http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32527645

Vietnam PM: US 'committed barbarous crimes' during war

Vietnam's prime minister has spoken of "countless barbarous crimes" committed by the US during the Vietnam War.

Nguyen Tan Dung was speaking at an event in Ho Chi Minh City to mark the 40th anniversary of the end of the war.

On 30 April 1975 the city - which was then called Saigon and was the capital of South Vietnam - was captured by communist troops from the North.

Three million Vietnamese, and 58,000 US soldiers died in the war. But the US and Vietnam now have diplomatic ties.

Speaking in front of the former Presidential Palace Mr Dung said: "[The US] committed countless barbarous crimes, caused immeasurable losses and pain to our people and country".

"Our homeland had to undergo extremely serious challenges."

Some in Vietnam are still suffering from deformities and the lasting effects of the dioxin Agent Orange, sprayed by the US Air Force into the thick jungle used as cover by northern guerrilla forces.

Soldiers and veterans

Eventually the US-backed South was defeated and the North's tanks smashed through the gates of the palace in Ho Chi Minh City ending the conflict. The reunification process was completed the next year.

Vietnam's relationship with the US has changed significantly since then. They now have diplomatic ties and are trade partners.

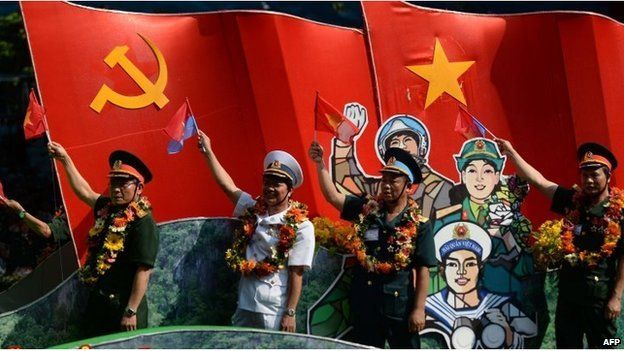

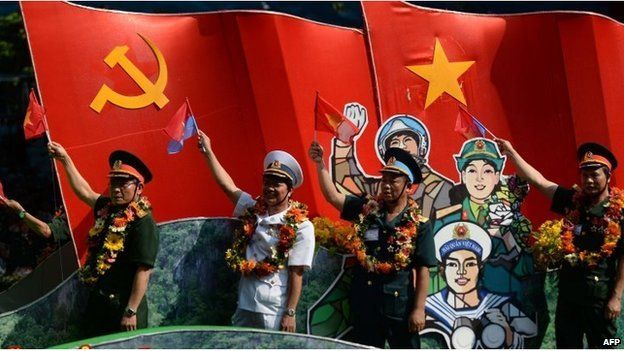

On Thursday, regiments of soldiers and war veterans took park in an elaborate commemorative parade to pay tribute to those who fought and died in the long conflict.

Many of those taking part in the events are too young to remember the war

It was a fun and festive atmosphere

Troops paraded through the city in dress uniform

Huong Ly, BBC World Service

When I was 16 months old my mother went to war. Duong Thi Xuan Quy became North Vietnam's first female war correspondent, but - and it's a familiar story in a country where three million died - she never came home.

We are still searching for her remains.

Read the full story: Searching for the truth about my mother

The Vietnamese national flag was widely visible

War veterans also took part in the parade

The North's victory reunited Vietnam under the communist government.

The war was very divisive in the US as well, as it was the first to be extensively covered by US TV. It was also the first to be lost by a modern global superpower.

Hundreds of thousands of people left the South in the years that followed the war, some risking their lives on dangerous boat journeys. Most of them ended up resettling in the US, UK, France and other countries.

The Vietnam War

1954 - Geneva Accords signed dividing Vietnam in two - the communist North helps guerrillas in the South fight US backed Southern troops

1964 - US bombs targets in North Vietnam

1965 - The first US combat troops arrive in Vietnam

1973 - The Paris Peace Accords on "Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam" are signed, officially ending direct US involvement - but fighting between North and South continues

30 April 1975 - North Vietnamese troops enter Saigon - South Vietnam is controlled by communist forces and the country is reunited ending the war

Vietnam PM: US 'committed barbarous crimes' during war

Vietnam's prime minister has spoken of "countless barbarous crimes" committed by the US during the Vietnam War.

Nguyen Tan Dung was speaking at an event in Ho Chi Minh City to mark the 40th anniversary of the end of the war.

On 30 April 1975 the city - which was then called Saigon and was the capital of South Vietnam - was captured by communist troops from the North.

Three million Vietnamese, and 58,000 US soldiers died in the war. But the US and Vietnam now have diplomatic ties.

Speaking in front of the former Presidential Palace Mr Dung said: "[The US] committed countless barbarous crimes, caused immeasurable losses and pain to our people and country".

"Our homeland had to undergo extremely serious challenges."

Some in Vietnam are still suffering from deformities and the lasting effects of the dioxin Agent Orange, sprayed by the US Air Force into the thick jungle used as cover by northern guerrilla forces.

Soldiers and veterans

Eventually the US-backed South was defeated and the North's tanks smashed through the gates of the palace in Ho Chi Minh City ending the conflict. The reunification process was completed the next year.

Vietnam's relationship with the US has changed significantly since then. They now have diplomatic ties and are trade partners.

On Thursday, regiments of soldiers and war veterans took park in an elaborate commemorative parade to pay tribute to those who fought and died in the long conflict.

Many of those taking part in the events are too young to remember the war

It was a fun and festive atmosphere

Troops paraded through the city in dress uniform

Huong Ly, BBC World Service

When I was 16 months old my mother went to war. Duong Thi Xuan Quy became North Vietnam's first female war correspondent, but - and it's a familiar story in a country where three million died - she never came home.

We are still searching for her remains.

Read the full story: Searching for the truth about my mother

The Vietnamese national flag was widely visible

War veterans also took part in the parade

The North's victory reunited Vietnam under the communist government.

The war was very divisive in the US as well, as it was the first to be extensively covered by US TV. It was also the first to be lost by a modern global superpower.

Hundreds of thousands of people left the South in the years that followed the war, some risking their lives on dangerous boat journeys. Most of them ended up resettling in the US, UK, France and other countries.

The Vietnam War

1954 - Geneva Accords signed dividing Vietnam in two - the communist North helps guerrillas in the South fight US backed Southern troops

1964 - US bombs targets in North Vietnam

1965 - The first US combat troops arrive in Vietnam

1973 - The Paris Peace Accords on "Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam" are signed, officially ending direct US involvement - but fighting between North and South continues

30 April 1975 - North Vietnamese troops enter Saigon - South Vietnam is controlled by communist forces and the country is reunited ending the war