DaRealness

I think very deeply

Forty years on from the New Cross fire, what has changed for black Britons?

In 1981, a blaze killed 13 black teenagers at a London house party in a suspected racist attack. What can be learned from the legacy of the outcry and activism that followed?

by Kehinde Andrews

Sun 17 Jan 2021 11.00 GMT

Although it happened before I was born, the New Cross fire in 1981 and the National Black People’s Day of Action that followed are landmarks in my identity; growing up in a Caribbean family in the 1980s, they are part of our collective memory. New Cross is fundamental because it contains all the features of racism that black people in Britain have long suffered: the racial violence, police abuse, neglect by the state; in turn, it tells us of the community’s resistance. Forty years on, recalling the events seems vital, especially in this moment of renewed optimism after the Black Lives Matter protests, because the legacies of New Cross still resonate.

On 18 January 1981, a fire tore through 439 New Cross Road in south-east London, where Yvonne Ruddock was celebrating her 16th birthday with about 60 guests. Wayne Hayes, who was 17 at the time, recalled the carnage in an interview for HuffPost last year. He described how dozens of teenagers and young people, trapped upstairs in the house after the stairs collapsed, resorted to jumping out of second-floor windows, how it was so hot “people’s skin was peeling back” and how in the aftermath he had 140 skin grafts. He shattered 163 bones and has been classed as disabled ever since. Thirteen young people were killed, more than 50 injured and one guest – Anthony Berbeck – died two years later at the age of 20. Many believe he took his own life as a result of the trauma of that night.

Film-maker Menelik Shabazz was 26 at the time and had been living in London since moving as a six-year-old from Barbados. To chronicle both the fire and the community response he made Blood Ah Go Run. “It was a historic moment that was important to document,” he says. The film includes testimony from Armza Ruddock, whose children Yvonne and Paul both died: “Every time I close my eyes I can only see the fire, and the children were screaming, and when they stopped screaming I said, oh God they’re dead.” Shabazz describes his reaction as similar to the experience people felt at Grenfell. “It’s a shock to our system to know that 13 young people ended up dead during a birthday party. People were very angry and upset.” Speaking to him and others it is clear that the anger remains palpable. Shabazz says “it was a racist attack” and it is a widely held assumption in black communities that the fire was started by fascists, most likely using a petrol bomb.

The flame-ravaged house in New Cross Road, Deptford, south London in 1981. Photograph: Geoffrey White/ANL/Shutterstock

A second inquest in 2004 accepted the fire was started deliberately, but rejected that it was a racist attack. (Coroner Gerald Butler said in his verdict: “While I think it probable ... that this fire was begun by deliberate application of a flame to the armchair near to the television ... I cannot be sure of this. The result is this, that in the case of each and every one of the deaths, I must return an open verdict.” He said he was satisfied that the fire was not started by a petrol bomb or any other incendiary device, either thrown from outside or inside the house in New Cross Road.) No one has ever been charged in connection with the fire and the case remains unsolved, leading to a complete lack of faith in the official investigations. Collectively, we remember the event as the “New Cross massacre”, where there has been no justice for 14 black young people.

Local history appeared to support the theory that the fire was a racist attack. Ten years before, in 1971, a Caribbean house party had been attacked by firebomb in Sunderland Road, in nearby Forest Hill, leaving 22 injured. And just three years before in 1978, Deptford’s Albany Empire community theatre was burned down, with the National Front claiming responsibility. This was the era of far-right extremism, marked by violent racist attacks that Britain prefers to forget. I am old enough to have walked to school and seen chalk directions to NF meetings. But I am young enough to have missed the daily violence and could naively wonder whether the letters stood for “New Flowers”. Chanté Joseph, who is writing a book on British black power, stresses the need to remind people that in recent history “white people in this country made bombs and threw them at us”.

