Election of 1898

In 1871 Democrats regained control of the state legislature.

After 1875, the white Democratic campaign to reduce voting by freedmen was helped by the

Red Shirts, a

paramilitary group that openly disrupted Republican and especially black meetings, and intimidated voters to keep them from the polls. The group had started in Mississippi in 1875, and chapters arose in both the Carolinas. In the same period, some 20,000 white men in North Carolina belonged to rifle clubs, who comprised other paramilitary groups. Although Democrats dominated state politics after 1877, both blacks and whites continued to participate in politics and, in the 1890s, the

Populists appealed to many former Democratic voters. The last black US Congressman of the 19th century from North Carolina was elected in 1896; another African-American congressman was not elected from the state until the late 20th century, due to disfranchisement of blacks in 1899.

In the 1894 and 1896 elections, North Carolina's Populist Party supported fusion candidates in an alliance with the Republican Party; they won enough votes to gain control of the state government; they were known as the Fusionists. Governor

Daniel L. Russell, a Republican was elected in 1896. The Fusionists won the elections and passed a law increasing the franchise for blacks and whites, who were the majority in the state, by decreasing property requirements for voters. Russell was the first Republican elected since 1877.

During the 1898 election, the Democratic Party regained control at the state level, in part due to widespread violence and intimidation of blacks by the Red Shirts, which suppressed black voting. They ran a campaign of regaining white supremacy. Russell was unable to satisfy both the Populist and Republican parties to keep the Fusion coalition viable.

[6]

Because Wilmington was a black-majority city, its election of city officers was followed statewide. Groups of four to eight white men had been patrolling every block in the city for weeks before the election.

[7] On November 4, 1898, the

Raleigh News & Observer noted that,

The first Red Shirt parade on horseback ever witnessed in

Wilmington electrified the people today. It created enthusiasm among the whites and consternation among the Negroes. The whole town turned out to see it. It was an enthusiastic body of men. Otherwise it was quiet and orderly.

Despite the Democrats' inflammatory rhetoric in support of

white supremacy, and the Red Shirt armed display, voters elected a biracial fusionist government to office in Wilmington on November 8; the mayor and 2/3 of the aldermen were white.

Democratic Party white supremacists, led by

Alfred Moore Waddell, who as incumbent had lost his congressional seat to

Daniel L. Russell (now governor) in 1878, had organized a secret committee of nine. This committee had planned to replace the government if the Democratic Party candidates lost. During the election campaign, whites had criticized

Alexander Manly, owner and editor of Wilmington's

Daily Record, the state's only black-owned newspaper, and wanted to close him down.

For some time,

Josephus Daniels, editor of the Raleigh

News and Observer, had used Wilmington as a symbol for "Negro domination" because of its government, although it was biracial and dominated by a two-thirds white majority. Many newspapers published pictures and stories implying that African-American men were sexually attacking white women in the city. Manly denied such charges, saying the stories represented consensual relationships and suggested "white men [should] be more protective of their women against sexual advances from males of all races."

[8] White supremacists publicized his words as a catalyst for violence against the black community.

[8]

