IllmaticDelta

Veteran

I don't think most people are aware of the huge ADOS history in Europe from the more recent times, all the way back to more than 200 years ago. So this thread will bring to light some of that history. To start off

.

.

.

JAMES c00nEY (BACK, LEFT) SEEN WITH COLLEAGUES IN ALEX DAY’S BEACH ENTERTAINERS OF MORECAMBE, LANCASHIRE IN 1910 IS SAID TO HAVE SETTLED IN THAT TOWN AROUND 1902 BUT HE MARRIED A LOCAL GIRL IN 1898, HAVING WORKED AS A CIRCUS PERFORMER AND WITH THE BOHEE BROTHERS, AND SERVED IN THE ARGENTINE NAVY. HE DIED IN MORECAMBE IN 1932.

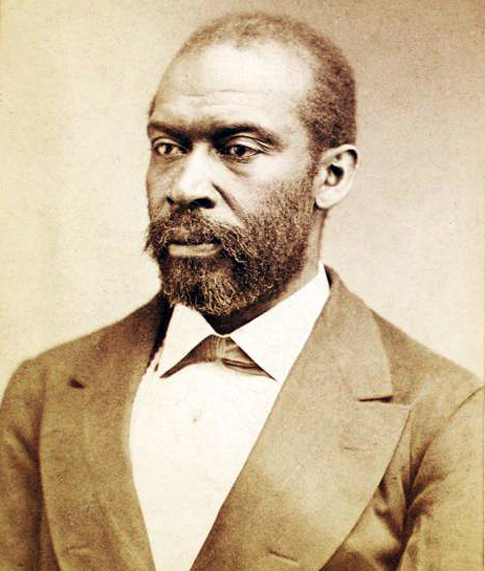

CALVIN HARRIS RICHARDSON AND THOMAS LEWIS JOHNSON STUDIED IN STOCKWELL,

LONDON IN THE LATE 1870S. WITH THEIR WIVES, SISTERS ISSADORAH AND HENRIETTA,

THEY WENT TO CAMEROON IN 1878 AS BAPTIST MISSIONARIES. HENRIETTA JOHNSON DIED

THERE AND HER HUSBAND RETURNED TO ENGLAND IN JANUARY 1880, VERY ILL. AFTER

MISSION WORK IN THE U.S.A., JOHNSON SETTLED IN LONDON THEN BOURNEMOUTH

WHERE HE DIED IN 1921. HIS TWENTY-EIGHT YEARS A SLAVE WAS PUBLISHED IN

BOURNEMOUTH IN 1909 – A MUCH SMALLER EDITION HAD BEEN PUBLISHED IN LONDON

IN 1882. THE RICHARDSONS REMAINED IN CAMEROON THEN RETIRED TO THE U.S.A.

Incredible images show Samuel Ringgold War who escaped to Britain in 1853 and had his book Autobiography of a Fugitive Slave published in 1855, Marta Ricks who was born a slave in Tennessee before arriving in Britain via Liberia and even met Queen Victoria, and Thomas Lewis Johnston who went to Cameroon as a Baptist missionary before settling in England.

more...

MARTHA RICKS. BORN A SLAVE IN

TENNESSEE SHE WAS SENT TO LIBERIA IN

1830. IN 1892 SHE SAILED FROM AFRICA

TO LIVERPOOL AND FULFILLED A LONG

AMBITION TO MEET QUEEN VICTORIA. SHE

PRESENTED THE MONARCH WITH A QUILT

SHOWING LIBERIAN COFFEE PLANTS. BRITISH

NEWSPAPERS REPORTED HER VENTURE

WITH SURPRISE AND RESPECT. COPYRIGHT

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON,

Other striking shots show world bantamweight boxing champion George Dixon who fought in London in 1890, Peter Thomas Stanford who became the minister of Hope Street Baptist church in Birmingham, UK in 1889 and Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield who sang for Queen Victoria in Buckingham Palace.

Their remarkable stories are told in Jeffrey Green’s new book, Black Americans in Victorian Britain, published by Pen and Sword.

GEORGE DIXON WAS THE WORLD

BANTAMWEIGHT BOXING CHAMPION IN

1888 AND FOUGHT IN LONDON IN 1890.

HE WAS A FEATHERWEIGHT CHAMPION

FROM 1891. BORN IN HALIFAX, NOVA

SCOTIA, IN 1870 HE LIVED IN BOSTON,

MASSACHUSETTS.

