The hidden history of slavery in the Islamic world

Summarize

February 22 2025, 12.00am GMT

Memorial sculpture of enslaved people at the Old Slave Market in Stone Town, Zanzibar.

A memorial sculpture to slaves by the Swedish artist Clara Sornas in Zanzibar, Tanzania

ALAMY

Q: What sitcom saved a man from death row after footage from filming confirmed his alibi?

Test your knowledge

Beshir Agha was born in Abyssinia in 1655, seized by slave traders, castrated as a boy and sold for 30 piastres. When he died in 1746 he left a fortune of 30 million piastres, 800 jewel-studded watches and 160 horses. When he was a slave to the Ottoman governor of Egypt, he received an education. He was clearly gifted; he soon found a berth at the Topkapi Palace, the main residence of the Ottoman sultan. There he proved an adept functionary, particularly good at organising lavish entertainments, and a skilful palace politician, rising through the ranks to serve as chief harem eunuch to two sultans.

Beshir is one of the many fascinating characters in Captives and Companions, Justin Marozzi’s history of slavery in the Islamic world. Marozzi starts his account in the 7th century, during the life of Muhammad. Marozzi quotes one of the most famous Quranic pronouncements on slavery, one that treats inequality between master and slave as a fact of life: “Allah has favoured some of you over others in provision.” Allah had evidently favoured the Prophet Muhammad, whose tastes were ecumenical — his 70 slaves included Copts, Syrians, Persians and Ethiopians.

Book cover: Captives and Companions, A History of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Islamic World, by Justin Marozzi. Illustration of a historical battle scene.

The sexual exploitation of female slaves by their male owners is permissible too, counsels the Quran. This furnished the Ottoman sultans with an alibi for their harem of enslaved concubines — and in our time armed Islamic State with a sanction for the rape and enslavement of Yazidi women in northern Iraq. As Marozzi rightly argues in this history of slavery in the Islamic world, it is disingenuous to deny the Islamic State its Islamic character, as Barack Obama once attempted. These are not secular fanatics but Muslim fundamentalists. For centuries Quranic justifications were invoked to defend slavery as a cultural tradition — as if it were no more troubling than morris dancing.

Small wonder, then, that Muslim nations were among the last to abolish it — Saudi Arabia in 1962, Oman in 1970, Mauritania in 1981. But the practice persists. In Saudi Arabia, according to the Global Slavery Index, there are 740,000 people living in modern slavery. Marozzi opens his book in the Kayes region of western Mali, where hereditary slavery persists, as does the right of masters to rape the wives and daughters of their slaves.

Despite its long history and continued presence, however, slavery in the Islamic world remains woefully underresearched. Western parochialism bears some blame; James Walvin’s A Short History of Slavery, for example, devotes 201 of its 235 pages to the Atlantic trade. But so does western timidity. The historian Bernard Lewis once lamented that, thanks to contemporary sensibilities, it had become “professionally hazardous” for bright young things to probe slavery in Muslim societies.

• Read more of the latest religion news, views and analysis.

Thankfully Marozzi is unencumbered by such PC pretensions. He is careful with words, preferring “the slave trade in the Islamic world” to “Muslim slavery” — as we do not, after all, call the Atlantic trade “Christian slavery”. Likewise, he never deserts perspective. While discussing the million or so European Christian captives taken by Barbary corsairs, he reminds us that Christendom enslaved twice as many Muslims in the early modern period. If the Arabs enslaved 17 million souls between AD650 and 1905, Marozzi says that we would do well to remember that nearly as many — perhaps 14 million — Africans were claimed by the Atlantic trade in a much shorter period.

18th-century illustration of concubines bathing in the Topkapi Palace harem.

Concubines in a Bath, 18th-century miniature by Fazil Enderuni

ALAMY

Captives and Companions, then, is an unsentimental unveiling of a subject that has long been enshrouded in scholarly purdah. To be sure, Marozzi breaks no new ground in these pages, drawing heavily on recent work by North African, Turkish and a handful of western scholars. Yet the result is an elegant and ambitious synthesis, serving up a scintillating compendium of potted lives.

We meet Bilal ibn Rabah, the Ethiopian slave who in AD610 “had his head turned” by the self-styled Prophet Muhammad, rejecting the old gods to become one of his first followers. For this Bilal was tortured by his master, Umayya ibn Khalaf — who met his end at the Battle of Badr in AD624, cut down by his former slave after the prophet’s fledgling army routed the Quraysh tribe. Muhammad then appointed Bilal the voice of Islam; as the first muezzin (the caller to prayer), his voice — a resonant baritone — was the one the earliest Muslims heard five times daily, beckoning them to prayer.

• The 21 best history books of the past year to read next

That was Islam in its radical infancy. Later Arabs, Marozzi shows, shed Muhammad’s colour-blindness and took up trafficking darker-skinned Africans. Racism ran deep. Even an intelligent fellow like the 10th-century historian Masudi could be dismayingly provincial and downright racist in his descriptions of black Africans. The Zanj, as they were called, had ten qualities, he wrote: “Kinky hair, thin eyebrows, broad noses, thick lips, sharp teeth, malodorous skin, dark pupils, clefty hands and feet, elongated penises, and excessive merriment.” Chafing under the Arab yoke, they struck back in AD869, launching what may have been history’s largest slave revolt. For 14 years they flattened cities, torching mosques and enslaving their former slaveholders. Something like a million lives were lost before the Zanj Rebellion was quelled.

