Secret changes to major U.S. health datasets raise alarms

A new Lancet study reveals that over 100 U.S. government health datasets were quietly altered in early 2025, raising alarms among researchers about transparency, political influence, and the reliability of data used in public health and social science research.

www.psypost.org

Secret changes to major U.S. health datasets raise alarms

by Eric W. Dolan

July 15, 2025

in Exclusive

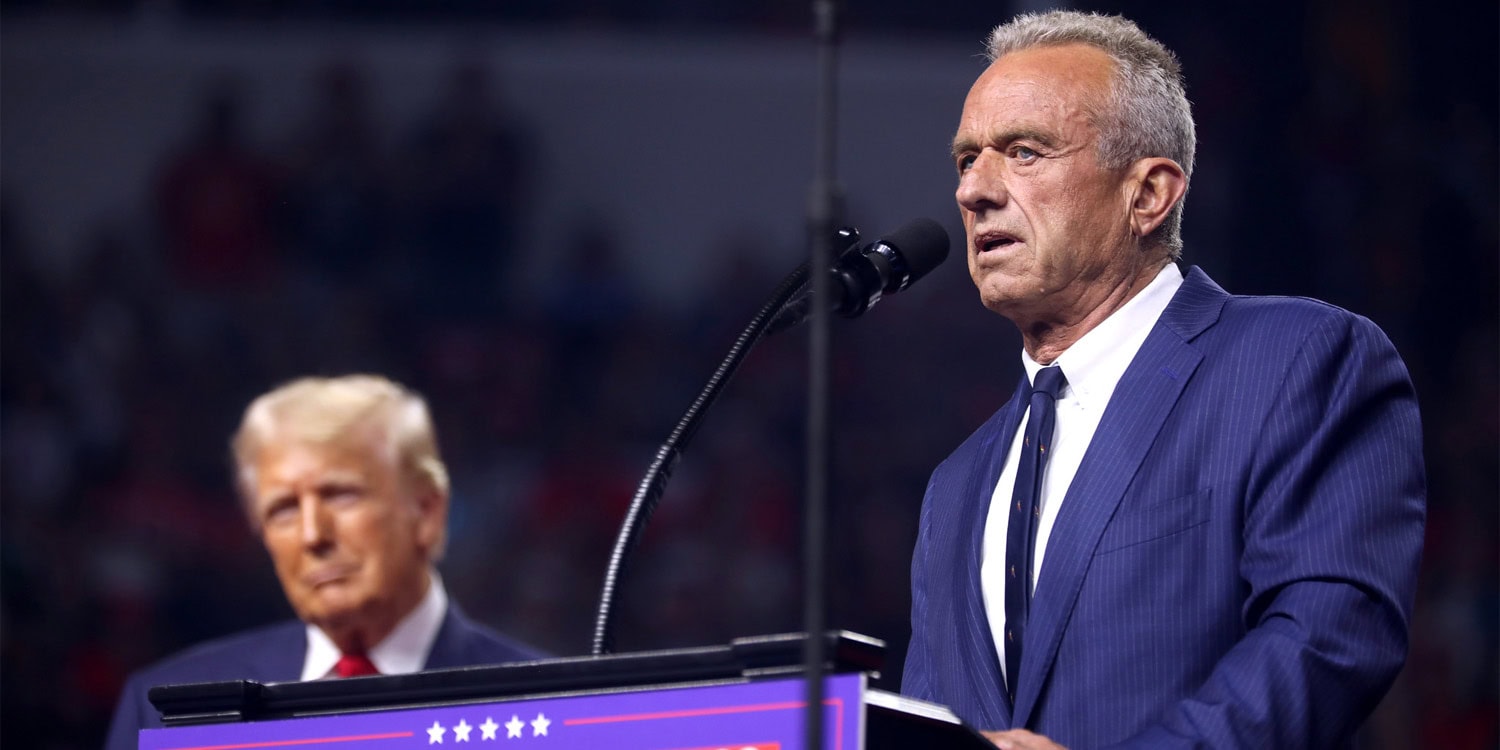

[Photo by Gage Skidmore]

A new study in the medical journal The Lancet reports that more than 100 United States government health datasets were altered this spring without any public notice. The investigation shows that nearly half of the files examined underwent wording changes while leaving the official change logs blank. The authors warn that hidden edits of this kind can ripple through public health research and erode confidence in federal data.

To reach these findings, the researchers started by downloading the online catalogues—known as harvest sources—that federal agencies maintain under the 2019 Open Government Data Act. They gathered every entry from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Department of Veterans Affairs that showed a modification date between January 20 and March 25, 2025.