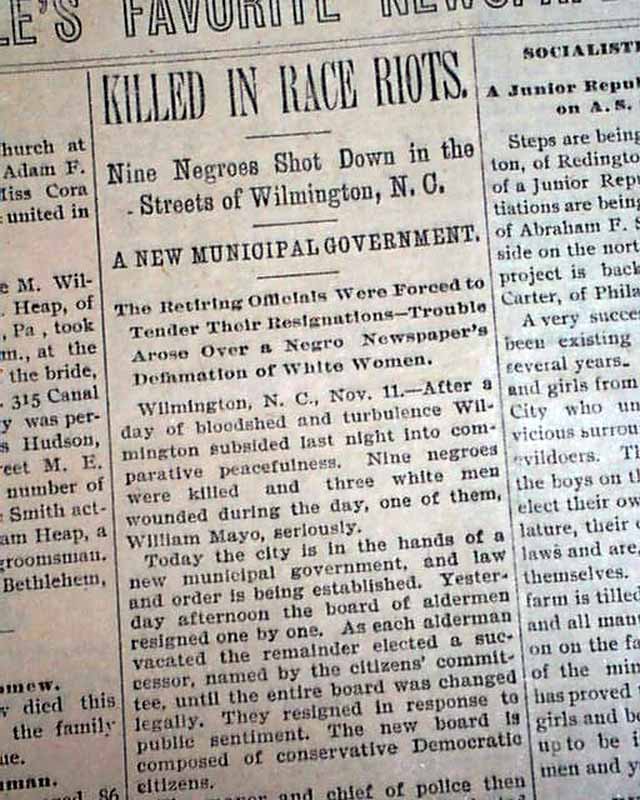

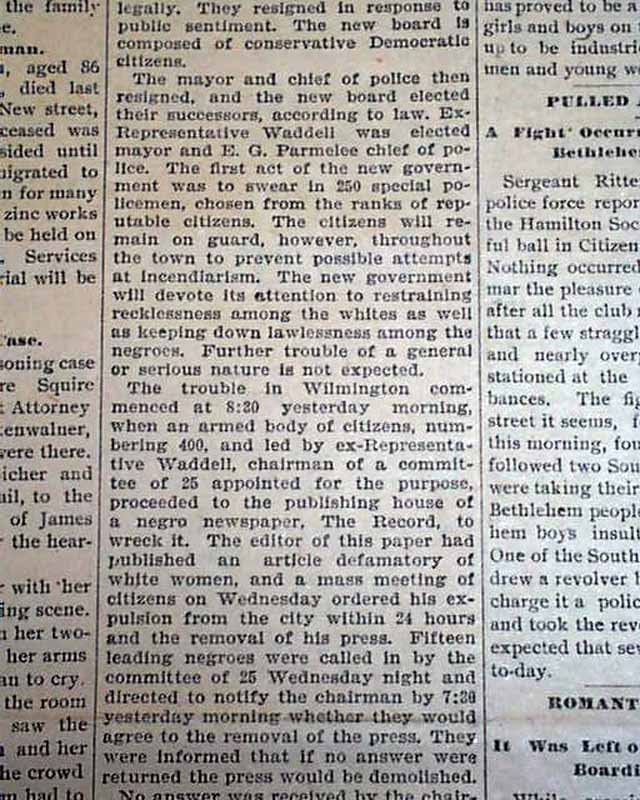

After the election, whites created a Committee of Twenty-Five, all supremacists, and presented their demands to the Committee of Colored Citizens (CCC), a group of politicians and leaders of the African-American community. Specifically, the whites wanted the CCC to promise to evict Manly and his brother Frank, a co-owner of the paper, from the city. They gave the CCC a deadline of November 10, 1898 to respond. When Waddell and the Committee had not received a response by 7:30 a.m., he gathered a large group of white businessmen and veterans at the Wilmington Light Infantry (WLI) armory.

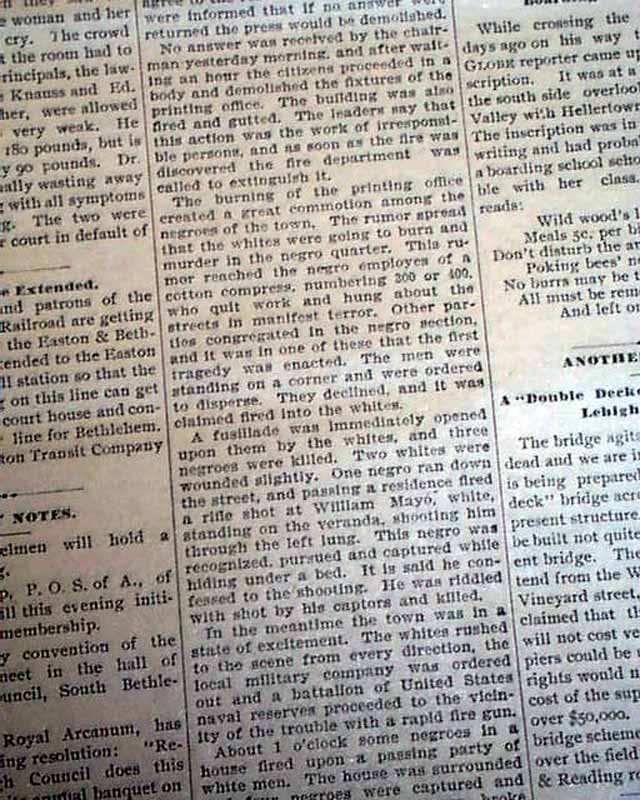

[4] By 8:00 a.m., Waddell led the armed group of 1,000-1500 men, organized in military formation, to the

Daily Record office, where they destroyed the equipment and burned down the building of the only African-American newspaper in the state. By this time, the crowd had swelled to nearly 2,000 men.

[7]

By this time, Manly, along with many others, had hidden or fled Wilmington for safety. Waddell tried to get the group to return to the Armory and disband, but he lost control, and the armed men turned into a mob. Whites rioted and shot guns, attacking blacks throughout Wilmington but especially in Brooklyn, the majority-black neighborhood.[7] The small patrols were spread out over the city and continued until nightfall. Walker Taylor, of the Secret Nine, was authorized by Governor Russell to command the Wilmington Light Infantry (WLI) troops, newly returned from the Spanish–American War, and the federal Naval Reserves, taking them into Brooklyn to quell the "riot". They intimidated both black and white crowds with rapid-fire weapons, but the WLI killed several black men.[7]

Whites drove the opposing political and business leaders from the town. The estimated number of deaths ranges from six to 100, all blacks. Because of incomplete records by the hospital, churches and coroner's office, the number of people killed remains uncertain, but no whites were reported dead. Some whites were wounded.

Hundreds of blacks fled the town to take shelter in nearby swamps. After the violence settled, more than 2100 blacks left Wilmington permanently, hollowing out its professional and artisan class and changing the demographics to leave a white majority city.[4]

Waddell and his mob forced the white Republican Mayor Silas P. Wright and other members of the city government (both black and white) to resign. (Their terms would have lasted until 1899). They installed a new city council that elected Waddell to take over as mayor by 4 p.m. that day.

[7]

City residents' appeals to President

William McKinley for help to recover from the widespread destruction in Brooklyn were met with no response.

Subsequent to Waddell's usurping power, he and his team were elected in March 1899 to city offices. More importantly, that year, the Democratic-dominated state legislators (see

North Carolina General Assembly of 1899-1900) passed a constitutional amendment in 1899 to exclude black voters: it required voters to pay a

poll tax and pass a

literacy test (administered by whites) to register to vote, both measures that in practice discriminated against blacks and poor whites. When Democrats had first proposed the measure in 1881,

The New York Times estimated that 40,000 black men would be

disfranchised by such action in North Carolina. The legislators infringed on the constitutional right to vote, but the

US Supreme Court had recently upheld similar measures in a challenge to Mississippi's 1890 constitution. Democrats in other southern states also worked to reduce the black vote, passing disfranchising laws or constitutions following Mississippi's and through 1908.

Once that was done, Democrats passed laws imposing racial segregation of public facilities and

Jim Crow. They essentially imposed martial law on African Americans in North Carolina, setting an example that had influence beyond the state's borders. Not until the gains of

African-American Civil Rights Movement and after passage of federal laws in the mid-1960s several generations later would most African Americans regain their civil rights in North Carolina and other Southern states.

Hugh MacRae was among the nine conspirators who planned the insurrection. He later donated land outside Wilmington to

New Hanover County for a park, which was named for him. In the park stands a plaque in his honor that does not mention his role in the 1898 insurrection. A descendant of his contributed to the 1998 centennial commemoration

to every last one of those demons.

to every last one of those demons.