ogc163

Superstar

The University of California system is getting rid of its SAT/ACT requirement. More will follow.

There’s a lot to say. First, we must distinguish between two types of tests, or really two types of testing. When people say “standardized tests,” they think of the SAT, but they also think of state-mandated exams (usually bought, at great taxpayer expense, from Pearson and other for-profit companies) that are designed to serve as assessments of public K-12 schools, of aggregates and averages of students. The SAT, ACT, GRE, GMAT, LSAT, MCAT, and similar tests are oriented towards individual ability or aptitude; they exist to show prerequisite skills to admissions officers. (And, in one of the most essential purposes of college admissions, to employers, who are restricted in the types of testing they can perform thanks to Griggs v Duke Power Co.) Sure, sometimes researchers will use SAT data to reflect on, for example, the fact that there’s no underlying educational justification for higher graduation rates1, but SATs are really about the individual. State K-12 testing is about cities and districts, and exists to provide (typically dubious) justification for changes to education policy2. SATs and similar help admissions officers sort students for spots in undergraduate and graduate programs. This post is about those predictive entrance tests like the SAT.

Share

Liberals repeat several types of myths about the SAT/ACT with such utter confidence and repetition that they’ve become a kind of holy writ. But myths they are.

There’s a lot to say. First, we must distinguish between two types of tests, or really two types of testing. When people say “standardized tests,” they think of the SAT, but they also think of state-mandated exams (usually bought, at great taxpayer expense, from Pearson and other for-profit companies) that are designed to serve as assessments of public K-12 schools, of aggregates and averages of students. The SAT, ACT, GRE, GMAT, LSAT, MCAT, and similar tests are oriented towards individual ability or aptitude; they exist to show prerequisite skills to admissions officers. (And, in one of the most essential purposes of college admissions, to employers, who are restricted in the types of testing they can perform thanks to Griggs v Duke Power Co.) Sure, sometimes researchers will use SAT data to reflect on, for example, the fact that there’s no underlying educational justification for higher graduation rates1, but SATs are really about the individual. State K-12 testing is about cities and districts, and exists to provide (typically dubious) justification for changes to education policy2. SATs and similar help admissions officers sort students for spots in undergraduate and graduate programs. This post is about those predictive entrance tests like the SAT.

Share

Liberals repeat several types of myths about the SAT/ACT with such utter confidence and repetition that they’ve become a kind of holy writ. But myths they are.

- SATs/ACTs don’t predict college success. They do, indeed. This one is clung to so desperately by liberals that you’d think there was some sort of compelling empirical basis to believe this. There isn’t. There never has been. They’re making it up. They want it to be true, and so they believe it to be true.

The predictive validity of the SAT is typically understated because the comparison we’re making has an inherent range restriction problem. If you ask “how well do the SATs predict college performance?,” you are necessarily restricting your independent variable to those who took the SAT and then went to college. But many take the SAT and do not go to college. By leaving out their data, you’re cropping the potential strength of correlation and underselling the predictive power of the SAT. When we correct statistically for this range restriction, which is not difficult, the predictive validity of the SAT and similar tests becomes remarkably strong. Range restriction is a known issue, it’s not remotely hard to understand, and your average New York Times digital subscription holder has every ability to learn about it and use that knowledge to adjust their understanding of the tests. The fact that they don’t points to the reality that liberals long ago decided that any information that does not confirm their priors can be safely discarded.

There is such a movement to deny the predictive validity of these tests that researchers at eminently-respected institutions now appear to be contriving elaborate statistical justifications for denying that validity. Last year the University of Chicago’s Elaine Allensworth and Kallie Clark published a paper, to great media fanfare, that was represented as proving that ACT scores provide no useful predictive information about college performance. But as pseudonymous researcher Dynomight shows, this result was a mirage. The paper’s authors purported to be measuring the predictive validity of the ACT and then went through a variety of dubious statistical techniques that seem to have been performed only to… reduce the demonstrated predictive validity of the ACT. As someone on Reddit put it, the paper essentially showed that if you condition for ACT scores, ACT scores aren’t predictive. Well, yeah. Conditioning on a collider is a thing. Has any publication in the mainstream press followed up critically about this much-ballyhooed study? Of course not.

Why did so many publications simply accept the Allensworth and Clark paper as given? Well, 1) most education reporters lack even basic statistical literacy and 2) the paper found the outcome that confirms the worldview of media liberals. As for the researchers themselves, I emailed them a month ago to give them a chance to defend their work; predictably, they did not respond. Does this paper constitute research fraud? No, I don’t think that would be fair. I’m sure they think the results are genuine. But aside from the jury-rigged conclusion, as is increasingly the case the paper itself simply doesn’t make the claims the press release made with anything like equal strength. Allensworth and Clark allowed the media to circulate a false claim using their statistical machinations as justification. That’s an ethical problem on its own. They will, of course, pay no professional penalty for this, as (again) the field of Education wants this result to be true.

We are, in fact, quite good at predicting which students will perform well and which won’t in later educational contexts, in all manner of contexts and with many different tools, and we have been for 100 years. I’m sorry that this is injurious to some people’s sense of how the world should be but it’s true. The SAT and ACT work to predict college performance.

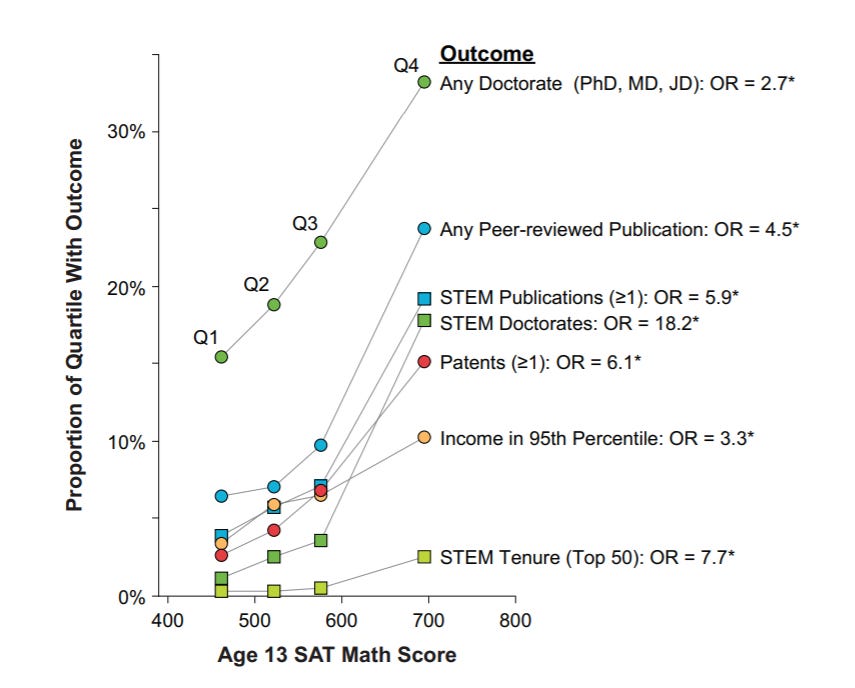

- The SATs only tell you how well a student takes the SAT. This is perhaps a corollary to 1., and is equally wrong. They tell us what they were designed to tell us: how well students are likely to perform in college. But the SATs tell us about much more than college success. Let me run this graphic again.

Robertson et al 2010

The SAT doesn’t just predict college performance, though it does that very well. It predicts all manner of major life events we associate with higher intelligence. And since the SAT and ACT are proxy IQ tests, they almost certainly provide useful information about all manner of other outcomes as well. Intelligence testing has been demonstrated to predict constructs like work performance over and over again. The SAT/ACT are predictive, and they predict differences between test takers because not all people are academically equal. Obviously.

- SATs just replicate the income distribution. No. Again, asserted with utter confidence by liberals despite overwhelming evidence that this is not true. I believe that this research represents the largest publicly-available sample of SAT scores and income information, with an n of almost 150,000, and the observed correlation between family income and SAT score is .25. This is not nothing. It is a meaningful predictor. But it means that the large majority of the variance in SAT scores is not explainable by income information. A correlation of .25 means that there are vast numbers of lower-income students outperforming higher-income students. Other analyses find similar correlations. If SAT critics wanted to say that “there is a relatively small but meaningful correlation between family income and SAT scores and we should talk about that,” fair game. But that’s not how they talk. The routinely make far stronger claims than that in an effort to dismiss these tests all together, such as here by Yale’s Paul Bloom. (Whose work I generally like.) It’s just not that hard to correlate two variables together, guys. I don’t know why you wouldn’t ever ask yourselves “is this thing I constantly assert as absolute fact actually true?” Well, maybe I do.

In general, progressive and left types routinely overstate the power of the relationship between family wealth and academic performance on all manner of educational outcomes. The political logic is obvious: if you generally want to redistribute money (as I do) then the claim that educational problems are really economic problems provides ammo for your position. But the fact that there is a generic socioeconomic effect does not mean that giving people money will improve their educational outcomes very much, particularly if richer people are actually mildly but consistently better at school than poorer for sorting reasons that are not the direct product of differences in income. That is, what correlation does exist between SES and academic indicators might simply be the metrics accurately measuring the constructs they were designed to measure.

And throwing money at our educational problems, while noble in intent, hasn’t worked. (People react violently to this, but for example poorer and Blacker public schools receive significantly higher per-pupil funding than richer and whiter schools, which should not be a surprise given that the policy apparatus has been shoveling money at the racial performance gap for 40 years.) All manner of major interventions in student socioeconomic status, including adoption into dramatically different home and family conditions, have failed to produce the benefits you’d expect if academic outcomes were a simple function of money. I believe in redistribution as a way to ameliorate the consequences of poor academic performance. There is no reason to think that redistribution will ameliorate poor academic performance itself.

- SATs are easily gamed with expensive tutoring. They are not. This one is perhaps less empirically certain than the prior two and on which I’m most amenable to counterargument, but the preponderance of the evidence seems clear to me in saying that the benefits of tutoring/coaching for these tests are vastly overstated. Again, a simplistic proffered explanation for a troublesome set of facts that then implies simplistic solutions that would not work.

- Going test optional increases racial diversity. This one, I think, must be called scientifically unsettled. However both Sweitzer, Blalock, and Sharma and Belasco, Rosinger, and Hearn find no appreciable increase in racial diversity after universities go test-optional. “Holistic” application criteria like admissions essays almost certainly benefit richer students anyway. What’s more, we have to ask ourselves what “diversity” really means in this context. Private colleges and universities keep the relevant data close to the vest, for obvious reasons, but it’s widely believed that many elite schools satisfy their internal diversity goals for Black students by aggressively pursuing wealthy Kenyan and Nigerian international students, whose parents have the means to be the kind of reliable donors that such schools rely on so heavily. I’m not aware of a really comprehensive study that examines this issue, and it would be hard to pull off, but the relevant question is “do various policies intended to improve diversity on campus actually increase the enrollment of American-born descendants of African slaves?” I can’t say, but you can guess where my suspicions lie.