88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

Bryan Stevenson takes on cases to exonerate people wrongfully convicted. "One of the things that pains me is we have so tragically underestimated the trauma, the hardship we create in this country when we treat people unfairly, when we incarcerate them unfairly, when we condemn them unfairly," he says.

Tracy King/iStockphoto

When Bryan Stevenson was in his 20s, he lived in Atlanta and practiced law at the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee.

One evening, he was parked outside his apartment listening to the radio, when a police SWAT unit approached his car, shined a light inside and pulled a gun.

They yelled, "Move and I'll blow your head off!" according to Stevenson. Stevenson says the officers suspected him of theft and threatened him — because he is black.

The incident fueled Stevenson's drive to challenge racial bias and economic inequities in the U.S. justice system.

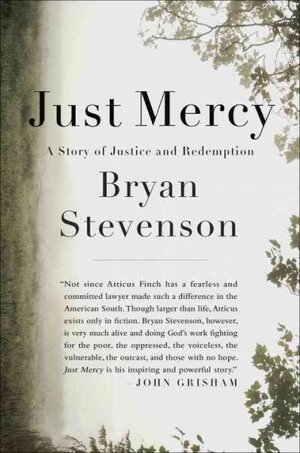

Just Mercy

A Story of Justice and Redemption

by Bryan Stevenson

Hardcover, 336 pages purchase

"[It] just reinforced what I had known all along, which is that we have a criminal justice system that treats you better if you're rich and guilty than if you're poor and innocent," Stevenson tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross. "The other thing that that incident did for me was just remind me that we have this attitude about people that is sometimes racially shaped — and you can't escape that simply because you go to college and get good grades, or even go to law school and get a law degree."

Stevenson is a Harvard Law School graduate and has argued six cases before the Supreme Court. He won a ruling holding that it is unconstitutional to sentence children to life without parole if they are 17 or younger and have not committed murder.

His new memoir, Just Mercy, describes his early days growing up in a poor and racially segregated settlement in Delaware — and how he came to be a lawyer who represents those who have been abandoned. His clients are people on death row — abused and neglected children who were prosecuted as adults and placed in adult prisons where they were beaten and sexually abused, and mentally disabled people whose illnesses helped land them in prison where their special needs were unmet.

In one of his most famous cases, Stevenson helped exonerate a man on death row. Walter McMillian was convicted of killing 18-year-old Ronda Morrison, who was found under a clothing rack at a dry cleaner in Monroeville, Ala., in 1986. Three witnesses testified against McMillian, while six witnesses, who were black, testified that he was at a church fish fry at the time of the crime. McMillian was found guilty and held on death row for six years.

Stevenson decided to take on the case to defend McMillian, but a judge tried to talk him out of it.

"I think everyone knew that the evidence against Mr. McMillian was pretty contrived," Stevenson says. "The police couldn't solve the crime and there was so much pressure on the police and the prosecutor on the system of justice to make an arrest that they just felt like they had to get somebody convicted. ...

"It was a pretty clear situation where everyone just wanted to forget about this man, let him get executed so everybody could move on. [There was] a lot of passion, a lot of anger in the community about [Morrison's] death, and I think there was great resistance to someone coming in and fighting for the condemned person who had been accused and convicted."

But with Stevenson's representation, McMillian was exonerated in 1993. McMillian was eventually freed, but not without scars of being on death row. He died last year.

"This is one of the few cases I've worked on where I got bomb threats and death threats because we were fighting to free this man who was so clearly innocent," Stevenson says. "It reveals this disconnect that I'm so concerned about when I think about our criminal justice system."

Bryan Stevenson is the founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, based in Alabama, and a professor at NYU Law School.

Nina Subin/Courtesy of Random House

Interview Highlights

On how the police got witnesses to testify falsely in the McMillian case

They did coerce the witnesses to testify falsely against him and for some bizarre reason tape-recorded some of these sessions.

So you hear this tape where the witness is saying, "You want me to frame an innocent man for murder? I don't feel right about that."

The police officer is saying, "Well, if you don't do it, we're going to put you on death row, too."

They actually did put the testifying witness on death row for a period of time until he agreed to testify against Mr. McMillian. Other witnesses were given money in exchange for their false testimony.

But it was challenging because even when we presented all of that evidence — and we presented Mr. McMillian's strong alibi, the first couple of judges said, "No, we're not going to grant relief."

It took us six years to get a court to ultimately overturn the conviction. I think it speaks to this resistance we have in this country to confronting our errors, to confronting our mistakes.

On the case taking place where To Kill a Mockingbird is set

One of the really bizarre parts of this whole case for me was this whole episode took place in Monroeville, Ala., where Harper Lee grew up and wrote To Kill a Mockingbird. If you go to Monroeville, you'll see a community that's completely enchanted by that story. ... They have all of this To Kill a Mockingbird memorabilia. The leading citizens enact a play about the book. You can't go anywhere without encountering some aspect of that story made real in that community.

And yet, when we were trying to get the community to do something about an innocent African-American man wrongly convicted, there was this indifference — and, in some quarters, hostility.

On the lasting effects of wrongful convictions and McMillian's dementia

One of the things that pains me is we have so tragically underestimated the trauma, the hardship we create in this country when we treat people unfairly, when we incarcerate them unfairly, when we condemn them unfairly.

You can't threaten to kill someone every day year after year and not harm them, not traumatize them, not break them in ways that [are] really profound. Yet, when innocent people are released, we just act like they should be grateful that they didn't get executed and we don't compensate them many times, we don't help them, we question them, we still have doubts about them.

Read an excerpt of Just Mercy

http://www.npr.org/2014/10/20/356964925/one-lawyers-fight-for-young-blacks-and-just-mercy