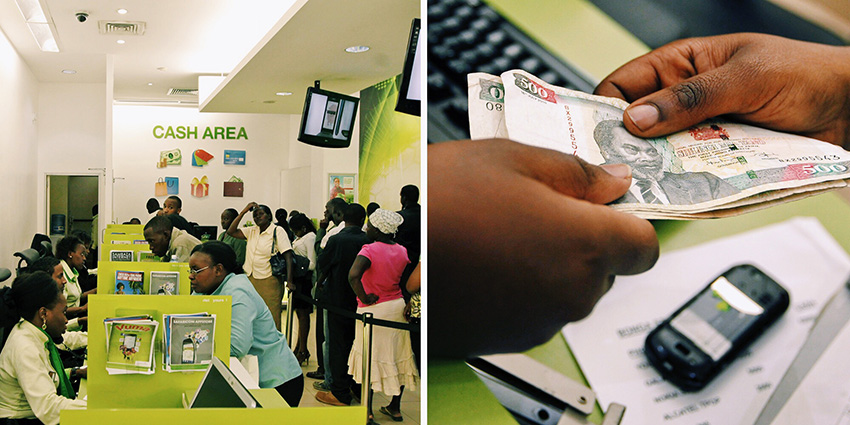

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Noor Khamis/Reuters.

7 The Mobile Wallet

Cash is king, the saying goes. But it’s actually something of a curse in many parts of the world. A horribly inefficient and often dangerous means of storing value and exchange, coins and bills can easily be stolen, or lost, or destroyed in a fire. “Cash is the most formidable enemy of the poor,” Tonny K. Omwansa and Nicholas P. Sullivan write in their 2012 e-book Money, Real Quick, which chronicles the heartening rise of M-Pesa, a new system that’s bringing secure payments and money storage to millions of new consumers.

For the world’s wealthy, cash has long been free from its metal and paper incarnations. The global network of banks and payment processors is wired to zap cash electronically around the world. But Visa, MasterCard, and global banks like HSBC and JPMorgan Chase are expensive wired systems that are actually quite sluggish. While you can conduct your transactions wirelessly, money still moves through a complex network of brick-and-mortar banks and hard-wired terminals. And that can’t possibly accommodate the needs of most of humanity.

In the U.S., innovative services like Google Wallet, Square, and retailers’ payment apps—all of which basically sync prepaid cards or debit cards to mobile devices—haven’t made much headway. “After years of effort, just $3.1 billion in purchases came from mobile wallets last year, according to Javelin Strategy,” asFortune noted earlier this year. Research firm eMarketer reported that “proximity payment transaction values”—commerce done by readinga smartphone, for example—totaled an estimated $1.6 billion in 2013.Venmo, an app that allows people to send cash to one another instantly, is gaining some traction.

Square, Google Wallet, Venmo.

Photos by Shardayyy/Flickr Creative Commons, Google, and Venmo

But it’s small change. Along with broadband speed, mobile payments are another technology area in which the U.S. lags badly behind global standards. Only this time, we don’t trail the advanced economies of Scandinavia. Rather, the standard for simplicity and efficacy is being set in an impoverished country: Kenya. The mobile phone company Safaricom introduced M-Pesa in the fertile and remote Great Rift Valley seven years ago. The all-wireless system, which allows people to send and receive cash with the same reliability, ease, and low cost as they can send SMS texts, has grown quickly from startup to national standard. Vodafone, the telecommunications giant that owns 40 percent of Safaricom, estimates that M-Pesa has some 18 million customers, most of them in Kenya. In a typical year, transactions worth about 20 percent of Kenya’s GDP are processed by the system. In the U.S., that would be equal to more than $3 trillion. In recent years, a great deal of financial innovation—structured mortgages, tax-avoidance strategies—have generally benefited the already comfortable. M-Pesa and its growing number of peers in the developing world stand out, however, for their ability to provide a remarkably valuable service to consumers whose needs have long been ignored. They don’t simply liberate money from its physical manifestation; they’ve shown the potential to liberate people from some of the shackles of poverty. And that’s what makes these mobile payment systems a wonder of the modern world.

Customers queue for mobile money transfers, known as M-Pesa, inside a Safaricom office in Nairobi, Kenya, on July 15, 2013.

Photo by Thomas Mukoya/Reuters

M-Pesa and its imitators have thrived in part by freeing exchange from the expensive, inaccessible physical networks and infrastructure that have heretofore confined money. (Other services include Telenor’s Easypaisa in Pakistan, Smart Money in the Philippines, and True Move in Thailand.) “There’s been no innovation in paper notes and cash for 2,600 years,” says Tim Harrabin, senior adviser to Analysys Mason and an expert on mobile payments. “The mobile payment system is about replacing notes and coins and enabling people to move money.” Instead of replicating the developed world’s financial system, M-Pesa leapfrogs it. And it does so by marrying Kenya’s abundant human capital to systems that have proven to thrive in the harsh environment of sub-Saharan networks.

Banks, which have been around for many centuries, represent one of the most obvious examples of the failure of trickle-down economics. They were founded to serve the rich. And today, about 2.5 billion adults—half of those on the planet—are estimated to be unbanked. In Kenya in 2006, fewer than 20 percent of the people had bank accounts. “In 115 years, banks provided their customers with 43 licensed commercial banks, 1,045 bank branches, and 1,500 ATMs,” write Omwansa and Sullivan. This, in a country with a population of 40 million. Only about 100,000 people had credit or debit cards. “If you look at the emerging market, there’s a huge lack of infrastructure. There are no banks, there are no bank branches. There are no real financial services in the rural areas,” Michael Joseph, the South Africa–born former CEO of Safaricom who helped create M-Pesa, tells me. “But the needs for the things that banks provide—safe place to store money, someone to process transactions—were certainly there.”

In contrast to banking, mobile telephony has diffused rapidly from a plaything of the elites to a mainstay of the masses. According to the International Telecommunication Union, this year there were to be nearly 7 billion wireless phones in the world, “corresponding to a penetration rate of 96 percent.” In Africa, some 60 percent of people have mobile phones.

A man works in his cellphone repair shop near a busy street market on Nov. 18, 2007, in Ghana.

Photo by Shaul Schwarz/Getty Images

This gaping chasm between the number of people with phones and those with bank accounts provided an opening, but not for a bank. Safaricom dominated Kenya’s mobile market. As part of an effort to keep subscribers from switching, it decided to offer a new service that would allow people to send and receive money through their phones.

Safaricom modeled M-Pesa in part on the ancient system of Hawalah, in which trusted intermediaries function as money transfer agents. “It replicates exactly what Hawalah does, but it’s more formalized,” says Joseph, who is now director of mobile money at Vodafone.

Here’s how it works. A mobile phone subscriber registers with a local agent—often the same person who sells airtime or SIM cards—by showing her national identification card. She gives money to the agent, who transforms the cash into electronic money via a series of SMS texts. The agent puts the cash in her account, which is in turn held in a centralized bank account. Once the cash is loaded, the customer can use her phone like a debit card (paying people via SMS), or like a card reader (receiving payments via SMS), or like an ATM card (turning electronic money into cash at outposts run by agents)—but without the high fees typically inherent in those transactions. (There’s no charge for uploading money, but there is one of about 1 percent for getting cash.)

In a country where a bank branch could be a day’s walk away, where sending a remittance might mean giving cash to a bus driver and hoping he delivers it, M-Pesa was something like a godsend. When the mobile payment system launched in March 2007, Joseph says the company expected to enroll a few hundred thousand people in its first year. After 12 months, 2 million people had signed up. The company expanded the service to Tanzania, Mozambique, and India, and it continued to attract users in Kenya. Now M-Pesa says it has about 17 million customers who move about $1.5 billion through the system each month—a remarkable level of penetration.

What makes it work? M-Pesa’s genius is in the simplicity of the design the business model, and the ability to avoid the heavy and expensive infrastructure associated with other payments systems. Customers have two PINs—one for their phones, one for M-Pesa. Each transaction is conducted via an encrypted SMS that runs through M-Pesa’s mobile money platform. Users receive confirmations by text and can get their balance and transaction histories.

A true mobile payment system like M-Pesa offers several advantages over debit card systems. Mobile phone operators in emerging markets already have a network of low-cost distribution points where people can gain access to cash—the agents who sell airtime and SIM cards. M-Pesa has recruited 160,000 agents in Kenya. So even in rural areas, people are never too far from access to the service. The screen of a phone is much more information-rich than, say, a debit card. Unlike debit cards, M-Pesa lets people send money directly to other people. And it can be used by people who don’t need equipment or infrastructure other than their mobile phones.

M-Pesa in Iringa, Tanzania.

Photo by Brian Harries/Flickr Creative Commons

M-Pesa is much faster, too. Unlike credit and debit card systems, which may take a few days to settle transactions, M-Pesa moves money instantaneously. Visa and other electronic payments systems we use are much more complicated: They must be processed by hard-wired terminals and involve cardholders, merchants, issuing banks, and processors, not to mention the transaction fees that can often amount to 2 or 3 percent of every transaction. M-Pesa is also quite safe. “We’ve been operating seven years, and have had many millions of transactions,” says Joseph. “To date, we have not had any hacking or anything like that.”

M-Pesa originally targeted Nairobi’s higher-income men, who would use the system to send money to relatives in villages. But urban shopkeepers and rural farmers have picked up on it. Originally designed as a peer-to-peer network, M-Pesa has evolved into a commercial tool. Coca-Cola’s Kenya distributor uses M-Pesa to accept payments from its network of vendors. Well-off people use M-Pesa to pay their domestic staff. As Omwansa and Sullivan note in Money, Real Quick, the Mumias Sugar Company uses M-Pesa to pay many of its cane cutters instantly. (Previously, they’d have to line up for hours to get paid and miss work as a result.) The company has also done deals with banks that allow people to set up savings accounts through M-Pesa and save in increments of as little as a few pennies.

A man sends money through M-Pesa in Nairobi in 2007.

Photo by Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty Images

In countries where a great deal of economic activity takes place in the shadows, M-Pesa and its rivals have had the effect of bringing more economic activity on the books. Money simply moves more quickly and efficiently throughout the economy when it travels via SMS. While traditional banking dwarfs this sector, the potential is immense. And that’s in large measure because payment innovations are simultaneously benefiting the wealthy, who move cash in big chunks through services like bitcoin or Apple Pay, and the massive numbers of poor people, who move cash in small increments.

Currency systems are circles of trust. So as these mobile payment systems trickle down and rise up, they’re likely to gain more momentum, abetted not just by those without access to traditional banks but by the those who are looking for excuses to avoid them following the financial crisis. Just as the exchange of digital information has boosted productivity and growth sharply, so, too, can the exchange of digital money. Imagine if India were able to deliver social-welfare benefits through digital cash and not through agents who might pilfer the aid. Imagine how much more effective tax collection would be in Italy and Greece if traceable mobile payments replaced cash. Imagine how crime might fall around the world if people in dangerous neighborhoods stopped stuffing money under their mattresses. Imagine how migrant workers would increase their effective wages simply by sending money home via text rather than through expensive money transfer services.

Too frequently, digital technology has been a force for the expansion of global income inequality. By enabling cheap phones to send small bits of cash at very cheap rates, mobile payment systems won’t take anything away from the haves. But they may give something quite valuable to the have-nots.

Check back next week for our final modern wonder.

Daniel Gross is a longtime Slate contributor. His most recent book is Better, Stronger, Faster. Follow him on Twitter.