ogc163

Superstar

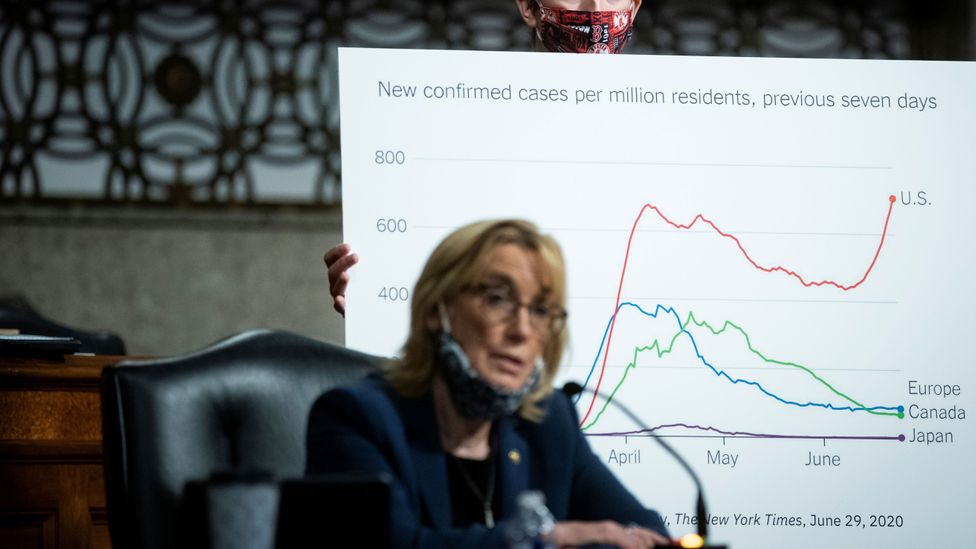

A simple mathematical mistake may explain why many people underestimate the dangers of coronavirus, shunning social distancing, masks and hand-washing.

I

Imagine you are offered a deal with your bank, where your money doubles every three days. If you invest just $1 today, roughly how long will it take for you to become a millionaire?

Would it be a year? Six months? 100 days?

The precise answer is 60 days from your initial investment, when your balance would be exactly $1,048,576. Within a further 30 days, you’d have earnt more than a billion. And by the end of the year, you’d have more than $1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 – an “undecillion” dollars.

If your estimates were way out, you are not alone. Many people consistently underestimate how fast the value increases – a mistake known as the “exponential growth bias” – and while it may seem abstract, it may have had profound consequences for people’s behaviour this year.

A spate of studies has shown that people who are susceptible to the exponential growth bias are less concerned about Covid-19’s spread, and less likely to endorse measures like social distancing, hand washing or mask wearing. In other words, this simple mathematical error could be costing lives – meaning that the correction of the bias should be a priority as we attempt to flatten curves and avoid second waves of the pandemic around the world.

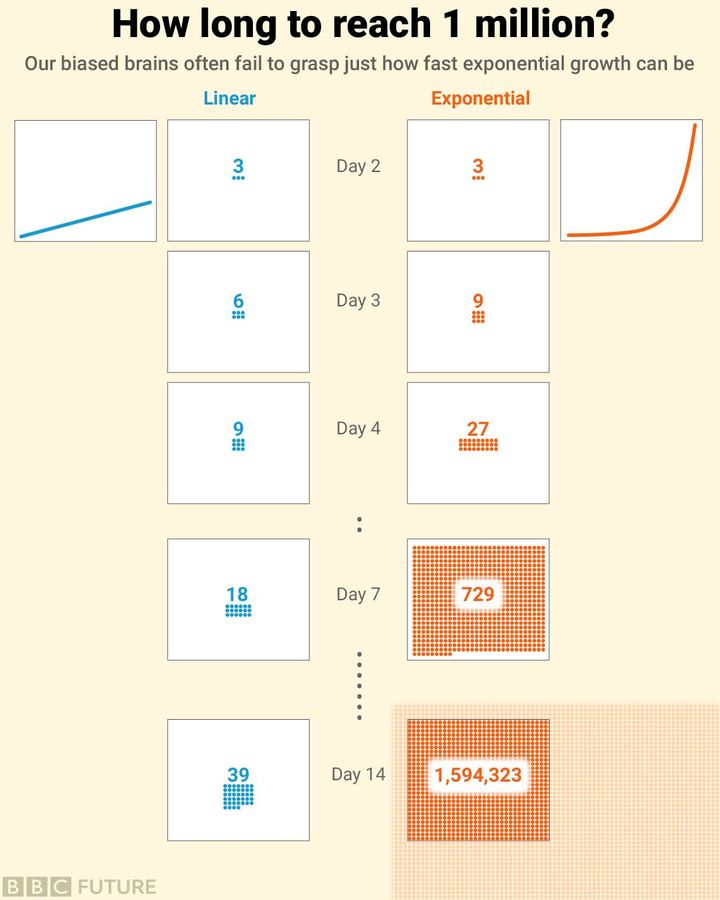

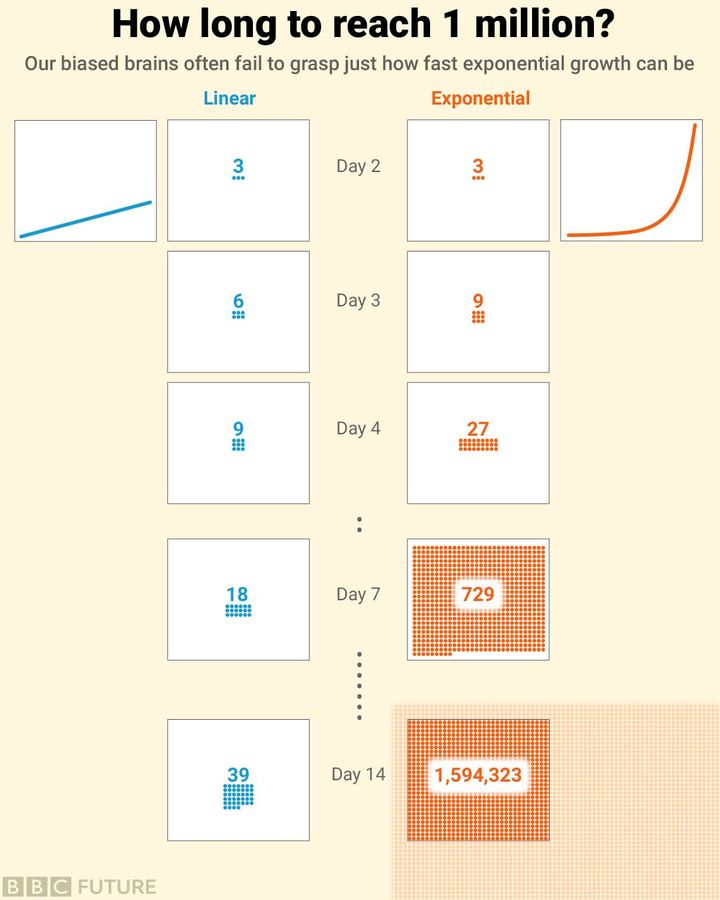

To understand the origins of this particular bias, we first need to consider different kinds of growth. The most familiar is “linear”. If your garden produces three apples every day, you have six after two days, nine after three days, and so on.

Exponential growth, by contrast, accelerates over time. Perhaps the simplest example is population growth; the more people you have reproducing, the faster the population grows. Or if you have a weed in your pond that triples each day, the number of plants may start out low – just three on day two, and nine on day three – but it soon escalates (see diagram, below).

Many people assume that coronavirus spreads in a linear fashion, but unchecked it's exponential (Credit: Nigel Hawtin)

Our tendency to overlook exponential growth has been known for millennia. According to an Indian legend, the brahmin Sissa ibn Dahir was offered a prize for inventing an early version of chess. He asked for one grain of wheat to be placed on the first square on the board, two for the second square, four for the third square, doubling each time up to the 64th square. The king apparently laughed at the humility of ibn Dahir’s request – until his treasurers reported that it would outstrip all the food in the land (18,446,744,073,709,551,615 grains in total).

It was only in the late 2000s that scientists started to study the bias formally, with research showing that most people – like Sissa ibn Dahir’s king – intuitively assume that most growth is linear, leading them to vastly underestimate the speed of exponential increase.

These initial studies were primarily concerned with the consequences for our bank balance. Most savings accounts offer compound interest, for example, where you accrue additional interest on the interest you have already earned. This is a classic example of exponential growth, and it means that even low interest rates pay off handsomely over time. If you have a 5% interest rate, then £1,000 invested today will be worth £1,050 next year, and £1,102.50 the year after… which adds up to more than £7,000 in 40 years’ time. Yet most people don’t recognise how much more bang for their buck they will receive if they start investing early, so they leave themselves short for their retirement.

If the number of grains on a chess board doubled for each square, the 64th would 'hold' 18 quintillion (Credit: Getty Images)

Besides reducing their savings, the bias also renders people more vulnerable to unfavourable loans, where debt escalates over time. According to one study from 2008, the bias increases someone’s debt-to-income ratio from an average of 23% to an average of 54%.

Surprisingly, a higher level of education does not prevent people from making these errors. Even mathematically trained science students can be vulnerable, says Daniela Sele, who researchs economic decision making at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. “It does help somewhat, but it doesn't preclude the bias,” she says.

I

Imagine you are offered a deal with your bank, where your money doubles every three days. If you invest just $1 today, roughly how long will it take for you to become a millionaire?

Would it be a year? Six months? 100 days?

The precise answer is 60 days from your initial investment, when your balance would be exactly $1,048,576. Within a further 30 days, you’d have earnt more than a billion. And by the end of the year, you’d have more than $1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 – an “undecillion” dollars.

If your estimates were way out, you are not alone. Many people consistently underestimate how fast the value increases – a mistake known as the “exponential growth bias” – and while it may seem abstract, it may have had profound consequences for people’s behaviour this year.

A spate of studies has shown that people who are susceptible to the exponential growth bias are less concerned about Covid-19’s spread, and less likely to endorse measures like social distancing, hand washing or mask wearing. In other words, this simple mathematical error could be costing lives – meaning that the correction of the bias should be a priority as we attempt to flatten curves and avoid second waves of the pandemic around the world.

To understand the origins of this particular bias, we first need to consider different kinds of growth. The most familiar is “linear”. If your garden produces three apples every day, you have six after two days, nine after three days, and so on.

Exponential growth, by contrast, accelerates over time. Perhaps the simplest example is population growth; the more people you have reproducing, the faster the population grows. Or if you have a weed in your pond that triples each day, the number of plants may start out low – just three on day two, and nine on day three – but it soon escalates (see diagram, below).

Many people assume that coronavirus spreads in a linear fashion, but unchecked it's exponential (Credit: Nigel Hawtin)

Our tendency to overlook exponential growth has been known for millennia. According to an Indian legend, the brahmin Sissa ibn Dahir was offered a prize for inventing an early version of chess. He asked for one grain of wheat to be placed on the first square on the board, two for the second square, four for the third square, doubling each time up to the 64th square. The king apparently laughed at the humility of ibn Dahir’s request – until his treasurers reported that it would outstrip all the food in the land (18,446,744,073,709,551,615 grains in total).

It was only in the late 2000s that scientists started to study the bias formally, with research showing that most people – like Sissa ibn Dahir’s king – intuitively assume that most growth is linear, leading them to vastly underestimate the speed of exponential increase.

These initial studies were primarily concerned with the consequences for our bank balance. Most savings accounts offer compound interest, for example, where you accrue additional interest on the interest you have already earned. This is a classic example of exponential growth, and it means that even low interest rates pay off handsomely over time. If you have a 5% interest rate, then £1,000 invested today will be worth £1,050 next year, and £1,102.50 the year after… which adds up to more than £7,000 in 40 years’ time. Yet most people don’t recognise how much more bang for their buck they will receive if they start investing early, so they leave themselves short for their retirement.

If the number of grains on a chess board doubled for each square, the 64th would 'hold' 18 quintillion (Credit: Getty Images)

Besides reducing their savings, the bias also renders people more vulnerable to unfavourable loans, where debt escalates over time. According to one study from 2008, the bias increases someone’s debt-to-income ratio from an average of 23% to an average of 54%.

Surprisingly, a higher level of education does not prevent people from making these errors. Even mathematically trained science students can be vulnerable, says Daniela Sele, who researchs economic decision making at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. “It does help somewhat, but it doesn't preclude the bias,” she says.