Inside the Phone Company Secretly Run By Drug Traffickers

Crime blogger Martin Kok was assassinated while leaving a sex club. It turned out MPC, one of his clients, was not an ordinary phone company.

by Joseph Cox

Oct 22 2019, 9:44am

ShareTweet

Snap

Image: Cathryn Virginia

Martin Kok had already dodged death once that day. As the 49-year-old Dutch convict turned successful crime blogger left a late lunch at an Amsterdam hotel in December 2016, a hooded man ran up to him, aimed a handgun at point blank range at the back of his head, and prepared to pull the trigger.

But either the assassin lost his nerve or the weapon jammed. CCTV footage later revealed the man ran off across the street, nearly getting hit by two cyclists, and disappeared into the city. Kok continued walking, oblivious.

Kok had enemies. On his website Butterfly Crime, Kok covered everyone from biker gangs to Moroccan drug lords. Kok was a killer himself, having been convicted of two murders. But after his life of crime, he focused on writing about the criminal underground, repercussions be damned. Someone had previously placed a bomb under his car that, according to a video made by the Dutch police, was as powerful as 40 hand grenades. He escaped that attempt on his life as well—he found the bomb before it exploded.

After leaving the hotel, Kok met with an associate named Christopher Hughes, known as "Scotty" for his heavy Scottish accent. Hughes worked for MPC, a company that made special, encrypted phones. MPC marketed these devices to the privacy-conscious, even using black and white portraits of Edward Snowden in advertisements. MPC was sponsoring Butterfly Crime, posting ads and flaunting MPC-branded hats and other memorabilia on the site and its social media. For Kok, it was easy money.

"MPC phone delivers multiple levels of encryption over a closed secure network," one tweeted advert from the company reads.

Hughes and Kok spent the evening in Boccacio, a sex club on the outskirts of Amsterdam. After their session, and as the puffer-jacket wearing Kok stepped into a Volkswagen Polo, a hooded figure jumped from the dense shrubbery around the parking lot and fired into the Polo, killing Kok. Hughes walked away from the scene, according to CCTV footage previously published by the Dutch police.

MPC, it turned out, was not an ordinary phone company.

AN UNDERGROUND TRADE

All over the world, in Dutch clubs like the one Kok frequented, or Australian biker hangouts and Mexican drug safe houses, there is an underground trade of custom-engineered phones. These phones typically run software for sending encrypted emails or messages, and use their own server infrastructure for routing communications.

Sometimes the devices have the microphone, camera, and GPS functionality removed. Some also have a dual-boot mode, where powering on the device as normal will show an innocuous menu screen with no sensitive information. But if certain buttons are held down when turning the phone on, it will reveal a secret file system containing the user’s encrypted text messages and other communications.

With these tweaks, the ordinary methods for law enforcement to intercept messages are cut-off—police can’t simply get an ordinary phone tap or subpoena messages from a company; the texts are typically only available in a readable form on the users’ devices.

A handful of these so-called "encrypted phone" companies exist. Many of them cater and sell to criminals. As Kok, the murdered blogger, wrote on his website in 2015, “I see on various crime sites these things [encrypted phones] are offered for sale because many of their future clients are also criminals. Advertising on a site where bicycles are offered does not make sense for this type of company.”

Do you know anything else about MPC or the encrypted phone industry? We'd love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, Wickr on josephcox, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

A British hitman, who prosecutors finally convicted thanks to location data from his fitness device, used an encrypted phone made by a firm called Encrochat. Police found an encrypted BlackBerry when investigating a massive criminal cannabis operation in New York. Phantom Secure sold its devices to members of the infamous Sinaloa Mexican drug cartel, according to the complaint filed against Vincent Ramos, the company’s creator. At the time a source added that Phantom Secure devices have been sold in Mexico, Cuba, and Venezuela, as well as to the Hells Angels biker gang.

Crucially, in the Phantom Secure case, prosecutors alleged the company was not incidental to a crime, in the same way Apple or Google may be when criminals use their phones, but instead that the phone was deliberately created to help criminal activity. In May, Ramos was sentenced to nine years in prison after he pleaded guilty to running a criminal enterprise that knowingly facilitated drug trafficking through the sale of these phones. (Multiple sources, including a family member that asked to remain anonymous as well as Ramos' lawyer, said Ramos set up the company for legitimate uses initially, before falling into the criminal market.)

