OCCAMS_RAZOR

Pro

@blackzeus do you know a lot about algorithm analysis? i may need your help with a proof i have to do for an assignment.

I don't want to argue over definitions, but a statement is a subset of an axiom. E.g., if I say x+y = y+x, then 1+2 = 3 = 2+1 is a subset of that axiom, e.g. a mathematical relation that follows said axiom, but that's not the main point here IMHO>

Godell's theorem is not true for all subsets of axiomatic theory, even if you want to choose natural numbers for example, when is x = x not consistently and completely true?

Self-referential = recursive, which is what I mentioned in my first post. The physical example I gave of an inverse hyperbola shows that it is supposed to trend towards 0 but that is something we ASSUME. You can't consistently and completely prove that at infinity x = 0 because THERE IS NO PHYSICAL QUANTIFICATION OF INFINITY. Infinity is a concept, not a numerical fact. That's the inherent limitation! Every time you use calculus or differential equations you ASSUME certain things to be true in order to solve your problem. Thus, in all but the most trivial axiomatic systems (e.g. addition), you can't consistently and completely prove everything, you have to make ASSUMPTIONS (e.g. limits). All recursive functions that trend towards a value most trend towards either infinity or 0. (using cartesian coordinate system) So we assume that eventually it reaches 0 or infinity in order to simplify our lives. We know it to be true becaue it works out in our calculations, but we can't consistently and completely prove it. Feel free to correct me if you feel I'm wrong.

What is mathematical induction? You have:

1) Base case. E.g. 0+1+2+3+...= (n*(n+1))/2

2) Induction step. Let's declare a set G(n) for all natural numbers. If G(n) is true, then G(n+1) is also true. Using quadratics you can prove that in fact it is also true for G(n+1) as follows:

(0+1+2+..)+(n+1)=((n+1)*((n+1)+1))/2

Now remember for induction we ASSUME (big key word, how in the f*ck is that not a leap of faith?!!) the base case is true, so assuming in fact 0+1+2+3+...= (n*(n+1))/2 is true, we get---->

1)...=(n*(n+1))/2 + (n+1) = ((n+1)*((n+1)+1))/2

2)...((n+1)*((n+1)+1))/2 = (n*(n+1)+(n+1)+(n+1))/2 = (n*(n+1)+2(n+1))/2 (I did that by multiplying the numerator, stay with me now)

3)... (n*(n+1)+2(n+1))/2 = (n^2+n+2n+2)/2 (oh wow, quadratics!, using quadratics in the numerator...

4)...(n^2+n+2n+2)/2= (n+1)*(n+2)/2 (oh wow, I think I see it!)....

5)...(n+1)*(n+2)/2 =((n+1)*((n+1)+1))/2 (yeah, I proved it!!!!!)

All good right?WRONG!!!

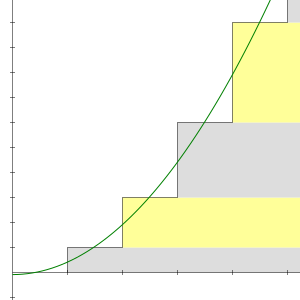

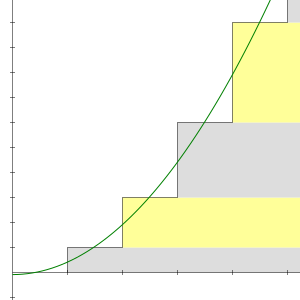

^^^This is the chart using cartesian coordinates for the above proof via induction. In fact, the summation formula proved via induction is DIVERGENT, it does not approach a finite limit, so in reality the induction proof is not true for the ENTIRE subset. This is what Godell is getting at. How the hell does infinity = infinity^2/2?

So again how is mathematical induction consistent AND complete proof?

