The Tremayne Graham Story

The daughter of Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin is being investigated by federal authorities to determine if she helped to launder drug money for her ex-husband.

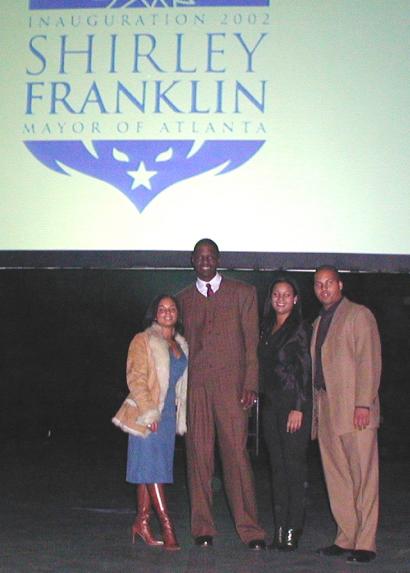

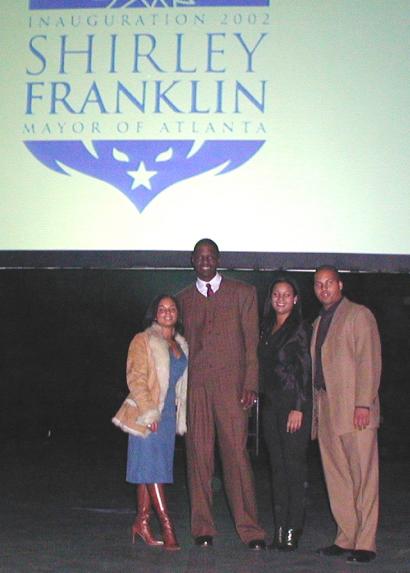

The allegations against Kai Franklin came to light during an April 17 hearing in U.S. District Court in Greenville, S.C., where a judge sentenced Franklin's ex-husband, Tremayne Graham (pictured above), to life in prison for his involvement in a large drug dealing operation.

Kai Franklin, 34, oversaw tens of thousands of dollars from cocaine sales in 2004 and 2005, according to court records and testimony reported by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Graham, 33, admitted his role in shipping at least 1,000 kilograms of Mexican cocaine from Los Angeles to Atlanta and South Carolina.

According to testimony from his co-defendant, Franklin twice received bags of drug money-one containing $25,000, the other $20,000 - at the direction of Graham. In addition, another co-defendant said Franklin received portions of $150,000 in drug money invested in an airport concessions company run by her father, David Franklin, the mayor's former husband.

The Feds say they’ve established a money trail that links several cash transfers from Graham to Franklin in the seven months he was a fugitive. Franklin divorced Graham in 2005.

So far, no charges have been filed against Franklin.

*Our favorite writer Mara Shalhoup @ Creative Loafing.com takes you inside Tremayne Graham's empire.

The following excerpts are from her story: "Tremayne Graham: Drugs, Murder & Deceit: The Mayor's Son-In-Law. To read Shalhoup's entire story, click the following link: Tremayne Graham

ATL KINGPIN (THE MAYOR'S FORMER SON-IN-LAW):

The bounty hunter came recommended as one of the country's finest, and on the afternoon of June 16, 2005, he was within minutes of doing what he does best: taking a dangerous fugitive down.

The location was a Subway sandwich shop in an upscale L.A. neighborhood. The bounty hunter slipped inside to make sure the guy in line was in fact the man he'd been tracking for the past three months. He then gave the signal to a team of U.S. marshals, DEA agents and local cops assembled in the parking lot. As the fugitive walked out, sandwich in hand, he would claim he was someone else. He even had a California driver's license.

But that was a lie. His slender, 6-foot-5 frame, his narrowed eyes and crooked grin, a style of dress more suggestive of a bank executive than a cocaine kingpin – all of it was hard to miss. They had their man.

Tremayne Graham was done.

But the investigation – which eventually would net a mountain of evidence implicating Graham in crimes from cocaine trafficking to murder – was far from over.

