Doobie Doo

Veteran

Living in Fear

PROBATION IS MEANT TO KEEP PEOPLE OUT OF JAIL. BUT INTENSE MONITORING LEAVES TENS OF THOUSANDS ACROSS THE STATE AT RISK OF INCARCERATION.

THE PROBATION TRAP

Living in Fear

ALL STORIES

By Samantha Melamed and Dylan Purcell

October 24, 2019

PROBATION IS MEANT TO KEEP PEOPLE OUT OF JAIL. BUT INTENSE MONITORING LEAVES TENS OF THOUSANDS ACROSS THE STATE AT RISK OF INCARCERATION.

THE PROBATION TRAP

Living in Fear

ALL STORIES

By Samantha Melamed and Dylan Purcell

October 24, 2019

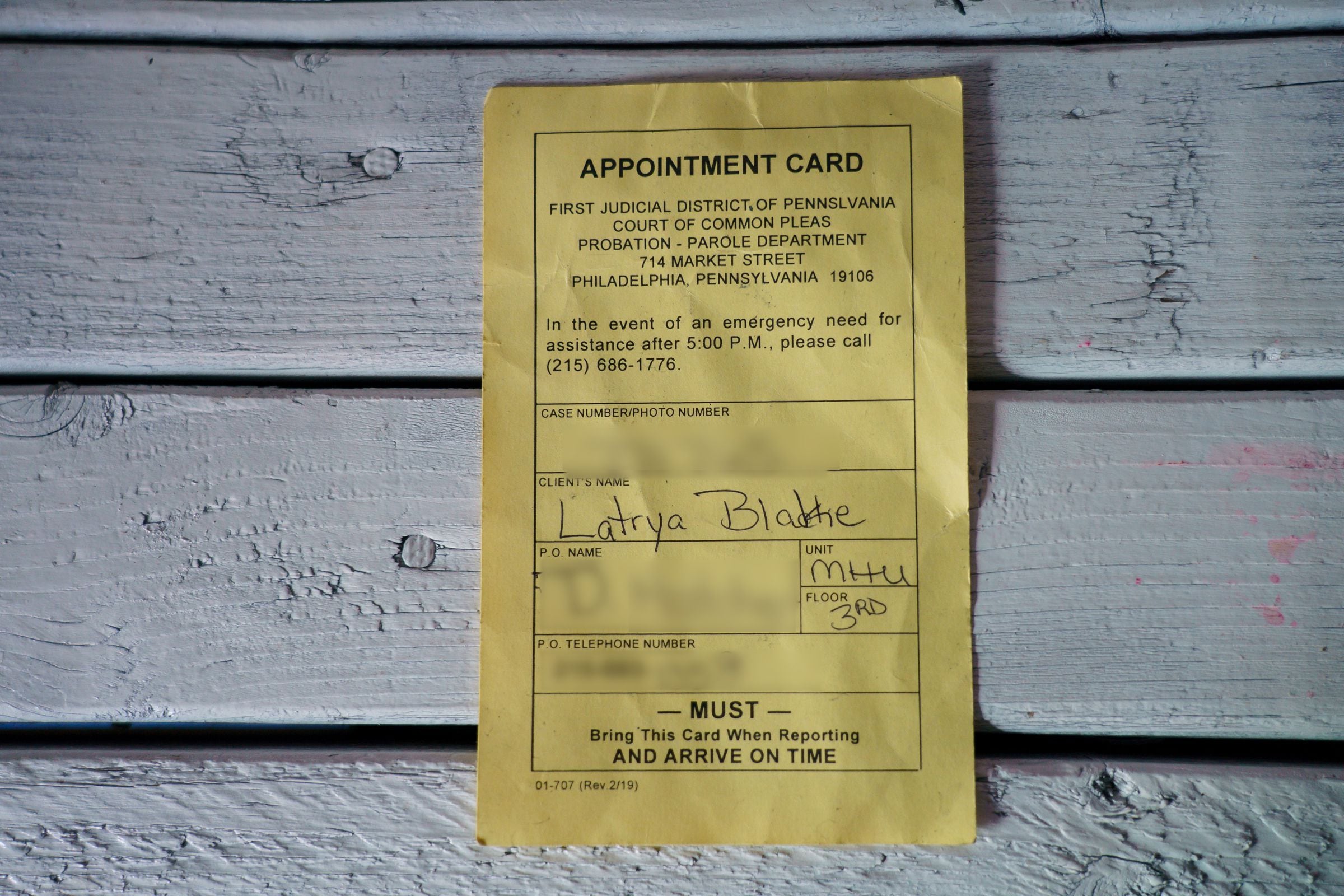

- 290,000 people across Pennsylvania — has developed new anxieties while under supervision, where the tiniest misstep can lead to severe consequences.

On house arrest, he constantly fretted that the electronic monitor would malfunction — a common complaint — and that armed officers would knock down his door and haul him to jail. “It even affected my sleep. I would hear someone at the door, and I would jump up and check [the monitor].”

JESSICA GRIFFIN / Staff Photographer

Khalil Lizzimore, who is now 27, will remain on probation until he's 38 years old. He was convicted of felony gun charges after he bought a gun illegally for his own protection.

These days, Lizzimore, who has a tidy beard and a complicated network of tattoos, looks at everyone with suspicion. “If I take a ride with someone, I’m thinking: ‘Does he have something in his car? Is his license and registration good?’ I feel like I take a risk every day, not even because of something I’m going to do, but because of something life throws at me.”

Lizzimore’s anxiety is well-founded. On an average day, there are 7,443 Pennsylvanians incarcerated as a result of a supervision violation, costing taxpayers $334 million every year.

