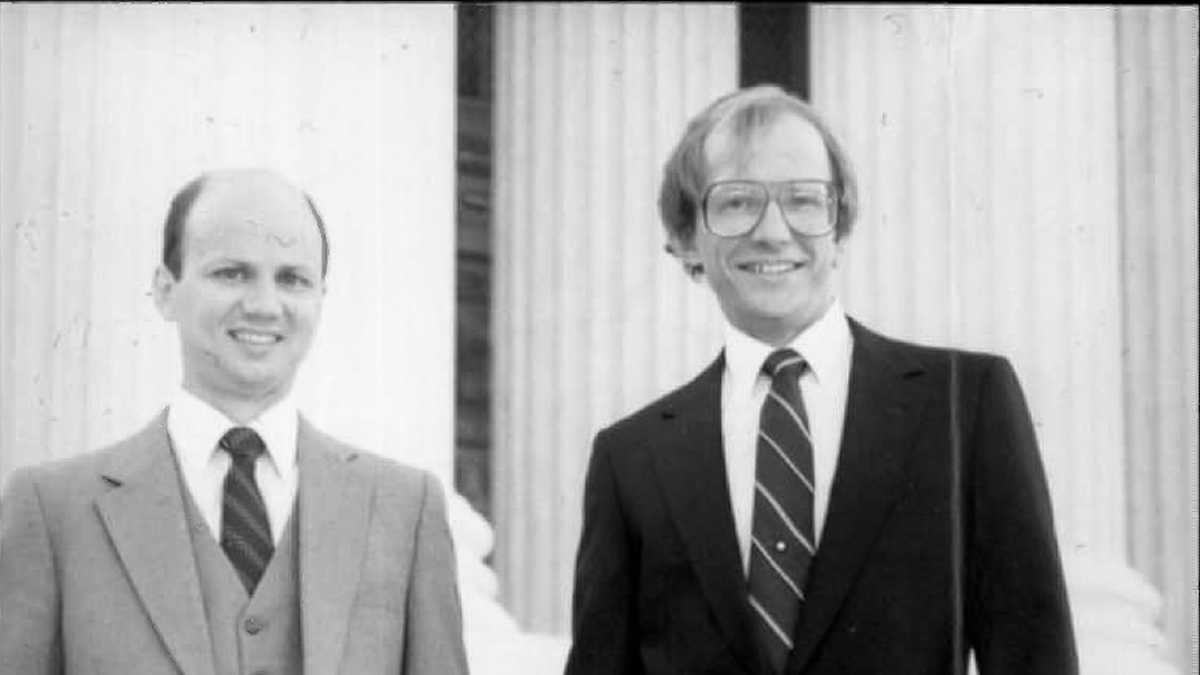

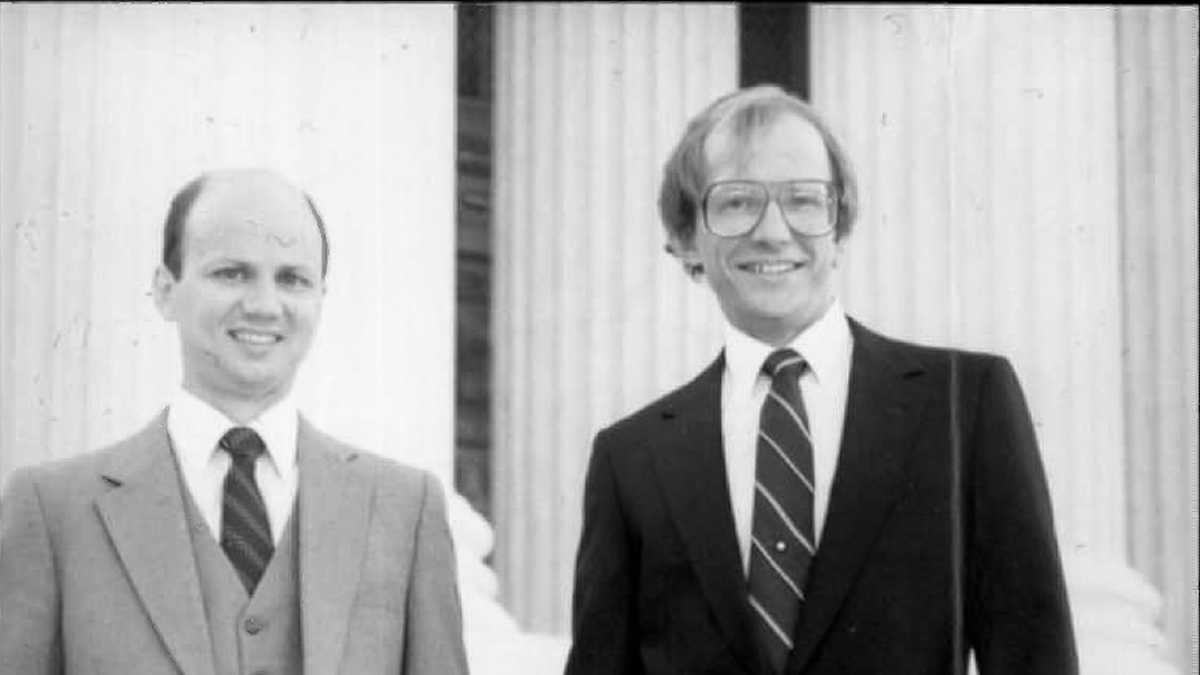

Courtesy of Verlin Meinz

Public defenders Peter Carusona (left) and Verlin Meinz (right) on the steps of the United State Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. in April 1986, to argue on behalf of Terry Allen.

In a recording of the arguments that day, Meinz laid out his client’s case to the Supreme Court justices.

“As I speak to the court this morning, the petitioner, Terry Allen is incarcerated in a maximum security penal institution in the state of Illinois,” Meinz said. “The petitioner, though, has not faced trial for a crime.”

Meinz argued that Allen’s incarceration was unconstitutional because he was being punished without ever being proved guilty. He said Allen was not being treated effectively.

“I had toured that institution, I had been inside of cells,” Meinz said in a recent phone interview. “I knew precisely what a day in the life of a sexually dangerous person looked like compared to a day in the life of another sex offender who had been processed in a criminal case — they’re treated precisely the same.”