There's something about Graham that made people believe in him, to become convinced he was someone he wasn't. He sold $150,000-plus cars in the clublike setting of his Atlanta dealership to the type of people who might qualify for an AmEx black card. Graham even wooed, and later married, a petite, fresh-faced girl and got himself invited to Christmas dinner with her mother, Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin.

Paul and Katie Carter of Fayetteville, N.C., received a terrible call. In the early-morning hours that day, two people had kicked in the door of their daughter's Atlanta townhouse. The men treaded upstairs to her bedroom, where they shot to death the Carters' daughter and her boyfriend. He was one of Tremayne Graham's co-defendants.

BLACK MAFIA FAMILY & SIN CITY MAFIA CONNECTION:

Over the next three years, investigations into the homicides and the cocaine ring would reveal connections between Graham and some of the country's most notorious drug runners. The work of the bounty hunter, federal prosecutors, U.S. marshals, the DEA, the IRS and local law enforcement in Georgia, South Carolina and California revealed that Graham was a major drug dealer. It also would suggest that he devised a near-foolproof plan for moving mass shipments of cocaine across the country; that he worked in concert with the Black Mafia Family and Sin City Mafia, two multistate drug crews with big presences in Atlanta; and that, along with the leader of Sin City (Jerry Davis, above), he orchestrated a brutal crime for which he would later feign fear.

In the early 1990s, Tremayne Graham, then a student at Clemson University, met Scott King, a basketball player from nearby Mars Hill College. Graham ran with a crowd that included Clemson basketball players Andre Bovain and Devin Gray -- both of whom would later be convicted on cocaine charges. Those were the same circles Graham revisited when, after moving to Atlanta, he started shipping large quantities of drugs up to Greenville, S.C.

In Atlanta, Graham happened to bump into King again, while partying at a club. The two eventually hatched a business plan. In 2001, they opened a car dealership and customization shop offering $2,000 rims and $350,000 Bentleys. The walls were graced with autographed jerseys from clients such as Atlanta Brave Andruw Jones and Cleveland Brown Corey Fuller. Graham's business was a portal to celebrities. And his wife, whom he married three months after 404 Motorsports was incorporated, was a liaison to Atlanta's political elite.

Then there were the other major players with whom Graham allegedly hung out – those believed to be among the nation's biggest cocaine kingpins. One was Terry "Southwest T" Flenory, who's currently facing federal cocaine-conspiracy charges for his alleged leadership role in the $270 million cocaine enterprise known as the Black Mafia Family. According to a document filed in federal court in Greenville, "'substantial evidence' links defendant Graham and his co-defendants to the Black Mafia Family."

One former BMF member has described Flenory as a silent investor in 404 Motorsports. The informant recalled to the feds a 2003 meeting between Graham and Flenory, held at a Lithonia mansion dubbed "the White House" – perhaps so-named because the informant claims to have seen as many as 100 kilos of coke stacked in the basement. During one visit, the former BMF member claims, Flenory ordered him to load $250,000 cash into Graham's vehicle, which was outfitted with secret compartments.

Then there's Sin City Mafia. While BMF – an early version of it, anyway – arrived in Atlanta in the '90s by way of Detroit, Sin City came up out of Phenix City, Ala., just across the Georgia line. Its alleged leader, Jerry "J-Rock" Davis, is believed to have moved an amount of cocaine on par with the Flenory brothers, meaning tens of thousands of kilos in less than a decade.

While BMF was referred to in the Sin City camp as "the other side," members of the two crews appeared to be tight. Davis' wife was believed to have laundered money for BMF, and both crews are alleged to have worked together to move drugs across the country. Members of BMF and Sin City hung out at the same houses, including a storied party pad in Dunwoody. The Flenory brothers' father, Charles, or "Pops," helped Davis with some renovation work at his Westside recording studio, Platinum Recordings. And in May 2005, when a high-ranking BMF member found himself surrounded by federal marshals, he made a distress call to Sin City's Davis. Investigators believe Davis responded by sending someone to fire on the marshals gathered outside the house where the BMF member was being apprehended.