After removing duplicates and files that are refreshed at least monthly, the team was left with 232 datasets. For each one, they located an archived copy that pre‑dated the study window, most often through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

They then used the comparison feature in a word‑processing program to highlight every textual difference between the older and newer versions. Only wording was assessed; numeric tables were not rechecked. Finally, the investigators opened the public change log that sits at the bottom of each dataset’s web page to see whether the alteration had been declared.

One example captures how the edits appeared in practice. A file from the Department of Veterans Affairs that tracks the number of veterans using healthcare services in the 2021 fiscal year had sat untouched for more than two years. On March 5, 2025, the column heading “Gender” was replaced with “Sex.” The same swap was made in the dataset’s title and in the short description at the top of the page. The modification date on the site updated to reflect the change, yet the built‑in change log still reads, “No changes have been archived yet.”

Across the full sample, the pattern was strikingly consistent. One hundred fourteen of the 232 datasets—49 percent—contained what the authors judged to be potentially substantive wording changes. Of these, 106 switched the term “gender” to “sex.” Four files replaced the phrase “social determinants of health” with “non‑medical factors,” one exchanged “socio‑economic status” for “socio‑economic characteristics,” and a single clinical trial listing rewrote its title so that “gender diverse” became “include men and women.”

In 89 cases, the revision affected text that defines the data itself, such as column names or category labels. The remaining 25 changes occurred in narrative descriptions or tags that sit above the data table. Only 25 of the 114 altered files—less than one in seven—acknowledged the revision in their official logs.

The timing followed a marked acceleration: four edits occurred in the final days of January, 30 during February, and 82 during the first three and a half weeks of March—suggesting an intensified push as spring approached.

These government datasets form the backbone of countless psychology, sociology, and public health projects. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, for instance, supplies yearly survey information on smoking, exercise, diet, and chronic illness across every state. It is routinely mined to study links between health behavior and mental well‑being.

Heart disease and stroke mortality files from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention help social scientists examine how stress, neighborhood environment, or discrimination align with geographic patterns in illness and death.

Nutrition and physical activity surveys inform work on childhood obesity and its ties to screen time or family structure. Researchers who focus on veteran mental health rely on Department of Veterans Affairs summaries to track service‑connected disability, access to therapy, and suicide risk among former service members.

When variable labels shift from “gender” to “sex” in these resources, studies that compare answers given under the old wording with figures retrieved after the change are no longer aligning like‑with‑like. Even a single undocumented edit can scramble replication attempts, invalidate earlier statistical models, or make it impossible to detect real trends in the underlying population.

The implications stretch beyond statistical concerns. Survey designers distinguish between gender, a social identity, and sex, a biological classification, because the two terms capture related but not identical information. Many transgender and non‑binary respondents, for example, select a gender option that differs from the sex recorded on their birth certificate.

If the government retroactively re‑labels a column without clarifying whether the underlying question also changed, analysts cannot tell whether a fluctuation in the male‑to‑female ratio reflects genuine demographic shifts, a wording tweak, or recoding behind the scenes. Public health officials may then allocate resources on a faulty premise, and medical guidelines that depend on demographic baselines can drift off target.

The authors of the study point to a possible political origin for the edits. They note that the White House issued a directive in early February instructing agencies to purge material seen as advancing “gender ideology”—language echoed by several state administrations.

No federal office has publicly confirmed that the dataset edits were carried out in response, yet the timing and the tight focus on the term “gender” hint at coordinated action. If the goal was to bring terminology across agencies into alignment, the transparency required by the Open Government Data Act appears to have been set aside.

The investigation is not without limits. Because many archives extend back only a few years, the researchers could not examine earlier periods for similar actions. They judged whether a change was routine or substantive by hand, an approach that introduces subjectivity. They also left numerical content untouched; it remains unknown whether any figures were edited alongside the wording.

In response to the findings, the authors suggest a series of steps that scholars and institutions can take to protect the reliability of public data. Independent groups already mirror many federal datasets on private servers, and individual investigators can save local copies of files they intend to analyze. Routine spot checks against archived versions can help reveal unexpected alterations.

International repositories such as Europe PubMed Central offer alternative hosting for biomedical resources, lowering dependence on any single government. Most important, the researchers argue, is a cultural commitment to full version tracking inside federal agencies—so that every member of the public can see exactly what changed, when it changed, and why.

The study, “Data manipulation within the US Federal Government,” was authored by Janet Freilich and Aaron S. Kesselheim.