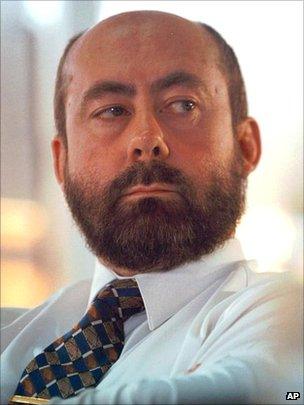

Meet the world’s most powerful doctor: Bill Gates

Some billionaires are satisfied with buying themselves an island. Bill Gates got a United Nations health agency in Geneva.

Over the past decade, the world’s richest man has become the World Health Organization’s second biggest donor, second only to the United States and just above the United Kingdom. This largesse gives him outsized influence over its agenda, one that could grow as the U.S. and the U.K. threaten to cut funding if the agency doesn’t make a better investment case.

[…]

However, his sway has NGOs and academics worried. Some health advocates fear that because the Gates Foundation’s money comes from investments in big business, it could serve as a Trojan horse for corporate interests to undermine WHO’s role in setting standards and shaping health policies.

Others simply fear the U.N. body relies too much on Gates’ money, and that the entrepreneur could one day change his mind and move it elsewhere.

Gates and his foundation team have heard the criticism, but they are convinced that the impact of their work and money is positive.

[…]

Strings attached

The Gates Foundation has pumped more than $2.4 billion into the WHO since 2000, as countries have grown reluctant to put more of their own money into the agency, especially after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Dues paid by member states now account for less than a quarter of WHO’s $4.5 billion biennial budget. The rest comes from what governments, Gates, other foundations and companies volunteer to chip in. Since these funds are usually earmarked for specific projects or diseases, WHO can’t freely decide how to use them.

Polio eradication is by far WHO’s best-funded program, with at least $6 billion allocated to it between 2013 and 2019, in great part because around 60 percent of the Gates Foundation’s contributions are earmarked for the cause. Gates wants tangible results, and wiping out a crippling disease like polio would be one.

But the focus on polio has effectively left WHO begging for funding for other programs, particularly to prop up poor countries’ health systems before the next epidemic hits.

The Ebola crisis of 2014, which killed 11,000 people in West Africa, was a particularly bruising experience for WHO. An emergency program

drawn up in the wake of the epidemic has so far received just around 60 percent of the $485 million needed for 2016-2017.