Tremayne Graham's links to Davis and the Sin City crew were even more pronounced than his ties to BMF. Court records would claim – and Graham would confirm to the feds – that Davis supplied him with the cocaine he and King sent up I-85 to smaller dealers in Greenville. Graham also is credited with devising a plan that Davis used to ship his cocaine from California, where it was imported from Mexico, to Atlanta.

"Graham's method," a confidential informant told the feds, was "designed to protect all of the participants, by allowing them to claim ignorance if they were caught with the drugs." The coke was packed in boxes and coolers and shipped to a fake Atlanta address. The informant claimed on one occasion to have met with both Graham and Davis to pick up a half-dozen boxes at one of Davis' California homes. (Davis owned at least three of them, which allegedly were referred to in Sin City circles as "first," "second" and "third" base.)

Graham had told the informant to wear conservative clothing, and he helped load the 70-pound boxes into a van. Graham then instructed the informant to drive the van to a nearby UPS store and send the packages off. The informant claimed Graham had a guy in an Atlanta UPS office who intercepted all shipments sent to the fake address and hand-delivered them to Graham and his crew. Davis paid Graham $60,000 for overseeing each multibox shipment, according to the informant.

Once, when the informant shipped some boxes belonging not to Davis but to his alleged right-hand man, a former BMF associate named Richard Garrett, a darker side of Davis allegedly emerged. The shipment was confiscated by authorities, according to a court document, and Davis confronted the informant; he said that if the shipment had belonged to him rather than Garrett, the informant "would be dead."

Davis wasn't the type of guy people wanted to cross. Which is why, when the feds began to make inroads into the Sin City organization, they only got as far as King and Graham. At least at first.

In late 2002, Greenville police and the DEA launched an investigation into a local cocaine dealer named Barron Johnson. Within a year, they had a wire up on Johnson's phone. Agents listening in learned that Johnson was getting his coke from Atlanta -- from a supplier named Scott King.

Johnson and King, along with several of Johnson's Greenville associates, were indicted, under seal, in December 2003. Johnson was quickly apprehended. It didn't take long for investigators to convince him to talk. He even arranged a four-kilo shipment from King, who didn't know about the Johnson arrest or his own pending federal charges. King sent one of his guys to Greenville, as he'd done countless times before.

On Jan. 21, 2004, King's courier, Ulysses Hackett, arrived at a stash house King used, on Greenville's Singing Pines Drive. The police were waiting. And Hackett, his vehicle packed with the coke in an electronically operated secret compartment, was promptly arrested.

In addition to the four kilos Johnson had ordered, investigators found another 10 kilos in the stash house. The drugs, along with $80,000, were stored in five underground safes. Investigators were able to track down the Atlanta locksmith who'd done the work, and the locksmith said he'd been hired by a guy named Tremayne Graham. Graham's name also was on the lease for the house. And investigators connected Graham to King through 404 Motorsports.

After the killings of Graham's co-defendant and his girlfriend, Graham -- who was still out on bond and under house arrest -- moved into his mother-in-law's house, King would claim. He said Graham wanted to give the appearance that, by staying with the mayor, he was scared for his life.

But any semblance of Graham's propriety disappeared when, less than two months after the double homicide and a few days before his trial was set to start, Graham skipped town.

In the seven months he was a fugitive, his wife would divorce him on the grounds that he'd abandoned her, leaving her in massive debt. According to divorce and bankruptcy papers filed by Kai Franklin Graham in early 2005, her husband had burdened her with the $347,000 balance of the bond he'd jumped and the $5,000 monthly mortgage on their sprawling Marietta home. And he'd taken most of the couple's cash and valuables, including almost all of the diamond jewelry, with him. His wife, unemployed and, according to her bankruptcy documents, nearly penniless, was getting by on about $2,000 per month from her mother, her father (the mayor's ex-husband), and her siblings.

The company that had bonded out Graham was desperate to recover the money his near-bankrupt wife was incapable of paying.

Mayor Shirley Franklin has had nothing to say publicly about Graham since she expressed hope for his innocence two years ago.

Shortly after the April sentencing hearing (where Graham was sentenced to life in prison), Mayor Franklin did issue a more general statement:

"While I have no knowledge of the details of the case or its proceedings, I find the sale and use of illegal drugs abhorrent," the mayor wrote. "I have long believed and there is more than enough evidence that illegal drugs, guns and violence have been destructive to the very fabric of American life. My contempt personally and professionally for the devastation that drugs and violence has caused in our community has not changed."

The daughter of Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin is being investigated by federal authorities to determine if she helped to launder drug money for her ex-husband.

The allegations against Kai Franklin came to light during an April 17 hearing in U.S. District Court in Greenville, S.C., where a judge sentenced Franklin's ex-husband, Tremayne Graham (pictured above), to life in prison for his involvement in a large drug dealing operation.

Kai Franklin, 34, oversaw tens of thousands of dollars from cocaine sales in 2004 and 2005, according to court records and testimony reported by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Graham, 33, admitted his role in shipping at least 1,000 kilograms of Mexican cocaine from Los Angeles to Atlanta and South Carolina.

According to testimony from his co-defendant, Franklin twice received bags of drug money-one containing $25,000, the other $20,000 - at the direction of Graham. In addition, another co-defendant said Franklin received portions of $150,000 in drug money invested in an airport concessions company run by her father, David Franklin, the mayor's former husband.

The Feds say they’ve established a money trail that links several cash transfers from Graham to Franklin in the seven months he was a fugitive. Franklin divorced Graham in 2005.

So far, no charges have been filed against Franklin.

*Our favorite writer Mara Shalhoup @ Creative Loafing.com takes you inside Tremayne Graham's empire.

The following excerpts are from her story: "Tremayne Graham: Drugs, Murder & Deceit: The Mayor's Son-In-Law. To read Shalhoup's entire story, click the following link: Tremayne Graham

ATL KINGPIN (THE MAYOR'S FORMER SON-IN-LAW):

The bounty hunter came recommended as one of the country's finest, and on the afternoon of June 16, 2005, he was within minutes of doing what he does best: taking a dangerous fugitive down.

The location was a Subway sandwich shop in an upscale L.A. neighborhood. The bounty hunter slipped inside to make sure the guy in line was in fact the man he'd been tracking for the past three months. He then gave the signal to a team of U.S. marshals, DEA agents and local cops assembled in the parking lot. As the fugitive walked out, sandwich in hand, he would claim he was someone else. He even had a California driver's license.

But that was a lie. His slender, 6-foot-5 frame, his narrowed eyes and crooked grin, a style of dress more suggestive of a bank executive than a cocaine kingpin – all of it was hard to miss. They had their man.

Tremayne Graham was done.

But the investigation – which eventually would net a mountain of evidence implicating Graham in crimes from cocaine trafficking to murder – was far from over.

There's something about Graham that made people believe in him, to become convinced he was someone he wasn't. He sold $150,000-plus cars in the clublike setting of his Atlanta dealership to the type of people who might qualify for an AmEx black card. Graham even wooed, and later married, a petite, fresh-faced girl and got himself invited to Christmas dinner with her mother, Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin.

Paul and Katie Carter of Fayetteville, N.C., received a terrible call. In the early-morning hours that day, two people had kicked in the door of their daughter's Atlanta townhouse. The men treaded upstairs to her bedroom, where they shot to death the Carters' daughter and her boyfriend. He was one of Tremayne Graham's co-defendants.

BLACK MAFIA FAMILY & SIN CITY MAFIA CONNECTION:

Over the next three years, investigations into the homicides and the cocaine ring would reveal connections between Graham and some of the country's most notorious drug runners. The work of the bounty hunter, federal prosecutors, U.S. marshals, the DEA, the IRS and local law enforcement in Georgia, South Carolina and California revealed that Graham was a major drug dealer. It also would suggest that he devised a near-foolproof plan for moving mass shipments of cocaine across the country; that he worked in concert with the Black Mafia Family and Sin City Mafia, two multistate drug crews with big presences in Atlanta; and that, along with the leader of Sin City (Jerry Davis, above), he orchestrated a brutal crime for which he would later feign fear.

