"I just wish, like, the comparisons wasn't there," Anthony said. "Because we're totally two different types of players, we was in two different situations...I just wish people would recognize that and understand that."

While Anthony's scoring prowess will almost certainly carry him to the Hall of Fame—he ranks 29th all time in points scored and should crack the top 20 in the next two years—he might get there as part of an

unenviable club: He is tied with Chris Paul, George Gervin and Dominique Wilkins for the most All-Star selections (nine) without a Finals appearance.

Carmelo fans and Carmelo critics will argue until the end of time how much of that failure rests with Anthony and how much rests with the rosters built around him. But everyone wants to see stars evolve, and Anthony is unquestionably moving in the right direction.

"Getting older, you start realizing or figuring out: What other things can I do?" Anthony said. "Realizing the type of system that we're in and how I can take advantage of that system, I don't have to try to score to be effective...I'm more kind of aware and willing to do it, more now, and say, 'OK, I'll sacrifice kind of my own scoring and abilities.'"

The calendar is providing some urgency, with Anthony reaching his 32nd birthday in May. The knee surgery that ended his season last year made a mark, too—"having all that time to myself and figure things out," he said. "I've realized how I can implement myself into the game in much better ways."

There's the evolution everyone wanted. The selfless vision. The team game. The growth mindset.

"It's tough to get there," he said, repeating the thought. "It's tough to get there. And there's only a certain few people who can relate to that."

EIGHT MONTHS BEFORE their bonding session on a hotel staircase, two gifted athletes attended a USA Basketball development camp in Colorado Springs, Colorado. They crossed paths only briefly, but long enough to leave a lasting impression.

"I saw his physicality," Anthony said of James. "I fell in love with his game right then and there."

"A little skinny kid out of Baltimore, braids in his hair," James said of Anthony. "I just remember coming back home and telling my high school friends, 'Man, I played against one of the best guys I ever played in my life so far.'"

Anthony was only there for a day, but James quickly took note of his rare combination of size, strength, ball-handling and shooting skills. He reminded James of Lamar Odom and Scottie Pippen.

James saw something else, too: a certain buoyancy in the kid's gait, a shimmy across the shoulders as Anthony moved upcourt.

"Like a Slinky," James said, smiling and mimicking the movement. "He's got that East Coast game, that Baltimore in him, man…It's just a

bounce how Melo plays."

Neither player had ever seen anyone quite like the other.

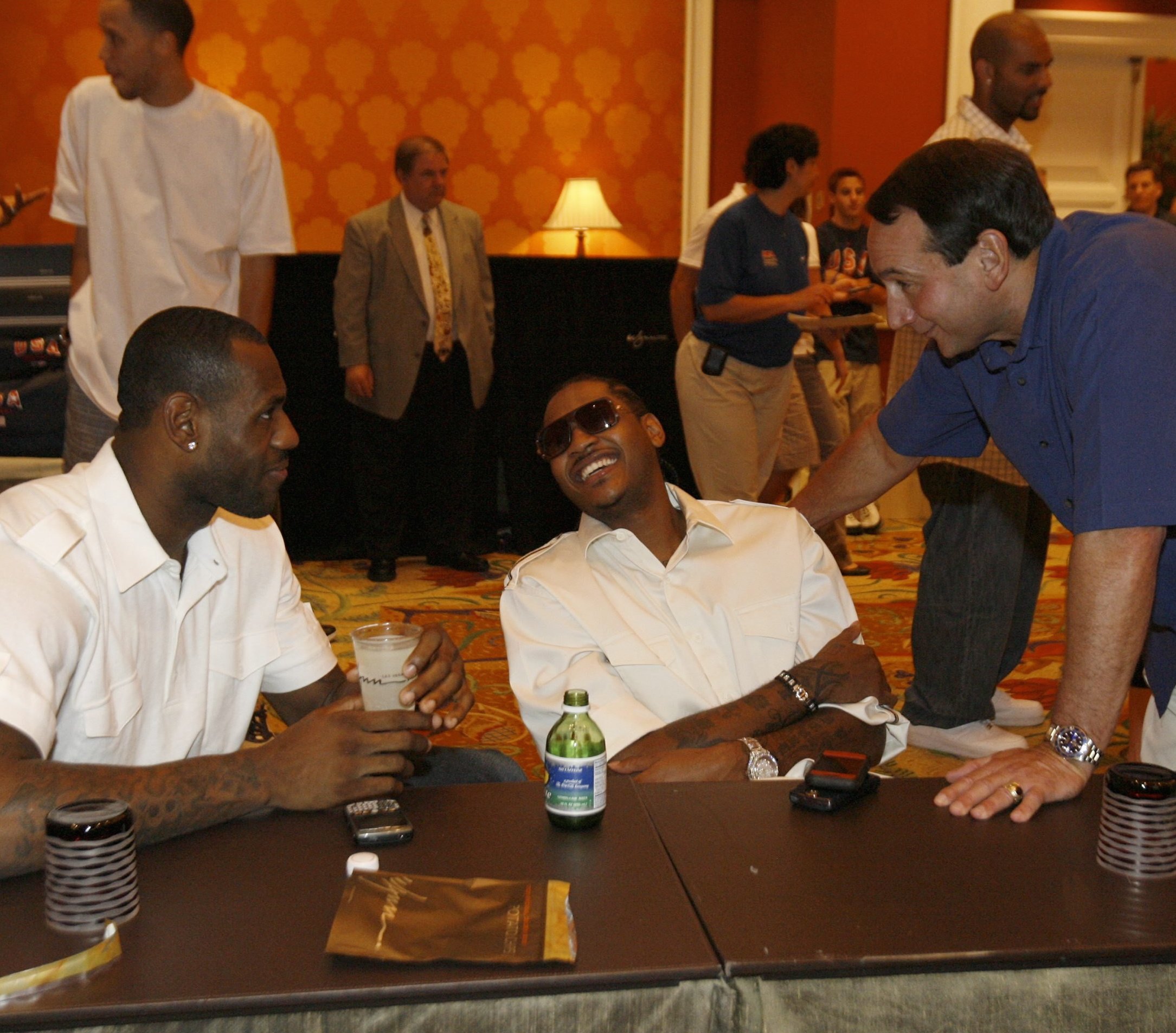

James and Anthony chat while waiting to play in Magic Johnson's 'A Midsummer Night's Magic' charity game the summer after both were drafted. (Photo: Andrew D. Bernstein/Getty Images)

"He wanted to pass the ball more than he wanted to ever score the basketball," Anthony recalled. "[That] made me kind of want to play with him whenever I got a chance.

It's a tantalizing vision: the selfless, pass-happy, point forward from Akron, serving up alley-oops and bullet passes to the powerful, sleek-shooting scoring forward from Baltimore—a partnership made in basketball heaven.

Before they ever reached the NBA, Anthony and James fantasized about the possibilities.

"That was the first conversation: How are we going to play together?" Anthony said. "He was like, 'Man, I want to play with you. How are we going to play together?'"

As teammates, they might have ranked among the best tandems ever. Entering the NBA in the same draft seemingly made it an impossibility. But not entirely.

EARLY IN THE summer of 2006, three budding NBA stars—rivals, friends and members of the same draft class—got on the phone to discuss their futures.

Each was in the third year of his rookie contract and was now eligible for an extension of up to five years.

"Listen," James told his buddies on the conference call, "I think I'm going to do a three-year extension, because in 2010 we can become free agents at the peak, right there in the prime of our career."

A longer deal meant more guaranteed money. A shorter deal held risks. But James wanted to keep his options open. Wade did, too. They opted for three-year, $60 million extensions that would expire in 2010, together.

"And, uh, Melo," James said, smiling and chuckling softly, "Melo took the five-year."

The decision for Anthony seemed simple at the time. The Nuggets were competitive, after all, and the five-year deal would pay $80 million.

"I wanted to stay in Denver," Anthony said. "Like, I believed in Denver so much that I felt like we had an opportunity to do some things out there."

This brings us to the other great "what if" of Anthony's career—indeed, the seminal turning point for everyone in the Brotherhood.

We know how 2010 free agency played out: James and Wade joined forces in Miami and pulled in Chris Bosh—another 2003 draftee who took the short extension—to form a new powerhouse. They made four straight Finals, won two championships and caused convulsions across the league.

James and Anthony met once in the postseason, a series that saw James' Heat dispatch the Knicks in five games. (Issac Baldizon/Getty Images)

(They also smoked the Knicks, 4-1, in the 2012 playoffs, the only time James and Anthony have ever met in the postseason.)

We'll never know how July 2010 would have looked had Anthony taken the hint and taken the short deal. He might have become the third member of the Heatles or linked up with James in New York or Chicago.

Having denied himself that chance, Anthony instead forced a trade to New York the following year, to join forces with Stoudemire.

Looking back, Anthony can only smile ruefully at the missed opportunity, the missed cues. Once James and Bosh landed with Wade on South Beach, "it was like, 'OK, they knew something,'" Anthony said, chuckling.

Knew something?

"Yeah, they plotted that," he said, still chuckling. "They plotted that."

So, why didn't they tell you?