Matter of fact, how can ANYTHING that involves an assumption as a foundation lead to consistent and complete proof at all? You don't see the irony in that? That's what Godell saw! If it wasn't true, you would never get error messages on your calculator. It does so because it has inherent limitations. So in fact, in science as well you must use faith to get by, because you can't REALLY prove everything to be true, you just know it is.

what you demonstrated here is misunderstanding in proof of by induction rather than a problem with the method. you can't assume 0+1+2+3+...= (n*(n+1))/2. when you do that you assume that your statement is true and there is noting left to prove.

Gödel was a convinced theist.[21] He held the notion that God was personal, which differed from the religious views of his friend Albert Einstein.

He believed firmly in an afterlife, stating: "Of course this supposes that there are many relationships which today's science and received wisdom haven't any inkling of. But I am convinced of this [the afterlife], independently of any theology." It is "possible today to perceive, by pure reasoning" that it "is entirely consistent with known facts." "If the world is rationally constructed and has meaning, then there must be such a thing [as an afterlife]."[22]

In an unmailed answer to a questionnaire, Gödel described his religion as "baptized Lutheran (but not member of any religious congregation). My belief is theistic, not pantheistic, following Leibniz rather than Spinoza."[23] Describing religion(s) in general, Gödel said: "Religions are, for the most part, bad—but religion is not".[24] About Islam he said: "I like Islam, it is a consistent [or consequential] idea of religion and open-minded.

let's have a look see at the basis of your great math, natural numbers. Well I can't believe it, these numbers ain't loyal!

let's have a look see at the basis of your great math, natural numbers. Well I can't believe it, these numbers ain't loyal!

No, that's wrong, you're mistaking assumption aka faith for science. That's why it's called "induction", and not "consistent and complete". You prove it's true for an element in the set you're using for your axiom. then you say, since it holds for element #1, let's assume it holds for element n. Induction ALWAYS involves that leap of faith. Using my example above, 0 = (0*(0+1))/2. so the statement is true for element 0. Then based on that, let's assume it's true for n,....and you know the rest. that's why the proof works but in reality the axiom is false over the entire subset of natural numbers. Most proofs involve assumptions aka faith at one point or another, it is blowing my mind that y'all not getting what Godell is saying. He is simply saying since most of your proofs outside of basic mathematical operations involve assumptions, ESPECIALLY in recursive sets/axioms, you can't consistently and completely prove the majority of what you state is true! Faith and science have become one!

yes and after you take that leap of faith the next step is to see whether it's true or not. you just don't stick with the leap of and say QED. and as far as your example i don't see how it disproves anything. if by the step where you claimed you proved it the right hand side is not equal to you the left hand side then you having proved anything if it is then they would hold for all natural numbers.

Is not the proof correct but the statement divergent using the set of all natural numbers? Is this in what you place your beliefs?

Is not the proof correct but the statement divergent using the set of all natural numbers? Is this in what you place your beliefs?

So does infinity = infinity^2/2?Is not the proof correct but the statement divergent using the set of all natural numbers? Is this in what you place your beliefs?

Again, please advise me the steps required to join the faith you call math Godell trolled y'all scientists and you not even realizing it

Godell trolled y'all scientists and you not even realizing it

@blackzeus do you know a lot about algorithm analysis? i may need your help with a proof i have to do for an assignment.

what statement is divergent and so what if it is. and what is infinity?

Self-referential = recursive, which is what I mentioned in my first post. The physical example I gave of an inverse hyperbola shows that it is supposed to trend towards 0 but that is something we ASSUME. You can't consistently and completely prove that at infinity x = 0 because THERE IS NO PHYSICAL QUANTIFICATION OF INFINITY. Infinity is a concept, not a numerical fact. That's the inherent limitation! Every time you use calculus or differential equations you ASSUME certain things to be true in order to solve your problem. Thus, in all but the most trivial axiomatic systems (e.g. addition), you can't consistently and completely prove everything, you have to make ASSUMPTIONS (e.g. limits). All recursive functions that trend towards a value most trend towards either infinity or 0. (using cartesian coordinate system) So we assume that eventually it reaches 0 or infinity in order to simplify our lives. We know it to be true becaue it works out in our calculations, but we can't consistently and completely prove it. Feel free to correct me if you feel I'm wrong.

