Ed Smith And The Imagination Machine: The Untold Story Of A Black Video Game Pioneer

Ed Smith And The Imagination Machine: The Untold Story Of A Black Video Game Pioneer

At APF in the 1970s, as the second-known African-American video game engineer, he helped create an industry.

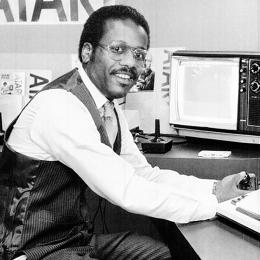

Ed Smith at the Winter CES show in 1981 with the Imagination Machine II personal computer

Benj Edwards 09.02.16 12:00 AM

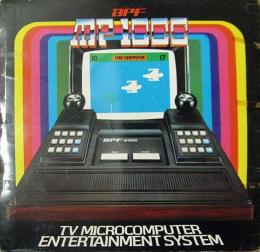

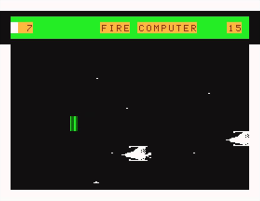

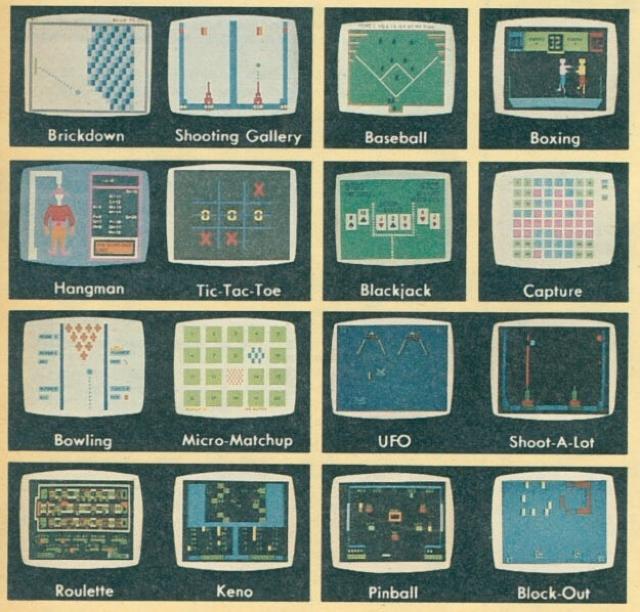

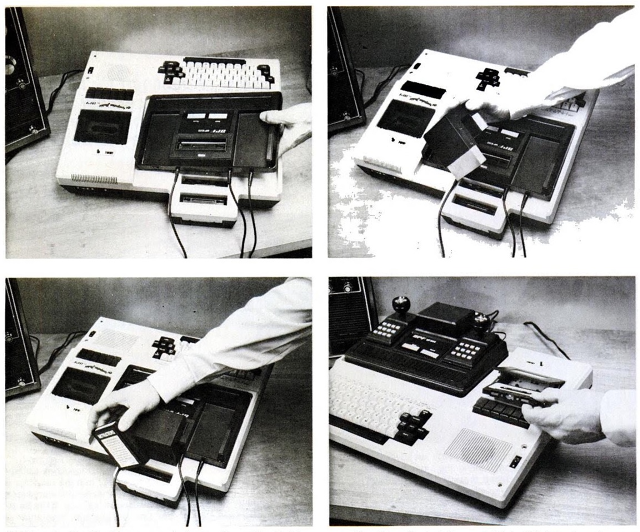

Thirty-seven years ago, New York-based APF Electronics, Inc. released The Imagination Machine, a hybrid video game console and personal computer designed to make a consumer's first experience with computing as painless and inexpensive as possible.

APF's playful computer (and its game console, the MP1000) never rivaled the impact of products from Apple or Atari, but they remain historically important because of the man who cocreated them: Ed Smith, one of the first African-American electronics engineers in the video game industry. During a time when black Americans struggled for social justice, Manhattan-based APF hired Smith to design the core element of its future electronics business.

What it took to get there, for both APF and Smith, is a story worth recounting—and one that, until now, has never been told in full.

Edward Lee Smith was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1954. He grew up in Brownsville, an impoverished neighborhood within the borough. His parents moved there from Mississippi a few years prior, and they weren't alone. Between about 1910 and 1970, millions of black families like the Smiths fled north in a Great Migration, as historians now call it, to escape the terrors of the American South during the Jim Crow era.

What his parents found when they got to New York wasn't much more promising than the South: Government policies and widespread racism kept black residents concentrated in small areas of low opportunity and high poverty. Places like Brownsville were the result. The neighborhood had once been primarily occupied by Jews, but later became known as a black ghetto, replete with scenes of crime and misfortune that unfolded every day. It was in this environment that Ed Smith came of age, the third eldest of six brothers and sisters, in a public housing development called Nobel Drew Ali Plaza. His mother was a domestic, and his father, an Army veteran, drove trucks for a living.

Early on, Smith's father told the younger Smith not to expect any greater aspirations for himself. "Get your chauffeur’s license so you can learn how to drive a truck," Smith recalls him saying, "because that’s all you’re ever going to do." And yet such expectations could not suppress Ed Smith's intense curiosity about how things worked. He began taking apart everything he could, and he soon taught himself to repair basic electrical gadgets like toasters and irons. Later, he moved on to radio receivers and TV sets. Smith's electronics skills came in handy as he began doing odd jobs around the neighborhood to help make ends meet for his family. At times, he largely provided for himself.

Through exposure to books and TV, Smith learned about the larger world outside of Brownsville. He devoured epic science fiction works and titles by black intellectuals such as Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and the works of W.E.B. Du Bois. As his knowledge of the world grew, Smith began to feel like Brownsville was his personal cage, holding him back from greater opportunities. He recalls the many times he sat at his window, watching the traffic on the busy four-lane street outside. "My only wish was to be sitting in one of those cars, driving down Eastern Parkway," he says. "Anywhere, any direction, I didn't care. I just didn't want to be there."

It was a tough life, but he tried his best to steer his own fate. At age 13, Smith recalls waking up to a commotion, his sisters and brothers crying. In another room, he found his mother on the floor, his father pummeling her with fierce blows. Smith tried to pull his dad off, but the elder Smith knocked him unconscious. When the teen came to, he grabbed a frying pan from the kitchen and knocked his father out. "I dragged him out of the house and locked the door," recalls Smith. "That was the last time my father ever came into our home."

1968: Creation And Chaos

In January 1968, two brothers named Albert and Philip Friedman, both veterans of the consumer electronics industry and Asian import specialists, founded a technology company named after their initials: APF Electronics, Inc. The new firm opened an office on Madison Avenue in Manhattan and got to work quickly, making deals to bring in the latest transistorized calculators and stereos from Japan.

Albert Friedman, the company's first president, then in his 60s, had previously worked for Olympic Radio, then later served as president of Delmonico International—the first company to import Sony products to the United States. His brother Philip grew up in prewar Japan, steeped in Asian culture, and had for decades been an essential liaison to U.S. firms that sought to do business with the Far East.

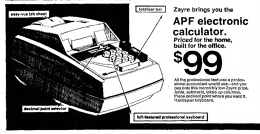

A 1972 ad for an APF calculator

The pair hired other Delmonico veterans to fill out APF's initial team, including Seymour "Sy" Lipper, who took on a marketing role, and Irving Boilen, an electronics engineer that would serve as the head of their new engineering department.

On the broader American stage, 1968 marked a tumultuous low point in a decade that saw rapid social and technological change. While the Vietnam War weighed heavily on the nation's collective conscience, it was a domestic event that set the chaotic tone for the rest of the year: On April 4, James Earl Ray shot and killed Martin Luther King, Jr., as he stood on his motel balcony in Memphis.

The assassination of the U.S.'s most famous proponent of black rights triggered riots in many communities around the country, including Brownsville. The day after King was killed, 14-year-old Ed Smith sat on a street corner, watching in disgust. "I remember all of the looting going on around me," he recalls. "People were taking bricks and throwing them into white people's cars. It was mass rioting." The experience solidified his resolve: He was going to find a path out of the projects.

Smith's friends were skeptical of his passionate interest in electronics. "When they heard what I was doing, they would say, 'You would never understand that, a black guy can't do this kind of thing. It's not your world. They will laugh you out of the room,'" he says. The negative remarks only served as a challenge to Smith, who sought to prove them wrong.

During his last year of high school, Smith met his future wife, Sheila, and unexpectedly found himself becoming a father at age 18. The desire to provide for his family intensified Smith's drive, and after graduation, he started working full time doing electrical odd jobs like wiring security systems.

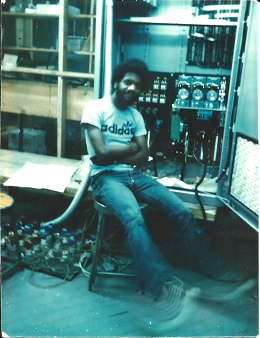

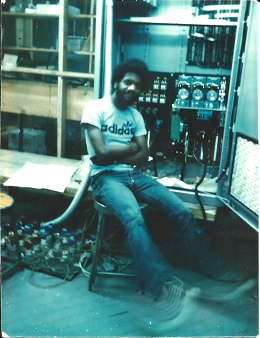

Ed Smith at work at traffic-signal maker Marbelite circa 1975

In 1972, Smith moved to Coney Island and landed a position at Brooklyn-based Marbelite, one of the nation's largest manufacturers of traffic signals. The job gave Smith his first taste of digital electronics technology, which would drive consumer electronics of the 1970s, '80s, and beyond.

Behind every traffic signal is a device called a traffic controller—a timer that keeps track of when to turn on and off certain lights. Prior to the 1970s, most controllers relied on electromechanical parts, but the boom in solid-state electronics saw the controllers become transistorized in the early 1970s. In 1971, Intel had introduced the first commercial single-chip microprocessor, launching a new era in electronics. Just as other industries scrambled to incorporate the new technology into their products, it wasn't long before Marbelite wanted to use the power of a microprocessor to control traffic signals.

To that end, Marbelite paid for Smith, who was then working as a technician, to attend local vocational classes on microprocessor-based circuit design. He learned to program the brand-new Fairchild F8 microprocessor (coincidentally the same chip used in the Fairchild Channel F, the first cartridge-based video game system in 1976). The classes brought big dividends to Smith, who soon leveraged the knowledge to get a taste of life in other parts of the Big Apple.

Of Calculators And Video Games

By 1972, APF Electronics had established itself as a leading manufacturer of desktop electronic calculators. In fact, the firm was doing so well that it contracted Sy Lipper's brother, Martin "Marty" Lipper, as a specialist to take the company public that November. Looking back, Marty (who joined APF full time as its CFO in 1973) emphasizes the role of calculators in the company's early success. "We built 70% of all the calculators ever sold at Sears in those days," he recalls. "The same goes for Montgomery Ward."

Calculators would carry APF's business forward until the next great revolution in consumer electronics came along: video games. Just as APF was going public in 1972, a young California company called Atari made waves nationwide with Pong, an arcade video game sensation that soon spawned dozens of shameless rip-off games and launched a wider arcade video game industry. Ironically, Pong itself was a shameless (but improved) rip-off of the first home video game system, the Magnavox Odyssey, which launched just a few months earlier.

In December 1975, Atari released the home console version of Pong through Sears under its Tele-Games label, and it proved wildly successful. Like it had done in the arcades, Pong as a home product inspired dozens of knock-offs, most of which were built using a custom "Pong-on-a-chip" integrated circuit created by General Instruments called the AY-3-8500. The mass production and general availability of this chip, and several follow-ups, made the engineering of dedicated "ball-and-paddle" consoles almost trivial affairs, with more work going into their plastic cases than into the electronics within.

APF's TV Fun video game console

In 1976, APF became one of dozens of firms that jumped headfirst into the home video game market, releasing its first Pong-like decidated console, the TV Fun. It was a sleek, compact, plastic cabinet with faux woodgrain and silver trim and two built-in rotary knobs that contained four built-in variations of the simple ball-and-paddle game. While the TV Fun utilized the same Pong-on-a-chip circuit that many other manufacturers used in their own clone consoles, APF's model quickly became one of the best selling on the market, moving 400,000 units within its first year—a stunning figure at the time.

Over the next two years, APF followed the first TV Fun with several improved models that added more games and a light gun, although sales dropped with each successive unit as the market became increasingly saturated with Pong-like consoles.

APF also found, as other companies did, that it became prohibitively risky to keep releasing new dedicated consoles—which often needed their own distinctive cases, circuitry, and marketing campaigns—to accommodate new types of video games. The solution to this problem first entered the market in 1976 with the Channel F, which was codesigned by an African-American engineer, Jerry Lawson. The Channel F approach allowed the sale of one universal console player device and many smaller, less expensive game cartridges that would add lasting appeal to the system.

An interchangeable, programmable approach to video games required the games to be written as software and run through a microprocessor—in other words, it meant designing a computerized video game system. From APF's point of view, creating such a console would require specialized expertise that few engineers at the company had developed. That led to the search for a new hire who could help design a new console that would lead APF into the next generation. Thanks to Marbelite, they would soon find their man.

Ed Smith And The Imagination Machine: The Untold Story Of A Black Video Game Pioneer

At APF in the 1970s, as the second-known African-American video game engineer, he helped create an industry.

Ed Smith at the Winter CES show in 1981 with the Imagination Machine II personal computer

Benj Edwards 09.02.16 12:00 AM

Thirty-seven years ago, New York-based APF Electronics, Inc. released The Imagination Machine, a hybrid video game console and personal computer designed to make a consumer's first experience with computing as painless and inexpensive as possible.

APF's playful computer (and its game console, the MP1000) never rivaled the impact of products from Apple or Atari, but they remain historically important because of the man who cocreated them: Ed Smith, one of the first African-American electronics engineers in the video game industry. During a time when black Americans struggled for social justice, Manhattan-based APF hired Smith to design the core element of its future electronics business.

What it took to get there, for both APF and Smith, is a story worth recounting—and one that, until now, has never been told in full.

Edward Lee Smith was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1954. He grew up in Brownsville, an impoverished neighborhood within the borough. His parents moved there from Mississippi a few years prior, and they weren't alone. Between about 1910 and 1970, millions of black families like the Smiths fled north in a Great Migration, as historians now call it, to escape the terrors of the American South during the Jim Crow era.

What his parents found when they got to New York wasn't much more promising than the South: Government policies and widespread racism kept black residents concentrated in small areas of low opportunity and high poverty. Places like Brownsville were the result. The neighborhood had once been primarily occupied by Jews, but later became known as a black ghetto, replete with scenes of crime and misfortune that unfolded every day. It was in this environment that Ed Smith came of age, the third eldest of six brothers and sisters, in a public housing development called Nobel Drew Ali Plaza. His mother was a domestic, and his father, an Army veteran, drove trucks for a living.

Early on, Smith's father told the younger Smith not to expect any greater aspirations for himself. "Get your chauffeur’s license so you can learn how to drive a truck," Smith recalls him saying, "because that’s all you’re ever going to do." And yet such expectations could not suppress Ed Smith's intense curiosity about how things worked. He began taking apart everything he could, and he soon taught himself to repair basic electrical gadgets like toasters and irons. Later, he moved on to radio receivers and TV sets. Smith's electronics skills came in handy as he began doing odd jobs around the neighborhood to help make ends meet for his family. At times, he largely provided for himself.

Through exposure to books and TV, Smith learned about the larger world outside of Brownsville. He devoured epic science fiction works and titles by black intellectuals such as Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and the works of W.E.B. Du Bois. As his knowledge of the world grew, Smith began to feel like Brownsville was his personal cage, holding him back from greater opportunities. He recalls the many times he sat at his window, watching the traffic on the busy four-lane street outside. "My only wish was to be sitting in one of those cars, driving down Eastern Parkway," he says. "Anywhere, any direction, I didn't care. I just didn't want to be there."

It was a tough life, but he tried his best to steer his own fate. At age 13, Smith recalls waking up to a commotion, his sisters and brothers crying. In another room, he found his mother on the floor, his father pummeling her with fierce blows. Smith tried to pull his dad off, but the elder Smith knocked him unconscious. When the teen came to, he grabbed a frying pan from the kitchen and knocked his father out. "I dragged him out of the house and locked the door," recalls Smith. "That was the last time my father ever came into our home."

1968: Creation And Chaos

In January 1968, two brothers named Albert and Philip Friedman, both veterans of the consumer electronics industry and Asian import specialists, founded a technology company named after their initials: APF Electronics, Inc. The new firm opened an office on Madison Avenue in Manhattan and got to work quickly, making deals to bring in the latest transistorized calculators and stereos from Japan.

Albert Friedman, the company's first president, then in his 60s, had previously worked for Olympic Radio, then later served as president of Delmonico International—the first company to import Sony products to the United States. His brother Philip grew up in prewar Japan, steeped in Asian culture, and had for decades been an essential liaison to U.S. firms that sought to do business with the Far East.

A 1972 ad for an APF calculator

The pair hired other Delmonico veterans to fill out APF's initial team, including Seymour "Sy" Lipper, who took on a marketing role, and Irving Boilen, an electronics engineer that would serve as the head of their new engineering department.

On the broader American stage, 1968 marked a tumultuous low point in a decade that saw rapid social and technological change. While the Vietnam War weighed heavily on the nation's collective conscience, it was a domestic event that set the chaotic tone for the rest of the year: On April 4, James Earl Ray shot and killed Martin Luther King, Jr., as he stood on his motel balcony in Memphis.

The assassination of the U.S.'s most famous proponent of black rights triggered riots in many communities around the country, including Brownsville. The day after King was killed, 14-year-old Ed Smith sat on a street corner, watching in disgust. "I remember all of the looting going on around me," he recalls. "People were taking bricks and throwing them into white people's cars. It was mass rioting." The experience solidified his resolve: He was going to find a path out of the projects.

Smith's friends were skeptical of his passionate interest in electronics. "When they heard what I was doing, they would say, 'You would never understand that, a black guy can't do this kind of thing. It's not your world. They will laugh you out of the room,'" he says. The negative remarks only served as a challenge to Smith, who sought to prove them wrong.

During his last year of high school, Smith met his future wife, Sheila, and unexpectedly found himself becoming a father at age 18. The desire to provide for his family intensified Smith's drive, and after graduation, he started working full time doing electrical odd jobs like wiring security systems.

Ed Smith at work at traffic-signal maker Marbelite circa 1975

In 1972, Smith moved to Coney Island and landed a position at Brooklyn-based Marbelite, one of the nation's largest manufacturers of traffic signals. The job gave Smith his first taste of digital electronics technology, which would drive consumer electronics of the 1970s, '80s, and beyond.

Behind every traffic signal is a device called a traffic controller—a timer that keeps track of when to turn on and off certain lights. Prior to the 1970s, most controllers relied on electromechanical parts, but the boom in solid-state electronics saw the controllers become transistorized in the early 1970s. In 1971, Intel had introduced the first commercial single-chip microprocessor, launching a new era in electronics. Just as other industries scrambled to incorporate the new technology into their products, it wasn't long before Marbelite wanted to use the power of a microprocessor to control traffic signals.

To that end, Marbelite paid for Smith, who was then working as a technician, to attend local vocational classes on microprocessor-based circuit design. He learned to program the brand-new Fairchild F8 microprocessor (coincidentally the same chip used in the Fairchild Channel F, the first cartridge-based video game system in 1976). The classes brought big dividends to Smith, who soon leveraged the knowledge to get a taste of life in other parts of the Big Apple.

Of Calculators And Video Games

By 1972, APF Electronics had established itself as a leading manufacturer of desktop electronic calculators. In fact, the firm was doing so well that it contracted Sy Lipper's brother, Martin "Marty" Lipper, as a specialist to take the company public that November. Looking back, Marty (who joined APF full time as its CFO in 1973) emphasizes the role of calculators in the company's early success. "We built 70% of all the calculators ever sold at Sears in those days," he recalls. "The same goes for Montgomery Ward."

Calculators would carry APF's business forward until the next great revolution in consumer electronics came along: video games. Just as APF was going public in 1972, a young California company called Atari made waves nationwide with Pong, an arcade video game sensation that soon spawned dozens of shameless rip-off games and launched a wider arcade video game industry. Ironically, Pong itself was a shameless (but improved) rip-off of the first home video game system, the Magnavox Odyssey, which launched just a few months earlier.

In December 1975, Atari released the home console version of Pong through Sears under its Tele-Games label, and it proved wildly successful. Like it had done in the arcades, Pong as a home product inspired dozens of knock-offs, most of which were built using a custom "Pong-on-a-chip" integrated circuit created by General Instruments called the AY-3-8500. The mass production and general availability of this chip, and several follow-ups, made the engineering of dedicated "ball-and-paddle" consoles almost trivial affairs, with more work going into their plastic cases than into the electronics within.

APF's TV Fun video game console

In 1976, APF became one of dozens of firms that jumped headfirst into the home video game market, releasing its first Pong-like decidated console, the TV Fun. It was a sleek, compact, plastic cabinet with faux woodgrain and silver trim and two built-in rotary knobs that contained four built-in variations of the simple ball-and-paddle game. While the TV Fun utilized the same Pong-on-a-chip circuit that many other manufacturers used in their own clone consoles, APF's model quickly became one of the best selling on the market, moving 400,000 units within its first year—a stunning figure at the time.

Over the next two years, APF followed the first TV Fun with several improved models that added more games and a light gun, although sales dropped with each successive unit as the market became increasingly saturated with Pong-like consoles.

APF also found, as other companies did, that it became prohibitively risky to keep releasing new dedicated consoles—which often needed their own distinctive cases, circuitry, and marketing campaigns—to accommodate new types of video games. The solution to this problem first entered the market in 1976 with the Channel F, which was codesigned by an African-American engineer, Jerry Lawson. The Channel F approach allowed the sale of one universal console player device and many smaller, less expensive game cartridges that would add lasting appeal to the system.

An interchangeable, programmable approach to video games required the games to be written as software and run through a microprocessor—in other words, it meant designing a computerized video game system. From APF's point of view, creating such a console would require specialized expertise that few engineers at the company had developed. That led to the search for a new hire who could help design a new console that would lead APF into the next generation. Thanks to Marbelite, they would soon find their man.