cole phelps

Superstar

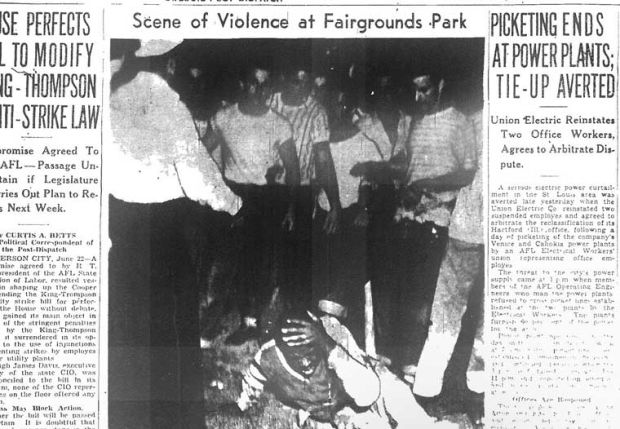

On June 21, 1949, opening day for the city’s pools, about thirty African American children entered the pool and swam with white children without incident. However, as they were swimming, a group gathered outside of the pool’s fence shouting threats at the African American swimmers. City police were called in to escort the black children out of the park when the swimming period ended around 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Conflicting eyewitness reports suggest simultaneously that the children were not subject to violence while they were under the police escort and that despite the police escort, white teenagers would periodically strike the black children without police reprisal. Reports of violence against African American youths were called into the city police throughout the 3 and 4 o’clock hours on this day.3

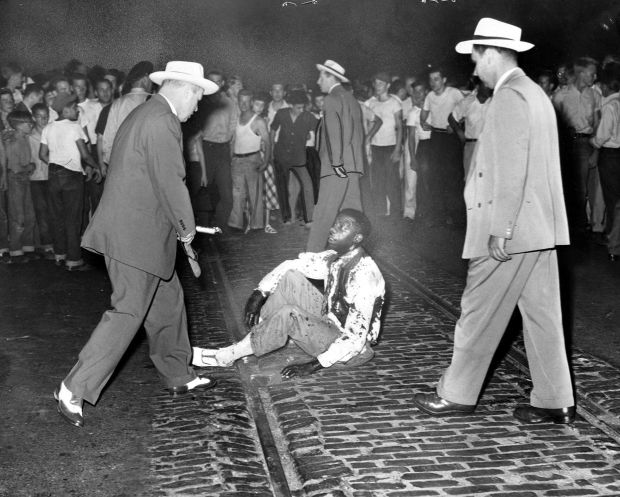

By 6:45 p.m., witnesses reported that a crowd of several hundred had gathered. Only 20 to 30 of the people gathered were African American youths. White boys with baseball bats surrounded a group of black boys, one of who was said to have a knife, and beat one of the African American youths until a police officer fell on top of the victim to stop the attack. At this point, the riot report suggests, the original crowd of several hundred swelled to the thousands as other park users and baseball fans on their way to Sportsman’s Park heeded the apparently false cry that an African American boy had killed a white youth. The violence that resulted required the involvement of nearly 150 police officers. Relative order was established by the 10 o’clock hour, though crowds did not disperse completely until after midnight.4 The mayor immediately reinstituted segregation policies in order to minimize the potential for future violence.

LIFE Magazine publicized the riot to a national audience in its July 4, 1949 issue, reporting eight arrests as a result of the violence, and noting that seven of the eight people arrested were injured. The magazine, however, did not provide information about the racial identities of those arrested or injured, instead highlighting the criminality and the bodily harm. However, the official report states that only seven people – three whites and four blacks – were arrested; this despite the fact that, of the six people who were seriously injured, five were African American. Three African Americans and one of the white youths who were arrested were ultimately charged with inciting a riot according to the official report.5 LIFE also claimed that 400 police officers intervened to restore order, as opposed to 150 officers as stated in the official report. These conflicting reports are probably the result of the purpose of each of these publications as the official report was to provide the political record of the event whereas the LIFE Magazine article played upon national concerns about racial integration.