If male slaves could pose a physical threat, female slaves were another kind of risk. The Nestorian physician Ibn Butlan, writing in the 11th century, offered cautionary counsel: resist lustful impulse purchases “for the tumescent has no judgment, since he decides at first glance, and there is magic in the first glance”. The concubine Arib beguiled no fewer than eight caliphs over seven decades. Al-Amin, clearly a paedophile, adored her when she was still in her early teens, and Mutamid, surely a gerontophile, loved her in her seventies. Even into her nineties she was propositioned, although she demurred: “Ah, my sons, the lust is present, but the limbs are helpless.”

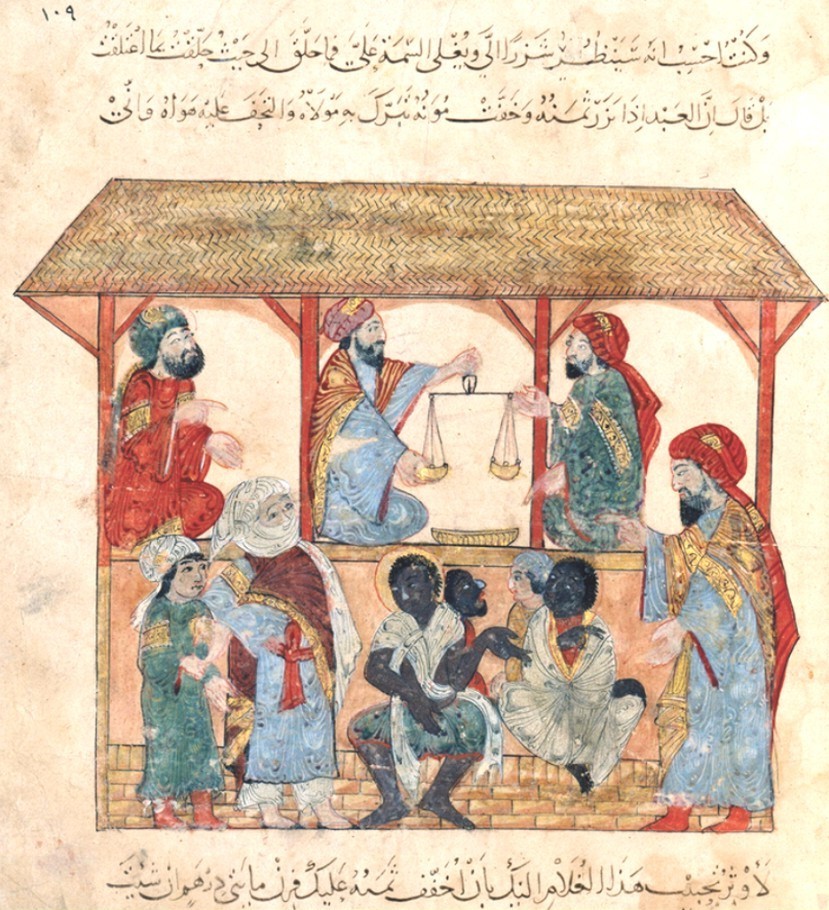

Illustration of a 13th-century slave market in Zabid, Yemen.

A 13th-century slave market in Zabid, Yemen

Less threatening were enslaved eunuchs. Although the Quran forbade castration, the enterprising Abbasids found a workaround since their ever-expanding harems needed a steady supply of unthreatening men. Infidels in sub-Saharan Africa did the dirty work of sourcing and exporting eunuchs. It was a gruesome business. Even as late as in the 19th century, nine in ten boys put under the knife died. Western visitors were horrified by the presence of eunuchs in the holy places, although Marozzi might have noted that Christianity, too, had its eunuchs — the Sistine Chapel’s last castrato wasn’t retired until 1903.

Gliding through the ages, dropping a metaphor here and a maxim there, Marozzi’s prose recalls an older tradition of history writing — the effortless fluidity of a John Julius Norwich or Jan Morris. Reading him, one thinks of Tintoretto: vast canvases, mannered style, high drama, narrative drive. But it has its drawbacks. Marozzi, whose previous books include The Arab Conquests and Islamic Empires, delights in the zany and lurid. He loves his lobbed heads and unruly libidos, his swivel-eyed slavers and concupiscent concubines.

Consider the tale of Thomas Pellow, “an eleven-year-old Cornish lad” who, in 1715, ignored his parents’ warnings and set sail from Falmouth in search of adventure. “If only he had listened to them,” Marozzi sighs. Snatched by Moroccan corsairs off Cape Finisterre, Pellow landed in Meknes, where beatings and bastinadings — feet flayed while strung upside down — quickly dulled his taste for colourful exploits. To save his skin he “turned Turk”, although he later insisted it was all for show: “I always abominated them and their accursed principle of Mahometism.”

• Read more book reviews and interviews — and see what’s top of the Sunday Times Bestsellers List

As slaves go, he did well. He climbed the ranks, led a 30,000-man slave raid into Guinea and did as he was told, “stripping the poor negroes of all they had, killing many of them, and bringing off their children into the bargain”. Then came the compulsory marriage in order to sire more slaves for his master: eight African women were paraded before him, but Pellow, bigoted fellow that he was, turned them down, “not at all liking their colour”. He demanded a wife “of my colour” and was duly granted one, although by now he was hardly a pasty Cornishman. When he escaped he was briefly mistaken for a “Moor”. Back in London, he felt alienated from his homeland — until he ended up at dinner at the Moroccan ambassador’s, who offered him “my favourite dish”: a big bowl of couscous.

Captives and Companions: A History of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Islamic World by Justin Marozzi (Allen Lane £35 pp560). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members

asianreviewofbooks.com

asianreviewofbooks.com