The Secret History of Bigfoot and the CIA

Intelligence agencies employ myriad types of cover for action, including the hunt for the mysterious creatures like the Abominable Snowman

The Secret History of Bigfoot and the CIA

Intelligence agencies employ myriad types of cover for action, including the hunt for the mysterious creatures like the Abominable Snowman

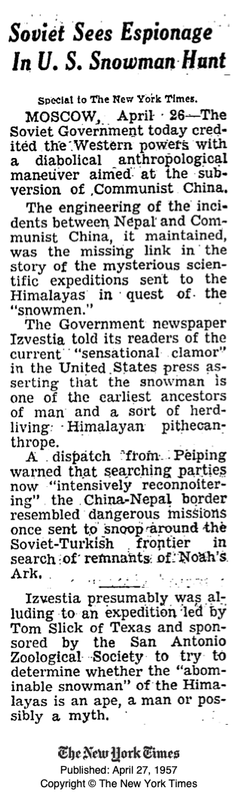

John SchindlerTensions are rising in East Asia, to a possible point of no peaceful return. Last week, this newsletter described how alarmed U.S. senior intelligence officials have grown regarding the threat of war with China over the Taiwan issue. Now, Tokyo’s just-issued 2023 defense white paper sounds the alarm, depictingJapan’s security environment as “the most severe and complex” since the Second World War, thanks to increasing Chinese willingness to employ military power to achieve Beijing’s strategic aims. Since the United States has a mutual defense pact with our close ally Japan, Americans need to take Tokyo’s fast-rising threat perception seriously.

On the other side, the Chinese Communist Party considers itself the responsible ones, merely looking out for their country’s defense and self-interest in a dangerous world. After all, Japan invaded China in 1931, and even more in 1937, not the other way around. This week, Chinese top officials were in Pyongyang to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the end of the Korean War (Russia’s defense minister Sergei Shoigu was also prominently in attendance), hailed by the CCP as a “victory for peace.” That bloody war, nearly forgotten among Americans, remains a vivid memory for Beijing, which views its participation in defense of North Korea as a necessary response to U.S. aggression.

Even fewer Americans recall that Washington wasn’t merely fighting China in Korea in the 1950s. The CCP, however, regularly reminds the Chinese people of this complex story, which is mostly about American spies and covert action trying to stymie the new Communist regime from its beginnings. From the birth of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949, after the conclusion of that country’s long-running civil war (which saw the losers retreat to sanctuary on Taiwan), the Central Intelligence Agency tried hard to run agents inside the PRC, frequently without success. Indeed, the first CIA officer killed in the line of duty, Douglas Mackiernan, died while trying to escape China in 1950, two months before the outbreak of the Korean War. In a screw-up, Mackiernan, who had been working undercover in Xinjiang to purloin Soviet and Chinese secrets, particularly regarding nuclear weapons, was shot by Tibetans by mistake.

That’s a painful irony, given how much effort CIA expended trying to assist Tibetans after their ancient country was occupied by the People’s Liberation Army in October 1950 and forcibly taken under Beijing’s control. Tibetan resistance to the PLA didn’t end with the CCP’s occupation. Instead, an insurgency developed inside Tibet that by 1957 was big enough that Washington took notice and decided to support it clandestinely, led by the CIA, with help from the Pentagon. That secret war remained hidden for decades, and much of its operations remain classified, yet Washington has released enough information that the essential story can be told.

Langley’s secret Tibetan program ran from 1957 until 1969, although it wasn’t completely shut down until President Richard Nixon’s opening to Beijing in the early 1970s, which made CIA’s support to the Tibetan resistance obsolete. From that point, Washington viewed the PRC as its partner in the Cold War against the Soviet Union. However, for a dozen years, American spies employed the full range of covert action, from paramilitary operations to propaganda to conventional espionage against China, in this effort to bolster Tibetan resistance to Beijing.

Although Tibetans paid most of that price, something the few surviving elderly veterans of that secret war now discuss with pride, the CIA’s campaign was broadly a success in American eyes. While clandestine support for the Tibetan resistance ultimately failed to endanger Chinese rule, these CIA operations behind Communist lines proved more successful than they were elsewhere, for instance in Ukraine or Albania, where CIA airdrops of weapons and fighters behind Communist lines were routinely intercepted by Red counterintelligence, usually fast. Moreover, Langley’s clandestine activities in Tibet kept alive the spirit of Tibetan independence, which in a sense has never waned, thanks in no small part to the role played by the 14th Dalai Lama, who escaped to India in 1959 with CIA’s help: the Dalai Lama’s brother had a close relationship with the agency, which rescued the spiritual leader from China’s clutches. Tibet’s government-in-exile has operated from India, a thorn in Beijing’s side, ever since 1959, under the Dalai Lama’s patronage.

CIA’s support to the Tibetan resistance took the customary early Cold War form. Agency paramilitary specialists trained Tibetan fighters in secret – first on the island of Saipan, then at Camp Hale in Colorado – then inserted them and weapons into Tibet via CIA airdrops. Within a few years it was apparent that parachute insertion of personnel and armaments wasn’t generating much impact on the ground in occupied Tibet, so CIA established a clandestine base in the Mustang region of Nepal, on the Tibetan border. From Mustang, Tibetan fighters were supposed to infiltrate into Chinese-occupied territory and create trouble for the PLA. This failed to materialize on any large scale, leading to the shutdown of CIA’s Mustang base in 1969. Challenges were many: the forbidding Himalayan terrain, sometimes inadequate logistical support from Langley, the political complications of Nepalese neutrality, plus Chinese counterintelligence vigilance.

Nevertheless, these clandestine operations, even when unsuccessful, maintained pressure on Beijing in the Cold War and kept hope alive for Tibetans seeking to throw off the Communist yoke. Particularly in its early years, CIA’s Tibetan program seemed like a solid return on investment for Washington. This secret story, hidden from view until after the Cold War’s end, employed a colorful cast of characters befitting its exotic venue.

Enter Peter Byrne, who died this week at the age of 97. The Irish-born Byrne served in the Royal Air Force in the Second World War and thereafter became an exotic full-time adventurer, a big game hunter in India and Nepal. However, Byrne ultimately spent most of his life in the United States, specifically in the Pacific Northwest, becoming for a time the best-known Bigfoot hunter in the world. Whether or not that elusive manlike monster exists, Byrne made a living off attempting to find Bigfoot, running various expeditions for different wealthy benefactors, with as much press attention as Byrne could muster. In his 1970s heyday, Byrne represented much of the public face of the Bigfoot mania which, like the Bermuda Triangle, featured prominently in that decade’s popular imagination.