Rakim Allah

Superstar

Volume 10 was born Dino Hawkins in Inglewood. After spending some years living in Oakland as a kid, he returned to L.A. in the mid-1980s and attended the arts magnet middle school Hubert Howe alongside future L.A. rap luminaries Charli 2na of Jurassic 5, Son Doobie of Funkdoobiest and DJ Lethal of House of Pain. The first time Hawkins performed a rap he wrote was at the school's talent show. "The whole house fell in love with hip-hop that day," he says. "We caught the bug."

A few years later, Charli 2na introduced Hawkins, who a was going by Double D at the time, to DJ and producer Cut Chemist. The two of them recorded 10 or so songs together at Chemist's house. 2na told Volume 10 about The Good Life Cafe, a health food store in South Central that hosted a weekly event where for two hours every Thursday night, rappers could sign up to perform original songs or freestyle.

2na hadn't even gone to The Good Life yet, but Volume 10 soon checked it out. He quickly became a regular and made an impression on Freestyle Fellowship, a group of lyrically dexterous and dictionary chopping MCs who were the champions of the scene.

"It wasn't long before they put him down with the Heavyweights," says Cut Chemist, referring to the group's larger crew. "And it was tough to get respect from those guys.'"

While still in his late teens, Volume 10 was featured on "Heavyweights," the posse cut from Freestyle Fellowship's major label debut Innercity Griots. He also had an EP called Crazy As I Wanna Be that he was selling for $10 out of his pocket. "I was hot, but I didn't have a deal," he says.

Like many behind-the-scenes rap folks in the early '90s, Adrian Miller simultaneously worked in multiple parts of the industry. He had helped engineer Freestyle Fellowship's signing to Island Records, making them the first Good Life act to join a major. That experience eventually led to Miller working as an A&R at Immortal Records, the label of Buzztone Management, the company that represented Cypress Hill and House of Pain, among others (The relationship between Immortal and Buzztone was similar to that of Def Jam and Rush Artist Management; there was staff crossover, but just because an act was on one, didn't mean they were part of the other). Miller also wrote for Rap Pages magazine and helped on "Friday Night Flavas," the Power 106 radio show of the Baka Boyz, who he was managing at the time.

Immortal Records had a deal with RCA, but when the artist they had lined up to deliver an album got committed to a mental hospital, the slot opened up. Miller suggested Ras Kass, who he was close with, as a possible alternative, but then Ras Kass got in a car accident that led to a jail stint, sidelining his career for a few years.

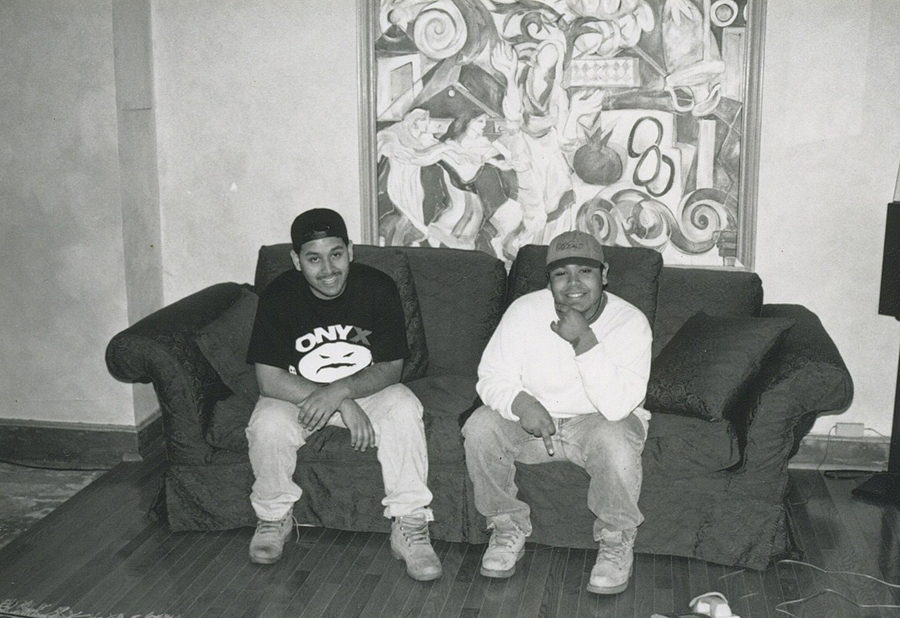

Adrian Miller and James Andrews (marketing director of Immortal Records at the time, currently of Social People) on the Baka Boyz's "Friday Nite Flavas" show. Photo courtesy of Adrian Miller

With the spot available again, Miller proposed Volume 10. Miller didn't know that at the time, Volume 10 had teamed with Ganja K, another Good Life MC, to form a group in order to get label attention. Immortal Records was open to signing the new duo, but when there were issues with Ganja K's manager, the deal went to Volume 10 as a solo act.

But problems started almost as soon as work began on the album that would become Hip-Hopera. "From day number one, Volume 10 was a self-mission," says Miller. "He wasn't interested in being a player on the team."

"I was a hard person to deal with," Volume 10 admits.

Many of the rappers from The Good Life saw themselves in the tradition of jazz artists as they stretched the possibilities of lyrical delivery and content. Though Volume 10 might have been on the forefront on the artistic and technical aspects of MCing, the songs he was interested in making weren't likely to sell many records and as recording began wrapping up on the album, it became clear to Miller that the project desperately needed something that might actually get played on the radio. Volume 10 wasn't into it.

