ogc163

Superstar

Noah Smith 18-23 minutes 10/26/2022

This is a big-think, “sweeping overview” sort of post. I find myself writing more of these recently, not because there aren’t little interesting news items or econ papers or debates to focus on, but because big things are happening very fast in the world right now, and I want to try and keep track of them.

After the end of the Cold War, the United States forged a new world. The driving, animating idea behind this new world was the belief that global trade integration would restrain international conflict. At first this rested on a Fukuyama-type “end of history” theory that political and economic liberalization would follow globalization, but as it became clear that various bureaucratic one-party oligarchies and petrostates (most notably China and Russia) were resistant to the end of history, the hopes for trade became more modest — at least countries that depended on each other economically would not fall into active conflict.

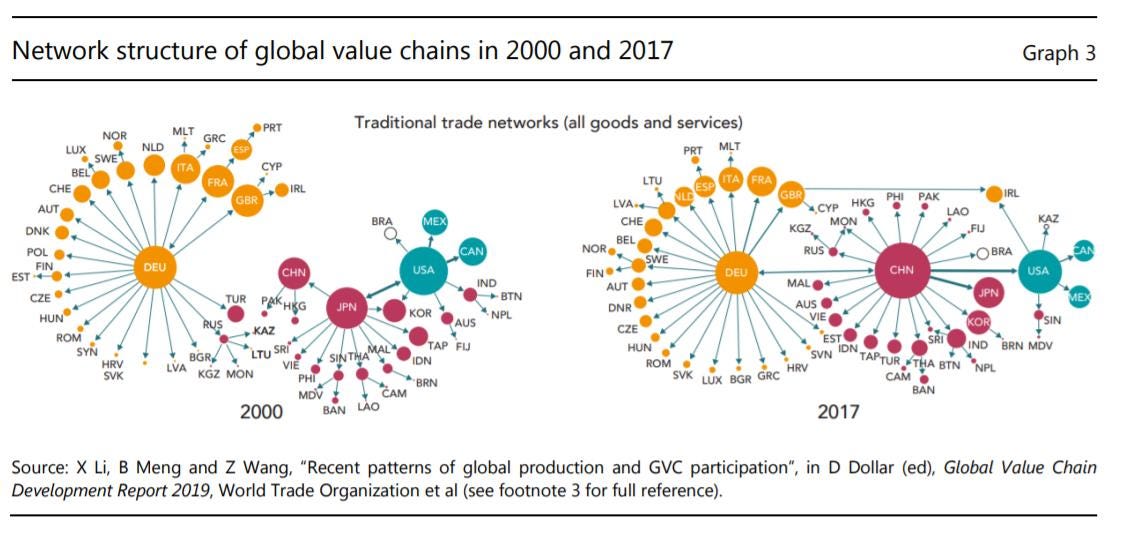

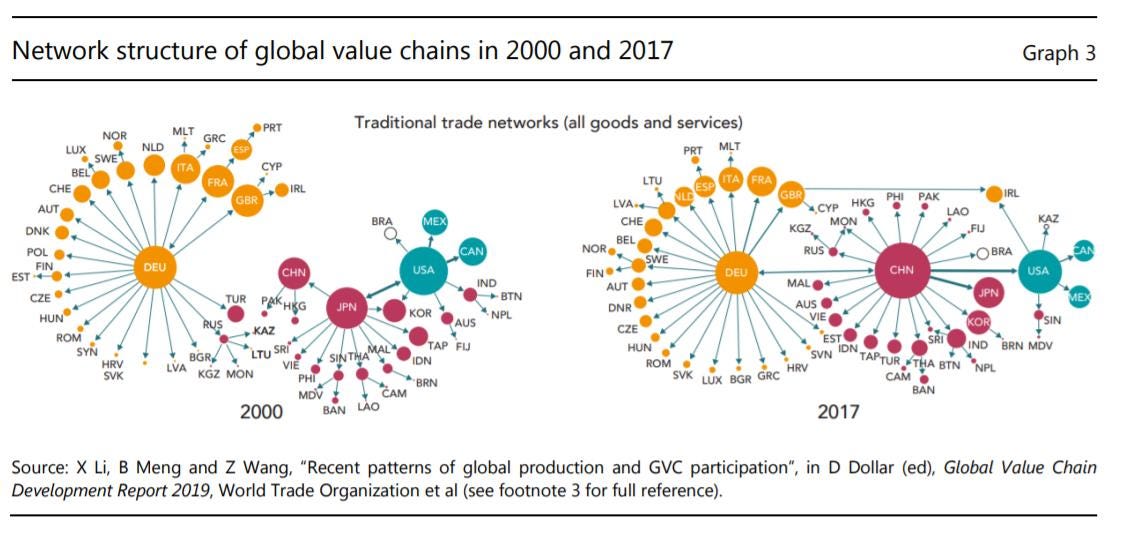

We didn’t just pay lip service to this theory; we bet the entire world on it. The U.S. and Europe championed the admission of China into the World Trade Organization, and deliberately looked the other way on a number of things that might have given us reason to restrict trade with China (currency manipulation in the 00s, various mercantilist policies, poor labor and environmental standards). As a result, the global economy underwent a titanic shift. Whereas global manufacturing, trading networks, and supply chains had once been dominated by the U.S., Japan, and Germany, China now came to occupy the central place in all of these:

As of 2021, China’s manufacturing output was equal to that of the U.S. and all of Europe combined.