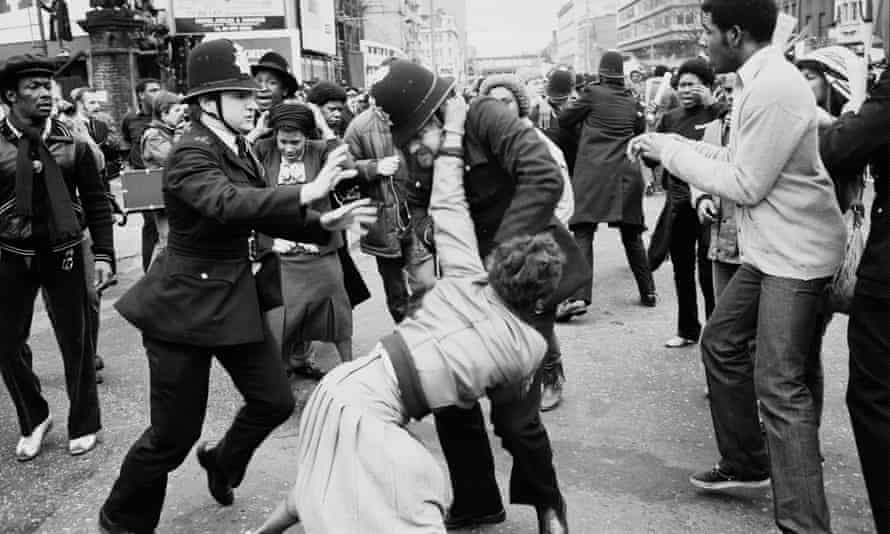

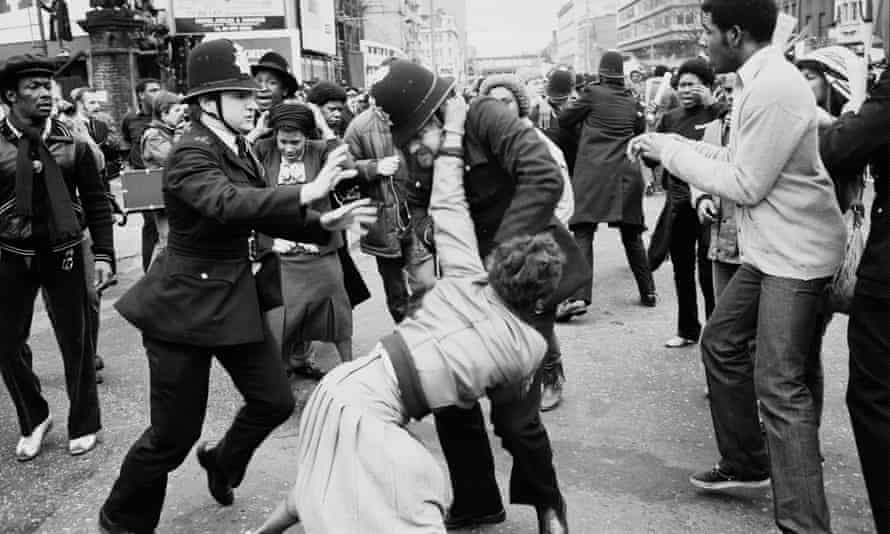

Violent scenes during the protest march that followed the fire in March 1981. Photograph: Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Caribbean house parties were a particular target. In the month after the New Cross fire, rightwing Tory MP Jill Knight raised the issue in parliament, calling for such “noisy” gatherings to be banned on the grounds of public safety, citing race relations legislation as a reason the police’s hands were tied.

There was already a lack of trust among black communities in the official response and a general perception of the police as racist and discriminatory. Abuse of the so-called “sus laws”, for example, which allowed police to not only stop and search but actually take people into custody on mere suspicion, was a constant issue. Police raids on parties and accusations of brutality were ever present. David Michael, the first black police officer to serve in Lewisham in the 1970s (New Cross is part of the borough), described the force as behaving like an “occupying army”. Unfortunately, this is the approach many felt they took to the investigation of the New Cross fire. The line of inquiry into a firebombing was quickly dropped in favour of a theory that a fight had broken out and that the unruly black youth had caused their own deaths. A number of the survivors were detained for questioning and activists exposed how children were encouraged to sign false statements. The story of Denise Gooding is recounted by Carol Pierre in Black British History: New Perspectives. At just 11 years old, Gooding was subject to hours of questioning into the early morning and pressured to admit there was fighting at the party. Cecil Gutzmore, the academic and activist who was active in the mobilisations after the fire, explained to me that “almost immediately victims became suspects”.

It was not only the police response that fed into community anger. Such a tragedy should have provoked national mourning but there was silence. A month later, when 45 people were killed at a Dublin disco, the Queen and the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, immediately sent their condolences. It took Thatcher five weeks to reply to Sybil Phoenix, who had written on behalf of the New Cross families and community, condemning “the failure of… government to reflect the outrage… of the black community”. Thatcher’s disrespect was summed up in her request to Phoenix to pass on her sympathies rather than making any effort to contact the families herself. The lack of an official response to New Cross demonstrated the value placed on black lives in Britain. The media were largely silent or supported the view that the black youngsters had caused the fire themselves. The anger is evident in Gutzmore’s voice as he recalls the silence from those in authority and the New Cross campaigners’ “13 dead, nothing said” slogan.

In 1981, a blaze killed 13 black teenagers at a London house party in a suspected racist attack. What can be learned from the legacy of the outcry and activism that followed?

by Kehinde Andrews

Sun 17 Jan 2021 11.00 GMT

Although it happened before I was born, the New Cross fire in 1981 and the National Black People’s Day of Action that followed are landmarks in my identity; growing up in a Caribbean family in the 1980s, they are part of our collective memory. New Cross is fundamental because it contains all the features of racism that black people in Britain have long suffered: the racial violence, police abuse, neglect by the state; in turn, it tells us of the community’s resistance. Forty years on, recalling the events seems vital, especially in this moment of renewed optimism after the Black Lives Matter protests, because the legacies of New Cross still resonate.