In the early 1990s, Tremayne Graham, then a student at Clemson University, met Scott King, a basketball player from nearby Mars Hill College. Graham ran with a crowd that included Clemson basketball players Andre Bovain and Devin Gray -- both of whom would later be convicted on cocaine charges. Those were the same circles Graham revisited when, after moving to Atlanta, he started shipping large quantities of drugs up to Greenville, S.C.

In Atlanta, Graham happened to bump into King again, while partying at a club. The two eventually hatched a business plan. In 2001, they opened a car dealership and customization shop offering $2,000 rims and $350,000 Bentleys. The walls were graced with autographed jerseys from clients such as Atlanta Brave Andruw Jones and Cleveland Brown Corey Fuller. Graham's business was a portal to celebrities. And his wife, whom he married three months after 404 Motorsports was incorporated, was a liaison to Atlanta's political elite.

Then there were the other major players with whom Graham allegedly hung out – those believed to be among the nation's biggest cocaine kingpins. One was Terry "Southwest T" Flenory, who's currently facing federal cocaine-conspiracy charges for his alleged leadership role in the $270 million cocaine enterprise known as the Black Mafia Family. According to a document filed in federal court in Greenville, "'substantial evidence' links defendant Graham and his co-defendants to the Black Mafia Family."

One former BMF member has described Flenory as a silent investor in 404 Motorsports. The informant recalled to the feds a 2003 meeting between Graham and Flenory, held at a Lithonia mansion dubbed "the White House" – perhaps so-named because the informant claims to have seen as many as 100 kilos of coke stacked in the basement. During one visit, the former BMF member claims, Flenory ordered him to load $250,000 cash into Graham's vehicle, which was outfitted with secret compartments.

Then there's Sin City Mafia. While BMF – an early version of it, anyway – arrived in Atlanta in the '90s by way of Detroit, Sin City came up out of Phenix City, Ala., just across the Georgia line. Its alleged leader, Jerry "J-Rock" Davis, is believed to have moved an amount of cocaine on par with the Flenory brothers, meaning tens of thousands of kilos in less than a decade.

While BMF was referred to in the Sin City camp as "the other side," members of the two crews appeared to be tight. Davis' wife was believed to have laundered money for BMF, and both crews are alleged to have worked together to move drugs across the country. Members of BMF and Sin City hung out at the same houses, including a storied party pad in Dunwoody. The Flenory brothers' father, Charles, or "Pops," helped Davis with some renovation work at his Westside recording studio, Platinum Recordings. And in May 2005, when a high-ranking BMF member found himself surrounded by federal marshals, he made a distress call to Sin City's Davis. Investigators believe Davis responded by sending someone to fire on the marshals gathered outside the house where the BMF member was being apprehended.

Tremayne Graham's links to Davis and the Sin City crew were even more pronounced than his ties to BMF. Court records would claim – and Graham would confirm to the feds – that Davis supplied him with the cocaine he and King sent up I-85 to smaller dealers in Greenville. Graham also is credited with devising a plan that Davis used to ship his cocaine from California, where it was imported from Mexico, to Atlanta.

"Graham's method," a confidential informant told the feds, was "designed to protect all of the participants, by allowing them to claim ignorance if they were caught with the drugs." The coke was packed in boxes and coolers and shipped to a fake Atlanta address. The informant claimed on one occasion to have met with both Graham and Davis to pick up a half-dozen boxes at one of Davis' California homes. (Davis owned at least three of them, which allegedly were referred to in Sin City circles as "first," "second" and "third" base.)

Graham had told the informant to wear conservative clothing, and he helped load the 70-pound boxes into a van. Graham then instructed the informant to drive the van to a nearby UPS store and send the packages off. The informant claimed Graham had a guy in an Atlanta UPS office who intercepted all shipments sent to the fake address and hand-delivered them to Graham and his crew. Davis paid Graham $60,000 for overseeing each multibox shipment, according to the informant.

Once, when the informant shipped some boxes belonging not to Davis but to his alleged right-hand man, a former BMF associate named Richard Garrett, a darker side of Davis allegedly emerged. The shipment was confiscated by authorities, according to a court document, and Davis confronted the informant; he said that if the shipment had belonged to him rather than Garrett, the informant "would be dead."