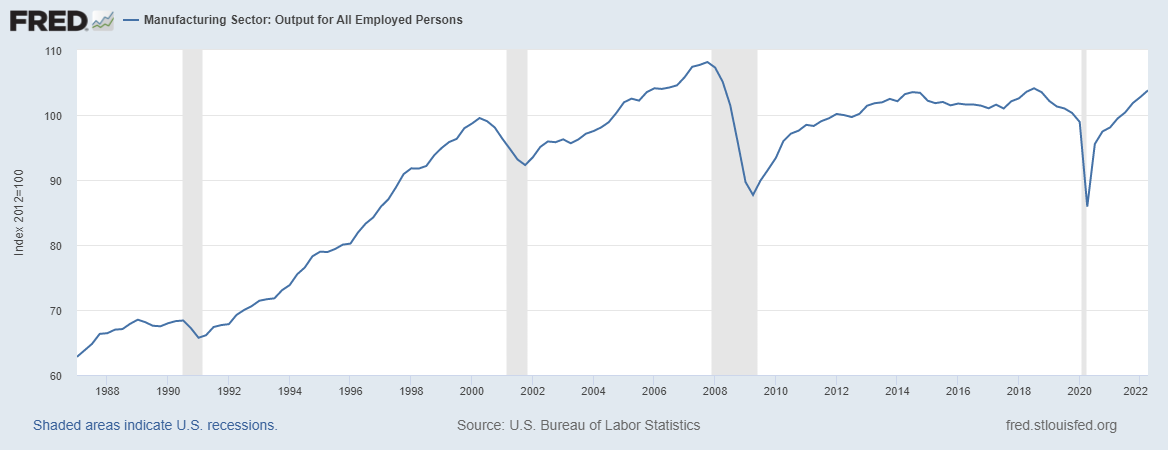

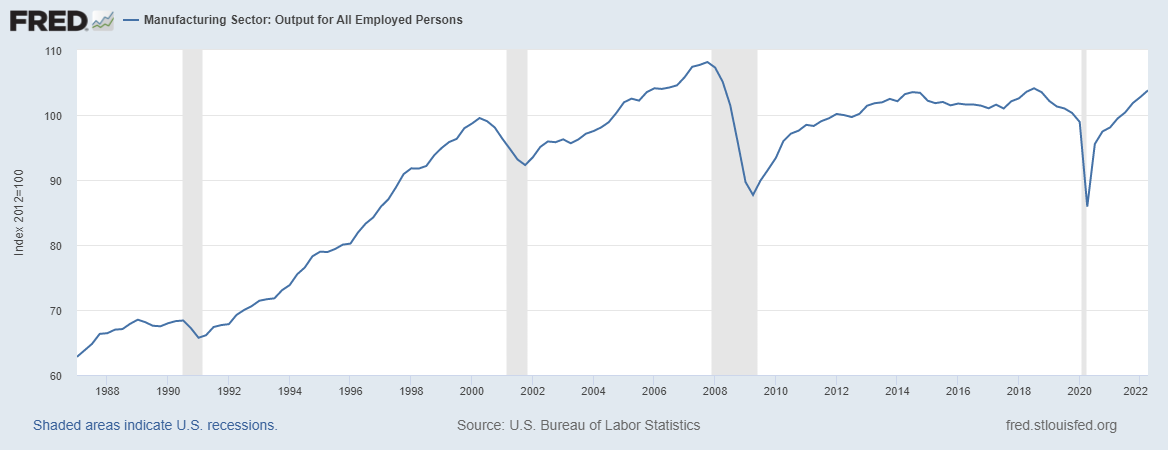

There were were always those who fretted about this shift, but too many people were just making too much money from it to upset the apple cart. U.S. manufacturers boosted their profits — and at least on paper, their productivity — by outsourcing production to China, while retail outlets (and consumers) benefitted from a flood of cheap imports. American companies grew their profits massively from grabbing mere slivers of the vast Chinese market, and salivated over the possibility of more. The finance industry reaped the benefits of cheap capital inflows as China bought U.S. assets in order to hold down the value of the RMB in the 2000s. Knowledge workers in the U.S. and Europe benefitted from researching, designing, and marketing the products that China built for us. Production workers in rich countries lost out big-time, but this was a price our country was willing to pay. America and our rich-world allies went from being the world’s workshop to being the world’s research park, and the people who had been our factory workers became the janitors and cooks and security guards of that research park.

This new system meant big compromises for China’s ruling elite as well. For decades they had closed off their society from foreign influences in an attempt to reorder it according to their liking, and opening up to global trade meant relinquishing some of the social control they had fought so hard for. An economy based on foreign direct investment meant a loss of economic control to foreign corporations. And occupying the low-value middle of the global supply chain — the assembly, processing, and packaging that requires enormous mobilization of resources but yields only modest profit margins — put China in danger of falling into the dreaded “middle income trap”.

But China was simply growing too fast to break this deal. Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao held firmly to the course Deng Xiaoping — who hand-picked them as his successors — had laid out for them. Economically, China pursued “reform and opening up”, while militarily and diplomatically it chose to “hide its strength and bide its time”.

Some called the world system of the 2000s and early 2010s “Chimerica”. During these years, the hope that global trade would lead to a cessation of great-power conflict, even without ideological alignment, seemed justified. And although China’s politics didn’t liberalize, under Jiang and Hu the country became more open to foreign travelers, foreign workers, and foreign ideas. This might not have been the End of History, but it was a compromise most people could live with for a while.

In the mid-2010s, this compromise began to break down. On the U.S. side, there was increasing anger over the long-term decline of good manufacturing jobs, and an increasing feeling of the U.S. in second place. China, and the Chimerica system, became the target of some of this anger — not without good reason. An increasingly thin, fraying elite consensus in favor of the system snapped when Donald Trump came to power. Trump slapped tariffs on China that raised prices slightly for U.S. consumers and manufacturers, but hurt China’s economy considerably more. The U.S. began to scrutinize and block Chinese investment a lot more under CFIUS, while export controls were put in place to strangle China’s flagship electronics company Huawei. U.S. imports from China shrank, eroding the bilateral trade deficit a bit:

Meanwhile, in China, Xi Jinping initiated a program to onshore the production of high-value intermediate goods, even as rising labor costs started to force some low-value labor-intensive assembly work to places like Vietnam or Bangladesh. Xi also shifted China’s industrial policy from a regional patchwork to a unified national effort. Foreign direct investment as a percent of China’s economy dropped under Xi:

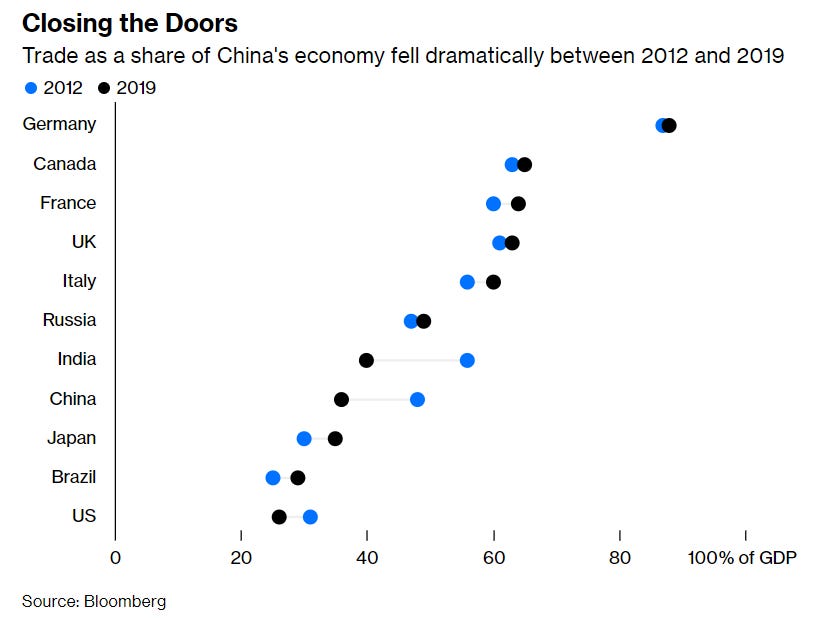

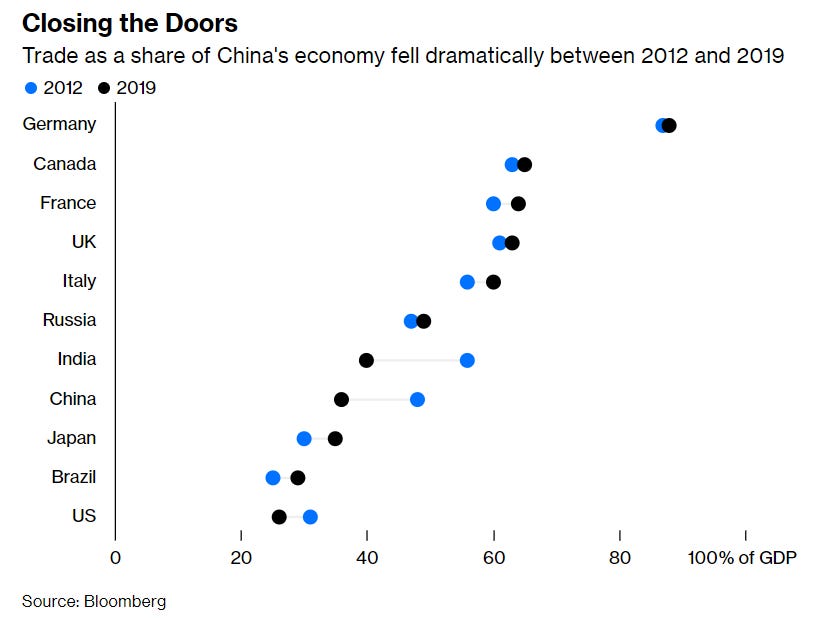

As Bloomberg’s David Fickling reports, trade became a smaller portion of China’s economy over this period:

And yet Chimerica would not be defeated so easily. U.S. imports from China, and the bilateral trade deficit, rebounded strongly in 2020-21 as a result of the Covid pandemic. The U.S. failed to increase manufacturing production at all under Trump, even as the economy grew quickly.

Meanwhile, despite an eroding cost advantage, China’s share of global manufacturing grew relentlessly:

U.S., European, and Asian companies were investing in China at a slightly slower rate, but this is partly because they had already moved so much of their production there. The country’s eroding cost advantage was more than cancelled out by the desire to grab a slightly larger sliver of the vast and growing Chinese market, the need to have factories located close to suppliers, and the country’s vast pool of well-trained process engineers — forces that economists collectively refer to as agglomeration effects. And rising costs and increasing government harassment and IP theft didn’t really make multinationals think about divesting; by the late 2010s, companies had simply become used to the idea that their manufacturing would be sourced from China. Making things in China was push-button, it was a no-brainer, it wasn’t something where you got out the Excel spreadsheet to figure out if it penciled. China was simply the “make-everything country”, so that is where you made things.