On 18 January 1981, a fire tore through 439 New Cross Road in south-east London, where Yvonne Ruddock was celebrating her 16th birthday with about 60 guests. Wayne Hayes, who was 17 at the time, recalled the carnage in an interview for HuffPost last year. He described how dozens of teenagers and young people, trapped upstairs in the house after the stairs collapsed, resorted to jumping out of second-floor windows, how it was so hot “people’s skin was peeling back” and how in the aftermath he had 140 skin grafts. He shattered 163 bones and has been classed as disabled ever since. Thirteen young people were killed, more than 50 injured and one guest – Anthony Berbeck – died two years later at the age of 20. Many believe he took his own life as a result of the trauma of that night.

Film-maker Menelik Shabazz was 26 at the time and had been living in London since moving as a six-year-old from Barbados. To chronicle both the fire and the community response he made Blood Ah Go Run. “It was a historic moment that was important to document,” he says. The film includes testimony from Armza Ruddock, whose children Yvonne and Paul both died: “Every time I close my eyes I can only see the fire, and the children were screaming, and when they stopped screaming I said, oh God they’re dead.” Shabazz describes his reaction as similar to the experience people felt at Grenfell. “It’s a shock to our system to know that 13 young people ended up dead during a birthday party. People were very angry and upset.” Speaking to him and others it is clear that the anger remains palpable. Shabazz says “it was a racist attack” and it is a widely held assumption in black communities that the fire was started by fascists, most likely using a petrol bomb.

The flame-ravaged house in New Cross Road, Deptford, south London in 1981. Photograph: Geoffrey White/ANL/Shutterstock

A second inquest in 2004 accepted the fire was started deliberately, but rejected that it was a racist attack. (Coroner Gerald Butler said in his verdict: “While I think it probable ... that this fire was begun by deliberate application of a flame to the armchair near to the television ... I cannot be sure of this. The result is this, that in the case of each and every one of the deaths, I must return an open verdict.” He said he was satisfied that the fire was not started by a petrol bomb or any other incendiary device, either thrown from outside or inside the house in New Cross Road.) No one has ever been charged in connection with the fire and the case remains unsolved, leading to a complete lack of faith in the official investigations. Collectively, we remember the event as the “New Cross massacre”, where there has been no justice for 14 black young people.

Local history appeared to support the theory that the fire was a racist attack. Ten years before, in 1971, a Caribbean house party had been attacked by firebomb in Sunderland Road, in nearby Forest Hill, leaving 22 injured. And just three years before in 1978, Deptford’s Albany Empire community theatre was burned down, with the National Front claiming responsibility. This was the era of far-right extremism, marked by violent racist attacks that Britain prefers to forget. I am old enough to have walked to school and seen chalk directions to NF meetings. But I am young enough to have missed the daily violence and could naively wonder whether the letters stood for “New Flowers”. Chanté Joseph, who is writing a book on British black power, stresses the need to remind people that in recent history “white people in this country made bombs and threw them at us”.

Violent scenes during the protest march that followed the fire in March 1981. Photograph: Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Caribbean house parties were a particular target. In the month after the New Cross fire, rightwing Tory MP Jill Knight raised the issue in parliament, calling for such “noisy” gatherings to be banned on the grounds of public safety, citing race relations legislation as a reason the police’s hands were tied.

There was already a lack of trust among black communities in the official response and a general perception of the police as racist and discriminatory. Abuse of the so-called “sus laws”, for example, which allowed police to not only stop and search but actually take people into custody on mere suspicion, was a constant issue. Police raids on parties and accusations of brutality were ever present. David Michael, the first black police officer to serve in Lewisham in the 1970s (New Cross is part of the borough), described the force as behaving like an “occupying army”. Unfortunately, this is the approach many felt they took to the investigation of the New Cross fire. The line of inquiry into a firebombing was quickly dropped in favour of a theory that a fight had broken out and that the unruly black youth had caused their own deaths. A number of the survivors were detained for questioning and activists exposed how children were encouraged to sign false statements. The story of Denise Gooding is recounted by Carol Pierre in Black British History: New Perspectives. At just 11 years old, Gooding was subject to hours of questioning into the early morning and pressured to admit there was fighting at the party. Cecil Gutzmore, the academic and activist who was active in the mobilisations after the fire, explained to me that “almost immediately victims became suspects”.

It was not only the police response that fed into community anger. Such a tragedy should have provoked national mourning but there was silence. A month later, when 45 people were killed at a Dublin disco, the Queen and the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, immediately sent their condolences. It took Thatcher five weeks to reply to Sybil Phoenix, who had written on behalf of the New Cross families and community, condemning “the failure of… government to reflect the outrage… of the black community”. Thatcher’s disrespect was summed up in her request to Phoenix to pass on her sympathies rather than making any effort to contact the families herself. The lack of an official response to New Cross demonstrated the value placed on black lives in Britain. The media were largely silent or supported the view that the black youngsters had caused the fire themselves. The anger is evident in Gutzmore’s voice as he recalls the silence from those in authority and the New Cross campaigners’ “13 dead, nothing said” slogan.