The case of Meek Mill, who was jailed three times on minor violations while on probation for nearly a decade, has become the prime example of how probation and parole, often proposed as a means to counter over-incarceration, can instead fuel it.

PROBATION AND PAROLE IS THE ONE THING THAT ACTUALLY KEEPS OUR GUYS INSIDE [PRISON] MORE THAN ANYTHING ELSE.

Toorjo Ghose, Center for Carceral Communities at the University of Pennsylvania

From 1980 to 2016 — a period when the crime rate fell by 50% nationwide — the number of people on probation and parole more than tripled. During that time, the jail and prison populations also quadrupled, bringing nearly seven million people nationwide under some form of correctional control.

In Pennsylvania, this net of correctional control has grown unchecked — a result of unusual state laws that set few limits on probation or parole and a courthouse culture in which judges, working without guidelines, impose probation in at least 70% of cases.

That net has ensnared Philadelphia’s African American residents in startling numbers, keeping them on probation at a rate 54% higher than their white counterparts. For young black men like Lizzimore, it means they’ll be subject to monitoring through their 20s and most of their 30s. “It’s a hidden cancer in the system,” said Toorjo Ghose, who runs the Center for Carceral Communities at the University of Pennsylvania. “Probation and parole is the one thing that actually keeps our guys inside [prison] more than anything else.”

In many parts of the country, Lizzimore’s sentence would not even be legal. At least 31 states have capped probation terms at five years.

“You’re telling me, ‘I’m giving you 12 years to mess up,’ ” Lizzimore said. If he does, a judge could find him in violation, revoke probation, and resentence him — up to that 14-year maximum prison sentence.

The growth in supervision has, indeed, led to a remarkable rise in probation violations, flooding court dockets and filling county jails, accounting for at least 40% of prisoners in Philadelphia.

The majority of those violations did not even involve a new crime. Instead, a review of hundreds of cases across Philadelphia and its suburban counties reveals a system that frequently punishes poverty, mental illness, and addiction.

Many who were locked up said they didn’t have car fare to travel to the probation office, or they anticipated losing their jobs if they left early to report to probation.

Those on probation describe a shrinking of their horizons — a life of uncertainty and fear, with trip wires at every turn. “Probation is supposed to help you,” Lizzimore said. “Probation has become a trap.”

JESSICA GRIFFIN / Staff Photographer

Khalil Lizzimore, center and seen from behind, hugs a friend while serving as a volunteer for Frankford Fun Day Bookbag Giveaway in Philadelphia, on Aug. 28, 2019. Community service was court-ordered as part of his probation, though Lizzimore said he was already doing volunteer work.

WHAT’S PROBATION FOR?

“WHEN I STARTED as a public defender,” said Nyssa Taylor, who now works at the ACLU of Pennsylvania, “I thought a probation sentence was a win. I was keeping people out of jail.”

Now, Taylor and many others believe that this was a fundamental misunderstanding of the system — that probation, a supposedly lenient sentence, can ultimately lead to surprisingly harsh punishments. But that misunderstanding has fueled the system’s out-of-control expansion, as probation is imposed for reasons far afield from its stated purpose of rehabilitation.

It raises the question: What’s probation for?

To Erika Pruitt, president of the American Probation and Parole Association, the answer is simple: “You’re working with people on probation so they can live in their communities and not victimize. You’re not only helping an individual change their lives; you’re helping to restore their family and you’re helping to build communities.”

In practice, though, probation is also called on for a number of other purposes. It’s used as a release valve for prisons and jails, as a means to force people to participate in drug and mental health treatment, and as a screw for collecting fines and restitution.

It is, in one respect, the junk drawer of the criminal justice system. Judges use it to accommodate all those low-level cases the system has no other obvious recourse to address. Among a recent sampling: six months’ probation for stealing a package worth $20 off a neighbor’s doorstep; one month for a seven-year-old marijuana charge that, for various reasons, had not previously been resolved; a year for a vehicle inspector who falsified an auto title for a customer who would go on to commit insurance fraud.

WATCH: HOW PROBATION CAN LEAD TO INCARCERATION

Probation is supposed to keep you out of jail. So why are so many in jail for violating probation? In this video we explain in less than three minutes why that happens. (2:55)

“My theory in these low-level offenses is that it’s so the court can be perceived as doing something,” said Michelle Phelps, a University of Minnesota sociologist who studies probation.

Some people who have led lives with little structure, access to treatment, or connection to services say they benefited from their time under probation.

One is Tina Price, 41, whose struggles with substance use led to a 2016 retail-theft conviction and two years of probation in Delaware County. “They’ve given me a lot of chances,” Price said. The court-ordered treatment helped her get sober, she said. She even grew to appreciate the weekly drug tests, a check to keep her from slipping.

But even those who run the system believe probation is overused.

At a legislative policy hearing last year, Helene Placey, executive director of the County Chief Adult Probation & Parole Officers Association of Pennsylvania, said that’s true at both on the high end, with overly long sentences, and on the low end as a response to minor offenses.

“We need to stop using probation as a collection agency,” Placey testified. “For low-level, low-risk offenders we need to utilize sentencing options of ‘guilt without further penalty,’ fines, and restitution, as stand-alone sentences on a more regular basis.”

And, those on probation are less likely to succeed than ever before. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 69% of those completing probation did so successfully in 1990, compared with just half in 2016.

Pennsylvania counties have largely mirrored this national trend of ever-mounting violations. Philadelphia issued 80% more probation warrants in 2017 than it did 15 years earlier, an Inquirer analysis of court data found.

what terrible way to live

what terrible way to live