In other words, the vast and inevitable forces of economic agglomeration continued to dictate that China should be the world be the world’s workshop and America (and Europe and Japan) its research park. But there is one force in the global economy more powerful even than agglomeration: Great-power conflict.

In 2020 and 2021, a number of events convinced China’s leaders (and many observers in the U.S. and around the world) that China’s system had surpassed the U.S. in terms of economic vitality, political stability, and comprehensive national power. Most of these events were connected to the Covid pandemic. China’s ability to make simple goods like masks and Covid tests, coupled with the U.S.’ struggles in making these things, seemed to validate China’s positioning in the global supply chain. China’s ability to suppress the virus with non-pharmaceutical interventions seemed to demonstrate its higher state capacity. And U.S. unrest in 2020 and early 2021 seemed to suggest a society that was too internally divided to continue to play a central role on the world stage.

Xi Jinping, China’s leader, apparently felt that these events validated his pre-existing plan for “great changes unseen in a century” — i.e. China’s displacement of the U.S. as the global hegemon. Though this was Xi’s ambition from the start, it was the Chimerica system that had made his dream feasible, by making China the biggest manufacturing and trading nation on Earth.

Now, Xi seemed to feel that China had extracted all it could from the Chimerica system, and that the benefits no longer outweighed the costs. His industrial crackdowns in 2021 included measures to limit Western, Japanese, and South Korean cultural influences. Under his Zero Covid system, China became much more closed to the world, with inflows of people from abroad basically halted.

This is a big-think, “sweeping overview” sort of post. I find myself writing more of these recently, not because there aren’t little interesting news items or econ papers or debates to focus on, but because big things are happening very fast in the world right now, and I want to try and keep track of them.

After the end of the Cold War, the United States forged a new world. The driving, animating idea behind this new world was the belief that global trade integration would restrain international conflict. At first this rested on a Fukuyama-type “end of history” theory that political and economic liberalization would follow globalization, but as it became clear that various bureaucratic one-party oligarchies and petrostates (most notably China and Russia) were resistant to the end of history, the hopes for trade became more modest — at least countries that depended on each other economically would not fall into active conflict.

We didn’t just pay lip service to this theory; we bet the entire world on it. The U.S. and Europe championed the admission of China into the World Trade Organization, and deliberately looked the other way on a number of things that might have given us reason to restrict trade with China (currency manipulation in the 00s, various mercantilist policies, poor labor and environmental standards). As a result, the global economy underwent a titanic shift. Whereas global manufacturing, trading networks, and supply chains had once been dominated by the U.S., Japan, and Germany, China now came to occupy the central place in all of these:

As of 2021, China’s manufacturing output was equal to that of the U.S. and all of Europe combined.

There were were always those who fretted about this shift, but too many people were just making too much money from it to upset the apple cart. U.S. manufacturers boosted their profits — and at least on paper, their productivity — by outsourcing production to China, while retail outlets (and consumers) benefitted from a flood of cheap imports. American companies grew their profits massively from grabbing mere slivers of the vast Chinese market, and salivated over the possibility of more. The finance industry reaped the benefits of cheap capital inflows as China bought U.S. assets in order to hold down the value of the RMB in the 2000s. Knowledge workers in the U.S. and Europe benefitted from researching, designing, and marketing the products that China built for us. Production workers in rich countries lost out big-time, but this was a price our country was willing to pay. America and our rich-world allies went from being the world’s workshop to being the world’s research park, and the people who had been our factory workers became the janitors and cooks and security guards of that research park.

This new system meant big compromises for China’s ruling elite as well. For decades they had closed off their society from foreign influences in an attempt to reorder it according to their liking, and opening up to global trade meant relinquishing some of the social control they had fought so hard for. An economy based on foreign direct investment meant a loss of economic control to foreign corporations. And occupying the low-value middle of the global supply chain — the assembly, processing, and packaging that requires enormous mobilization of resources but yields only modest profit margins — put China in danger of falling into the dreaded “middle income trap”.

But China was simply growing too fast to break this deal. Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao held firmly to the course Deng Xiaoping — who hand-picked them as his successors — had laid out for them. Economically, China pursued “reform and opening up”, while militarily and diplomatically it chose to “hide its strength and bide its time”.

Some called the world system of the 2000s and early 2010s “Chimerica”. During these years, the hope that global trade would lead to a cessation of great-power conflict, even without ideological alignment, seemed justified. And although China’s politics didn’t liberalize, under Jiang and Hu the country became more open to foreign travelers, foreign workers, and foreign ideas. This might not have been the End of History, but it was a compromise most people could live with for a while.

In the mid-2010s, this compromise began to break down. On the U.S. side, there was increasing anger over the long-term decline of good manufacturing jobs, and an increasing feeling of the U.S. in second place. China, and the Chimerica system, became the target of some of this anger — not without good reason. An increasingly thin, fraying elite consensus in favor of the system snapped when Donald Trump came to power. Trump slapped tariffs on China that raised prices slightly for U.S. consumers and manufacturers, but hurt China’s economy considerably more. The U.S. began to scrutinize and block Chinese investment a lot more under CFIUS, while export controls were put in place to strangle China’s flagship electronics company Huawei. U.S. imports from China shrank, eroding the bilateral trade deficit a bit:

Meanwhile, in China, Xi Jinping initiated a program to onshore the production of high-value intermediate goods, even as rising labor costs started to force some low-value labor-intensive assembly work to places like Vietnam or Bangladesh. Xi also shifted China’s industrial policy from a regional patchwork to a unified national effort. Foreign direct investment as a percent of China’s economy dropped under Xi:

As Bloomberg’s David Fickling reports, trade became a smaller portion of China’s economy over this period:

And yet Chimerica would not be defeated so easily. U.S. imports from China, and the bilateral trade deficit, rebounded strongly in 2020-21 as a result of the Covid pandemic. The U.S. failed to increase manufacturing production at all under Trump, even as the economy grew quickly.

Meanwhile, despite an eroding cost advantage, China’s share of global manufacturing grew relentlessly:

U.S., European, and Asian companies were investing in China at a slightly slower rate, but this is partly because they had already moved so much of their production there. The country’s eroding cost advantage was more than cancelled out by the desire to grab a slightly larger sliver of the vast and growing Chinese market, the need to have factories located close to suppliers, and the country’s vast pool of well-trained process engineers — forces that economists collectively refer to as agglomeration effects. And rising costs and increasing government harassment and IP theft didn’t really make multinationals think about divesting; by the late 2010s, companies had simply become used to the idea that their manufacturing would be sourced from China. Making things in China was push-button, it was a no-brainer, it wasn’t something where you got out the Excel spreadsheet to figure out if it penciled. China was simply the “make-everything country”, so that is where you made things.

In other words, the vast and inevitable forces of economic agglomeration continued to dictate that China should be the world be the world’s workshop and America (and Europe and Japan) its research park. But there is one force in the global economy more powerful even than agglomeration: Great-power conflict.

In 2020 and 2021, a number of events convinced China’s leaders (and many observers in the U.S. and around the world) that China’s system had surpassed the U.S. in terms of economic vitality, political stability, and comprehensive national power. Most of these events were connected to the Covid pandemic. China’s ability to make simple goods like masks and Covid tests, coupled with the U.S.’ struggles in making these things, seemed to validate China’s positioning in the global supply chain. China’s ability to suppress the virus with non-pharmaceutical interventions seemed to demonstrate its higher state capacity. And U.S. unrest in 2020 and early 2021 seemed to suggest a society that was too internally divided to continue to play a central role on the world stage.

Xi Jinping, China’s leader, apparently felt that these events validated his pre-existing plan for “great changes unseen in a century” — i.e. China’s displacement of the U.S. as the global hegemon. Though this was Xi’s ambition from the start, it was the Chimerica system that had made his dream feasible, by making China the biggest manufacturing and trading nation on Earth.

Now, Xi seemed to feel that China had extracted all it could from the Chimerica system, and that the benefits no longer outweighed the costs. His industrial crackdowns in 2021 included measures to limit Western, Japanese, and South Korean cultural influences. Under his Zero Covid system, China became much more closed to the world, with inflows of people from abroad basically halted.