When is the last time superdelegates completely flipped on a candidate they initially supported?take off the super delegates. how many times do we have to say this. they have clouded your judgement. super delegates even being placed before the end is actually some nonsense no matter who you ride with. its used as an Optics narrative like i told yall earlier. its to scare off voters from voting for who they want if that person is not the one in the super lead(thanks to super delegates). but in reality they dont count til the end. The reason they dont count for either candidate til the end is due to the fact if all of a sudden the candidate in the lead falls off and the other candidate snatches the lead or ties it up and they go into the convention. The super deles will then have to truly decide who to back. especially if the original leader gets hawked and all of a sudden the actual voted on delegates are in their favor. super deles usually dont go against the people's vote. even shady Bill clinton admitted if sanders were to win out, he would flip his super delegate vote. that means a super dele vote isnt real until the end. STOP COUNTING THEM. Do not put them in the math again until the end. If you do, you are intentionally trying to have a misleading conversation.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Hillary Clinton’s Support Among Nonwhite Voters Has Collapsed

- Thread starter No1

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

More options

Who Replied?MrSinnister

Delete account when possible.

She's progressive on the usual shot White feminists usually are progressive on: whore enabling polices like abortion, and shot involving animals.and aside from the race baiting in 08, and her and her husband trying to jail every nucca in town. i aint that mad at her. She was born to a republican father. she repped for the repubs when she was a lot younger. she admitted after becoming a dem, that her time as a repub helped shape who she is today. what does that tell you? to the dem voters, stop fighting this. this is reality. she's progressive on a couple of fronts. and non of them have to do with economics, or war.

fukk @Darth Humanist for staying in his Australian feelings, like he knows shyt, because I said it. Dude don't know shyt about the White feminist game, daps 95% of my shyt, and negs me for speaking truth to it. You could just keep it moving and disagree brah

on everything you stand for, in your shyt conservative right country, thinking you know shyt.

on everything you stand for, in your shyt conservative right country, thinking you know shyt.i'll play along troll.That is far and away the dumbest thing you clueless, socialist, brain-dead people say. How about you put in your "fair share" of productivity? What is the rich's "fair share"? Is it an amount to give you some free handouts?

where's my money? i'm more productive today than i have ever been in the past. yet my ceo is getting more and more doe while i starve outchea.

VERY GOOD READ

Workers Wages Aren't Rising Even Though They're More Productive

One of the most frustrating parts of the sluggish recovery has been paltry wage gains for most workers. The stock market may be booming, corporate profits increasing, and home values rising, but middle and lower-class workers often don't truly feel the benefit of such improvements unless wages rise.

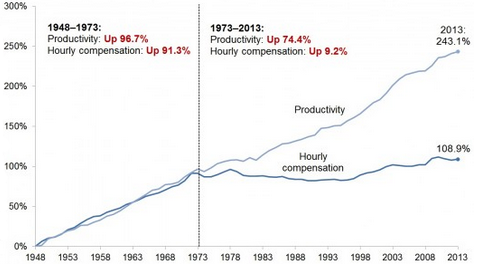

But wage stagnation isn't just a problem borne of the financial crisis. When you look at the relationship between worker wages and worker productivity, there's a significant and, many believe, problematic, gap that has arisen in the past several decades. Though productivity (defined as the output of goods and services per hours worked) grew by about 74 percent between 1973 and 2013, compensation for workers grew at a much slower rate of only 9 percent during the same time period, according to data from the Economic Policy Institute.

Productivity vs. Compensation

Economic Policy Institute

I spoke with Jan W. Rivkin, an economist and senior-associate dean for research at Harvard Business School who studies labor markets and U.S. competitiveness, in order to learn more about the history of the gap, and what it means for workers and the broader economy. The interview that follows has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Gillian White: So how long has the gap between wages and worker productivity persisted, and what does it mean for workers, other than the fact that they aren't seeing significant wage gains?

