Is She African American?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential The Official African American Thread#2

- Thread starter Rhapture

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?BoogieDown23

MY SON HAS COOKIES!

late but in

Black Lightning

Superstar

Last edited:

Black Lightning

Superstar

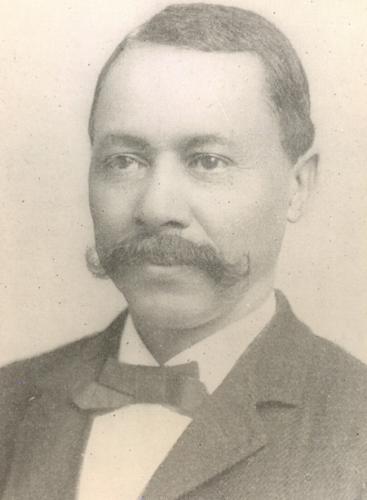

The son of a sailor, Richard Theodore Greener, a native of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania became the first African American to graduate from Harvard College. He later was assigned to serve the United States in diplomatic posts in India and Russia.

Greener lived in Boston, Massachusetts and Cambridge as a child but received his secondary education at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts and Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, He entered Harvard in 1865 and in 1870 became the first African American to receive an A.B. degree from the institution. After graduation he was appointed principal of the Male Department at Philadelphia’s Institute for Colored Youth which later became Cheyney University. Three years later Greener became professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy at the University of South Carolina where he also served as librarian and taught Greek, Mathematics and Constitutional Law. While there Greener entered the Law School and received an LL.B degree in 1876. His most prominent role as an attorney occured in 1881 when he was part of the legal team that unsuccessfrully defended West Point cadet Johnson C. Whittaker who was convicted of the charge of self-mutilation after an attack by racist fellow cadets. Whittaker had been one of Greener's students at the University of South Carolina.

Active in the Republican Party, Greener was appointed United States Consul at Bombay, India in 1898 by President William McKinley. Greener never went to India because of the Bubonic Plague then raging in Bombay. Later that year he was transferred to Vladivostok, Russia, where he served as commercial agent until 1905. During his term Greener reported to Washington on the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railroad, the rapid growth of the European Russian population in the region, the status of the local Jewish population, and the local impact of China’s Boxer Rebellion in 1900. He was decorated by the Chinese government for his role in famine relief efforts in North China in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion.

Recognizing Siberia’s growing importance to United States economic interests, Greener called unsuccessfully for the U.S. State Department to establish a consul-general in Vladivostok. During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 Greener supervised the evacuation of the Japanese from Sakhalin Island. In October, 1905 Greener was recalled from Vladivostok. He retired to Chicago, Illinois the following year and died there in 1922.

Black Lightning

Superstar

Ebenezer D. Bassett was appointed U.S. Minister Resident to Haiti in 1869, making him the first African American diplomat. For eight years, the educator, abolitionist, and black rights activist oversaw bilateral relations through bloody civil warfare and coups d'état on the island of Hispaniola. Bassett served with distinction, courage, and integrity in one of the most crucial, but difficult postings of his time.

Born in Connecticut on October 16, 1833, Ebenezer D. Bassett was the second child of Eben Tobias and Susan Gregory. In a rarity during the mid-1800s, Bassett attended college, becoming the first black student to integrate the Connecticut Normal School in 1853. He then taught in New Haven, befriending the legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Later, he became the principal of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s Institute for Colored Youth (ICY).

During the Civil War, Bassett became one of the city’s leading voices into the cause behind that conflict, the liberation of four million black slaves and helped recruit African American soldiers for the Union Army. In nominating Bassett to become Minister Resident to Haiti, President Ulysses S. Grant made him one of the highest ranking black members of the United States government.

During his tenure the American Minister Resident also dealt with cases of citizen commercial claims, diplomatic immunity for his consular and commercial agents, hurricanes, fires, and numerous tropical diseases.

The case that posed the greatest challenge to him, however, was Haitian political refugee General Pierre Boisrond Canal. The general was among the band of young leaders who had successfully ousted the former President Sylvan Salnave from power in 1869. By the time of the subsequent Michel Domingue regime in the mid 1870s Canal had retired to his home outside the capital. Domingue, the new Haitian President, however, brutally hunted down any perceived threat to his power including Canal.

General Canal came to Bassett and requested political asylum. A standoff resulted, with Bassett’s home surrounded by over a thousand of Domingue’s soldiers. Finally, after five-month siege of his residence, Bassett negotiated Canal’s safe release for exile in Jamaica.

Upon the end of the Grant Administration in 1877, Bassett submitted his resignation as was customary with a change of hands in government. When he returned to the United States, he spent an additional ten years as the Consul General for Haiti in New York City, New York. Prior to this death on November 13, 1908, he returned to live in Philadelphia, where his daughter Charlotte also taught at the ICY.

Ebenezer D. Bassett was a role model not simply for his symbolic importance as the first African American diplomat. His concern for human rights, his heroism, and courage in the face of pressure from Haitians, as well as his own capital, place him in the annals of great American diplomats.

Black Lightning

Superstar

Ambrose Caliver was born in 1894 in Saltsville, Virginia and graduated from Knoxville College in Tennessee, earning his B.A. in 1915. One year later he married Everly Rosalie Rucker. After serving as a high school teacher and a principal, he was hired in 1917 by the historically black college of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee to implement its vocational education program. Caliver rose through various positions at Fisk, finally being named dean in 1927. In the meantime, Caliver had earned his M.A. from the University of Wisconsin in 1920 and his Ph.D. from Columbia University’s Teacher’s College in 1930.

Caliver was appointed in 1930 by President Herbert Hoover to the new position of Senior Specialist in the Education of Negroes in the U.S. Office of Education. He remained in the post when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected President two years later and joined FDR’s “Black Cabinet.” In that post Caliver sought to raise national awareness about the disparities in education between blacks and whites, especially in the rural South. He traveled extensively, surveying and documenting the funding failures of public schools. During his tenure, his office published numerous articles, bulletins, and pamphlets on a variety of topics relating to African American education, from “The Education of Negro Teachers” to “Secondary Education for Negroes.” His office also created “Freedom Peoples,” a nine-part radio series broadcast on NBC that showcased African American history and achievements. Additionally, he convened conferences and implemented committees on these matters.

In 1946 Caliver was named director of the Project for Literacy Education. He measured adult illiteracy in the population, helped to create materials suitable for adult literacy education, and trained adult literacy teachers.

Though adult education had become his passion, Caliver served as an adviser for a number of national and international projects, including the U.S. Displaced Persons Commission (1949) and the United Nations Special Committee on Non-Self-Governing Territories (1950). Caliver died in 1962 in Washington, D.C. - See more at: Caliver, Ambrose (1894-1962) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed

Black Lightning

Superstar

Wendell Oliver Scott blended driving talent and determination into a long career on the otherwise all-white NASCAR Grand National tour. He is the only black to win a major-league NASCAR race. Scott was from Danville, Virginia's "Crooktown" section. His first driving job was as a taxi driver. Later he hauled illegal whiskey, an occupation that called for skills as both a high-performance mechanic and a fearless driver.

Early on, blacks were barred from many major races. In the 1920s, black drivers tried to arrange racing circuits, But the prize money was meager at best. Nevertheless, Scott set his sights on breaking into organized racing. "There were just a few blacks attending races then," Scott was quoted as saying. "Most of the time me and a friend were the only two blacks in the stands. He'd often ask me if I'd have the nerve to get out there and run. I'd tell him, 'shucks, yes,' I could do it." Scott started racing at the Danville Fairgrounds Speedway.

He won 120 races in lower divisions and in 1959, won state championships in his classes. In 1961, he was able to pull together enough money to field a car on NASCAR's top-level Grand National circuit, later renamed the Winston Cup series. Enduring persistent, sometimes brutal, discrimination, Scott raced in nearly 500 races in NASCAR's top division from 1961 through the early 1970s. Racing on a shoestring, he finished in the top ten 147 times.

On December 1, 1963, he won his only major race, a 100-mile event on a half-mile track in Jacksonville, Florida, but Scott was denied the opportunity to celebrate in Victory Circle. NASCAR officials said a scoring error was responsible for allowing another driver to accept the winner's trophy. Scott doubted that explanation. "Everybody in the place knew I had won the race," he said years later, "but the promoters and NASCAR officials didn't want me out there kissing any beauty queens or accepting any awards."

In 1973, he suffered severe injuries in a race at Talladega, Alabama. He raced only a few times afterward. Wendell Scott died in 1990.

Black Lightning

Superstar

Did African-American Slaves Rebel?

by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

One of the most pernicious allegations made against the African-American people was that our slave ancestors were either exceptionally “docile” or “content and loyal,” thus explaining their purported failure to rebel extensively. Some even compare enslaved Americans to their brothers and sisters in Brazil, Cuba, Suriname and Haiti, the last of whom defeated the most powerful army in the world, Napoleon’s army, becoming the first slaves in history to successfully strike a blow for their own freedom.

As the historian Herbert Aptheker informs us in American Negro Slave Revolts, no one put this dishonest, nakedly pro-slavery argument more baldly than the Harvard historian James Schouler in 1882, who attributed this spurious conclusion to ” ‘the innate patience, docility, and child-like simplicity of the negro’ ” who, he felt, was an ” ‘imitator and non-moralist,’ ” learning ” ‘deceit and libertinism with facility,’ ” being ” ‘easily intimidated, incapable of deep plots’ “; in short, Negroes were ” ‘a black servile race, sensuous, stupid, brutish, obedient to the whip, children in imagination.’ ”

Consider how bizarre this was: It wasn’t enough that slaves had been subjugated under a harsh and brutal regime for two and a half centuries; following the collapse of Reconstruction, this school of historians — unapologetically supportive of slavery — kicked the slaves again for not rising up more frequently to kill their oppressive masters. And lest we think that this phenomenon was relegated to 19th- and early 20th-century scholars, as late as 1959, Stanley Elkins drew a picture of the slaves as infantilized “Sambos” in his book Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life, reduced to the status of the passive, “perpetual child” by the severely oppressive form of American slavery, and thus unable to rebel. Rarely can I think of a colder, nastier set of claims than these about the lack of courage or “manhood” of the African-American slaves.

So, did African-American slaves rebel? Of course they did. As early as 1934, our old friend Joel A. Rogers identified 33 slave revolts, including Nat Turner’s, in his 100 Amazing Facts. And nine years later, the historian Herbert Aptheker published his pioneering study, American Negro Slave Revolts, to set the record straight. Aptheker defined a slave revolt as an action involving 10 or more slaves, with “freedom as the apparent aim [and] contemporary references labeling the event as an uprising, plot, insurrection, or the equivalent of these.” In all, Aptheker says, he “has found records of approximately two hundred and fifty revolts and conspiracies in the history of American Negro slavery.” Other scholars have found as many as 313.

Let’s consider the five greatest slave rebellions in the United States.

1. Stono Rebellion, 1739. The Stono Rebellion was the largest slave revolt ever staged in the 13 colonies. On Sunday, Sept. 9, 1739, a day free of labor, about 20 slaves under the leadership of a

man named Jemmy provided whites with a painful lesson on the African desire for liberty. Many members of the group were seasoned soldiers, either from the Yamasee War or from their experience in their homes in Angola, where they were captured and sold, and had been trained in the use of weapons.

They gathered at the Stono River and raided a warehouse-like store, Hutchenson’s, executing the white owners and placing their victims’ heads on the store’s front steps for all to see. They moved on to other houses in the area, killing the occupants and burning the structures, marching through the colony toward St. Augustine, Fla., where under Spanish law, they would be free.

As the march proceeded, not all slaves joined the insurrection; in fact, some hung back and actually helped hide their masters. But many were drawn to it, and the insurrectionists soon numbered about 100. They paraded down King’s Highway, according to sources, carrying banners and shouting, “Liberty!” — lukango in their native Kikongo, a word that would have expressed the English ideals embodied in liberty and, perhaps, salvation.

The slaves fought off the English for more than a week before the colonists rallied and killed most of the rebels, although some very likely reached Fort Mose. Even after Colonial forces crushed the Stono uprising, outbreaks occurred, including the very next year, when South Carolina executed at least 50 additional rebel slaves.

2. The New York City Conspiracy of 1741. With about 1,700 blacks living in a city of some 7,000 whites appearing determined to grind every person of African descent under their heel, some form of revenge seemed inevitable. In early 1741, Fort George in New York burned to the ground. Fires erupted elsewhere in the city — four in one day — and in New Jersey and on Long Island. Several white people claimed they had heard slaves bragging about setting the fires and threatening worse. They concluded that a revolt had been planned by secret black societies and gangs, inspired by a conspiracy of priests and their Catholic minions — white, black, brown, free and slave.

Certainly there were coherent ethnic groups who might have led a resistance, among them the Papa, from the Slave Coast near Whydah (Ouidah) in Benin; the Igbo, from the area around the Niger River; and the Malagasy, from Madagascar. Another identifiable and suspect group was known among the conspirators as the “Cuba People,” “negroes and mulattoes” captured in the early spring of 1740 in Cuba. They had probably been brought to New York from Havana, the greatest port of the Spanish West Indies and home to a free black population. Having been “free men in their own country,” they rightly felt unjustly enslaved in New York.

