The night after the Carolina Panthers lost Super Bowl 50, more than a thousand fans packed onto the sidewalks around Bank of America Stadium in Uptown Charlotte to welcome the team home. They were Black and White, poor and wealthy, successful and struggling. They stood side by side, whooping and cheering.

But at a time when Charlotte has never felt more united, the discussion in a Methodist Church some 20 miles to the South laid plain the deep divisions on race, economic opportunity, and education in a city that for decades viewed itself as a national model for successful public school integration.

The green folding chairs lined up in rows were filled, mostly, with white parents of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools students. CMS, as the district is called, serves roughly 145,000 students, is the second largest school system in North Carolina and is the 17th largest district in the nation. This meeting was in Pineville, a predominantly White small town in southern Mecklenburg County—essentially an extension of the Charlotte suburbs—that’s home to conservative politics and high-performing public schools.

The audience had gathered for a community forum about the upcoming CMS student assignment review, a process the district launches every six years or so to re-draw the boundaries that determine where kids go to school. It has almost always been acrimonious, but especially so this year. Public school campuses have resegregated by race and by income since the end of court support for the plans that integrated the districts schools. Without a judge telling CMS that the district must use student assignment to balance racial or other demographics, the school board has broad authority to draw the boundaries it sees fit.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education and groups like the one that hosted this meeting have suggested using student assignment as a tool to address economic isolation in the county’s schools. A vocal and politically influential group of parents from the suburbs disagrees, viewing the suggestion as a call to return to the court-ordered busing plan that sent children miles away from home to integrate classrooms in other parts of Charlotte.

And so—four and a half decades after the landmark Supreme Court ruling that established busing programs here and in hundreds of other school districts in the segregated South—North Carolina is once again home to a robust debate about race, poverty, and the quality of public education its students receive. It’s a discussion that’s happening elsewhere as America’s schools become increasingly segregated, but no other city has had Charlotte’s experience.

Student assignment is a contentious process. It raises concerns about the disruption of carpools and family routines. It took just under 40 minutes before a parent in the church classroom used the word fear.

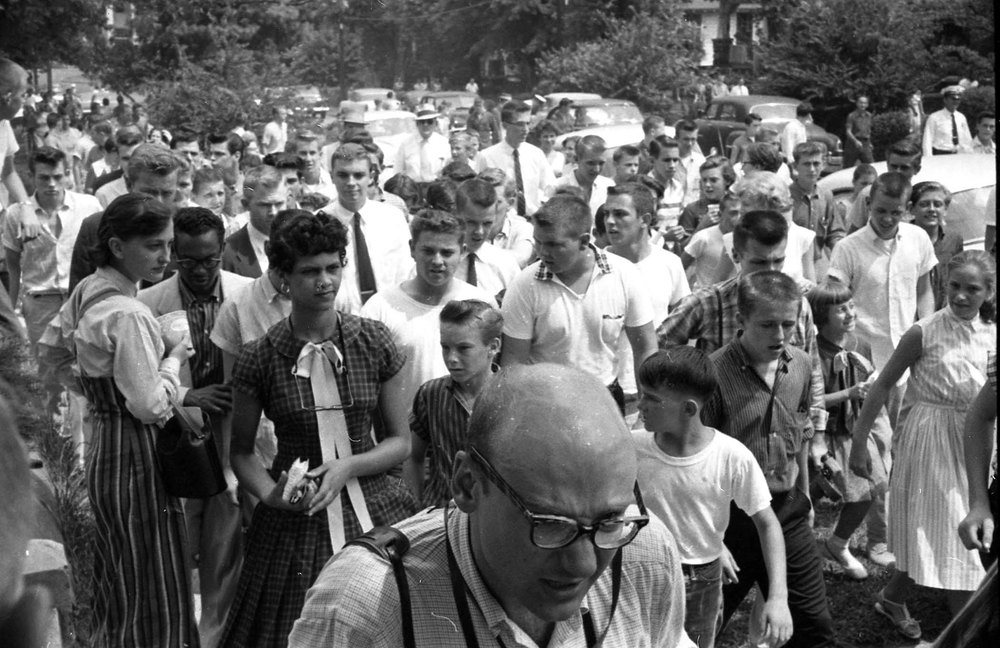

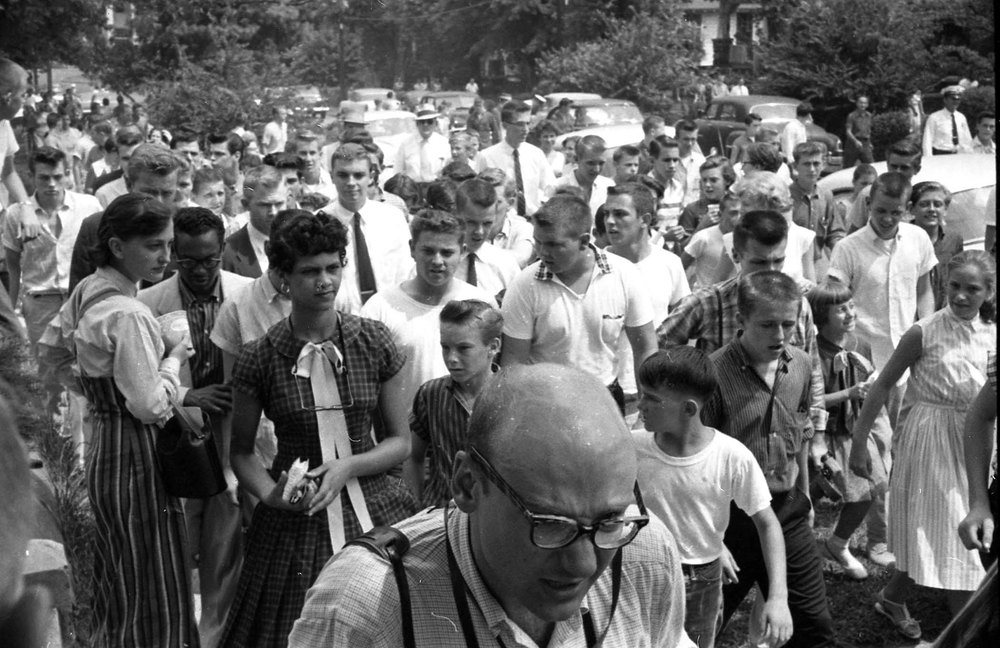

Much of the nation first learned about the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School system in September 1957, when Dorothy Counts, a Black high school student, attempted to enroll at all-White Harding High. Counts, wearing a plaid dress with a ribbon down the front, was met by an angry crowd that jeered as she walked toward the school building.

Charlotte Observer photographer Don Sturkey’s picture of the scene appeared in newspapers across the country.

Of course, his was not the first photo of Black schoolchildren braving a mob on the way to class.

Three years earlier, in 1954, a unanimous Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Educationthat state-sanctioned public school segregation, through so-called “separate but equal” policies established in 1896 under Plessy v. Ferguson, was unconstitutional.

The Brown ruling set into motion change at public schools throughout the nation—though some districts embraced desegregation more quickly than others. The Supreme Court said “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” but didn’t give guidance on how communities should go about integrating their schools. In a case the next year, the justices wrote that public school desegregation should happen “with all deliberate speed,” leaving school districts and local authority’s in charge for how and when to bring Black students into White schools.

Despite that order, Charlotte struggled with desegregation even after Dorothy Counts’s attempt to desegregate Harding. The city still had 88 segregated campuses by 1965. Many were situated close to one another in what were known as dual school zones that were de facto Black and White school districts throughout the city.

That year, when Rev. Darius Swann and his wife Vera wanted to enroll their son, James, in an integrated school, they were told to go to an all-Black school in an adjacent neighborhood. Believing the school board’s policy to be discriminatory, they filed a lawsuit through Charlotte civil rights attorney Julius Chambers that would become Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, the definitive court case on pupil assignment.

In 1969 federal judge James McMillan ordered the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board to come up with a plan to end segregated schools—a plan which McMillan rejected as insufficient. He appointed an expert from Rhode Island to devise a better, albeit complicated, strategy, which became known as the Finger Plan. It bused students of different races from neighborhood to neighborhood in an effort to fully integrate Charlotte’s schools.

In 1971, as the Finger Plan was already beginning to take hold, a unanimous Supreme Court endorsed McMillan’s ruling that busing was an acceptable strategy to use in a student assignment plan.

It’s a system that many in Charlotte believed was a success in CMS—and was a model for the nation—for nearly three decades, until the late 1990s when a suburban father sued the school district alleging his daughter was denied entrance into a CMS magnet school because she was White.

The court fight, which brought long-simmering suburban opposition to busing to the surface, once again divided Mecklenburg County. In 1999, federal judge Robert Potter—who had publicly opposed desegregation as a private citizen in the 1960s and 1970s—ruled that CMS was “unitary” and could no longer use race in student assignment decisions. The district appealed, but ultimately, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the parents.

That decision meant the school board had to adopt a new attendance boundary map—the “choice plan,” as it became known—which would move students back to the campuses closest to their homes, with options to attend magnet schools in other parts of town if parents wanted.

Fannie Flono, then a columnist for The Charlotte Observer who frequently wrote about the topics of education, race and equality, issued a grim prediction on the paper’s editorial page in the weeks after the court ruling. “Neighborhood schools,” she wrote, “will inevitably bring re-segregated schools to many sections of Charlotte. For poor black communities, that will mean concentrated poverty schools. So far, no city with such re-segregation has been able to make such schools flourish.”

Click article for more: 45 years after the Supreme Court forced its schools to integrate, Charlotte continues to debate race, poverty, and education

But at a time when Charlotte has never felt more united, the discussion in a Methodist Church some 20 miles to the South laid plain the deep divisions on race, economic opportunity, and education in a city that for decades viewed itself as a national model for successful public school integration.

The green folding chairs lined up in rows were filled, mostly, with white parents of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools students. CMS, as the district is called, serves roughly 145,000 students, is the second largest school system in North Carolina and is the 17th largest district in the nation. This meeting was in Pineville, a predominantly White small town in southern Mecklenburg County—essentially an extension of the Charlotte suburbs—that’s home to conservative politics and high-performing public schools.

The audience had gathered for a community forum about the upcoming CMS student assignment review, a process the district launches every six years or so to re-draw the boundaries that determine where kids go to school. It has almost always been acrimonious, but especially so this year. Public school campuses have resegregated by race and by income since the end of court support for the plans that integrated the districts schools. Without a judge telling CMS that the district must use student assignment to balance racial or other demographics, the school board has broad authority to draw the boundaries it sees fit.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education and groups like the one that hosted this meeting have suggested using student assignment as a tool to address economic isolation in the county’s schools. A vocal and politically influential group of parents from the suburbs disagrees, viewing the suggestion as a call to return to the court-ordered busing plan that sent children miles away from home to integrate classrooms in other parts of Charlotte.

And so—four and a half decades after the landmark Supreme Court ruling that established busing programs here and in hundreds of other school districts in the segregated South—North Carolina is once again home to a robust debate about race, poverty, and the quality of public education its students receive. It’s a discussion that’s happening elsewhere as America’s schools become increasingly segregated, but no other city has had Charlotte’s experience.

Student assignment is a contentious process. It raises concerns about the disruption of carpools and family routines. It took just under 40 minutes before a parent in the church classroom used the word fear.

Much of the nation first learned about the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School system in September 1957, when Dorothy Counts, a Black high school student, attempted to enroll at all-White Harding High. Counts, wearing a plaid dress with a ribbon down the front, was met by an angry crowd that jeered as she walked toward the school building.

Charlotte Observer photographer Don Sturkey’s picture of the scene appeared in newspapers across the country.

Of course, his was not the first photo of Black schoolchildren braving a mob on the way to class.

Three years earlier, in 1954, a unanimous Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Educationthat state-sanctioned public school segregation, through so-called “separate but equal” policies established in 1896 under Plessy v. Ferguson, was unconstitutional.

The Brown ruling set into motion change at public schools throughout the nation—though some districts embraced desegregation more quickly than others. The Supreme Court said “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” but didn’t give guidance on how communities should go about integrating their schools. In a case the next year, the justices wrote that public school desegregation should happen “with all deliberate speed,” leaving school districts and local authority’s in charge for how and when to bring Black students into White schools.

Despite that order, Charlotte struggled with desegregation even after Dorothy Counts’s attempt to desegregate Harding. The city still had 88 segregated campuses by 1965. Many were situated close to one another in what were known as dual school zones that were de facto Black and White school districts throughout the city.

That year, when Rev. Darius Swann and his wife Vera wanted to enroll their son, James, in an integrated school, they were told to go to an all-Black school in an adjacent neighborhood. Believing the school board’s policy to be discriminatory, they filed a lawsuit through Charlotte civil rights attorney Julius Chambers that would become Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, the definitive court case on pupil assignment.

In 1969 federal judge James McMillan ordered the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board to come up with a plan to end segregated schools—a plan which McMillan rejected as insufficient. He appointed an expert from Rhode Island to devise a better, albeit complicated, strategy, which became known as the Finger Plan. It bused students of different races from neighborhood to neighborhood in an effort to fully integrate Charlotte’s schools.

In 1971, as the Finger Plan was already beginning to take hold, a unanimous Supreme Court endorsed McMillan’s ruling that busing was an acceptable strategy to use in a student assignment plan.

It’s a system that many in Charlotte believed was a success in CMS—and was a model for the nation—for nearly three decades, until the late 1990s when a suburban father sued the school district alleging his daughter was denied entrance into a CMS magnet school because she was White.

The court fight, which brought long-simmering suburban opposition to busing to the surface, once again divided Mecklenburg County. In 1999, federal judge Robert Potter—who had publicly opposed desegregation as a private citizen in the 1960s and 1970s—ruled that CMS was “unitary” and could no longer use race in student assignment decisions. The district appealed, but ultimately, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the parents.

That decision meant the school board had to adopt a new attendance boundary map—the “choice plan,” as it became known—which would move students back to the campuses closest to their homes, with options to attend magnet schools in other parts of town if parents wanted.

Fannie Flono, then a columnist for The Charlotte Observer who frequently wrote about the topics of education, race and equality, issued a grim prediction on the paper’s editorial page in the weeks after the court ruling. “Neighborhood schools,” she wrote, “will inevitably bring re-segregated schools to many sections of Charlotte. For poor black communities, that will mean concentrated poverty schools. So far, no city with such re-segregation has been able to make such schools flourish.”

Click article for more: 45 years after the Supreme Court forced its schools to integrate, Charlotte continues to debate race, poverty, and education