Davis wasn't the type of guy people wanted to cross. Which is why, when the feds began to make inroads into the Sin City organization, they only got as far as King and Graham. At least at first.

In late 2002, Greenville police and the DEA launched an investigation into a local cocaine dealer named Barron Johnson. Within a year, they had a wire up on Johnson's phone. Agents listening in learned that Johnson was getting his coke from Atlanta -- from a supplier named Scott King.

Johnson and King, along with several of Johnson's Greenville associates, were indicted, under seal, in December 2003. Johnson was quickly apprehended. It didn't take long for investigators to convince him to talk. He even arranged a four-kilo shipment from King, who didn't know about the Johnson arrest or his own pending federal charges. King sent one of his guys to Greenville, as he'd done countless times before.

On Jan. 21, 2004, King's courier, Ulysses Hackett, arrived at a stash house King used, on Greenville's Singing Pines Drive. The police were waiting. And Hackett, his vehicle packed with the coke in an electronically operated secret compartment, was promptly arrested.

In addition to the four kilos Johnson had ordered, investigators found another 10 kilos in the stash house. The drugs, along with $80,000, were stored in five underground safes. Investigators were able to track down the Atlanta locksmith who'd done the work, and the locksmith said he'd been hired by a guy named Tremayne Graham. Graham's name also was on the lease for the house. And investigators connected Graham to King through 404 Motorsports.

After the killings of Graham's co-defendant and his girlfriend, Graham -- who was still out on bond and under house arrest -- moved into his mother-in-law's house, King would claim. He said Graham wanted to give the appearance that, by staying with the mayor, he was scared for his life.

But any semblance of Graham's propriety disappeared when, less than two months after the double homicide and a few days before his trial was set to start, Graham skipped town.

In the seven months he was a fugitive, his wife would divorce him on the grounds that he'd abandoned her, leaving her in massive debt. According to divorce and bankruptcy papers filed by Kai Franklin Graham in early 2005, her husband had burdened her with the $347,000 balance of the bond he'd jumped and the $5,000 monthly mortgage on their sprawling Marietta home. And he'd taken most of the couple's cash and valuables, including almost all of the diamond jewelry, with him. His wife, unemployed and, according to her bankruptcy documents, nearly penniless, was getting by on about $2,000 per month from her mother, her father (the mayor's ex-husband), and her siblings.

The company that had bonded out Graham was desperate to recover the money his near-bankrupt wife was incapable of paying.

Mayor Shirley Franklin has had nothing to say publicly about Graham since she expressed hope for his innocence two years ago.

Shortly after the April sentencing hearing (where Graham was sentenced to life in prison), Mayor Franklin did issue a more general statement:

"While I have no knowledge of the details of the case or its proceedings, I find the sale and use of illegal drugs abhorrent," the mayor wrote. "I have long believed and there is more than enough evidence that illegal drugs, guns and violence have been destructive to the very fabric of American life. My contempt personally and professionally for the devastation that drugs and violence has caused in our community has not changed."

Clemson low key be putting out some brehs who excel in the streets. The neighborhood superstar dude who had that work in my area growing up went to Clemson too, no sports ride either. Just a regular college breh. Most of the more succesful dope boys I knew went to some type of college actually. That shyt about dudes who excel in the streets being dumbasses or just street smart and no book smarts is a myth. shyt me myself, I found my love for reading when I was in boot camp. And I wasn't reading no Iceberg Slim or Donald Goines either, I stayed with my head in a history or science book.

Clemson low key be putting out some brehs who excel in the streets. The neighborhood superstar dude who had that work in my area growing up went to Clemson too, no sports ride either. Just a regular college breh. Most of the more succesful dope boys I knew went to some type of college actually. That shyt about dudes who excel in the streets being dumbasses or just street smart and no book smarts is a myth. shyt me myself, I found my love for reading when I was in boot camp. And I wasn't reading no Iceberg Slim or Donald Goines either, I stayed with my head in a history or science book.