"I guess they was telling me, in their own way: 'Take the three-year deal.'"

The quote is relayed to James, who affirms, "We were."

IT IS RARE for Anthony—talented, accomplished, immensely prideful—to publicly admit regrets, and he only hints at it now, as he considers the road not traveled. But you sense it, in offhand remarks and intonation and in the anecdotal snippets he chooses to share.

"I fell in love with his game."

"How are we going to play together?"

If he had to do it over again, you have to believe Anthony would have chosen the path that led to LeBron. And that, if the opportunity arose, he might still.

Anthony loves New York, loves the spotlight at Madison Square Garden, loves being a Knick. Despite the losing, the frustration, the backlash. But there may come a breaking point.

Anthony has long said how much he enjoys and wants to continue playing in New York, but the Knicks' persistent losing is wearing on him. (Photo: Nathaniel S. Butler/Getty Images)

The Knicks' failures have become Anthony's burden, though they are not solely his responsibility. The mindless zeal of Garden officials to create a rival Big Three was poorly executed, resulting in a lineup—Anthony, Stoudemire, Tyson Chandler—that was haphazard and ultimately doomed.

The Knicks have had one meaningful season in Anthony's tenure, a 54-win campaign in 2012-13 that happened almost by accident and was clearly unsustainable even as it unfurled. They cratered the next season and are now trudging through another rebuild.

In five years as a Knick, Anthony has played with 70 teammates, for four head coaches and four heads of basketball operations. This isn't what he envisioned, though it shouldn't be surprising, either. Chaos, after all, is what the Knicks do.

Where James chose the stability of Miami and Pat Riley, Anthony tied his fate to Jim Dolan, the maladroit Knicks owner.

Where James chose Wade and Bosh, complementary co-stars, Anthony chose a Knicks team that had just rebuilt around Stoudemire, another scoring-minded forward whose game never meshed with Anthony's.

The cruel truth is that Anthony has repeatedly made career choices that put him in this bind:

• Opting for the five-year deal in 2006, instead of free agency in 2010.

• Forcing a trade to the Knicks in February 2011—a move that cost them four starters and multiple draft picks—instead of waiting to sign as a free agent that summer.

• Choosing to stay with the Knicks in 2014, rather than joining contenders in Chicago or Houston.

• And the contract he signed (a near-max $124 million over five years) has, like the deals before it, increased the difficulty of building a supporting cast.

At every turn, Anthony has chosen financial security—the most years, the most money—over flexibility and a chance to compete at a higher level.

Though he visited the Bulls while a free agent in 2014, Carmelo chose to remain with the Knicks rather than joining forces with Derrick Rose. (Photo: Nathaniel S. Butler/Getty Images)

The losing and the criticism have taken an emotional toll, though Anthony insists he is not considering a trade demand or imagining himself in other uniforms or doing anything other than trying to make the Knicks a winner again.

James is enduring his own frustrations in his second tour with Cleveland. But he is still favored to make a sixth straight trip to the Finals, while Anthony is almost certain to miss the playoffs.

Anthony is happy for James. James is concerned for Anthony. But no one is comparing statistics or trophy cases. Friends first, rivals second.

"The only thing that I care about with Melo is when I'm watching the games that he's playing, that he's playing with a smile on his face," James said. "That's it. If Melo got a haircut and a smile on his face, that's when I know he's in a good zone."

James laughed deeply. "He start growing that hair out and that beard out—he ain't feeling too good about himself.

"But when he's playing with that bounce that I've seen since he was 16, and he's playing with that smile that the New York fans see, he's very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very good," James said, his voice rising in pitch. "He's great. He's a great player, man."

All these years later, the mutual admiration remains potent. Whatever their mood, ask James about Anthony or Anthony about James, and you will get a smile, a story, a spirited endorsement.

Decisions have been made, trades forced, contracts signed, fates chosen, taking the teen stars down starkly different paths. The bond endures. The vision of a James-Anthony partnership does, too.

"I really hope that, before our career is over, we can all play together," James said. "At least one, maybe one or two seasons—me, Melo, D-Wade, CP—we can get a year in. I would actually take a pay cut to do that."

Maybe at the end of their careers, James said. Maybe sooner. One more ring chase, this time with everyone on board.

"It would be pretty cool," James said. "I've definitely had thoughts about it."

Before bounding away, he smiles and closes with a coy chirp: "We'll see."

ON THE NIGHT before they became rivals, two basketball prodigies happened upon each other in a hotel lobby, their aspirations boundless, their futures yet to be written.

"You Melo, right?"

"Yeah."

"I'm LeBron. I love your game."

"We just started talking," Anthony said.