What is mathematical induction? You have:

1) Base case. E.g. 0+1+2+3+...= (n*(n+1))/2

2) Induction step. Let's declare a set G(n) for all natural numbers. If G(n) is true, then G(n+1) is also true. Using quadratics you can prove that in fact it is also true for G(n+1) as follows:

(0+1+2+..)+(n+1)=((n+1)*((n+1)+1))/2

Now remember for induction we ASSUME (big key word, how in the f*ck is that not a leap of faith?!!) the base case is true, so assuming in fact 0+1+2+3+...= (n*(n+1))/2 is true, we get---->

1)...=(n*(n+1))/2 + (n+1) = ((n+1)*((n+1)+1))/2

2)...((n+1)*((n+1)+1))/2 = (n*(n+1)+(n+1)+(n+1))/2 = (n*(n+1)+2(n+1))/2 (I did that by multiplying the numerator, stay with me now)

3)... (n*(n+1)+2(n+1))/2 = (n^2+n+2n+2)/2 (oh wow, quadratics!, using quadratics in the numerator...

4)...(n^2+n+2n+2)/2= (n+1)*(n+2)/2 (oh wow, I think I see it!)....

5)...(n+1)*(n+2)/2 =((n+1)*((n+1)+1))/2 (yeah, I proved it!!!!!)

All good right?WRONG!!!

^^^This is the chart using cartesian coordinates for the above proof via induction. In fact, the summation formula proved via induction is DIVERGENT, it does not approach a finite limit, so in reality the induction proof is not true for the ENTIRE subset. This is what Godell is getting at. How the hell does infinity = infinity^2/2?

So again how is mathematical induction consistent AND complete proof?

Matter of fact, how can ANYTHING that involves an assumption as a foundation lead to consistent and complete proof at all? You don't see the irony in that? That's what Godell saw! If it wasn't true, you would never get error messages on your calculator. It does so because it has inherent limitations. So in fact, in science as well you must use faith to get by, because you can't REALLY prove everything to be true, you just know it is.

i've been saying this for years. but nobody listens. all that stuff about we know this we know that. we REALLLLY dont know nothing. WE ASSUME things based on the patters we can see currently and have seen in the past(once we were able to locate information of the past). some things that happened to far back where we have no written evidence of someone else counting. we have to ASSUME/Guess to some degree or take an educated guess. by stretching a pattern we do see today out to cover for what we dont see in history and in the future.1+1 is not consistent and complete? It relates more to computer programming:

E.g. N*(n-1) You have to prove both the negation and the statement for the theory to be consistent and complete. So for example if you say according to your theory from Set (0,infinity) N*(n-1) = 0, you have to prove it is both true for every element of the set, and that also the contrary is false. But you have to realize that in a lot of these theories in our reality you have to make an approximation, e.g. inverse hyperbola that approaches +/- infinity. Theoretically you assume that it approaches infinity, but in your lifetime you will never be able to prove that, there's too many elements to the set. You can't discount the fact that perhaps at infinity, N*(n1) is not equal to 0 until you can prove it. Basically a lot of sh*t is math is taken for granted, especially in recursive sets of elements, basically a function playing on itself. In short, even scientists operate on faith sometimes

i've been saying this for years. but nobody listens. all that stuff about we know this we know that. we REALLLLY dont know nothing. WE ASSUME things based on the patters we can see currently and have seen in the past(once we were able to locate information of the past). some things that happened to far back where we have no written evidence of someone else counting. we have to ASSUME/Guess to some degree or take an educated guess. by stretching a pattern we do see today out to cover for what we dont see in history and in the future.

basically Math is not an exact science. as black and white as math seems. its too many unknowns to know for sure of much of anything.