A 16-year-old Irish indentured servant, under arrest for theft, claimed knowledge of a plot by the city’s slaves — in league with a few whites — to kill white men, seize white women and incinerate the city. In the investigation that followed, 30 black men, two white men and two white women were executed. Seventy people of African descent were exiled to far-flung places like Newfoundland, Madeira, Saint-Domingue (which at independence from the French in 1804 was renamed Haiti) and Curaçao. Before the end of the summer of 1741, 17 blacks would be hanged and 13 more sent to the stake, becoming ghastly illuminations of white fears ignited by the institution of slavery they so zealously defended.

3. Gabriel’s Conspiracy, 1800. Born prophetically in 1776 on the Prosser plantation, just six miles north of Richmond, Va., and home (to use the term loosely) to 53 slaves, a slave named Gabriel would hatch a plot, with freedom as its goal, that was emblematic of the era in which he lived.

A skilled blacksmith who stood more than six feet tall and dressed in fine clothes when he was away from the forge, Gabriel cut an imposing figure. But what distinguished him more than his physical bearing was his ability to read and write: Only 5 percent of Southern slaves were literate.

Other slaves looked up to men like Gabriel, and Gabriel himself found inspiration in the French and Saint-Domingue revolutions of 1789. He imbibed the political fervor of the era and concluded, albeit erroneously, that Jeffersonian democratic ideology encompassed the interests of black slaves and white workingmen alike, who, united, could oppose the oppressive Federalist merchant class.

Spurred on by two liberty-minded French soldiers he met in a tavern, Gabriel began to formulate a plan, enlisting his brother Solomon and another servant on the Prosser plantation in his fight for freedom. Word quickly spread to Richmond, other nearby towns and plantations and well beyond to Petersburg and Norfolk, via free and enslaved blacks who worked the waterways. Gabriel took a tremendous risk in letting so many black people learn of his plans: It was necessary as a means of attracting supporters, but it also exposed him to the possibility of betrayal.

Regardless, Gabriel persevered, aiming to rally at least 1,000 slaves to his banner of “Death or Liberty,” an inversion of the famed cry of the slaveholding revolutionary Patrick Henry. With incredible daring — and naïveté — Gabriel determined to march to Richmond, take the armory and hold Gov. James Monroe hostage until the merchant class bent to the rebels’ demands of equal rights for all. He planned his uprising for August 30 and publicized it well.

But on that day, one of the worst thunderstorms in recent memory pummeled Virginia, washing away roads and making travel all but impossible. Undeterred, Gabriel believed that only a small band was necessary to carry out the plan. But many of his followers lost faith, and he was betrayed by a slave named Pharoah, who feared retribution if the plot failed.

The rebellion was barely under way when the state captured Gabriel and several co-conspirators. Twenty-five African Americans, worth about $9,000 or so — money that cash-strapped Virginia surely thought it could ill afford — were hanged together before Gabriel went to the gallows and was executed, alone.

4. German Coast Uprising, 1811. If the Haitian Revolution between 1791 and 1804 — spearheaded by Touissant Louverture and fought and won by black slaves under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines — struck fear in the hearts of slave owners everywhere, it struck a loud and electrifying chord with African slaves in America.

In 1811, about 40 miles north of New Orleans, Charles Deslondes, a mulatto slave driver on the Andry sugar plantation in the German Coast area of Louisiana, took volatile inspiration from that victory seven years prior in Haiti. He would go on to lead what the young historian Daniel Rasmussen calls the largest and most sophisticated slave revolt in U.S. history in his book American Uprising. (The Stono Rebellion had been the largest slave revolt on these shores to this point, but that occurred in the colonies, before America won its independence from Great Britain.) After communicating his intentions to slaves on the Andry plantation and in nearby areas, on the rainy evening of Jan. 8, Deslondes and about 25 slaves rose up and attacked the plantation’s owner and family. They hacked to death one of the owner’s sons, but carelessly allowed the master to escape.

That was a tactical mistake to be sure, but Deslondes and his men had wisely chosen the well-outfitted Andry plantation — a warehouse for the local militia — as the place to begin their revolt. They ransacked the stores and seized uniforms, guns and ammunition. As they moved toward New Orleans, intending to capture the city, dozens more men and women joined the cause, singing Creole protest songs while pillaging plantations and murdering whites. Some estimated that the force ultimately swelled to 300, but it’s unlikely that Deslondes’ army exceeded 124.

The South Carolina congressman, slave master and Indian fighter Wade Hampton was assigned the task of suppressing the insurrection. With a combined force of about 30 regular U.S. Army soldiers and militia, it would take Hampton two days to stop the rebels. They fought a pitched battle that ended only when the slaves ran out of ammunition, about 20 miles from New Orleans. In the slaughter that followed, the slaves’ lack of military experience was evident: The whites suffered no casualties, but when the slaves surrendered, about 20 insurgents lay dead, another 50 became prisoners and the remainder fled into the swamps.

By the end of the month, whites had rounded up another 50 insurgents. In short order, about 100 survivors were summarily executed, their heads severed and placed along the road to New Orleans. As one planter noted, they looked “like crows sitting on long poles.”

5. Nat Turner’s Rebellion, 1831. Born on Oct. 2, 1800, in Southampton County, Va., the week before Gabriel was hanged, Nat Turner impressed family and friends with an unusual sense of purpose, even as a child. Driven by prophetic visions and joined by a host of followers — but with no clear goals — on August 22, 1831, Turner and about 70 armed slaves and free blacks set off to slaughter the white neighbors who enslaved them.

In the early hours of the morning, they bludgeoned Turner’s master and his master’s wife and children with axes. By the end of the next day, the rebels had attacked about 15 homes and killed between 55 and 60 whites as they moved toward the religiously named county seat of Jerusalem, Va. Other slaves who had planned to join the rebellion suddenly turned against it after white militia began to attack Turner’s men, undoubtedly concluding that he was bound to fail. Most of the rebels were captured quickly, but Turner eluded authorities for more than a month.

On Sunday, Oct. 30, a local white man stumbled upon Turner’s hideout and seized him. A special Virginia court tried him on Nov. 5 and sentenced him to hang six days later. A barbaric scene followed his execution. Enraged whites took his body, skinned it, distributed parts as souvenirs and rendered his remains into grease. His head was removed and for a time sat in the biology department of Wooster College in Ohio. (In fact, it is likely that pieces of his body — including his skull and a purse made from his skin — have been preserved and are hidden in storage somewhere.)

Of his fellow rebels, 21 went to the gallows, and another 16 were sold away from the region. As the state reacted with harsher laws controlling black people, many free blacks fled Virginia for good. Turner remains a legendary figure, remembered for the bloody path he forged in his personal war against slavery, and for the grisly and garish way he was treated in death.

The heroism and sacrifices of these slave insurrectionists would be a prelude to the noble performance of some 200,000 black men who served so very courageously in the Civil War, the war that finally put an end to the evil institution that in 1860 chained some 3.9 million human beings to perpetual bondage.

by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

One of the most pernicious allegations made against the African-American people was that our slave ancestors were either exceptionally “docile” or “content and loyal,” thus explaining their purported failure to rebel extensively. Some even compare enslaved Americans to their brothers and sisters in Brazil, Cuba, Suriname and Haiti, the last of whom defeated the most powerful army in the world, Napoleon’s army, becoming the first slaves in history to successfully strike a blow for their own freedom.

As the historian Herbert Aptheker informs us in American Negro Slave Revolts, no one put this dishonest, nakedly pro-slavery argument more baldly than the Harvard historian James Schouler in 1882, who attributed this spurious conclusion to ” ‘the innate patience, docility, and child-like simplicity of the negro’ ” who, he felt, was an ” ‘imitator and non-moralist,’ ” learning ” ‘deceit and libertinism with facility,’ ” being ” ‘easily intimidated, incapable of deep plots’ “; in short, Negroes were ” ‘a black servile race, sensuous, stupid, brutish, obedient to the whip, children in imagination.’ ”

Consider how bizarre this was: It wasn’t enough that slaves had been subjugated under a harsh and brutal regime for two and a half centuries; following the collapse of Reconstruction, this school of historians — unapologetically supportive of slavery — kicked the slaves again for not rising up more frequently to kill their oppressive masters. And lest we think that this phenomenon was relegated to 19th- and early 20th-century scholars, as late as 1959, Stanley Elkins drew a picture of the slaves as infantilized “Sambos” in his book Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life, reduced to the status of the passive, “perpetual child” by the severely oppressive form of American slavery, and thus unable to rebel. Rarely can I think of a colder, nastier set of claims than these about the lack of courage or “manhood” of the African-American slaves.

So, did African-American slaves rebel? Of course they did. As early as 1934, our old friend Joel A. Rogers identified 33 slave revolts, including Nat Turner’s, in his 100 Amazing Facts. And nine years later, the historian Herbert Aptheker published his pioneering study, American Negro Slave Revolts, to set the record straight. Aptheker defined a slave revolt as an action involving 10 or more slaves, with “freedom as the apparent aim [and] contemporary references labeling the event as an uprising, plot, insurrection, or the equivalent of these.” In all, Aptheker says, he “has found records of approximately two hundred and fifty revolts and conspiracies in the history of American Negro slavery.” Other scholars have found as many as 313.

Let’s consider the five greatest slave rebellions in the United States.

1. Stono Rebellion, 1739. The Stono Rebellion was the largest slave revolt ever staged in the 13 colonies. On Sunday, Sept. 9, 1739, a day free of labor, about 20 slaves under the leadership of a

man named Jemmy provided whites with a painful lesson on the African desire for liberty. Many members of the group were seasoned soldiers, either from the Yamasee War or from their experience in their homes in Angola, where they were captured and sold, and had been trained in the use of weapons.

They gathered at the Stono River and raided a warehouse-like store, Hutchenson’s, executing the white owners and placing their victims’ heads on the store’s front steps for all to see. They moved on to other houses in the area, killing the occupants and burning the structures, marching through the colony toward St. Augustine, Fla., where under Spanish law, they would be free.

As the march proceeded, not all slaves joined the insurrection; in fact, some hung back and actually helped hide their masters. But many were drawn to it, and the insurrectionists soon numbered about 100. They paraded down King’s Highway, according to sources, carrying banners and shouting, “Liberty!” — lukango in their native Kikongo, a word that would have expressed the English ideals embodied in liberty and, perhaps, salvation.

The slaves fought off the English for more than a week before the colonists rallied and killed most of the rebels, although some very likely reached Fort Mose. Even after Colonial forces crushed the Stono uprising, outbreaks occurred, including the very next year, when South Carolina executed at least 50 additional rebel slaves.

2. The New York City Conspiracy of 1741. With about 1,700 blacks living in a city of some 7,000 whites appearing determined to grind every person of African descent under their heel, some form of revenge seemed inevitable. In early 1741, Fort George in New York burned to the ground. Fires erupted elsewhere in the city — four in one day — and in New Jersey and on Long Island. Several white people claimed they had heard slaves bragging about setting the fires and threatening worse. They concluded that a revolt had been planned by secret black societies and gangs, inspired by a conspiracy of priests and their Catholic minions — white, black, brown, free and slave.

Certainly there were coherent ethnic groups who might have led a resistance, among them the Papa, from the Slave Coast near Whydah (Ouidah) in Benin; the Igbo, from the area around the Niger River; and the Malagasy, from Madagascar. Another identifiable and suspect group was known among the conspirators as the “Cuba People,” “negroes and mulattoes” captured in the early spring of 1740 in Cuba. They had probably been brought to New York from Havana, the greatest port of the Spanish West Indies and home to a free black population. Having been “free men in their own country,” they rightly felt unjustly enslaved in New York.

A 16-year-old Irish indentured servant, under arrest for theft, claimed knowledge of a plot by the city’s slaves — in league with a few whites — to kill white men, seize white women and incinerate the city. In the investigation that followed, 30 black men, two white men and two white women were executed. Seventy people of African descent were exiled to far-flung places like Newfoundland, Madeira, Saint-Domingue (which at independence from the French in 1804 was renamed Haiti) and Curaçao. Before the end of the summer of 1741, 17 blacks would be hanged and 13 more sent to the stake, becoming ghastly illuminations of white fears ignited by the institution of slavery they so zealously defended.

3. Gabriel’s Conspiracy, 1800. Born prophetically in 1776 on the Prosser plantation, just six miles north of Richmond, Va., and home (to use the term loosely) to 53 slaves, a slave named Gabriel would hatch a plot, with freedom as its goal, that was emblematic of the era in which he lived.

A skilled blacksmith who stood more than six feet tall and dressed in fine clothes when he was away from the forge, Gabriel cut an imposing figure. But what distinguished him more than his physical bearing was his ability to read and write: Only 5 percent of Southern slaves were literate.

Other slaves looked up to men like Gabriel, and Gabriel himself found inspiration in the French and Saint-Domingue revolutions of 1789. He imbibed the political fervor of the era and concluded, albeit erroneously, that Jeffersonian democratic ideology encompassed the interests of black slaves and white workingmen alike, who, united, could oppose the oppressive Federalist merchant class.

Spurred on by two liberty-minded French soldiers he met in a tavern, Gabriel began to formulate a plan, enlisting his brother Solomon and another servant on the Prosser plantation in his fight for freedom. Word quickly spread to Richmond, other nearby towns and plantations and well beyond to Petersburg and Norfolk, via free and enslaved blacks who worked the waterways. Gabriel took a tremendous risk in letting so many black people learn of his plans: It was necessary as a means of attracting supporters, but it also exposed him to the possibility of betrayal.

Regardless, Gabriel persevered, aiming to rally at least 1,000 slaves to his banner of “Death or Liberty,” an inversion of the famed cry of the slaveholding revolutionary Patrick Henry. With incredible daring — and naïveté — Gabriel determined to march to Richmond, take the armory and hold Gov. James Monroe hostage until the merchant class bent to the rebels’ demands of equal rights for all. He planned his uprising for August 30 and publicized it well.

But on that day, one of the worst thunderstorms in recent memory pummeled Virginia, washing away roads and making travel all but impossible. Undeterred, Gabriel believed that only a small band was necessary to carry out the plan. But many of his followers lost faith, and he was betrayed by a slave named Pharoah, who feared retribution if the plot failed.

The rebellion was barely under way when the state captured Gabriel and several co-conspirators. Twenty-five African Americans, worth about $9,000 or so — money that cash-strapped Virginia surely thought it could ill afford — were hanged together before Gabriel went to the gallows and was executed, alone.

4. German Coast Uprising, 1811. If the Haitian Revolution between 1791 and 1804 — spearheaded by Touissant Louverture and fought and won by black slaves under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines — struck fear in the hearts of slave owners everywhere, it struck a loud and electrifying chord with African slaves in America.

In 1811, about 40 miles north of New Orleans, Charles Deslondes, a mulatto slave driver on the Andry sugar plantation in the German Coast area of Louisiana, took volatile inspiration from that victory seven years prior in Haiti. He would go on to lead what the young historian Daniel Rasmussen calls the largest and most sophisticated slave revolt in U.S. history in his book American Uprising. (The Stono Rebellion had been the largest slave revolt on these shores to this point, but that occurred in the colonies, before America won its independence from Great Britain.) After communicating his intentions to slaves on the Andry plantation and in nearby areas, on the rainy evening of Jan. 8, Deslondes and about 25 slaves rose up and attacked the plantation’s owner and family. They hacked to death one of the owner’s sons, but carelessly allowed the master to escape.

That was a tactical mistake to be sure, but Deslondes and his men had wisely chosen the well-outfitted Andry plantation — a warehouse for the local militia — as the place to begin their revolt. They ransacked the stores and seized uniforms, guns and ammunition. As they moved toward New Orleans, intending to capture the city, dozens more men and women joined the cause, singing Creole protest songs while pillaging plantations and murdering whites. Some estimated that the force ultimately swelled to 300, but it’s unlikely that Deslondes’ army exceeded 124.

The South Carolina congressman, slave master and Indian fighter Wade Hampton was assigned the task of suppressing the insurrection. With a combined force of about 30 regular U.S. Army soldiers and militia, it would take Hampton two days to stop the rebels. They fought a pitched battle that ended only when the slaves ran out of ammunition, about 20 miles from New Orleans. In the slaughter that followed, the slaves’ lack of military experience was evident: The whites suffered no casualties, but when the slaves surrendered, about 20 insurgents lay dead, another 50 became prisoners and the remainder fled into the swamps.

By the end of the month, whites had rounded up another 50 insurgents. In short order, about 100 survivors were summarily executed, their heads severed and placed along the road to New Orleans. As one planter noted, they looked “like crows sitting on long poles.”

5. Nat Turner’s Rebellion, 1831. Born on Oct. 2, 1800, in Southampton County, Va., the week before Gabriel was hanged, Nat Turner impressed family and friends with an unusual sense of purpose, even as a child. Driven by prophetic visions and joined by a host of followers — but with no clear goals — on August 22, 1831, Turner and about 70 armed slaves and free blacks set off to slaughter the white neighbors who enslaved them.

In the early hours of the morning, they bludgeoned Turner’s master and his master’s wife and children with axes. By the end of the next day, the rebels had attacked about 15 homes and killed between 55 and 60 whites as they moved toward the religiously named county seat of Jerusalem, Va. Other slaves who had planned to join the rebellion suddenly turned against it after white militia began to attack Turner’s men, undoubtedly concluding that he was bound to fail. Most of the rebels were captured quickly, but Turner eluded authorities for more than a month.

On Sunday, Oct. 30, a local white man stumbled upon Turner’s hideout and seized him. A special Virginia court tried him on Nov. 5 and sentenced him to hang six days later. A barbaric scene followed his execution. Enraged whites took his body, skinned it, distributed parts as souvenirs and rendered his remains into grease. His head was removed and for a time sat in the biology department of Wooster College in Ohio. (In fact, it is likely that pieces of his body — including his skull and a purse made from his skin — have been preserved and are hidden in storage somewhere.)

Of his fellow rebels, 21 went to the gallows, and another 16 were sold away from the region. As the state reacted with harsher laws controlling black people, many free blacks fled Virginia for good. Turner remains a legendary figure, remembered for the bloody path he forged in his personal war against slavery, and for the grisly and garish way he was treated in death.

The heroism and sacrifices of these slave insurrectionists would be a prelude to the noble performance of some 200,000 black men who served so very courageously in the Civil War, the war that finally put an end to the evil institution that in 1860 chained some 3.9 million human beings to perpetual bondage.

Black Lightning

Superstar

“Ms. Esther Jones, known by her stage name, "Baby Esther,” was an African-American singer and entertainer of the late 1920s. She performed regularly at The Cotton Club in Harlem. Her singing trademark was…“boop oop a doop, "in a babyish voice. Singer Helen Kane purportedly saw Baby’s act in 1928 and "adopted” her style in her hit song “I Wanna Be Loved By You.” Ms. Jones’ singing style, along with Ms. Kane’s hit song, went on to become the inspiration for Max Fleischer’s ‘BETTY BOOP.’“

Woah! I never knew this.......white folk wouldn't even let us have our own cartoons smh. If she has any surviving family members, they should sue for some royalty checks!

“Ms. Esther Jones, known by her stage name, "Baby Esther,” was an African-American singer and entertainer of the late 1920s. She performed regularly at The Cotton Club in Harlem. Her singing trademark was…“boop oop a doop, "in a babyish voice. Singer Helen Kane purportedly saw Baby’s act in 1928 and "adopted” her style in her hit song “I Wanna Be Loved By You.” Ms. Jones’ singing style, along with Ms. Kane’s hit song, went on to become the inspiration for Max Fleischer’s ‘BETTY BOOP.’“

B-BOYING?!

The expression B-Boying probably originated from the african word "Boioing" which means to "hop, jump" and which was used in the Bronx River area (NYC) to describe the bouncy style of Breaking that the B-Boys did.

It was also used to describe the ball on their ski hats that went boioing when they danced.

The "B" of B-Girl/B-Boy stands for Break-Girl/Break-Boy (some use it also for Boogie or Bronx) because they got down to the floor during compounded and therefore expanded breaksections of records: Break on the Breaks.

B-Boying - also known as Breaking or "Breakdance" (the latter term was created by the media) - should not be mixed up with Popping (Electric Boogaloo) and Locking because these dancestyles have their own terms, histories and pioneers.

THE ROOTS

Breaking, also known as Rocking at first, was a reflection of African American as well as Latino (Puerto Rican) culture brought by the immigrants and emerged in New York City in the late 60ies and beginning of the 70ies.

Break was also the section on a musical recording where the percussive rhythms were most aggressive and hard driving. The dancers anticipated and reacted to these breaks with their most impressive steps and moves. Kool DJ Herc is credited with extending these breaks by using two turntables and going back-n-forth with two copies of the same song that the dancers were able to enjoy more than just a few seconds of a break.

In the early stages this dance was done upright, a form which became known as "top rocking". The structure and form of toprocking has influences from Brooklyn uprocking, tap dance, lindy hop aka jitterbug, salsa (like the latin rock), Afro Cuban and various African and Native American (like the indian step) dances. There is also a toprock Charleston step called the "Charlie Rock". Another major influence and inspiration was James Brown with his hits "Popcorn" (1969) and "Get on the Good Foot" (1972): Inspired by his energetic and almost acrobatic dance on stage, people started to dance the "Good Foot".

As the tradition of dance battle was already well established at that time and as Rocking/Breaking also got incorporated into the Hip Hop culture ("fight with creativity not with weapons"), it became more and more a dance that involved the dancer using their imagination to execute foot stomps, shuffles, punches and other battle movements. As a result it wasn't long before top rockers extended their repetoire to the ground with "footwork" ("floor rocking") and "freezes".

Floor rocking, influenced by material arts films from the early 70ies, tap dance (russian style footwork, swipes, sweeps, one shot headspins from a cart wheel, ..) and other dance forms, didn't replace toprocking but it was added to and became another key point in the dance. The transition from the top to the ground was called the "godown" or the "drop" (like front swipes, back swipes, dips and corkscrews). The smoother the drop, the better.

Freezes were usually used to end a series of combinations or to mock and humilitate the opponent. Certain freezes were also named like the two most popular: "chair freeze" and "baby freeze". The chair freeze became the foundation for various moves because of the potential range of motion a dancer had in this position (hand, forearm and elbow support the body while allowing free range of movement with the legs and hips).

The main goal in a Breaking Battle was to beat the "opponent" by being more creative with Steps and Freezes and by doing better and faster Moves. That's also why Breaking crews - groups of dancers who practiced and performed together - were formed for developing their own dance routines to stand out against other crews.

The first known Breaking Crew was called The nikka Twins and with other crews like The Zulu Kings, The Seven Deadly Sinners, Shanghai Brothers, The Bronx Boys, Rockwell Association, Starchild La Rock, Rock Steady Crew and the Crazy Commanders (where the name for the CC step is coming from) they were the pioneers. After some years of developing this new dance style there were dancers around in the middle of the 70's who had already remarkable skills. The following dancers were the B-Boy Kings in the mid 70's: Beaver, Robbie Rob (Zulu Kings), Vinnie, Off (Salsoul), Bos (Starchild La Rock), Willie Wil, Lil' Carlos (Rockwell Association), Spy, Shorty (Crazy Commanders), James Bond, Larry Lar, Charlie Rock (KC Crew), Spidey, Walter (Master Plan) and others...

The biggest crew rivalries during that period (which was the driving force and which was what kept the crews alive) were between SalSoul (this crew changed their name later on to The DiscoKids) and Zulu Kings as well as between Starchild La Rock and Rockwell Association. At that time Breakin was still just about Freezes, Footworks and Toprocks. There were no Spins! By the late 70's a lot of early B-Boys retired and a new generation of dancers grew up who combined the till then known basics with more and more spins on almost every part of the body. Nowadays well known moves like Headspin, Continues Backspin (aka Windmill) and all kind of glides were created at that time.

Around the 80's there were crews in NYC like Rock Steady Crew, NYC Breakers, Dynamic Rockers, United States Breakers, Crazy Breakers, Floor Lords, Floor Masters, Incredible Breakers, Magnificient Force and much more. Some of the best dancers at that time were guys like Chino, Brian, German (Incredible Breakers), Dr. Love (Master Mind), Flip (Scrambling Feet), Tiny (Incredible Body Mechanic) and many more. The biggest rivalries during that time were between Rock Steady Crew and NYC Breakers as well as between Rock Steady Crew and Dynamic Rockers. The early 80's battles between these crews attracted the attention of the media.

In '81 the ABC News showed a performance of Rock Steady Crew at Lincoln Center. Then in '82 a battle between Rock Steady Crew and Dynamic Rockers was recorded for the film/documentary "Style Wars" which was later on also aired nationally on PBS and that's how Breakin found the way to the West Coast of the USA. In the same year the "Roxy" formerly known as a Rollerskate Disco was reopened as a Hip Hop Club.

In '83 the movie "Flashdance" came into the cinemas and the video clip of Malcolm McLarens "Buffalo Gals" was showed on TV. Rock Steady Crew was featured in both productions and they were seen all over the world because of the success of this movie and this song. That was the release for the media explosion in most of the countries all around the world. For everybody Breakin was something new, something that has never been seen before, something that was really spectacular and fascinating. Still in the same year the movie "Wild Style" came out and to promote it the "Wild Style" - tour took place, which was the first international tour featuring Hip Hop culture. The MCs, DJs, Graffiti artists and Breakers went also to London and Paris and this was the first time that Breaking could be seen "live" in Europe.

In '84 the movie "Beat Street" came out which featured Rock Steady Crew, NYC Breakers and Magnificent Force and at the closing ceremonies of the LA Olympic Summer Games over 100 B-Boys and B-Girls did a performance! Still in the same year the "Swatch Watch NYC Fresh Tour" took place and the movie "Breakin" was shot and a year later in '85 also "Breakin 2: Electric Boogaloo". Both were filmed at the nightclub called "Radio" (later "Radiotron") in LA and they showed what was going on at the WestCoast of the USA.

Breakin became more and more a trend and B-Boys appeared in commercials (for milk, Right Guard, Burger King,..) and TV shows (Fame, That's Incredible!, David Letterman,..). B-Boys were even honoured guests of the prince of Bahrain and of Queen Elizabeth. '85 was also the release of "Electro Rock" - a video which was filmed at a party in the "Hippodome" in London and which showed the UK Hip Hop Scene (with guests from the USA). In '86 the UK FRESH took place in the Wembley Arena (London) which was one of the biggest and most historical events at that time.

In '87 for most people and particularly for the media "Breakdance" was played out. Only very few dancers kept on practicing and dancing seriously, not only in New York but all around the world.

More history coming soon...

(Resources: Word of mouth, interviews and articles of Fabel & Mr Wiggles)

RELATED DANCES

Breaking was and is influenced by many other dancestyles, by gymnastics and even also very strongly by eastern material art moves.

Despite of many rumours and opinions Breaking didn't originate from Capoeira but during the last few years many moves, steps and freezes of this Brazilian (fight-) dance have inspired more and more B-Girls and B-Boys who integrated them into their dance. [read more]

A special dancestyle which is very often used by B-Boys (during their toprock or/and for battling) and which originated in Brooklyn (NYC) is Uprocking. [read more]

In the early/mid 80ies "Breakdance" was often mixed and presented by the media together with Boogaloo, Popping, Robotting, Strutting, Waving and other funk dance styles. Although these dance styles were more and more adopted into the hip-hop movement, they were created in the West Coast during the Funk Era and its roots and history are fundamentally different from B-Boying.

History of Popping and Boogaloo

History of (Campbel-)Locking

© copyright 1986-2010 Spartanic Rockers. All Rights Reserved.

The Roots

The expression B-Boying probably originated from the african word "Boioing" which means to "hop, jump" and which was used in the Bronx River area (NYC) to describe the bouncy style of Breaking that the B-Boys did.

It was also used to describe the ball on their ski hats that went boioing when they danced.

The "B" of B-Girl/B-Boy stands for Break-Girl/Break-Boy (some use it also for Boogie or Bronx) because they got down to the floor during compounded and therefore expanded breaksections of records: Break on the Breaks.

B-Boying - also known as Breaking or "Breakdance" (the latter term was created by the media) - should not be mixed up with Popping (Electric Boogaloo) and Locking because these dancestyles have their own terms, histories and pioneers.

THE ROOTS

Breaking, also known as Rocking at first, was a reflection of African American as well as Latino (Puerto Rican) culture brought by the immigrants and emerged in New York City in the late 60ies and beginning of the 70ies.

Break was also the section on a musical recording where the percussive rhythms were most aggressive and hard driving. The dancers anticipated and reacted to these breaks with their most impressive steps and moves. Kool DJ Herc is credited with extending these breaks by using two turntables and going back-n-forth with two copies of the same song that the dancers were able to enjoy more than just a few seconds of a break.

In the early stages this dance was done upright, a form which became known as "top rocking". The structure and form of toprocking has influences from Brooklyn uprocking, tap dance, lindy hop aka jitterbug, salsa (like the latin rock), Afro Cuban and various African and Native American (like the indian step) dances. There is also a toprock Charleston step called the "Charlie Rock". Another major influence and inspiration was James Brown with his hits "Popcorn" (1969) and "Get on the Good Foot" (1972): Inspired by his energetic and almost acrobatic dance on stage, people started to dance the "Good Foot".

As the tradition of dance battle was already well established at that time and as Rocking/Breaking also got incorporated into the Hip Hop culture ("fight with creativity not with weapons"), it became more and more a dance that involved the dancer using their imagination to execute foot stomps, shuffles, punches and other battle movements. As a result it wasn't long before top rockers extended their repetoire to the ground with "footwork" ("floor rocking") and "freezes".

Floor rocking, influenced by material arts films from the early 70ies, tap dance (russian style footwork, swipes, sweeps, one shot headspins from a cart wheel, ..) and other dance forms, didn't replace toprocking but it was added to and became another key point in the dance. The transition from the top to the ground was called the "godown" or the "drop" (like front swipes, back swipes, dips and corkscrews). The smoother the drop, the better.

Freezes were usually used to end a series of combinations or to mock and humilitate the opponent. Certain freezes were also named like the two most popular: "chair freeze" and "baby freeze". The chair freeze became the foundation for various moves because of the potential range of motion a dancer had in this position (hand, forearm and elbow support the body while allowing free range of movement with the legs and hips).

The main goal in a Breaking Battle was to beat the "opponent" by being more creative with Steps and Freezes and by doing better and faster Moves. That's also why Breaking crews - groups of dancers who practiced and performed together - were formed for developing their own dance routines to stand out against other crews.

The first known Breaking Crew was called The nikka Twins and with other crews like The Zulu Kings, The Seven Deadly Sinners, Shanghai Brothers, The Bronx Boys, Rockwell Association, Starchild La Rock, Rock Steady Crew and the Crazy Commanders (where the name for the CC step is coming from) they were the pioneers. After some years of developing this new dance style there were dancers around in the middle of the 70's who had already remarkable skills. The following dancers were the B-Boy Kings in the mid 70's: Beaver, Robbie Rob (Zulu Kings), Vinnie, Off (Salsoul), Bos (Starchild La Rock), Willie Wil, Lil' Carlos (Rockwell Association), Spy, Shorty (Crazy Commanders), James Bond, Larry Lar, Charlie Rock (KC Crew), Spidey, Walter (Master Plan) and others...

The biggest crew rivalries during that period (which was the driving force and which was what kept the crews alive) were between SalSoul (this crew changed their name later on to The DiscoKids) and Zulu Kings as well as between Starchild La Rock and Rockwell Association. At that time Breakin was still just about Freezes, Footworks and Toprocks. There were no Spins! By the late 70's a lot of early B-Boys retired and a new generation of dancers grew up who combined the till then known basics with more and more spins on almost every part of the body. Nowadays well known moves like Headspin, Continues Backspin (aka Windmill) and all kind of glides were created at that time.

Around the 80's there were crews in NYC like Rock Steady Crew, NYC Breakers, Dynamic Rockers, United States Breakers, Crazy Breakers, Floor Lords, Floor Masters, Incredible Breakers, Magnificient Force and much more. Some of the best dancers at that time were guys like Chino, Brian, German (Incredible Breakers), Dr. Love (Master Mind), Flip (Scrambling Feet), Tiny (Incredible Body Mechanic) and many more. The biggest rivalries during that time were between Rock Steady Crew and NYC Breakers as well as between Rock Steady Crew and Dynamic Rockers. The early 80's battles between these crews attracted the attention of the media.

In '81 the ABC News showed a performance of Rock Steady Crew at Lincoln Center. Then in '82 a battle between Rock Steady Crew and Dynamic Rockers was recorded for the film/documentary "Style Wars" which was later on also aired nationally on PBS and that's how Breakin found the way to the West Coast of the USA. In the same year the "Roxy" formerly known as a Rollerskate Disco was reopened as a Hip Hop Club.

In '83 the movie "Flashdance" came into the cinemas and the video clip of Malcolm McLarens "Buffalo Gals" was showed on TV. Rock Steady Crew was featured in both productions and they were seen all over the world because of the success of this movie and this song. That was the release for the media explosion in most of the countries all around the world. For everybody Breakin was something new, something that has never been seen before, something that was really spectacular and fascinating. Still in the same year the movie "Wild Style" came out and to promote it the "Wild Style" - tour took place, which was the first international tour featuring Hip Hop culture. The MCs, DJs, Graffiti artists and Breakers went also to London and Paris and this was the first time that Breaking could be seen "live" in Europe.

In '84 the movie "Beat Street" came out which featured Rock Steady Crew, NYC Breakers and Magnificent Force and at the closing ceremonies of the LA Olympic Summer Games over 100 B-Boys and B-Girls did a performance! Still in the same year the "Swatch Watch NYC Fresh Tour" took place and the movie "Breakin" was shot and a year later in '85 also "Breakin 2: Electric Boogaloo". Both were filmed at the nightclub called "Radio" (later "Radiotron") in LA and they showed what was going on at the WestCoast of the USA.

Breakin became more and more a trend and B-Boys appeared in commercials (for milk, Right Guard, Burger King,..) and TV shows (Fame, That's Incredible!, David Letterman,..). B-Boys were even honoured guests of the prince of Bahrain and of Queen Elizabeth. '85 was also the release of "Electro Rock" - a video which was filmed at a party in the "Hippodome" in London and which showed the UK Hip Hop Scene (with guests from the USA). In '86 the UK FRESH took place in the Wembley Arena (London) which was one of the biggest and most historical events at that time.

In '87 for most people and particularly for the media "Breakdance" was played out. Only very few dancers kept on practicing and dancing seriously, not only in New York but all around the world.

More history coming soon...

(Resources: Word of mouth, interviews and articles of Fabel & Mr Wiggles)

RELATED DANCES

Breaking was and is influenced by many other dancestyles, by gymnastics and even also very strongly by eastern material art moves.

Despite of many rumours and opinions Breaking didn't originate from Capoeira but during the last few years many moves, steps and freezes of this Brazilian (fight-) dance have inspired more and more B-Girls and B-Boys who integrated them into their dance. [read more]

A special dancestyle which is very often used by B-Boys (during their toprock or/and for battling) and which originated in Brooklyn (NYC) is Uprocking. [read more]

In the early/mid 80ies "Breakdance" was often mixed and presented by the media together with Boogaloo, Popping, Robotting, Strutting, Waving and other funk dance styles. Although these dance styles were more and more adopted into the hip-hop movement, they were created in the West Coast during the Funk Era and its roots and history are fundamentally different from B-Boying.

History of Popping and Boogaloo

History of (Campbel-)Locking

© copyright 1986-2010 Spartanic Rockers. All Rights Reserved.

The Roots

Black Lightning

Superstar

Louis Allen, a married, African-American business owner in Liberty, Mississippi, was shot and killed after attempting to register to vote on January 31st 1964. His murder has gone unsolved for over 50 years.

The motive behind Allen’s murder is thought to be racism and a fear of what the he was going to say to federal officials about the murder of Herbert Lee — a man who had been shot by a white state legislator three years previous.

Many believe Allen’s killer was Daniel Jones — the county sheriff at the time, and when Allen’s cold case was reopened in 2007 and again in 2011, both investigating parties came to the same conclusion: Jones had in fact killed Allen; and while this is now the generally accepted theory, Louis Allen’s senseless murder is still, officially, unsolved.

Black Lightning

Superstar

First known female firefighter

Drawing of Molly Williams pulling fire pump through a snow storm in 1818

A slave named Molly Williams was the first known female firefighter in the United States. Little is known about her life, but female firefighters know her heroic story.

Owned by a New York merchant named Benjamin Aymar, Williams became part of the Oceanus Engine Company firehouse in 1815 and would be known as Volunteer Number 11. The members of the house credited her for being as tough as the male firefighters. She would fight amongst them in a calico dress and checked apron.

Besides the bucket brigades, Molly pulled the pumper to fires through the deep snowdrifts of the blizzard of 1818 to save towns. On December 27, 1819, the Fire Department reported that the fire buckets were rapidly being superseded by the use of hose, so the era of fire buckets ended.

Even as a slave, Williams had gained the respect of her fellow firefighters. Her story and strength paved the way for other women, including one the first paid Black female firefighters and the most tenured in the country – Toni McIntosh of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who served for over 11 years.

Today there are many African-American women working as career firefighters and officers in the United States, along with a number of counterparts in the volunteer ranks. The African American Fire Fighter Museum is a non-profit organization dedicated to collecting, conserving and sharing the heritage of African American firefighters.

The Museum is housed at old Fire Station 30. This station, which was one of two segregated fire stations in Los Angeles, between 1924 and 1955, was established in 1913, to serve the Central Ave community.

Drawing of Molly Williams pulling fire pump through a snow storm in 1818

A slave named Molly Williams was the first known female firefighter in the United States. Little is known about her life, but female firefighters know her heroic story.

Owned by a New York merchant named Benjamin Aymar, Williams became part of the Oceanus Engine Company firehouse in 1815 and would be known as Volunteer Number 11. The members of the house credited her for being as tough as the male firefighters. She would fight amongst them in a calico dress and checked apron.

Besides the bucket brigades, Molly pulled the pumper to fires through the deep snowdrifts of the blizzard of 1818 to save towns. On December 27, 1819, the Fire Department reported that the fire buckets were rapidly being superseded by the use of hose, so the era of fire buckets ended.

Even as a slave, Williams had gained the respect of her fellow firefighters. Her story and strength paved the way for other women, including one the first paid Black female firefighters and the most tenured in the country – Toni McIntosh of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who served for over 11 years.

Today there are many African-American women working as career firefighters and officers in the United States, along with a number of counterparts in the volunteer ranks. The African American Fire Fighter Museum is a non-profit organization dedicated to collecting, conserving and sharing the heritage of African American firefighters.

The Museum is housed at old Fire Station 30. This station, which was one of two segregated fire stations in Los Angeles, between 1924 and 1955, was established in 1913, to serve the Central Ave community.

Last edited:

Black Lightning

Superstar

Homer G. Phillips Hospital was built in the 1930s to serve the black community in St. Louis, Missouri. It was the city’s only hospital for African-Americans until 1955 when city hospitals were desegregated. It was one of the few hospitals in the United States where black Americans could train as doctors and nurses, and by 1961, Homer G. Phillips Hospital had trained the largest number of black doctors and nurses in the world.

Black Lightning

Superstar

1960s Joan Dorsey was the first African-American flight attendant hired to work for American Airlines.