73-year-old criminal record. “Our Town Attorney Chris Spradley, Police Chief W. Wallace Oswald and Town Judge Robert Cook got together, reopened the case and dismissed the charges against Isaac Woodard,” Mayor Lancer Shull says. “Although Sgt. Woodard died in 1992 and has no direct descendants, we wanted to do something to make it right. As right as it can be.”

It is more justice than Woodard ever got in life. After his beating, Batesburg’s municipal court sentenced Woodard to 30 days in jail and fined him $50 before Police Chief Lynwood Shull (no relation to the current mayor) hurriedly delivered him to a veterans hospital in Columbia.

His family found him three weeks later, blind and suffering from partial amnesia. Woodard’s wife left him, unwilling to face a life as caregiver. Woodard’s parents took him to New York.

Because South Carolina officials refused to prosecute the chief, Truman ordered the Justice Department to charge Shull with violating Woodard’s civil rights.

Charleston Judge Waties Waring presided over that case and, like Truman, was appalled by Shull’s inevitable acquittal. It drove the judge into civil rights advocacy, culminating in a plot that eventually forced the U.S. Supreme Court to desegregate public schools in Brown v. Board of Education.

Ted Luckadoo, town manager of Batesburg-Leesville, says the community has been talking about the significance of Woodard’s story to the history of the civil rights movement, most people amazed to learn that such a horrific incident occurred on their streets. On Saturday, the town, which is 35 miles west of Columbia, will join with veterans groups to dedicate a historical marker to the “Blinding of Isaac Woodard” on the site of the old jail, which is now an empty lot.

Don North, a former Army major and military historian, led the charge to erect the marker along with help from U.S. District Judge Richard Gergel, who’s just published a book about the Woodard case, “Unexampled Courage.” The state approved the wording of the marker, and the town signed on as a sponsor.

“We jumped at the chance to be a part of this,” Luckadoo says. “It’s time to right the wrong and commemorate the progress that resulted from this.”

The president of the Disabled American Veterans will attend the ceremony, and says other vets from around the country will take part. The town bought a plane ticket for Woodard’s nephew, who cared for his uncle, to come from New York.

Judge Gergel, who often presides from the same bench where Waring once held court, says he’s been amazed by the thoughtful and empathetic reaction of the town. “They just thought it was the right thing to do, and everything they’ve done has been exemplary,” Gergel says. “You never know how good people can be.”

No, but Batesburg-Leesville is setting an example for the rest of the country.

Column: A cop gouged out a black vet's eyes. 73 years later, the SC town confronts it.