What's infinity to an ant is only 6' to us as a human. A lot of times in the midst of all our progress we lose perspective, and think we run the galaxy, Godell was like:

What's infinity to an ant is only 6' to us as a human. A lot of times in the midst of all our progress we lose perspective, and think we run the galaxy, Godell was like:

Please reread my post breh. You missed the point like the Chicago Bulls:

It's part of the point, because your misunderstanding of this seems to be bleeding into your other arguments. And I don't understand how further specifying the definition refutes my argument: You asked if "1+1" is consistent and complete and I simply responded that it is not an effectively generated theory capable of expressing elementary arithmetic. So applying Godel's Incompleteness Theorem to that makes no sense.I don't want to argue over definitions, but a statement is a subset of an axiom. E.g., if I say x+y = y+x, then 1+2 = 3 = 2+1 is a subset of that axiom, e.g. a mathematical relation that follows said axiom, but that's not the main point here IMHO

Again, "x = x" is not an effectively generated theory capable of expressing elementary arithmetic so Godel's Incompleteness Theorem does not apply.Godell's theorem is not true for all subsets of axiomatic theory, even if you want to choose natural numbers for example, when is x = x not consistently and completely true?

It only limits our human ability to conceptualize it but there are tons of mathematical facts like that. We don't go saying Euler's formula (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euler's_formula) is just a leap of faith because there's no physical quantification of imaginary numbers. There are some numbers that are easily expressed in base 10 that have infinitely long counterparts in base 2 and vice versa. That's just a limitation of the math tools we have and the way we perceive things.THERE IS NO PHYSICAL QUANTIFICATION OF INFINITY. Infinity is a concept, not a numerical fact. That's the inherent limitation!

Exactly, but the type of completeness issues we could possibly run into are not inherent in the usage of infinity. They are do to self-referential statements. E.g. "this statement is not provable" is true but not expressible in the system. This is the "Godel statement" that exists in all systems that makes Godel's theorem so amazing. I could trivial add an axiom that says "'This statement is not provable' is always true", but would that wouldn't deal with all the true statements that we can't express (i.e. incomplete) and it might lead to contradictions in other proofs (i.e. inconsistent). Note that this has nothing to do with your thoughts on infinity.Thus, in all but the most trivial axiomatic systems (e.g. addition), you can't consistently and completely prove everything

Godel's incompleteness theorem is not about "consistently and completely" proving a statement within a system. It is about an entire system not being able to be consistent, complete and effectively generated by a computer. These words, consistent and complete, have specific mathematical meanings that you seem to be mixing up with colloquial English meanings.All recursive functions that trend towards a value most trend towards either infinity or 0. (using cartesian coordinate system) So we assume that eventually it reaches 0 or infinity in order to simplify our lives. We know it to be true becaue it works out in our calculations, but we can't consistently and completely prove it. Feel free to correct me if you feel I'm wrong.

1) Why would you have to "assume" the base case is true when it already has its own separate, proof by induction? And if you assume anything is true then it is true and your solution has to be qualified with that assumption unless it's an implicit axiom of the system.What is mathematical induction? You have:

1) Base case. E.g. 0+1+2+3+...= (n*(n+1))/2

2) Induction step. Let's declare a set G(n) for all natural numbers. If G(n) is true, then G(n+1) is also true. Using quadratics you can prove that in fact it is also true for G(n+1) as follows:

....

i read it and i'm telling you it's gibberish. don't see what proving 0+1+2+3+...= (n*(n+1))/2 have to do with the summation being divergent. the whole point of the induction prove is to show that they are equal for all natural numbers. so even if infinity = n+1 or T that would still hold.

, no, once you plug in really large numbers its wrong, that's what the (x,y) plot shows. There is no end, it goes to infinity, so in essence:

, no, once you plug in really large numbers its wrong, that's what the (x,y) plot shows. There is no end, it goes to infinity, so in essence: And on top of it, you are decreasing the number you are adding by each time. That would be like you expecting 10+9+8+7+...=10^2, that's crazy talk. As the axiom approaches infinity, the math behind it becomes ludicrous. You believe it's true at infinity by faith, not by fact. That is Godell's point.