"He fought me tooth and nail," says Miller. "I was like, Bro, I gave you a record deal. If you don't have a hit single, you ain't never going to see the light of day. Come with something."

Miller also admits that as a young and ambitious A&R, of course it was in his interest for the album to be a success. Immortal Records/Buzztone was already responsible for monster party hits like House of Pain's "Jump Around" and Funkdoobiest's "Bow Wow Wow," and his project couldn't be a dud. "I wasn't going to come with the first record that I'm executive producing and it's a wack record with no single," says Miller.

Volume 10 had been working with producers like Fat Jack and Bosco Kante. Miller set him up with the Baka Boyz, the brother duo of Nick and Eric Vidal,who weren't associated with The Good Life or the music performed there, but did have the biggest and most important hip-hop show on commercial radio in Los Angeles. The pair had been producing for acts including Yo-Yo and Kid Frost. Miller told them to make Volume 10 a beat in the style of two recent L.A. trunk thumpers, Low Profile's "Pay Your Dues" and Kam's "Peace Treaty."

A few years later, Charli 2na introduced Hawkins, who a was going by Double D at the time, to DJ and producer Cut Chemist. The two of them recorded 10 or so songs together at Chemist's house. 2na told Volume 10 about The Good Life Cafe, a health food store in South Central that hosted a weekly event where for two hours every Thursday night, rappers could sign up to perform original songs or freestyle.

2na hadn't even gone to The Good Life yet, but Volume 10 soon checked it out. He quickly became a regular and made an impression on Freestyle Fellowship, a group of lyrically dexterous and dictionary chopping MCs who were the champions of the scene.

"It wasn't long before they put him down with the Heavyweights," says Cut Chemist, referring to the group's larger crew. "And it was tough to get respect from those guys.'"

While still in his late teens, Volume 10 was featured on "Heavyweights," the posse cut from Freestyle Fellowship's major label debut Innercity Griots. He also had an EP called Crazy As I Wanna Be that he was selling for $10 out of his pocket. "I was hot, but I didn't have a deal," he says.

Like many behind-the-scenes rap folks in the early '90s, Adrian Miller simultaneously worked in multiple parts of the industry. He had helped engineer Freestyle Fellowship's signing to Island Records, making them the first Good Life act to join a major. That experience eventually led to Miller working as an A&R at Immortal Records, the label of Buzztone Management, the company that represented Cypress Hill and House of Pain, among others (The relationship between Immortal and Buzztone was similar to that of Def Jam and Rush Artist Management; there was staff crossover, but just because an act was on one, didn't mean they were part of the other). Miller also wrote for Rap Pages magazine and helped on "Friday Night Flavas," the Power 106 radio show of the Baka Boyz, who he was managing at the time.

Immortal Records had a deal with RCA, but when the artist they had lined up to deliver an album got committed to a mental hospital, the slot opened up. Miller suggested Ras Kass, who he was close with, as a possible alternative, but then Ras Kass got in a car accident that led to a jail stint, sidelining his career for a few years.

Adrian Miller and James Andrews (marketing director of Immortal Records at the time, currently of Social People) on the Baka Boyz's "Friday Nite Flavas" show. Photo courtesy of Adrian Miller

With the spot available again, Miller proposed Volume 10. Miller didn't know that at the time, Volume 10 had teamed with Ganja K, another Good Life MC, to form a group in order to get label attention. Immortal Records was open to signing the new duo, but when there were issues with Ganja K's manager, the deal went to Volume 10 as a solo act.

But problems started almost as soon as work began on the album that would become Hip-Hopera. "From day number one, Volume 10 was a self-mission," says Miller. "He wasn't interested in being a player on the team."

"I was a hard person to deal with," Volume 10 admits.

Many of the rappers from The Good Life saw themselves in the tradition of jazz artists as they stretched the possibilities of lyrical delivery and content. Though Volume 10 might have been on the forefront on the artistic and technical aspects of MCing, the songs he was interested in making weren't likely to sell many records and as recording began wrapping up on the album, it became clear to Miller that the project desperately needed something that might actually get played on the radio. Volume 10 wasn't into it.

"He fought me tooth and nail," says Miller. "I was like, Bro, I gave you a record deal. If you don't have a hit single, you ain't never going to see the light of day. Come with something."

Miller also admits that as a young and ambitious A&R, of course it was in his interest for the album to be a success. Immortal Records/Buzztone was already responsible for monster party hits like House of Pain's "Jump Around" and Funkdoobiest's "Bow Wow Wow," and his project couldn't be a dud. "I wasn't going to come with the first record that I'm executive producing and it's a wack record with no single," says Miller.

Volume 10 had been working with producers like Fat Jack and Bosco Kante. Miller set him up with the Baka Boyz, the brother duo of Nick and Eric Vidal,who weren't associated with The Good Life or the music performed there, but did have the biggest and most important hip-hop show on commercial radio in Los Angeles. The pair had been producing for acts including Yo-Yo and Kid Frost. Miller told them to make Volume 10 a beat in the style of two recent L.A. trunk thumpers, Low Profile's "Pay Your Dues" and Kam's "Peace Treaty."