For MPC, the process of setting up the devices was relatively simple: MPC would take a Google Nexus 5 or Nexus 5X Android phone, and then add its own security features and operating system, according to social media posts from MPC and a source with knowledge of the process. MPC then created the customer’s messaging accounts, added a data-only SIM card (which MPC paid about £20 a month for), and then sold the phone to the customer at £1,200. Six-month renewals cost £700, the source added. MPC only sold around 5,000 phones, the source said, but that still indicates the business netted the company some £6 million. At one point, a version of MPC's phones also used code from an open-source, security-focused Android fork called CopperheadOS, three sources said.

On its website, the company advertised security-focused laptops, tablets, and GPS tracking devices.

An advert from MPC that the company posted to Twitter. Image: Screenshot.

One day in March 2016, I checked my Twitter DM inbox and found a message from an MPC representative.

"Hi Joseph—I'm wondering if you as an individual can be paid to just [give] your honest opinion on encrypted devices in the market today? Or are you associated with anyone just now that would make that impossible," a direct message from the MPC Twitter account to me, read.

The MPC representative suggested they could provide a device for me to review, and asked if I've ever done similar for companies in this space. I declined to be paid, but said if they wanted me to have a look at their product, they should send some more details over.

"We want to send a device to you also of ours so you can see what it's all about—we have offered one million in pound sterling if anyone can break it and intercept our messages and read them," they wrote in a later message.

MPC never provided me with one of their phones, but the company continued to message me sporadically over the following year. At one point, the representative randomly complained of an alleged informant trying to infiltrate encrypted phone companies, and entrap MPC in a meeting.

"Please be aware of this guy; we believe he is a spook government agent trying to use companies like ours to try and gain credibility," MPC wrote.

Even in an industry that loves to embrace the cloak-and-dagger aesthetic, it's not often a PR person contacts you to alert you to an apparent spy trying to sneak their way into a company. Which naturally raises the question: Who in the world was behind MPC?

*

In 2018, a mysterious source reached out to me over an encrypted messaging program. There was very little chit chat; they cut right to the point and sent links to media reports about gangs trafficking multi-million dollars worth of cocaine.

"To give you an idea, the people behind MPC are mentioned here," the source said.

None of the articles mentioned MPC explicitly, but described how two serious drug and weapons traffickers from Glasgow took refuge in Portugal to escape an exploding gang war while still operating their business.

"For the time being, the crimelords are simply dubbed 'The Brothers,'" one Portugese report , based in part on the work of Scottish news site The Daily Record, read.

None of the articles named The Brothers. My source said their names were James and Barrie Gillespie.

And then in February, police confirmed my source was right. Police announced European arrest warrants against Hughes—the MPC employee who was with Kok as he was murdered—and four others. This included James and Barry Gillespie, the two on-the-run alleged kingpins.

The Brothers ultimately control MPC, according to two sources. The link between MPC and The Brothers and their gang has not been previously reported. The law enforcement operation into The Brothers has now stretched overseas, with 200 officers from Colombia, the FBI, and other agencies trying to track them down, and Scottish police regularly briefing the FBI and DEA.

“Please know this: 'The Brothers' connections are worldwide and are extremely violent,” a person with knowledge of the company said. Motherboard obtained company documents and spoke to multiple sources in the secure phone industry, some of whom have interacted directly with MPC, to build a picture of how The Brothers secured a serious chunk of the organized crime technology market through a campaign of threats, intimidation, and violence.

Motherboard granted several sources in this story anonymity to protect them from retaliation.

A law enforcement official currently investigating The Brothers told Motherboard, "Obviously it's MPC that we're interested in."

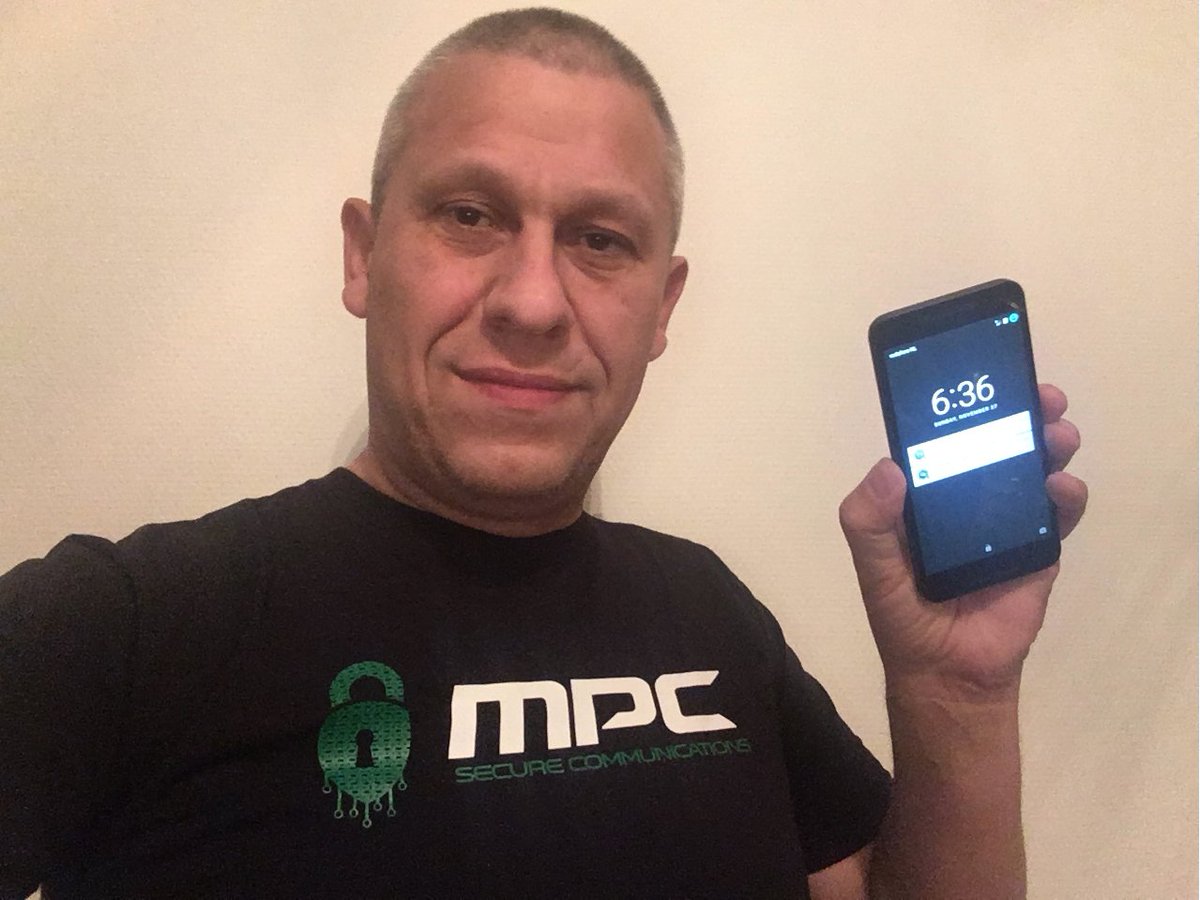

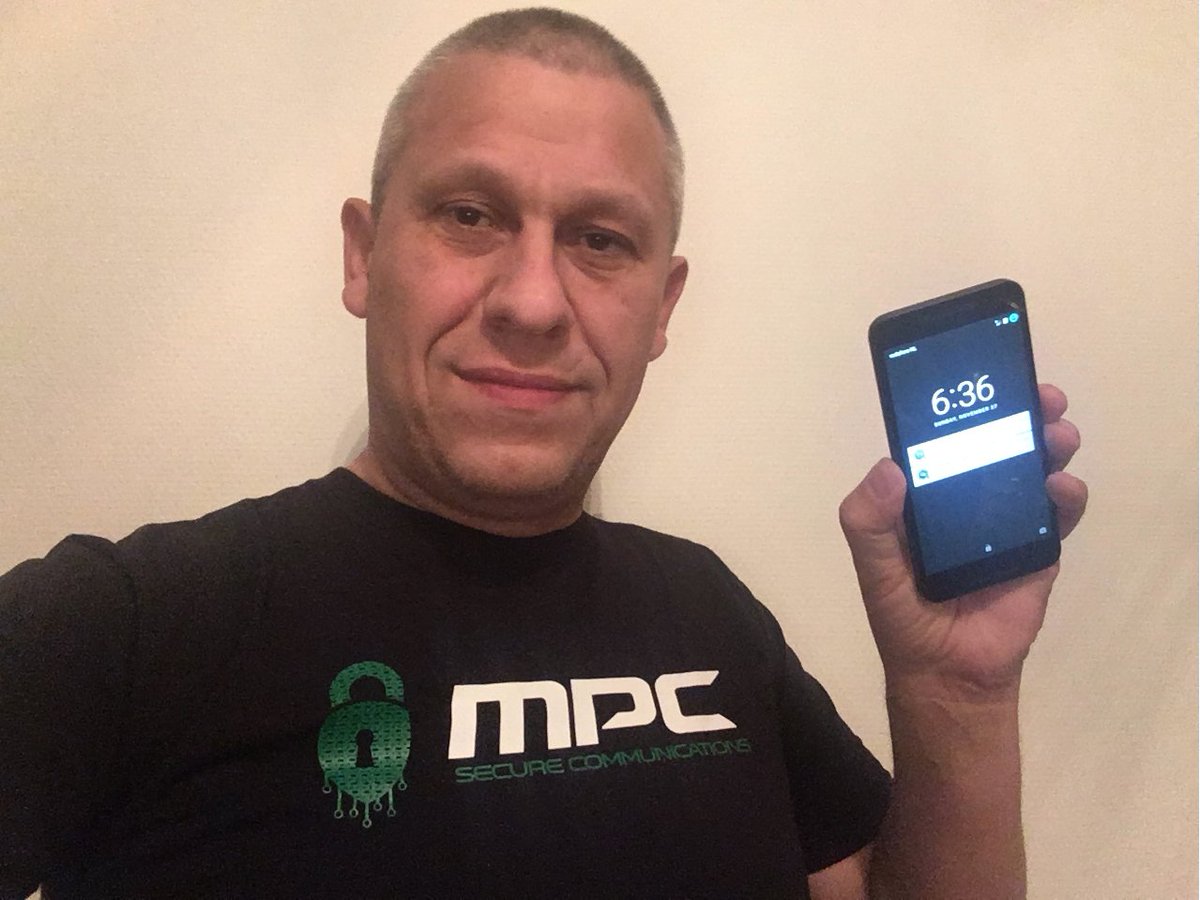

A photo posted to Twitter of murdered crime blogger Martin Kok wearing an MPC branded shirt. Image: Screenshot.

ESCALADE

Dutch investigators believe Kok’s assassination is linked to the so-called Escalade group, a name Scottish law enforcement has given to The Brothers’ criminal enterprise. One Scottish government document described Escalade as “an organized crime case involving the highest level of threat and sophistication in the United Kingdom.”

The group trafficked large quantities of cocaine and heroin from South America into Europe. "I’m told that this group is at the top of the chain of drug transactions in Scotland and the UK as a whole,” Judge Lord Boyd said while sentencing two members in April to seven years each in prison for helping to distribute weapons and drugs.

Several members tortured a man over an unpaid drug debt by tying him up in chains, breaking his arm, shooting him, and pouring bleach in his wounds. An accountant for the gang lied under oath to try and protect one of the torturers. An Escalade associate is wanted in connection with an attack against a former football manager, who was shot in the stomach and face.

Crime blogger Martin Kok was assassinated while leaving a sex club. It turned out MPC, one of his clients, was not an ordinary phone company.

by Joseph Cox

Oct 22 2019, 9:44am

ShareTweet

Snap

Image: Cathryn Virginia

Martin Kok had already dodged death once that day. As the 49-year-old Dutch convict turned successful crime blogger left a late lunch at an Amsterdam hotel in December 2016, a hooded man ran up to him, aimed a handgun at point blank range at the back of his head, and prepared to pull the trigger.

But either the assassin lost his nerve or the weapon jammed. CCTV footage later revealed the man ran off across the street, nearly getting hit by two cyclists, and disappeared into the city. Kok continued walking, oblivious.

Kok had enemies. On his website Butterfly Crime, Kok covered everyone from biker gangs to Moroccan drug lords. Kok was a killer himself, having been convicted of two murders. But after his life of crime, he focused on writing about the criminal underground, repercussions be damned. Someone had previously placed a bomb under his car that, according to a video made by the Dutch police, was as powerful as 40 hand grenades. He escaped that attempt on his life as well—he found the bomb before it exploded.

After leaving the hotel, Kok met with an associate named Christopher Hughes, known as "Scotty" for his heavy Scottish accent. Hughes worked for MPC, a company that made special, encrypted phones. MPC marketed these devices to the privacy-conscious, even using black and white portraits of Edward Snowden in advertisements. MPC was sponsoring Butterfly Crime, posting ads and flaunting MPC-branded hats and other memorabilia on the site and its social media. For Kok, it was easy money.

"MPC phone delivers multiple levels of encryption over a closed secure network," one tweeted advert from the company reads.

Hughes and Kok spent the evening in Boccacio, a sex club on the outskirts of Amsterdam. After their session, and as the puffer-jacket wearing Kok stepped into a Volkswagen Polo, a hooded figure jumped from the dense shrubbery around the parking lot and fired into the Polo, killing Kok. Hughes walked away from the scene, according to CCTV footage previously published by the Dutch police.

MPC, it turned out, was not an ordinary phone company.

AN UNDERGROUND TRADE

All over the world, in Dutch clubs like the one Kok frequented, or Australian biker hangouts and Mexican drug safe houses, there is an underground trade of custom-engineered phones. These phones typically run software for sending encrypted emails or messages, and use their own server infrastructure for routing communications.

Sometimes the devices have the microphone, camera, and GPS functionality removed. Some also have a dual-boot mode, where powering on the device as normal will show an innocuous menu screen with no sensitive information. But if certain buttons are held down when turning the phone on, it will reveal a secret file system containing the user’s encrypted text messages and other communications.

With these tweaks, the ordinary methods for law enforcement to intercept messages are cut-off—police can’t simply get an ordinary phone tap or subpoena messages from a company; the texts are typically only available in a readable form on the users’ devices.

A handful of these so-called "encrypted phone" companies exist. Many of them cater and sell to criminals. As Kok, the murdered blogger, wrote on his website in 2015, “I see on various crime sites these things [encrypted phones] are offered for sale because many of their future clients are also criminals. Advertising on a site where bicycles are offered does not make sense for this type of company.”

Do you know anything else about MPC or the encrypted phone industry? We'd love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, Wickr on josephcox, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

A British hitman, who prosecutors finally convicted thanks to location data from his fitness device, used an encrypted phone made by a firm called Encrochat. Police found an encrypted BlackBerry when investigating a massive criminal cannabis operation in New York. Phantom Secure sold its devices to members of the infamous Sinaloa Mexican drug cartel, according to the complaint filed against Vincent Ramos, the company’s creator. At the time a source added that Phantom Secure devices have been sold in Mexico, Cuba, and Venezuela, as well as to the Hells Angels biker gang.

Crucially, in the Phantom Secure case, prosecutors alleged the company was not incidental to a crime, in the same way Apple or Google may be when criminals use their phones, but instead that the phone was deliberately created to help criminal activity. In May, Ramos was sentenced to nine years in prison after he pleaded guilty to running a criminal enterprise that knowingly facilitated drug trafficking through the sale of these phones. (Multiple sources, including a family member that asked to remain anonymous as well as Ramos' lawyer, said Ramos set up the company for legitimate uses initially, before falling into the criminal market.)

For MPC, the process of setting up the devices was relatively simple: MPC would take a Google Nexus 5 or Nexus 5X Android phone, and then add its own security features and operating system, according to social media posts from MPC and a source with knowledge of the process. MPC then created the customer’s messaging accounts, added a data-only SIM card (which MPC paid about £20 a month for), and then sold the phone to the customer at £1,200. Six-month renewals cost £700, the source added. MPC only sold around 5,000 phones, the source said, but that still indicates the business netted the company some £6 million. At one point, a version of MPC's phones also used code from an open-source, security-focused Android fork called CopperheadOS, three sources said.

On its website, the company advertised security-focused laptops, tablets, and GPS tracking devices.

An advert from MPC that the company posted to Twitter. Image: Screenshot.

One day in March 2016, I checked my Twitter DM inbox and found a message from an MPC representative.

"Hi Joseph—I'm wondering if you as an individual can be paid to just [give] your honest opinion on encrypted devices in the market today? Or are you associated with anyone just now that would make that impossible," a direct message from the MPC Twitter account to me, read.

The MPC representative suggested they could provide a device for me to review, and asked if I've ever done similar for companies in this space. I declined to be paid, but said if they wanted me to have a look at their product, they should send some more details over.

"We want to send a device to you also of ours so you can see what it's all about—we have offered one million in pound sterling if anyone can break it and intercept our messages and read them," they wrote in a later message.

MPC never provided me with one of their phones, but the company continued to message me sporadically over the following year. At one point, the representative randomly complained of an alleged informant trying to infiltrate encrypted phone companies, and entrap MPC in a meeting.

"Please be aware of this guy; we believe he is a spook government agent trying to use companies like ours to try and gain credibility," MPC wrote.

Even in an industry that loves to embrace the cloak-and-dagger aesthetic, it's not often a PR person contacts you to alert you to an apparent spy trying to sneak their way into a company. Which naturally raises the question: Who in the world was behind MPC?

*

In 2018, a mysterious source reached out to me over an encrypted messaging program. There was very little chit chat; they cut right to the point and sent links to media reports about gangs trafficking multi-million dollars worth of cocaine.

"To give you an idea, the people behind MPC are mentioned here," the source said.

None of the articles mentioned MPC explicitly, but described how two serious drug and weapons traffickers from Glasgow took refuge in Portugal to escape an exploding gang war while still operating their business.

"For the time being, the crimelords are simply dubbed 'The Brothers,'" one Portugese report , based in part on the work of Scottish news site The Daily Record, read.

None of the articles named The Brothers. My source said their names were James and Barrie Gillespie.

And then in February, police confirmed my source was right. Police announced European arrest warrants against Hughes—the MPC employee who was with Kok as he was murdered—and four others. This included James and Barry Gillespie, the two on-the-run alleged kingpins.

The Brothers ultimately control MPC, according to two sources. The link between MPC and The Brothers and their gang has not been previously reported. The law enforcement operation into The Brothers has now stretched overseas, with 200 officers from Colombia, the FBI, and other agencies trying to track them down, and Scottish police regularly briefing the FBI and DEA.

“Please know this: 'The Brothers' connections are worldwide and are extremely violent,” a person with knowledge of the company said. Motherboard obtained company documents and spoke to multiple sources in the secure phone industry, some of whom have interacted directly with MPC, to build a picture of how The Brothers secured a serious chunk of the organized crime technology market through a campaign of threats, intimidation, and violence.

Motherboard granted several sources in this story anonymity to protect them from retaliation.

A law enforcement official currently investigating The Brothers told Motherboard, "Obviously it's MPC that we're interested in."

A photo posted to Twitter of murdered crime blogger Martin Kok wearing an MPC branded shirt. Image: Screenshot.

ESCALADE

Dutch investigators believe Kok’s assassination is linked to the so-called Escalade group, a name Scottish law enforcement has given to The Brothers’ criminal enterprise. One Scottish government document described Escalade as “an organized crime case involving the highest level of threat and sophistication in the United Kingdom.”

The group trafficked large quantities of cocaine and heroin from South America into Europe. "I’m told that this group is at the top of the chain of drug transactions in Scotland and the UK as a whole,” Judge Lord Boyd said while sentencing two members in April to seven years each in prison for helping to distribute weapons and drugs.

Several members tortured a man over an unpaid drug debt by tying him up in chains, breaking his arm, shooting him, and pouring bleach in his wounds. An accountant for the gang lied under oath to try and protect one of the torturers. An Escalade associate is wanted in connection with an attack against a former football manager, who was shot in the stomach and face.