get these nets

Veteran

*excerpts from article

apnews.com

apnews.com

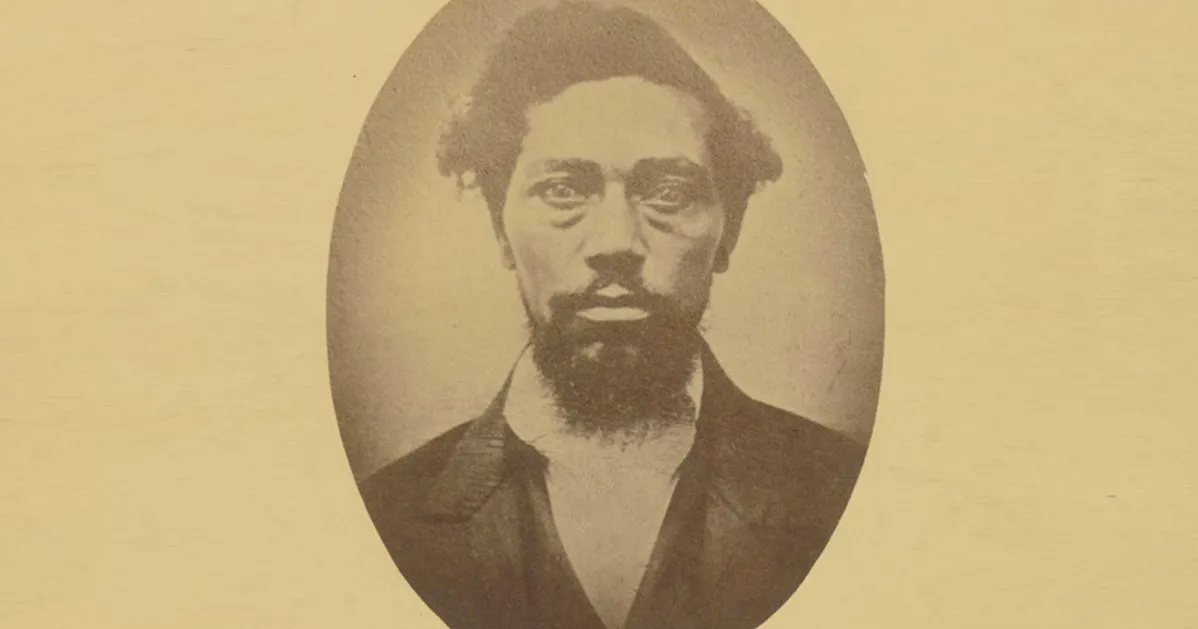

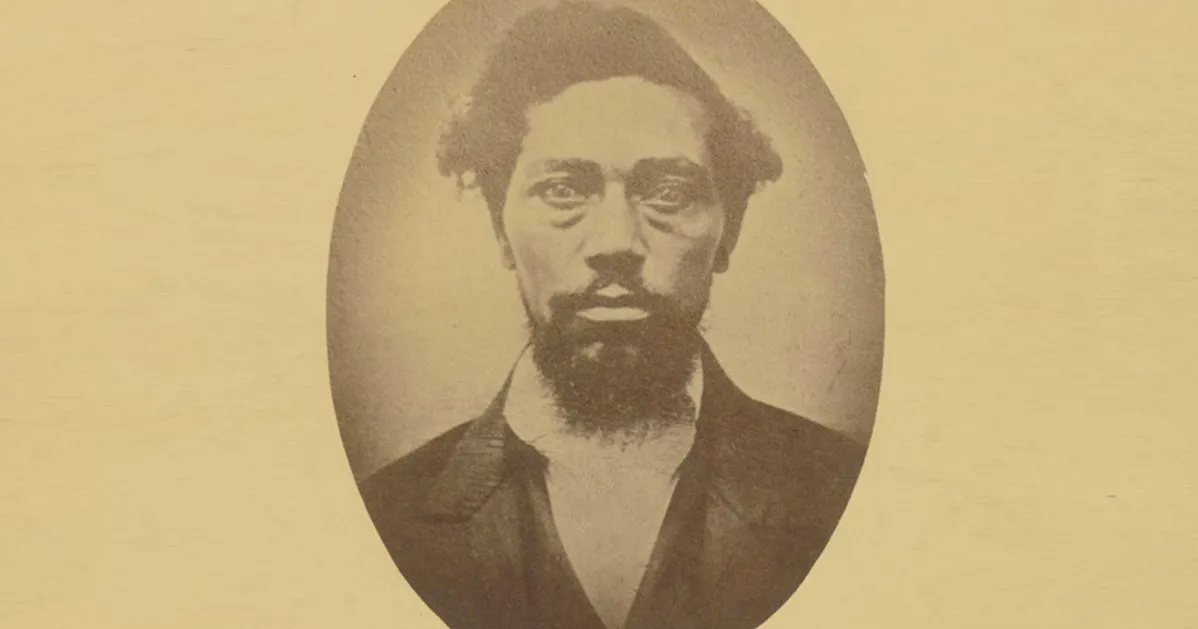

Dangerfield Newby10/06/25

HARPERS FERRY, W.Va. (AP) — By the roiling rapids of converging rivers, President Donald Trump’s campaign to have the government tell a happier story of American history confronts its toughest challenge. There is no positive spin to be put on slavery.

At frozen-in-time Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, people in the National Park Service are navigating shoals that federal storytellers across the nation must now negotiate. How do you tell the truth if it might not be the whole truth?

As part of a broader Trump directive reaching across the government and the country, the park service is under orders to review interpretive materials at all its historical properties and remove or alter descriptions that “inappropriately disparage Americans past or living” or otherwise sully the American story. This comes as the Republican president has complained about institutions that go too deep, in his view, on “how bad slavery was.”

It’s too soon to know whether his directive is causing the arc of history to bend toward sanitized revisionism. There are at least scattered indications that the reviewers may be treading carefully in reshaping America’s core stories.

“You can’t wipe that,” she told The Associated Press. “You can’t erase that. It’s our obligation to not let that be erased.”

At some parks, employees on the ground told the AP, brochures with references to “enslavers” have been pulled for revision and everything is getting a hard look.

Yet in the guided tour about Brown’s raid, the story presented about slavery remains unflinching.

A far more complex story was told in a recent guided tour at Harpers Ferry. Brown was held up as a transformational figure whose audacious and deadly raid swelled Northern anti-slavery sentiment on the cusp of a war that produced “a new birth of freedom.”

So said the park ranger speaking to a crowd on a bluff overlooking where the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers smash together like the forces of North and South once did.

Wheeler is a descendant of Dangerfield Newby, the first of Brown’s raiders to die in the Harpers Ferry fighting.

A child of a white enslaver and a Black enslaved woman, Newby was freed in Ohio while his common law wife, Harriet, and their children remained in bondage in Virginia. He was saving up to buy and liberate them when he joined Brown’s band of men.

Newby was shot dead by a musket loaded with a railroad spike in a street battle between townspeople and the raiders. His body was mutilated. Wheeler said the chilling scene with her ancestor and the broader experience of millions of enslaved people are as much a part of the American story as the uplifting episodes.

This country must know “what really made America,” Wheeler said. “Who bled, whose blood is in these stones and on these streets. Harpers Ferry is a huge thread in that tapestry.”

So is Brown a hero in the eyes of his descendant? “Yes,” says Wheeler, because he gave up everything, including his life, for a monumental cause. But “he’s not a superhero. He’s a flawed character.”

He’s complicated. Like history itself.

At America's national parks in the Trump era, the arc of history bends toward revisionism

The National Park Service under President Donald Trump is looking to reshape what it tells Americans about their history.

Dangerfield Newby

HARPERS FERRY, W.Va. (AP) — By the roiling rapids of converging rivers, President Donald Trump’s campaign to have the government tell a happier story of American history confronts its toughest challenge. There is no positive spin to be put on slavery.

At frozen-in-time Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, people in the National Park Service are navigating shoals that federal storytellers across the nation must now negotiate. How do you tell the truth if it might not be the whole truth?

As part of a broader Trump directive reaching across the government and the country, the park service is under orders to review interpretive materials at all its historical properties and remove or alter descriptions that “inappropriately disparage Americans past or living” or otherwise sully the American story. This comes as the Republican president has complained about institutions that go too deep, in his view, on “how bad slavery was.”

It’s too soon to know whether his directive is causing the arc of history to bend toward sanitized revisionism. There are at least scattered indications that the reviewers may be treading carefully in reshaping America’s core stories.

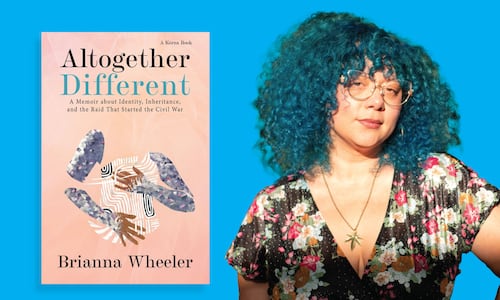

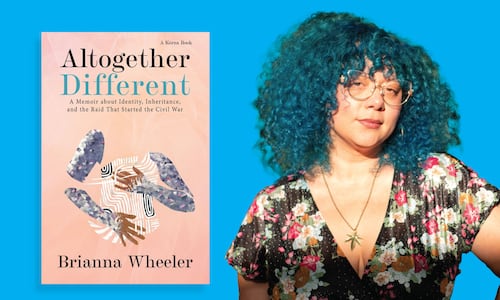

Descendant of a John Brown raider wants the whole truth

Brianna Wheeler hopes they stay true to history. She is a direct descendant of one of abolitionist John Brown’s anti-slavery raiders who laid siege to the U.S. armory at Harpers Ferry in a bloody 1859 assault that set the stage for the Civil War. The shame of slavery must not be ignored, she said.“You can’t wipe that,” she told The Associated Press. “You can’t erase that. It’s our obligation to not let that be erased.”

At some parks, employees on the ground told the AP, brochures with references to “enslavers” have been pulled for revision and everything is getting a hard look.

Yet in the guided tour about Brown’s raid, the story presented about slavery remains unflinching.

A far more complex story was told in a recent guided tour at Harpers Ferry. Brown was held up as a transformational figure whose audacious and deadly raid swelled Northern anti-slavery sentiment on the cusp of a war that produced “a new birth of freedom.”

So said the park ranger speaking to a crowd on a bluff overlooking where the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers smash together like the forces of North and South once did.

Was John Brown a hero?

Whether Brown is a hero is explicitly left for you to decide. This fierce abolitionist had plenty of blood on his hands even before he set foot in Harpers Ferry. Witnesses said he and his band killed five pro-slavery men and boys in a Kansas massacre sparked by enmity between pro-slavery and anti-slavery Kansans..

Wheeler is a descendant of Dangerfield Newby, the first of Brown’s raiders to die in the Harpers Ferry fighting.

A child of a white enslaver and a Black enslaved woman, Newby was freed in Ohio while his common law wife, Harriet, and their children remained in bondage in Virginia. He was saving up to buy and liberate them when he joined Brown’s band of men.

Newby was shot dead by a musket loaded with a railroad spike in a street battle between townspeople and the raiders. His body was mutilated. Wheeler said the chilling scene with her ancestor and the broader experience of millions of enslaved people are as much a part of the American story as the uplifting episodes.

This country must know “what really made America,” Wheeler said. “Who bled, whose blood is in these stones and on these streets. Harpers Ferry is a huge thread in that tapestry.”

So is Brown a hero in the eyes of his descendant? “Yes,” says Wheeler, because he gave up everything, including his life, for a monumental cause. But “he’s not a superhero. He’s a flawed character.”

He’s complicated. Like history itself.