“British attitudes were affected by the testimony of these black witnesses who informed the British and Irish about life in the United States,” he writes in the book’s introduction.

“Individuals made their homes in Britain and married British people to an extent which might have surprised historian Benjamin Quarles who commented in 1969: ‘they posed no threat to the laboring man or to the purity of the national blood stream. Hence they received that heartiest of welcomes that comes from a love of virtue combined with an absence of apprehension’.

PAUL DUNBAR’S POEMS WERE WELL

RECEIVED IN AMERICA AND IN 1897 HE

VISITED ENGLAND FOR SOME MONTHS.

THE TIMES REVIEWED HIS COOPERATION

WITH AFRO-BRITISH COMPOSER SAMUEL

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR, NOTING HE POSSESSED

AN ‘UNDENIABLE POETICAL GIFT’.

“Some refugees did not return after slavery was abolished and the Confederacy defeated.

PETER THOMAS STANFORD FROM VIRGINIA

MIGRATED TO CANADA AND IN 1883 TO

ENGLAND, WHERE HE BECAME THE MINISTER

OF THE HOPE STREET BAPTIST CHURCH IN

BIRMINGHAM IN 1889. HE LEFT FOR THE

U.S.A. IN 1895 AND PUBLISHED THE

TRAGEDY OF THE NEGRO IN AMERICA

IN 1898.

“These and other experiences of African Americans in nineteenth-century Britain reveal overlooked elements in the history of the American people and aspects of the nature of Victorian Britain. Uncovered fragments are part of a mosaic, sometimes with only one piece discovered.”

MOSES ROPER TOURED BRITAIN IN THE LATE 1830S, MARRIED A WELSH WOMAN, AND

THEY MIGRATED TO CANADA. ROPER REVISITED BRITAIN, AS DID HIS WIFE AND DAUGHTERS.

Green’s book aims to name those Americans who immigrated to Britain in the hope that they will be researched in more detail, if he has been unable to find much out.

It also deals with the legacy those immigrants left and the effect it had on America and those who still lived there.

WILLIAM PETER POWELL BORN IN

1834 LEFT NEW YORK WITH HIS

PARENTS AND SIBLINGS IN 1850. HE

STUDIED IN DUBLIN AND MANCHESTER

AND QUALIFIED AS A DOCTOR IN 1858.

HE WORKED IN TWO LIVERPOOL

HOSPITALS AND WHEN THE U.S. CIVIL

WAR BROKE OUT, THE ENTIRE FAMILY

RETURNED TO NEW YORK WHERE

DR POWELL SERVED IN A WASHINGTON

ARMY HOSPITAL. HE DIED IN

LIVERPOOL IN 1916. COURTESY

NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS

ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON DC

FROM RECORDS OF THE DEPARTMENT

OF VETERANS AFFAIRS, RG 15.

THANKS TO JILL L. NEWMARK OF THE

HISTORY OF MEDICINE DIVISION AT

THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

IN BETHESDA, MARYLAND.

“Having crossed the Atlantic towards the rising sun, they had rejected the United States of America,” added Green.

“A number went further east by migrating to Australia and New Zealand suggesting their ambitions had not been satisfied by life in Britain. Thousands of British people migrated to the Antipodes, so we cannot be sure what had encouraged that secondary black migration which like the African American presence in Victorian Britain, is under-researched.

ELIZABETH TAYLOR GREENFIELD

WAS RAISED IN PHILADELPHIA.

SHE WAS BLESSED WITH A SUPERB

SINGING VOICE, WHICH LED HER

TO EUROPE AFTER A NEW YORK

CITY CONCERT IN 1853. IN 1854

SHE SANG FOR QUEEN VICTORIA AT

BUCKINGHAM PALACE.

“The often superficial nature of newspaper reports and inconsistencies in official documents with the spelling of names is one difficulty but the almost total absence of ‘race’ as a concept is a major problem.

“No British birth, marriage or death registrations indicate ‘race’ or ‘color’ as American documents did. Schools, colleges, churches, chapels, graveyards, and street directories do not distinguish between the people they listed. For migrant African Americans, whose entire lives had been defined by the colour of their skin, this official blindness and its apparent recognition by the majority of Britons was so different to their natal land.

“African Americans who had lived in Victorian Britain had an impact on kinfolk in the United States. They influenced the British.”

JESSE EWING GLASGOW FROM

PENNSYLVANIA STUDIED MEDICINE

AT EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY WHERE HE WROTE THE HARPERS FERRY

INSURRECTION IN 1859. HE DIED

IN DECEMBER 1860, A FEW WEEKS

BEFORE GRADUATION.

The Incredible Experiences of Former Slaves Who Fled To Britain During The 19th Century Have Been Unveiled In This New Book | Media Drum World

.

.

.

JAMES c00nEY (BACK, LEFT) SEEN WITH COLLEAGUES IN ALEX DAY’S BEACH ENTERTAINERS OF MORECAMBE, LANCASHIRE IN 1910 IS SAID TO HAVE SETTLED IN THAT TOWN AROUND 1902 BUT HE MARRIED A LOCAL GIRL IN 1898, HAVING WORKED AS A CIRCUS PERFORMER AND WITH THE BOHEE BROTHERS, AND SERVED IN THE ARGENTINE NAVY. HE DIED IN MORECAMBE IN 1932.

CALVIN HARRIS RICHARDSON AND THOMAS LEWIS JOHNSON STUDIED IN STOCKWELL,

LONDON IN THE LATE 1870S. WITH THEIR WIVES, SISTERS ISSADORAH AND HENRIETTA,

THEY WENT TO CAMEROON IN 1878 AS BAPTIST MISSIONARIES. HENRIETTA JOHNSON DIED

THERE AND HER HUSBAND RETURNED TO ENGLAND IN JANUARY 1880, VERY ILL. AFTER

MISSION WORK IN THE U.S.A., JOHNSON SETTLED IN LONDON THEN BOURNEMOUTH

WHERE HE DIED IN 1921. HIS TWENTY-EIGHT YEARS A SLAVE WAS PUBLISHED IN

BOURNEMOUTH IN 1909 – A MUCH SMALLER EDITION HAD BEEN PUBLISHED IN LONDON

IN 1882. THE RICHARDSONS REMAINED IN CAMEROON THEN RETIRED TO THE U.S.A.

Incredible images show Samuel Ringgold War who escaped to Britain in 1853 and had his book Autobiography of a Fugitive Slave published in 1855, Marta Ricks who was born a slave in Tennessee before arriving in Britain via Liberia and even met Queen Victoria, and Thomas Lewis Johnston who went to Cameroon as a Baptist missionary before settling in England.

more...

MARTHA RICKS. BORN A SLAVE IN

TENNESSEE SHE WAS SENT TO LIBERIA IN

1830. IN 1892 SHE SAILED FROM AFRICA

TO LIVERPOOL AND FULFILLED A LONG

AMBITION TO MEET QUEEN VICTORIA. SHE

PRESENTED THE MONARCH WITH A QUILT

SHOWING LIBERIAN COFFEE PLANTS. BRITISH

NEWSPAPERS REPORTED HER VENTURE

WITH SURPRISE AND RESPECT. COPYRIGHT

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON,

Other striking shots show world bantamweight boxing champion George Dixon who fought in London in 1890, Peter Thomas Stanford who became the minister of Hope Street Baptist church in Birmingham, UK in 1889 and Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield who sang for Queen Victoria in Buckingham Palace.

Their remarkable stories are told in Jeffrey Green’s new book, Black Americans in Victorian Britain, published by Pen and Sword.

GEORGE DIXON WAS THE WORLD

BANTAMWEIGHT BOXING CHAMPION IN

1888 AND FOUGHT IN LONDON IN 1890.

HE WAS A FEATHERWEIGHT CHAMPION

FROM 1891. BORN IN HALIFAX, NOVA

SCOTIA, IN 1870 HE LIVED IN BOSTON,

MASSACHUSETTS.

“British attitudes were affected by the testimony of these black witnesses who informed the British and Irish about life in the United States,” he writes in the book’s introduction.

“Individuals made their homes in Britain and married British people to an extent which might have surprised historian Benjamin Quarles who commented in 1969: ‘they posed no threat to the laboring man or to the purity of the national blood stream. Hence they received that heartiest of welcomes that comes from a love of virtue combined with an absence of apprehension’.

PAUL DUNBAR’S POEMS WERE WELL

RECEIVED IN AMERICA AND IN 1897 HE

VISITED ENGLAND FOR SOME MONTHS.

THE TIMES REVIEWED HIS COOPERATION

WITH AFRO-BRITISH COMPOSER SAMUEL

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR, NOTING HE POSSESSED

AN ‘UNDENIABLE POETICAL GIFT’.

“Some refugees did not return after slavery was abolished and the Confederacy defeated.

PETER THOMAS STANFORD FROM VIRGINIA

MIGRATED TO CANADA AND IN 1883 TO

ENGLAND, WHERE HE BECAME THE MINISTER

OF THE HOPE STREET BAPTIST CHURCH IN

BIRMINGHAM IN 1889. HE LEFT FOR THE

U.S.A. IN 1895 AND PUBLISHED THE

TRAGEDY OF THE NEGRO IN AMERICA

IN 1898.

“These and other experiences of African Americans in nineteenth-century Britain reveal overlooked elements in the history of the American people and aspects of the nature of Victorian Britain. Uncovered fragments are part of a mosaic, sometimes with only one piece discovered.”

MOSES ROPER TOURED BRITAIN IN THE LATE 1830S, MARRIED A WELSH WOMAN, AND

THEY MIGRATED TO CANADA. ROPER REVISITED BRITAIN, AS DID HIS WIFE AND DAUGHTERS.

Green’s book aims to name those Americans who immigrated to Britain in the hope that they will be researched in more detail, if he has been unable to find much out.

It also deals with the legacy those immigrants left and the effect it had on America and those who still lived there.

WILLIAM PETER POWELL BORN IN

1834 LEFT NEW YORK WITH HIS

PARENTS AND SIBLINGS IN 1850. HE

STUDIED IN DUBLIN AND MANCHESTER

AND QUALIFIED AS A DOCTOR IN 1858.

HE WORKED IN TWO LIVERPOOL

HOSPITALS AND WHEN THE U.S. CIVIL

WAR BROKE OUT, THE ENTIRE FAMILY

RETURNED TO NEW YORK WHERE

DR POWELL SERVED IN A WASHINGTON

ARMY HOSPITAL. HE DIED IN

LIVERPOOL IN 1916. COURTESY

NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS

ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON DC

FROM RECORDS OF THE DEPARTMENT

OF VETERANS AFFAIRS, RG 15.

THANKS TO JILL L. NEWMARK OF THE

HISTORY OF MEDICINE DIVISION AT

THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

IN BETHESDA, MARYLAND.

“Having crossed the Atlantic towards the rising sun, they had rejected the United States of America,” added Green.

“A number went further east by migrating to Australia and New Zealand suggesting their ambitions had not been satisfied by life in Britain. Thousands of British people migrated to the Antipodes, so we cannot be sure what had encouraged that secondary black migration which like the African American presence in Victorian Britain, is under-researched.

ELIZABETH TAYLOR GREENFIELD

WAS RAISED IN PHILADELPHIA.

SHE WAS BLESSED WITH A SUPERB

SINGING VOICE, WHICH LED HER

TO EUROPE AFTER A NEW YORK

CITY CONCERT IN 1853. IN 1854

SHE SANG FOR QUEEN VICTORIA AT

BUCKINGHAM PALACE.

“The often superficial nature of newspaper reports and inconsistencies in official documents with the spelling of names is one difficulty but the almost total absence of ‘race’ as a concept is a major problem.

“No British birth, marriage or death registrations indicate ‘race’ or ‘color’ as American documents did. Schools, colleges, churches, chapels, graveyards, and street directories do not distinguish between the people they listed. For migrant African Americans, whose entire lives had been defined by the colour of their skin, this official blindness and its apparent recognition by the majority of Britons was so different to their natal land.

“African Americans who had lived in Victorian Britain had an impact on kinfolk in the United States. They influenced the British.”

JESSE EWING GLASGOW FROM

PENNSYLVANIA STUDIED MEDICINE

AT EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY WHERE HE WROTE THE HARPERS FERRY

INSURRECTION IN 1859. HE DIED

IN DECEMBER 1860, A FEW WEEKS

BEFORE GRADUATION.

The Incredible Experiences of Former Slaves Who Fled To Britain During The 19th Century Have Been Unveiled In This New Book | Media Drum World

Last edited: