Two Women Joined GM More Than a Decade Ago. Their Futures Couldn’t Be More Different

Tentative labor deal aside, the transition to electric and autonomous vehicles is leaving a generation of workers behind.

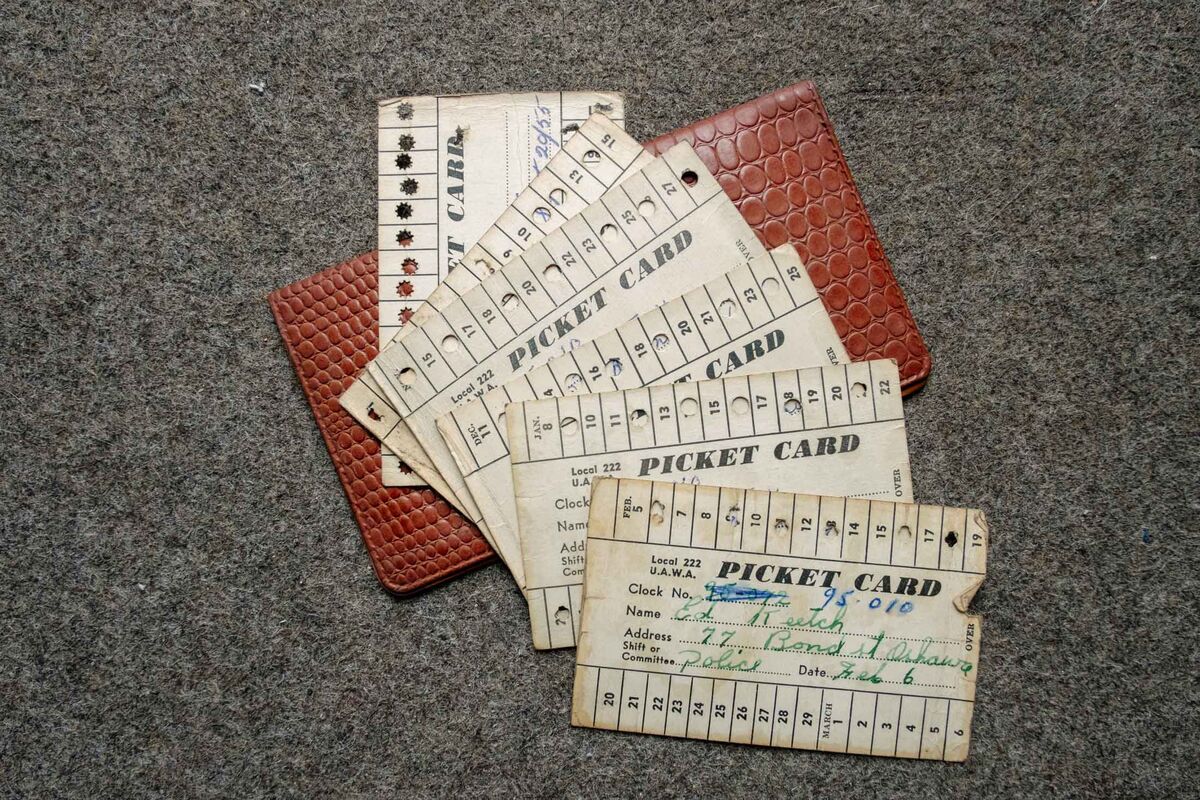

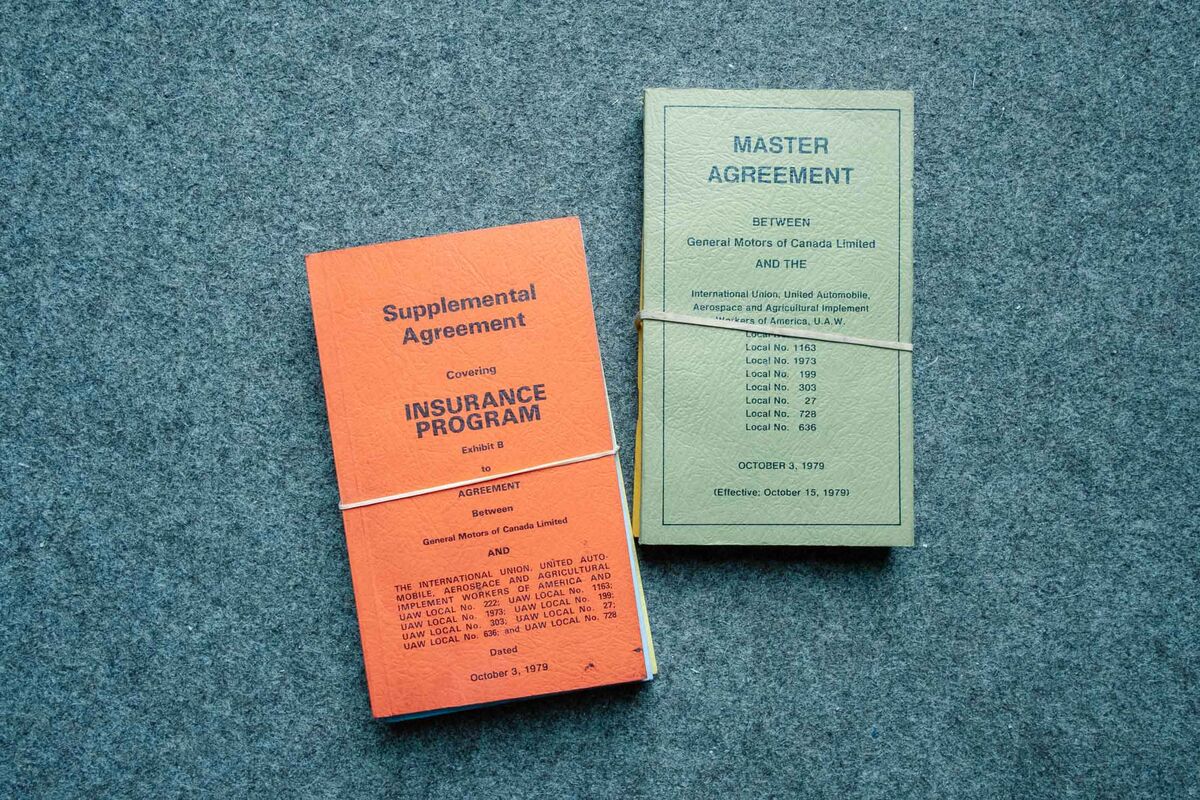

Rebecca Keetch, a GM production operator, looks at the ephemera her grandfather kept from the family’s time at GM, in Oshawa, Ontario, July 2019.

PHOTOGRAPHER: LAURENCE BUTET-ROCH FOR BLOOMBERG

Amanda Kalhous and Rebecca Keetch joined General Motors Canada within a year of each other. Over the past 15 years, they’ve survived layoffs, a government bailout, and the company’s bankruptcy. Today, they’re living through something more fundamental: the biggest shift the auto industry has seen since the invention of the assembly line.

This time, only one of them has a future in it.

In any other generation, the thousands of employees being laid off by GM in Oshawa, Ontario, could easily be retrained for work elsewhere in the sector. But hard work and a solid education are no longer enough to hold onto a job in an industry that technology is upending.

GM knows what it needs to secure its future, and it’s not Rebecca, a production operator at the Oshawa factory with a community college diploma, plus 18 months of university, who places two belts on an engine every 108 seconds. It’s Amanda, an electrical engineer with two university degrees and 24 patents to her name who oversees a team that designs software for the next generation of vehicles.

Mary Barra, chief executive officer of General Motors Co., is gambling that climate change and urbanization is about to accelerate the shift to electric and autonomous vehicles—just as sales of the combustion-engine sedans that Rebecca makes have plummeted in favor of SUVs and pickup trucks. By the end of the year, the company will have cut about 14,000 salaried and hourly workers at five factories in North America.

The reductions are one reason 48,000 U.S. employees at GM walked off the job in September, idling about 2,750 of their Canadian co-workers. The U.S. union is pushing for pay increases, less reliance on temporary workers, and faster progression of new hires to top wages. GM and the United Auto Workers reached a tentative deal on Wednesday, though the striking workers still must ratify it. The ultimate agreement will shape talks next year for GM in Canada, which has been bleeding a disproportionate number of jobs, compared with the U.S.

While GM has offered to relocate some of the Canadian workers affected by the plant closings, the shift in strategy means that after more than a century, it will stop making cars in Oshawa.

The reductions are one reason 48,000 U.S. employees at GM walked off the job in September, idling about 2,750 of their Canadian co-workers. The U.S. union is pushing for pay increases, less reliance on temporary workers, and faster progression of new hires to top wages. GM and the United Auto Workers reached a tentative deal on Wednesday, though the striking workers still must ratify it. The ultimate agreement will shape talks next year for GM in Canada, which has been bleeding a disproportionate number of jobs, compared with the U.S.

While GM has offered to relocate some of the Canadian workers affected by the plant closings, the shift in strategy means that after more than a century, it will stop making cars in Oshawa.

GM in Oshawa

PHOTOGRAPHER: LAURENCE BUTET-ROCH FOR BLOOMBERG

Rebecca, 44, sees the road crumbling behind her, with her labor union’s decline and globalization’s relentless march eroding wages and making work more precarious than ever.

“At the time when I started, it looked like there was a clear path to a pension and benefits and a reasonably good standard of living,” says Rebecca, who joined GM in 2006 as a “levelizer,” pouring transmission fluid into trucks as they rolled past her on the line, engines running. Since then, her hourly wage has dropped, even as Ontario’s minimum wage has climbed. “I see that little graph in my mind, and I’m thinking, What’s the situation going to be like in three or four years?”

Amanda Kalhous, an electrical engineer for GM, at the wheel of her GMC Terrain in Markham, Ontario, on July 26.

PHOTOGRAPHER: LAURENCE BUTET-ROCH FOR BLOOMBERG

Each workday, Amanda rises at 6:30 a.m., showers, and heads to the kitchen of her suburban, four-bedroom house, where her husband already has water boiling for her tea and lunches packed for their teenage daughters. Scooping up the breakfast and lunch she’d prepped for herself the night before, she pulls out of her two-car garage at 7 a.m., drops her youngest at the bus, and makes the 40-minute drive to Markham, Ontario, bypassing the toll road to save a bit of money on her commute to GM’s Canadian Technical Centre.

Only 50 kilometers (31 miles) west of the production line where Rebecca is putting belts on engines, the CTC could be on another planet. Inside a Silicon Valley-style incubator stocked with stand-up desks and whiteboards, Amanda’s workstation overlooks a bank of electric test vehicles parked beneath a solar-paneled car port.

Amanda Kalhous at her workstation at GM’s Canadian Technical Centre in Markham, Ontario, which overlooks a bank of electric test vehicles.

PHOTOGRAPHER: LAURENCE BUTET-ROCH FOR BLOOMBERG

A former triathlete, she recently started going back to the gym and eats her protein-rich egg bake (avocado, tomato, and ham) at her desk while juggling bureaucratic and creative tasks. On any given day, her team is testing GM algorithms for camera-based cruise control, integrating software that will keep a car in its own lane, or brainstorming features for tomorrow’s vehicles.

Wearing jeans and a gray “#InnovationLivesHere” T-shirt, Amanda talks about her work while under the eye of a GM communications rep charged with making sure no top-secret research and development information is disclosed.

Among her proudest achievements is Bluetooth technology that allows a car to communicate through a phone app without draining the car battery. The idea for Keypass—a product so cool GM made a commercialabout it—was born in 2011 out of Amanda’s annoyance that she kept forgetting her car keys but never her phone.

She and her team began experimenting with how far apart a mobile phone and car could be and still talk to each other. Bluetooth proved the most promising delivery system, but initially used too much power. She eventually came up with an app that communicates with the car to turn on the heat and lights when its owner approaches, greets the driver by name, and, most important, unlocks the door. Keypass became a feature of the Chevrolet Bolt and the first of Amanda’s patents to end up in production.

“As an engineer,” she says, “to have something that you were a part of inventing actually be in a physical vehicle—it’s huge.

Rebecca Keetch, a GM production operator, looks at the ephemera her grandfather kept from the family’s time at GM, in Oshawa, Ontario, July 2019.

PHOTOGRAPHER: LAURENCE BUTET-ROCH FOR BLOOMBERG

Amanda Kalhous and Rebecca Keetch joined General Motors Canada within a year of each other. Over the past 15 years, they’ve survived layoffs, a government bailout, and the company’s bankruptcy. Today, they’re living through something more fundamental: the biggest shift the auto industry has seen since the invention of the assembly line.

This time, only one of them has a future in it.

In any other generation, the thousands of employees being laid off by GM in Oshawa, Ontario, could easily be retrained for work elsewhere in the sector. But hard work and a solid education are no longer enough to hold onto a job in an industry that technology is upending.

GM knows what it needs to secure its future, and it’s not Rebecca, a production operator at the Oshawa factory with a community college diploma, plus 18 months of university, who places two belts on an engine every 108 seconds. It’s Amanda, an electrical engineer with two university degrees and 24 patents to her name who oversees a team that designs software for the next generation of vehicles.

Mary Barra, chief executive officer of General Motors Co., is gambling that climate change and urbanization is about to accelerate the shift to electric and autonomous vehicles—just as sales of the combustion-engine sedans that Rebecca makes have plummeted in favor of SUVs and pickup trucks. By the end of the year, the company will have cut about 14,000 salaried and hourly workers at five factories in North America.

The reductions are one reason 48,000 U.S. employees at GM walked off the job in September, idling about 2,750 of their Canadian co-workers. The U.S. union is pushing for pay increases, less reliance on temporary workers, and faster progression of new hires to top wages. GM and the United Auto Workers reached a tentative deal on Wednesday, though the striking workers still must ratify it. The ultimate agreement will shape talks next year for GM in Canada, which has been bleeding a disproportionate number of jobs, compared with the U.S.

While GM has offered to relocate some of the Canadian workers affected by the plant closings, the shift in strategy means that after more than a century, it will stop making cars in Oshawa.

The reductions are one reason 48,000 U.S. employees at GM walked off the job in September, idling about 2,750 of their Canadian co-workers. The U.S. union is pushing for pay increases, less reliance on temporary workers, and faster progression of new hires to top wages. GM and the United Auto Workers reached a tentative deal on Wednesday, though the striking workers still must ratify it. The ultimate agreement will shape talks next year for GM in Canada, which has been bleeding a disproportionate number of jobs, compared with the U.S.

While GM has offered to relocate some of the Canadian workers affected by the plant closings, the shift in strategy means that after more than a century, it will stop making cars in Oshawa.

GM in Oshawa

PHOTOGRAPHER: LAURENCE BUTET-ROCH FOR BLOOMBERG

- Read more: GM Roots Run Deep in Canada’s Fading Motor City

- Watch: A Look Back at GM’s History in Canada

Rebecca, 44, sees the road crumbling behind her, with her labor union’s decline and globalization’s relentless march eroding wages and making work more precarious than ever.

“At the time when I started, it looked like there was a clear path to a pension and benefits and a reasonably good standard of living,” says Rebecca, who joined GM in 2006 as a “levelizer,” pouring transmission fluid into trucks as they rolled past her on the line, engines running. Since then, her hourly wage has dropped, even as Ontario’s minimum wage has climbed. “I see that little graph in my mind, and I’m thinking, What’s the situation going to be like in three or four years?”

Amanda Kalhous, an electrical engineer for GM, at the wheel of her GMC Terrain in Markham, Ontario, on July 26.

PHOTOGRAPHER: LAURENCE BUTET-ROCH FOR BLOOMBERG

Each workday, Amanda rises at 6:30 a.m., showers, and heads to the kitchen of her suburban, four-bedroom house, where her husband already has water boiling for her tea and lunches packed for their teenage daughters. Scooping up the breakfast and lunch she’d prepped for herself the night before, she pulls out of her two-car garage at 7 a.m., drops her youngest at the bus, and makes the 40-minute drive to Markham, Ontario, bypassing the toll road to save a bit of money on her commute to GM’s Canadian Technical Centre.

Only 50 kilometers (31 miles) west of the production line where Rebecca is putting belts on engines, the CTC could be on another planet. Inside a Silicon Valley-style incubator stocked with stand-up desks and whiteboards, Amanda’s workstation overlooks a bank of electric test vehicles parked beneath a solar-paneled car port.

Amanda Kalhous at her workstation at GM’s Canadian Technical Centre in Markham, Ontario, which overlooks a bank of electric test vehicles.

PHOTOGRAPHER: LAURENCE BUTET-ROCH FOR BLOOMBERG

A former triathlete, she recently started going back to the gym and eats her protein-rich egg bake (avocado, tomato, and ham) at her desk while juggling bureaucratic and creative tasks. On any given day, her team is testing GM algorithms for camera-based cruise control, integrating software that will keep a car in its own lane, or brainstorming features for tomorrow’s vehicles.

Wearing jeans and a gray “#InnovationLivesHere” T-shirt, Amanda talks about her work while under the eye of a GM communications rep charged with making sure no top-secret research and development information is disclosed.

Among her proudest achievements is Bluetooth technology that allows a car to communicate through a phone app without draining the car battery. The idea for Keypass—a product so cool GM made a commercialabout it—was born in 2011 out of Amanda’s annoyance that she kept forgetting her car keys but never her phone.

She and her team began experimenting with how far apart a mobile phone and car could be and still talk to each other. Bluetooth proved the most promising delivery system, but initially used too much power. She eventually came up with an app that communicates with the car to turn on the heat and lights when its owner approaches, greets the driver by name, and, most important, unlocks the door. Keypass became a feature of the Chevrolet Bolt and the first of Amanda’s patents to end up in production.

“As an engineer,” she says, “to have something that you were a part of inventing actually be in a physical vehicle—it’s huge.

Last edited: