damn, I couldn't find a source for that video and the split looks wider than ones shown in previous videos.You really believe this fake ass video from a Russia supporting troll account?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Thousands feared dead in 7.8 magnitude earthquake in Turkey

- Thread starter Elim Garak

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?

Turkish journalists detained over earthquake reports

Press freedom groups criticise a new "disinformation law" used to target reporting on the disaster.

Turkish journalists detained over earthquake reports

- Published

8 hours ago

- Published

- Turkey–Syria earthquakes 2023

IMAGE SOURCE,MIR ALI KOÇER'S PERSONAL ARCHIVE

Image caption,

Mir Ali Koçer says he was traumatised by covering the earthquake's aftermath

By Grigor Atanesian and Nihan Kalle

Global Disinformation Team and BBC Monitoring

Freelance journalist Mir Ali Koçer was 200 miles from the epicentre when Turkey was struck by a deadly earthquake on 6 February. Grabbing his camera and microphone, he drove down to the affected region to interview survivors.

He shared stories of survivors and rescuers on Twitter and is now under investigation on suspicion of spreading "fake news" and could face up to three years in jail.

He is one of at least four journalists being investigated for reporting or commenting on the earthquake.

Press freedom groups say dozens more have been detained, harassed or prevented from reporting.

At least 50,000 people were killed when earthquakes hit both Turkey and Syria.

Turkey's authorities have not commented on the detentions.

'I couldn't hold back my tears'

On the night of the earthquake, Mr Koçer - who is Kurdish and contributes to pro-opposition news sites such as Bianet and Duvar - was smoking on his balcony in the south-eastern city of Diyarbakir, when his two dogs suddenly started barking.He later remembered how they had barked just like that in 2020, seconds before a smaller earthquake hit eastern Turkey.

"I felt I was shaking. I felt the house shaking, I felt the TV shaking," says Mr Koçer. He hid under a dinner table with the dogs and then rushed outside.

Mr Koçer left Diyarbakir and drove to the city of Gaziantep. He was shocked by scenes of destruction and victims enduing freezing temperatures in towns near the very epicentre of the quake.

At least 3,000 of the earthquake's victims died in Gaziantep.

"When holding the microphone, behind the camera or in front of the camera, I could not hold back my tears," Mr Koçer recalls.

'Provocateurs'

IMAGE SOURCE,TURKISH PRESIDENCY

Image caption,

President Erdogan promised he would rebuild cities

Mr Koçer was touched by the influx of volunteers and rescue teams coming from Western Turkey, and he shared their stories on Twitter. Some of the survivors told him they received no aid for days. Similar complaints were cited across pro-opposition media outlets.

Visiting the earthquake-affected areas, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan told the people he would rebuild their cities. But he also warned that those spreading "fake news" and "causing social chaos" would be prosecuted, calling them "provocateurs".

Mr Koçer says that while he was reporting from the region hit by the earthquake, Diyarbakir police left a note at his apartment, instructing him to visit the police station and give a statement.

- Scammers profit from Turkey-Syria earthquake

Turkey's new law was adopted in October. It criminalised the public spreading of disinformation and gave the state much broader powers to control news sites and social media.

The Venice Commission, a legal watchdog of the Council of Europe, said the law would interfere with freedom of expression.

Opposition parties call it a "censorship law".

'They don't like criticism'

Mr Koçer insists that he was meticulous in his work and interviewed all sides, from survivors to the police, the gendarmerie and rescue workers. "I did not share information without thorough research and analysis," he says.Reporters Without Borders (RSF) called the investigation against Mr Koçer "absurd" and urged the authorities to drop it.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), an advocacy group, at least three more journalists are facing criminal charges.

Merdan Yanardağ and Enver Aysever are prominent Istanbul-based political commentators with large social media followings. Both have criticised the government's rescue efforts. They're both under investigation along with Mehmet Güleş, who, like Mr Koçer, is based in Diyarbakir. He was detained on suspicion of "inciting hatred" for interviewing a volunteer critical of the government's rescue effort and later released, according to RSF.

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS

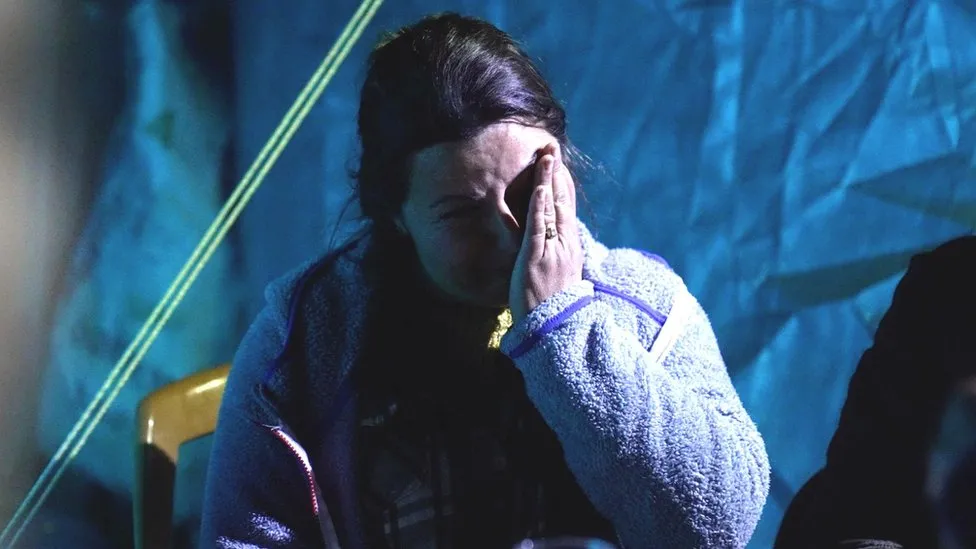

Image caption,

Agony in Diyarbakir after the earthquake

The number of other journalists under investigation is unclear. On Tuesday, the police said they detained 134 people over "provocative posts" and arrested 25 of them, but their identities have not been disclosed. Some of those detained may well have been spreading falsehoods, including one that Afghan migrants had been scavenging in ruined neighbourhoods.

But critics say the clampdown has gone far beyond those spreading harmful disinformation.

"The government is trying to suppress information coming from the quake zone," says cyber rights expert Yaman Akdeniz who teaches at the Istanbul Bilgi University.

The arrests came after Turkey's presidential communications director warned against "lethal disinformation" jeopardising the rescue efforts. The directorate also rolled out a smartphone app called "Disinformation Reporting Service" encouraging people to report manipulative posts about the quake.

"Any time [Turkish] officials and the government are being criticised, they don't like it," says Arzu Geybulla, a journalist in Istanbul covering digital authoritarianism and censorship.

"But this time they are perhaps more vocal."

The BBC contacted Turkey's presidential directorate for communications asking about the journalists investigated and the calls by advocacy groups to drop investigations, but has had no response.

Turkey earthquake: Survivors living in fear on streets

Train carriages, volleyball courts and public roads - families now find shelter wherever they can.

Turkey earthquake: Survivors living in fear on streets

Published

14 hours ago

Turkey–Syria earthquakes 2023

Songul Yucesoy's home was destroyed when a 6.4 magnitude earthquake struck a month ago

By Anna Foster

BBC News, Samandag, southern Turkey

Songul Yucesoy carefully washes her dishes, soaping the plates and cutlery before rinsing off the bubbles and laying them out to dry. An unremarkable scene, except she's outdoors, sitting in the shadow of her ruined house.

It tilts at an alarming angle, the window frames are hanging out and there's a large chunk of the rusty iron roof now resting in the garden.

It is a month since the devastating earthquakes in Turkey and Syria - with officials putting the number of deaths in Turkey alone at 45,968. In Syria, more than 6,000 are known to have lost their lives.

Those who survived face an uncertain future. One of their most serious problems is finding somewhere safe to live. At least 1.5 million people are now homeless, and it's unclear how long it will take to find them proper shelter.

The Turkish disaster agency Afad, meanwhile, says almost two million people have now left the quake zone. Some are living with friends or loved ones elsewhere in the country. Flights and trains out of the region are free to those who want to leave.

But in the town of Samandag, near the Mediterranean coast, Songul is clear that she and her family aren't going anywhere. "This is very important for us. Whatever happens next - even if the house falls down - we will stay here. This is our home, our nest. Everything we have is here. We are not going to leave."

The deadly quake destroyed properties in the region, leaving thousands of families homeless

Tents have appeared everywhere in the town of Samandag, but more are needed

Precious pieces of furniture have been carefully pulled from the house and set up outside. On top of a polished wooden side table is a holiday souvenir, a picture made of shells from the Turkish resort of Kusadasi. There's a bowl of fruit, with white mould creeping across a large orange. Things that look normal indoors feel strange and out of place when they're sitting in the street.

Right now, the whole family is living in three tents just a few steps away from their damaged home. They sleep and eat there, sharing food cooked on a small camping stove. There's no proper toilet, although they've recovered one from the bathroom and are trying to plumb it in in a makeshift wooden shed. They've even created a small shower area. But it's all very basic, and the lack of space and privacy is obvious. These tents are cramped and overcrowded.

It's been an agonising month for Songul. Seventeen of their relatives were killed in the quake. Her sister Tulay is officially missing. "We don't know if she is still under the rubble," she tells me. "We don't know whether her body was taken out yet or not. We're waiting. We can't start mourning. We can't even find our lost one."

People are sleeping on seats in train carriages in the port city of Iskenderun

Songul's brother-in-law Husemettin and 11-year-old nephew Lozan died when their apartment building in Iskenderun collapsed around them as they slept. We visited what was left of their home, a sprawling pile of twisted debris. Neighbours told us three blocks of flats had fallen.

"We brought Lozan's body here," Songul says quietly. "We took him from the morgue and buried him close to us in Samandag. Husemettin was buried in the cemetery of the anonymous, we found his name there."

A picture of the family smiles out of Tulay's still-active Facebook profile, their arms around each other, faces close. Lozan holds a red balloon tightly.

The homelessness crisis created by the quake is so acute because of the real shortage of safe spaces that are left standing. More than 160,000 buildings collapsed or were badly damaged. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimates at least 1.5 million people are still inside the quake zone, but with nowhere to live. It's hard to know the real figure, and it could be far higher.

Study cabins are arriving, but too slowly. Tents have appeared everywhere, from sprawling new encampments to individual ones dotted amidst the rubble. There still aren't enough. News that the Turkish Red Crescent had sold some of its stock of taxpayer-funded tents to a charity group - albeit at cost price - led to frustration and anger.

In some cities, people are still living inside public buildings.

IMAGE SOURCE,ANNA FOSTER/BBC

Families are sharing tents together, weeks after the disaster

In Adana, I met families sleeping on blankets and mattresses spread across a volleyball court. In the port city of Iskenderun they have made their home on two trains parked at the railway station. Seats have become beds, luggage racks are filled with personal possessions and the staff there try hard to keep things clean and tidy. Tears fill the eyes of one young girl as she hugs a pillow instead of a teddy bear. This isn't home.

Songul's children are struggling, too. Toys and games are stuck inside dangerous houses, and there's no school. "They're bored, there's nothing to keep them busy. They just sit around. They play with their phones, then go to bed early once they run out of charge."

When night falls, things are even harder. There's no electricity in Samandag now. Songul has draped colourful solar lights across their white tent, just above the bold UNHCR logo. Homeless in their own country, they're not refugees, but they've still lost everything.

Songul says her family now live in fear, with aftershocks often keeping them awake overnight

"I put the lamps here to be seen," Songul explains. "We're scared when it gets dark. Having no power is a big problem. The fear is too big, and all night long we feel the aftershocks, so it's hard to sleep." Starting to cry, she wipes away the tears with her hand.

"We are free people, we are used to freedom, independence, everyone living in their own houses," adds her husband, Savas. "But now we are three families, eating in one tent, living and sitting in one single tent."

"This is all new to us, we don't know what the future holds. And there's always the fear. Our houses have collapsed, what will happen next? We just don't know."