Jan Rivkin: From the end of WWII until the 1970s productivity in the U.S. and median wages grew in lockstep. But from the late 1970s until today we've seen a divergence, with productivity growing faster than wages. The divergence indicates that companies and the people who own and run them are doing much better than the people who work at the companies.

If the U.S. economy was healthy and competitive, we'd see firms able to do two things: win in the global marketplace and lift the living standards of the average American. Large businesses and the people who run them, and invest in them, are thriving but working and middle-class Americans are struggling—as are many small businesses.

Rivkin: There are a number of causes, one is the underlying shift in technology and globalization. Another is systematic underinvestment in the commons, which is a set of shared resources that every business needs in order to be productive: an educated populace, pools of skilled labor, a vibrant network of suppliers, strong infrastructure, basic R&D and so on. A third is shifts in institutions and politics and bargaining power, which is embodied in the decline in collective bargaining and the weakening of labor unions. There's no question that that is part of the story. How large a part? I don't think anyone has a well-informed perspective.

White: Ok, so let’s talk more about some of the principal reasons this gap developed and then started to widen.

Rivkin: Starting in the 1980s changes in geopolitics and technology opened the world for business. It became possible to do business from anywhere and to automate an increasing array of activities. Globalization and technological change brought great benefits to the U.S. economy, but it had a few other consequences.

i'll play along troll.

where's my money? i'm more productive today than i have ever been in the past. yet my ceo is getting more and more doe while i starve outchea.

He's the CEO and runs the company. He's more valuable than you, so what's your point? You're easily replaceable by the sound of it, he is not. Is YOUR productivity more important and have more of an impact than his on the company? Yes or no?

Is your productivity generating huge profits for your company?

The above aint enough for you trolls. so here's more

I got pretty pictures for yall lazy types. NO EXCUSES. IF YOU CAN'T SEE THE WRITING RIGHT IN YOUR FACE... we know you're a troll and nothing more. WE have one PIE for US and the Ballers club. We're all eating from the same pie. before it was more evenly distributed. you come up with a great idea you get paid well, you run a big company you get paid well, i work and produce a lot for said company, i get paid well. no one was crying about their ceo driving rolls royce's back then because the common man was cool with his brand new cadillac and pick up truck next to his house, yard, and white fence, with 2.5 kids and his wife.

now me and my 2.5 kids have to move into a 2 bedroom apt/condo. even if i say eff buying a home, i'll just rent. NOPE> thats a wrap too. my rent is 2200 for a 2 bed 1 bath today, 1 year from now they will raise it to 2400. up and up and up. i've seen these very comments in yelp under apartments. look for yourselves. people with pretty decent paying jobs are getting priced out of their apts because the rent keeps going up yet their wages are not following. yet the ceos are balling out of control. wall street is balling like never before. remember same pie. nothing has changed just that they have chnaged the rules to lock us out of our fair share.

Overworked America: 12 Charts That Will Make Your Blood Boil

Why "efficiency" and "productivity" really mean more profits for corporations and less sanity for you.

—By Dave Gilson

| July/August 2011 Issue

Want more rage? We've got 11 charts that show how the superrich spoil it for the rest of us.

In the past 20 years, the US economy has grown nearly 60 percent. This huge increase in productivity is partly due to automation, the internet, and other improvements in efficiency. But it's also the result of Americans working harder—often without a big boost to their bottom lines. Oh, and meanwhile, corporate profits are up 20 percent. (Also read our essay on the great speedup and harrowing first-person tales of overwork.)

YOU HAVE NOTHING TO LOSE BUT YOUR GAINS

Productivity has surged, but income and wages have stagnated for most Americans. If the median household income had kept pace with the economy since 1970, it would now be nearly $92,000, not $50,000.

GROWTH IS BACK...

...BUT JOBS AREN'T

SORRY, NOT HIRING

The sectors that have contributed the most to the country's overall economic growth have lagged when it comes to creating jobs.

THE WAGE FREEZE

Increase in real value of the minimum wage since 1990: 21%

Increase in cost of living since 1990:67%

One year's earnings at the minimum wage: $15,080

Income required for a single worker to have real economic security:$30,000

WORKING 9 TO 7

For Americans as a whole, the length of a typical workweek hasn't changed much in years. But for many middle-class workers, job obligations are creeping into free time and family time. For low-income workers, hours have declined due to a shrinking job market, causing underemployment.

LABOR PAINS

Median yearly earnings of:

Union workers: $47,684

Non-union workers: $37,284

DUDE, WHERE'S MY JOB?

More and more, US multinationals are laying off workers at home and hiring overseas.

PROUD TO BE AN AMERICAN

The US is part of a very small club of nations that don't require...

DIGITAL OVERTIME

A survey of employed email users finds:

22% are expected to respond to work email when they're not at work.

50% check work email on the weekends.

46% check work email on sick days.

34% check work email while on vacation.

I got pretty pictures for yall lazy types. NO EXCUSES. IF YOU CAN'T SEE THE WRITING RIGHT IN YOUR FACE... we know you're a troll and nothing more. WE have one PIE for US and the Ballers club. We're all eating from the same pie. before it was more evenly distributed. you come up with a great idea you get paid well, you run a big company you get paid well, i work and produce a lot for said company, i get paid well. no one was crying about their ceo driving rolls royce's back then because the common man was cool with his brand new cadillac and pick up truck next to his house, yard, and white fence, with 2.5 kids and his wife.

now me and my 2.5 kids have to move into a 2 bedroom apt/condo. even if i say eff buying a home, i'll just rent. NOPE> thats a wrap too. my rent is 2200 for a 2 bed 1 bath today, 1 year from now they will raise it to 2400. up and up and up. i've seen these very comments in yelp under apartments. look for yourselves. people with pretty decent paying jobs are getting priced out of their apts because the rent keeps going up yet their wages are not following. yet the ceos are balling out of control. wall street is balling like never before. remember same pie. nothing has changed just that they have chnaged the rules to lock us out of our fair share.

MrSinnister

Delete account when possible.

Why do they need corporate welfare if they're so valuable?He's the CEO and runs the company. He's more valuable than you, so what's your point? You're easily replaceable by the sound of it, he is not. Is YOUR productivity more important and have more of an impact than his on the company? Yes or no?

Is your productivity generating huge profits for your company?

Your charts don't answer the question. I'm not talking about the increase in CEO pay.

What is a "fair share"?

What is a "fair share"?

It was confusing as hell leading up to the caucus. They had like three different dates listed. I volunteered to be one of the people casting the official delegates for my precinct on May 1st.Washington does some weird congressional shyt afterward.

Why do they need corporate welfare if they're so valuable?

I've never said I agree with "corporate welfare". Now, the goals posts are being moved to "CEO's and corporations", when the original question had to do with asking what someones "fair share" is?

dont quote me until you read the article. and the post. i know you didnt read it all that fast and let it sink in. i dont care about him making a lot more than me? but 1000 times whati make? HELL NO.He's the CEO and runs the company. He's more valuable than you, so what's your point? You're easily replaceable by the sound of it, he is not. Is YOUR productivity more important and have more of an impact than his on the company? Yes or no?

Is your productivity generating huge profits for your company?

The only reason his company is doing so well is because people like me are more productive than ever. meaning I have just saved him the price of an extra person and extra benefits for said person. I'm doing that.

example: Where someone would take all day to setup their mailing labels. I can do that with a simple mail merge using word and outlook, pulling from my contacts. bam, done. i can automate it and make it do it on its on at a certain time of the day on certain days where the printer already knows when to hit it up. all i have to do is put the sticky labels in. wash, rinse , repeat. wait. i dont even need labels. i'll just email it out. mass email. saved the company money on postage, enveloples, etc. The CEO is not doing this. He asked me to do it. and i've done so well. that i can have 4 things going at once. because i'm that good with the tech. He isnt. he's a visionary that we need. i make his vision a reality for a lower cost than before since i'm so Ill with the tech of today. I DESERVE MORE MONEY. HE HAS IT. SO GIVE some of that back breh. he took TOO much out of the pie. its simple math. if every man, woman and child quite working for him, his great vision would die. i still have enough skill to get by day to day. Does he? great ideas mean nothing without people to implement them. unless you're a do it yourself type. some guys are. most ceos are not. Give me my money back.

Last edited:

dont quote me until you read the article. and the post. i know you didnt read it all that fast and let it sink in. i dont care about him making a lot more than me? but 1000 times whati make? HELL NO.

The only reason his company is doing so well is because people like me are more productive than ever. meaning I have just saved him the price of an extra person and extra benefits for said person. I'm doing that.

example: Where someone would take all day to setup their mailing labels. I can do that with a simple mail merge using word and outlook, pulling from my contacts. bam, done. i can automate it and make it do it on its on at a certain time of the day on certain days where the printer already knows when to hit it up. all i have to do is put the sticky labels in. wash, rinse , repeat. wait. i dont even need labels. i'll just email it out. mass email. saved the company money on postage, enveloples, etc. The CEO is not doing this. He asked me to do it. and i've done so well. that i can have 4 things going at once. because i'm that good with the tech. He isnt. he's a visionary that we need. i make his vision a reality for a lower cost than before since i'm so Ill with the tech of today. I DESERVE MORE MONEY. HE HAS IT. SO GIVE some of that back breh. he took TOO much out of the pie. its simple math. if every man, woman and child quite. his great vision would die. i still have enough skill to get by day to day. Does he? great ideas mean nothing without people to implement them. unless you're a do it yourself type. some guys are. most ceos are not. Give me my money back.

You're focusing on just the CEO, and I am not. You may very well put in more hours and work harder than many people that make more than you. I'm not going to argue that or dispute that as I don't know you. However, what is someones "fair share"? And, don't make the focus on just the CEO's and top executives.

This is ALL opinion. The OP used "revolutionary" because it was unprecedented and was called another adjective. It wasn't opinion. Your shyt is ALL opinion and I need you to figure out why, because you're chasing a false narrative.

da hell is unprecedented bout an white old man having some success in a primaries

shyt makes me think your a cac

shyt makes me think your a cacMrSinnister

Delete account when possible.

fukk all that, as it gets in the weeds quick when you try to set a far percentage. Corporations fukked the averages all up, starting in the 80's (coincidently when their tax liabilities started going down, and the workers started up in comparison), while workers, enabled by automation to work more efficiently, gained them far more revenue from added productivity.I've never said I agree with "corporate welfare". Now, the goals posts are being moved to "CEO's and corporations", when the original question had to do with asking what someones "fair share" is?

If you're not contributing to the economy, in a very arbitrary set manner, don't ask for any assistance. It's very difficult to set a percentage, because different business have different payroll needs.

fukk all that, as it gets in the weeds quick when you try to set a far percentage. Corporations fukked the averages all up, starting in the 80's (coincidently when their tax liabilities started going down, and the workers started up in comparison), while workers, enabled by automation to work more efficiently, gained them far more revenue from added productivity.

If you're not contributing to the economy, in a very arbitrary set manner, don't ask for any assistance. It's very difficult to set a percentage, because different business have different payroll needs.

I guess my question is, when you guys say "fair share", are you talking about the top .1%, top 1%, top 10%, top 20%, or what?

it's pretty simple. most everyone agrees with progressive taxationI guess my question is, when you guys say "fair share", are you talking about the top .1%, top 1%, top 10%, top 20%, or what?

Warren Buffett's secretary should not be paying a higher porportion of her income to taxes than him. These CEOs should not be paying less in taxes by percentage of their income than the workers making 1/1000th of them

once that is ironed out, the fair share question actually comes into play. where we stand it's meaningless posturing

- Status

- Not open for further replies.