And on top of it, you are decreasing the number you are adding by each time. That would be like you expecting 10+9+8+7+...=10^2, that's crazy talk. As the axiom approaches infinity, the math behind it becomes ludicrous. You believe it's true at infinity by faith, not by fact. That is Godell's point.

It's part of the point, because your misunderstanding of this seems to be bleeding into your other arguments. And I don't understand how further specifying the definition refutes my argument: You asked if "1+1" is consistent and complete and I simply responded that it is not an effectively generated theory capable of expressing elementary arithmetic. So applying Godel's Incompleteness Theorem to that makes no sense.

Again, "x = x" is not an effectively generated theory capable of expressing elementary arithmetic so Godel's Incompleteness Theorem does not apply.

The first incompleteness theorem states that no consistent system of axioms whose theorems can be listed by an "effective procedure" (e.g., a computer program, but it could be any sort of algorithm) is capable of proving all truths about the relations of the natural numbers (arithmetic).

It only limits our human ability to conceptualize it but there are tons of mathematical facts like that. We don't go saying Euler's formula (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euler's_formula) is just a leap of faith because there's no physical quantification of imaginary numbers. There are some numbers that are easily expressed in base 10 that have infinitely long counterparts in base 2 and vice versa. That's just a limitation of the math tools we have and the way we perceive things.

Exactly, but the type of completeness issues we could possibly run into are not inherent in the usage of infinity. They are do to self-referential statements. E.g. "this statement is not provable" is true but not expressible in the system. This is the "Godel statement" that exists in all systems that makes Godel's theorem so amazing. I could trivial add an axiom that says "'This statement is not provable' is always true", but would that wouldn't deal with all the true statements that we can't express (i.e. incomplete) and it might lead to contradictions in other proofs (i.e. inconsistent). Note that this has nothing to do with your thoughts on infinity.

Godel's incompleteness theorem is not about "consistently and completely" proving a statement within a system. It is about an entire system not being able to be consistent, complete and effectively generated by a computer. These words, consistent and complete, have specific mathematical meanings that you seem to be mixing up with colloquial English meanings.

In classical deductive logic, a consistent theory is one that does not contain a contradiction.[1][2] The lack of contradiction can be defined in either semantic or syntactic terms. The semantic definition states that a theory is consistent if and only if it has a model, i.e. there exists an interpretation under which all formulas in the theory are true. This is the sense used in traditional Aristotelian logic, although in contemporary mathematical logic the term satisfiable is used instead. The syntactic definition states that a theory is consistent if and only if there is no formula P such that both P and its negation are provable from the axioms of the theory under its associated deductive system.

1) Why would you have to "assume" the base case is true when it already has its own separate, proof by induction? And if you assume anything is true then it is true and your solution has to be qualified with that assumption unless it's an implicit axiom of the system.

2) What exactly are you trying to prove? Are you trying to prove that the relation is true by making it the base case and assuming it's true?

Breh it's too late for this sh*t, I really don't want to go back and forth on basic sh*t. Proof by Induction = YOU PROVE IT'S TRUE FOR ONE ELEMENT, THEN ASSUME IT'S TRUE FOR THE ENTIRE SET OF N, THEN YOU PROVE VIA THE INDUCTION STEP IT'S TRUE FOR N+1. THE FLAW IS IN THE WHOLE SYSTEM OF PROOF BY INDUCTION, IT REQUIRES AN ASSUMPTION!!!!

Breh it's too late for this sh*t, I really don't want to go back and forth on basic sh*t. Proof by Induction = YOU PROVE IT'S TRUE FOR ONE ELEMENT, THEN ASSUME IT'S TRUE FOR THE ENTIRE SET OF N, THEN YOU PROVE VIA THE INDUCTION STEP IT'S TRUE FOR N+1. THE FLAW IS IN THE WHOLE SYSTEM OF PROOF BY INDUCTION, IT REQUIRES AN ASSUMPTION!!!!You're clearly a smart dude but you've missed the mark on this man.

Don't worry I am still a faithful member of the church of math

Don't worry I am still a faithful member of the church of math