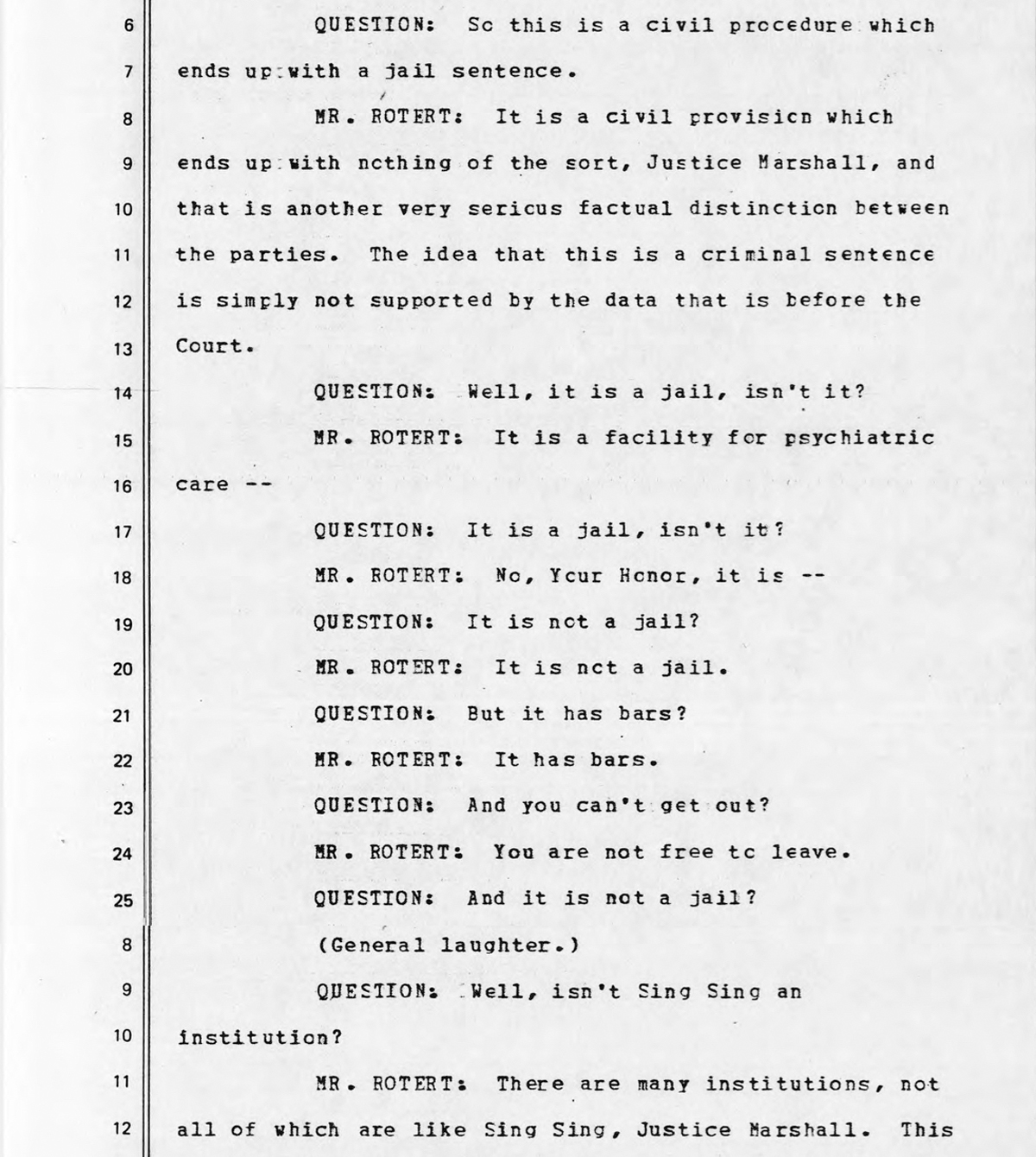

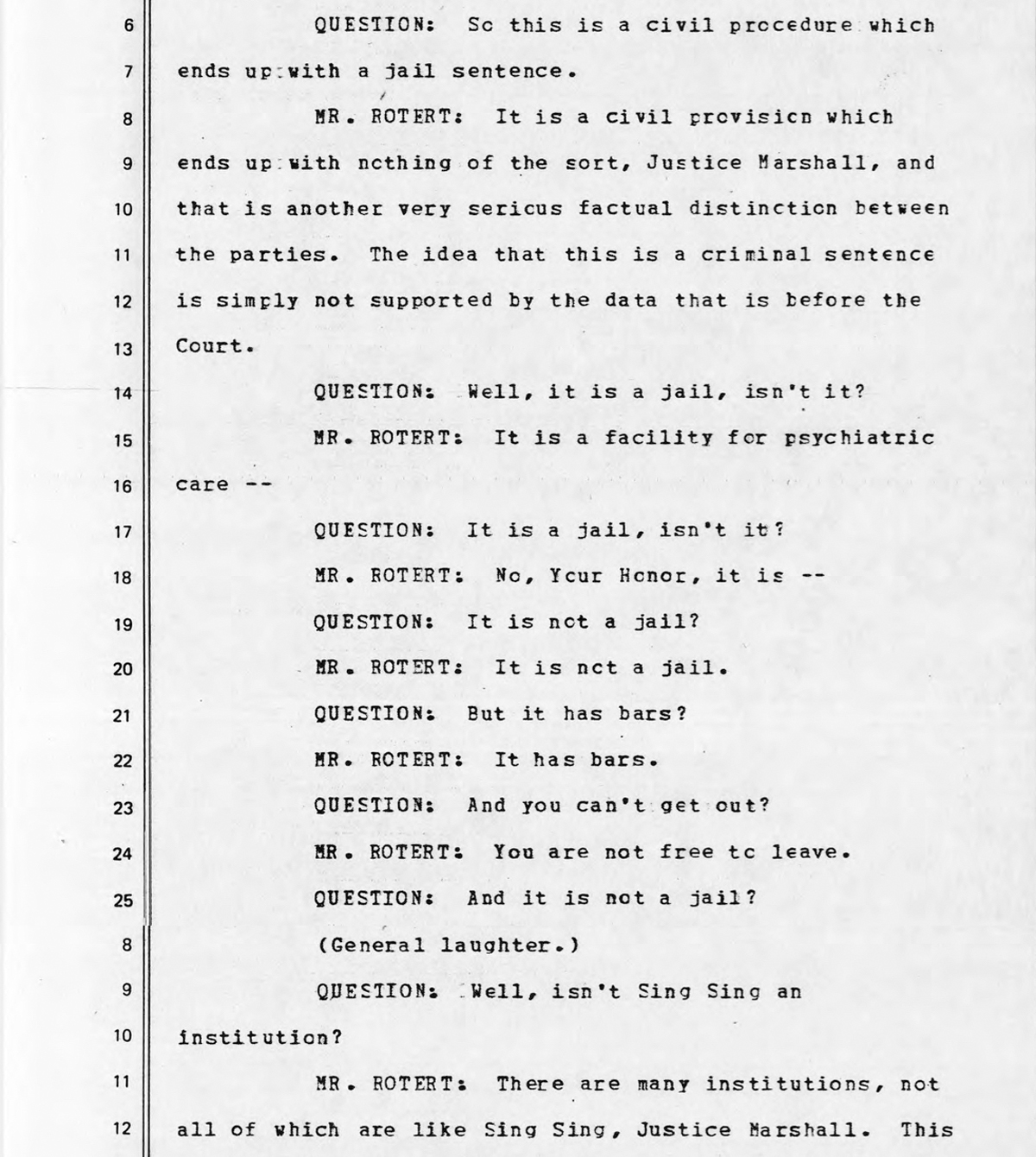

Mark Rotert, a then-assistant attorney general for Illinois, argued on behalf of the state.

“I got up and I probably said about two syllables when Justice Thurgood Marshall took me to task a little bit,” Rotert said. “It was on a point that is in the case itself a very essential point: Is the functional treatment being given to Mr. Allen demonstrating that this should be looked at as essentially a criminal proceeding?”

Rotert and Marshall argued about whether or not Allen was in a treatment facility.

Rotert didn’t sway Marshall, but he did convince five of the other justices. Allen lost the case 5-4. The majority decided that Illinois had demonstrated the Sexually Dangerous Persons Act was different enough from a criminal process, that the way Allen was being detained for therapy was constitutional.

Despite the loss, Allen found a glimmer of hope in the decision. The justices referred to a part of the Illinois law saying people may be released after the briefest time in confinement, as soon as they're better.

“After hearing that, I told myself this is good news,” Allen said. “That was like a relief to hear that.”

Indefinite treatment

The decision meant he would still have to prove he was cured before getting out, which is often a long and difficult process for many SDPs in Illinois.

