Ornette Coleman, the alto saxophonist and composer who was one of the most powerful and contentious innovators in the history of jazz, died on Thursday morning in Manhattan. He was 85.

The cause was cardiac arrest, a representative of the family said.

Mr. Coleman widened the options in jazz and helped change its course. Partly through his example in the late 1950s and early ’60s, jazz became less beholden to the rules of harmony and rhythm, and gained more distance from the American songbook repertoire. His own music, then and later, became a new form of highly informed folk song: deceptively simple melodies for small groups with an intuitive, collective language, and a strategy for playing without preconceived chord sequences. In 2007, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his album “Sound Grammar.”

Continue reading the main story

Related Coverage

His early work — a kind of personal answer to his fellow alto saxophonist and innovator Charlie Parker — lay right within the jazz tradition and generated a handful of standards among jazz musicians of the last half-century. But he later challenged assumptions about jazz from top to bottom, bringing in his own ideas about instrumentation, process and technical expertise.

He was also more voluble and theoretical than John Coltrane, the other great pathbreaker of that era in jazz, and became known as a kind of musician-philosopher, with interests much wider than jazz alone; he was seen as a native avant-gardist and symbolized the American independent will as effectively as any artist of the last century.

Slight, Southern and soft-spoken, Mr. Coleman eventually became a visible part of New York cultural life, attending parties in bright satin suits; even when frail, he attracted attention. He could talk in nonspecific and sometimes baffling language about harmony and ontology; he became famous for utterances that were sometimes disarming in their freshness and clarity or that began to make sense about the 10th time you read them.

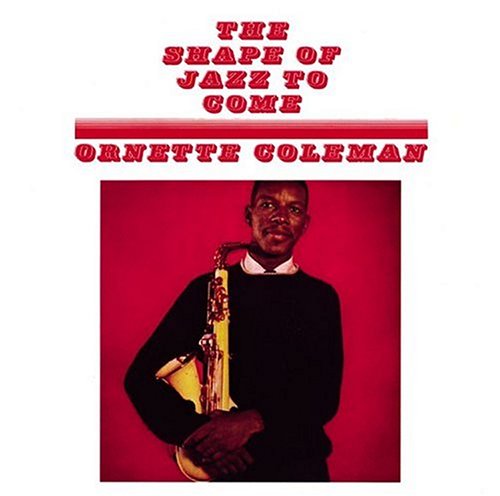

Yet his music was usually not so oblique. At best, it could be for everybody. Very few listeners today would need prompting to understand the appeal of his early songs like “Una Muy Bonita” (bright, bouncy) and “Lonely Woman” (tragic, flamencoesque). His run of records for Atlantic near the beginning of his career — especially “The Shape of Jazz to Come,” “Change of the Century” and “This Is Our Music” — pushed through skepticism, ridicule and condescension, as well as advocacy, to become recognized as some of the greatest albums in jazz history.

His composing voice, and his sense of band interplay, was intact by 1959, and this was the moment when he caught the ear of almost every important jazz musician in the world. He wrote short melody sketches, nearly always in a major key, which could sound like old children’s songs, and, in pieces like “Turnaround” and “When Will the Blues Leave?,” brilliant blues lines. With the crucial help of the trumpeter Don Cherry, he organized his band to act like separate hearts within a single organism.

Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman was born in Fort Worth on March 9, 1930, and lived in a house very near one of the many railroad tracks crisscrossing the area. According to various sources, his father, Randolph, who died when he was 7, was a construction worker and a cook, and his mother, Rosa, was a clerk in a funeral home; both, he liked to say, were born on Christmas Day. He attended I.M. Terrell High School — the same school that three of his future bandmates, the saxophonist Dewey Redman and the drummers Charles Moffett and Ronald Shannon Jackson, would later graduate from. Other graduates from the same school included the saxophonists King Curtis, Prince Lasha and Julius Hemphill; the clarinetist John Carter; and Red Connor, a bebop tenor saxophonist with no discographical trail who, Mr. Coleman often said, influenced him by playing jazz as “an idea,” rather than as a series of patterns.

Mr. Coleman’s melodies may be easy to appreciate, but his sense of harmony has been a complicated issue from the start. He has said that when he first learned to play the saxophone — his mother gave him an alto saxophone when he was around 14 — he didn’t understand that because of transposition between instruments, a C in the piano’s “concert key” was an A on his instrument. (He also seems to have believed that when he was reading CDEFGAB, a C-major scale, he was playing the notes ABCDEFG.) When he found out the truth, a lifelong suspicion of the rules of Western harmony and musical notation began.

In essence, Mr. Coleman believed that all people had their own tonal centers, and that “unison” — a word he often used, though not always in its normal musical-theory sense — was a group of people playing together harmoniously, even if in different keys.

“I’ve learned that everyone has their own moveable C,” he said to the writer Michael Jarrett in an interview published in 1995; he identified it as “Do,” the nontempered start of anyone singing or playing a “do-re-mi” major-scale sequence. During the same conversation, he remarked that he always wanted musicians to play with him “on a multiple level.”

“I don’t want them to follow me,” he explained. “I want them to follow themselves, but to be with me.”

Full article :

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/12/a...man-jazz-saxophonist-dies-at-85-obituary.html

is everyone dieing today

is everyone dieing today to one of the best saxes ever. He always put it down.

to one of the best saxes ever. He always put it down.