To be successful in therapy, SDPs like Allen have to express remorse for what they did, apologize, and show empathy for their victims. They also have to talk about how they can avoid committing crimes in the future.

The treatment program consists of four phases, but moving through them doesn’t mean a prisoner is released. And getting in trouble — for anything from having an untucked shirt, to arguing with staff — can prevent SDPs from moving into the next phase of therapy.

Manuel Martinez/WBEZ

Civilly committed inmates at Big Muddy River Correctional Center live like prisoners convicted of felonies, but they have no release dates.

An analysis of prison records by WBEZ shows about 10 people in the SDP program at Big Muddy River have died since 2012. In that same time, 10 were granted conditional releases. Two were fully discharged from the program. The average length of stay for SDPs currently incarcerated in the program is about 17 years.

“A high degree of certainty”

Many of the people locked up under the SDP Act in Illinois are there because of a retired prosecutor named Sheryl Essenburg. Today, she spends her days teaching at the University of Illinois campus in Springfield.

When asked about the number of people she’d put behind bars using the SDP Act without getting criminal convictions, she laughed.

“There was a story for a long time that there was the ‘Sheryl Essenburg Wing’ down at Big Muddy, to house, you know, the inmates I had sent there,” Essenburg said.

Today, about 25 percent of the people detained under the law in Illinois are from the relatively small Sangamon County in central Illinois where Essenburg was an assistant state’s attorney for more than 30 years.

Essenburg said she first came across the civil commitment statute in the early 1990s. She was working on a sex abuse case where a boy had allegedly been repeatedly abused by a close family friend. Essenberg didn’t want to have to put the victim on the witness stand, and then a colleague mentioned the possibility of seeking a civil commitment, a process in which they could try to incarcerate the man without the need for a criminal trial and the boy's testimony.

“It didn't seem like the traditional way of prosecuting would probably work in this case, so I thought, well, here’s an alternative.” Essenburg said.

Essenburg became an expert on the law, and started training other prosecutors across the state in how they could use it in cases where a normal conviction might be difficult. In 2011, she wrote a manual,

A Prosecutor’s Guide to the Illinois Sexually Dangerous Persons Act, which educates prosecutors on this type of civil commitment, instructs them on how to lock people up using the law, and how to keep them behind bars.

Manuel Martinez/WBEZ

Sheryl Essenburg worked as a prosecutor with the Sangamon County State’s Attorney’s office in Springfield for more than 30 years. She wrote a manual to teach others how to use the Sexually Dangerous Persons Act to win civil commitments.

“If there is a legal way that I can prevent a person who is in my mind pretty clearly going to commit that next offense — if I can intervene before he commits that next offense with a high degree of certainty — then I’m gonna do that,” she said.

Despite Essenburg’s confidence in the law, and its necessity, it’s questionable whether the state program set up to treat sexually dangerous persons is equipped to do so effectively. State records show the prison where SDPs are indefinitely incarcerated employed just one or two staff psychiatrists for the entire population. There are 171 SDPs currently locked up in Illinois.

In a statement in response to this story, a spokesperson for the Illinois Department of Corrections said the agency is actively recruiting and hiring licensed sex offender treatment providers.

The John Howard Association, a nonpartisan prison watchdog group, has also raised the concern that many people in the program are low-IQ and diagnosed with intellectual or learning disabilities, which could make it harder for them to convincingly argue that they're better and they should be released from prison.

A recent intelligence test puts Allen on the borderline between low and extremely low IQ.

Mark Heyrman, a law professor at the University of Chicago, said he doesn't know why the state is housing these people in prison and why it's been doing it for decades.

Manuel Martinez/WBEZ

University of Chicago clinical law professor Mark Heyrman led a governor’s commission that in 1988 reviewed the Illinois Sexually Dangerous Persons Act and recommended it be abolished.

“What sense does it make to have the department of corrections do this? Why aren’t they in the custody of the department of human services that runs our seven state psychiatric hospitals?” Heyrman said.

Heyrman said once the state has people in the program locked up, it’s essentially impossible to say with certainty they’re “recovered,” and there’s little incentive to ever release them.

“If I say ‘no you can’t get out,’ no one will ever complain,” Heyrman said. “If I say ‘yes,’ it’s almost certain that I will make a mistake.”

In 1988, Heyrman led a governor-appointed commission of two dozen legislators, experts, and law enforcement officials tasked with reviewing criminal and mental health law, including the SDP Act.

The commission worked for a year, and then made a series of recommendations based on what they found.

“Among the recommendations is a recommendation about the Sexually Dangerous Persons Act,” he said. “The commission recommended that it be abolished.”

Heyrman said that recommendation didn’t gain support for a number of reasons, including optics.

“The problem isn't just sort of thinking about what's the smartest thing to do, there are appearances, and those appearances are sometimes contradictory to what's the smartest thing to do,” Heyrman said.

Free, but imprisoned

Allen has filed a number of petitions over the years, asking to be released. He’s had at least a dozen hearings to make a case that he should be let go. In 2015, after 30 years in prison, he was granted conditional release after he asked that his petition be heard by a jury, something SDPs can request.

During the hearing, the state’s psychiatrist pointed to Allen’s nearly 250 rule violations during his time in the SDP program as one possible reason Allen hadn’t won release in the past. In his testimony the state psychiatrist said, “according to the DOC, the average offender has one or two or one to three institutional violations a year.”

But at the hearing, a psychologist hired by Allen’s team challenged the state’s expert.

According to Allen's attorneys, the independent evaluator recruited by Allen’s team said the state's findings that Allen wasn’t ready for release after more then three decades were biased, intentionally deceptive, and a “hatchet job.”

The jury at that hearing found Allen was fit to be released. But, like many things in the criminal justice system, it wasn’t quite so straight forward. When SDPs in Illinois are granted conditional release, even without a conviction, they are listed as sex offenders. That means they need a place to live that conforms to the very strict rules of the sex offender registry. It means Allen can’t live near parks, schools, or halfway houses, among numerous other restrictions.

“The state says that an SDP is to be responsible for his own placement, I don’t see how that could be,” Allen said. “If an SDP is locked up for 20 or 30 years he’s out of contact with the free world out there. He doesn’t have any relatives or funds out there to get his own place.”

Allen, still having never faced a criminal trial for his alleged crime, remains in prison today, struggling to find a solution to get out.

Five states in all have laws like Illinois’ Sexually Dangerous Persons Act, that make it possible to civilly commit based on the prospect of them being dangerous.

Three states — Illinois, Massachusetts and North Dakota — and the federal government have it written into their statutes that those people may be held by state departments of corrections, meaning they get their treatment in prison. Across the country, that amounts to hundreds of people like Allen doing hard time without convictions or criminal trials.

This is part of a collaboration with The FRONTLINE Dispatch, a podcast from

PBS FRONTLINE.