Yes. Due to the history of this country. They were started by the Freedman's Bureau. It's not like they were like hey -- name our schools after white folks!

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCU), institutions of

higher education in the United States founded prior to 1964 for

African American students. The term was created by the Higher Education Act of 1965, which expanded federal funding for colleges and universities.

The first HBCUs were founded in Pennsylvania and Ohio before the

American Civil War (1861–65) with the purpose of providing black youths—who were largely prevented, due to racial

discrimination, from attending established colleges and universities—with a basic education and training to become teachers or tradesmen. The Institute for Colored Youth (briefly the African Institute at its founding) opened on a farm outside Philadelphia in 1837. It is today

Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, which is part of the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education. The Ashmun Institute, also located near Philadelphia, provided theological training as well as basic education from its founding in 1854. It became

Lincoln University in 1866 in honour of U.S. Pres.

Abraham Lincoln and was private until 1972. The oldest private HBCU in the U.S. was founded in 1856, when the Methodist Episcopal Church opened

Wilberforce University in Tawawa Springs (present-day Wilberforce), Ohio, as a coeducational institution for blacks who had escaped slavery in the South through the

Underground Railroad. It closed in 1862 but reincorporated in 1863 under the

auspices of the

African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), a historically African American

Methodist denomination.

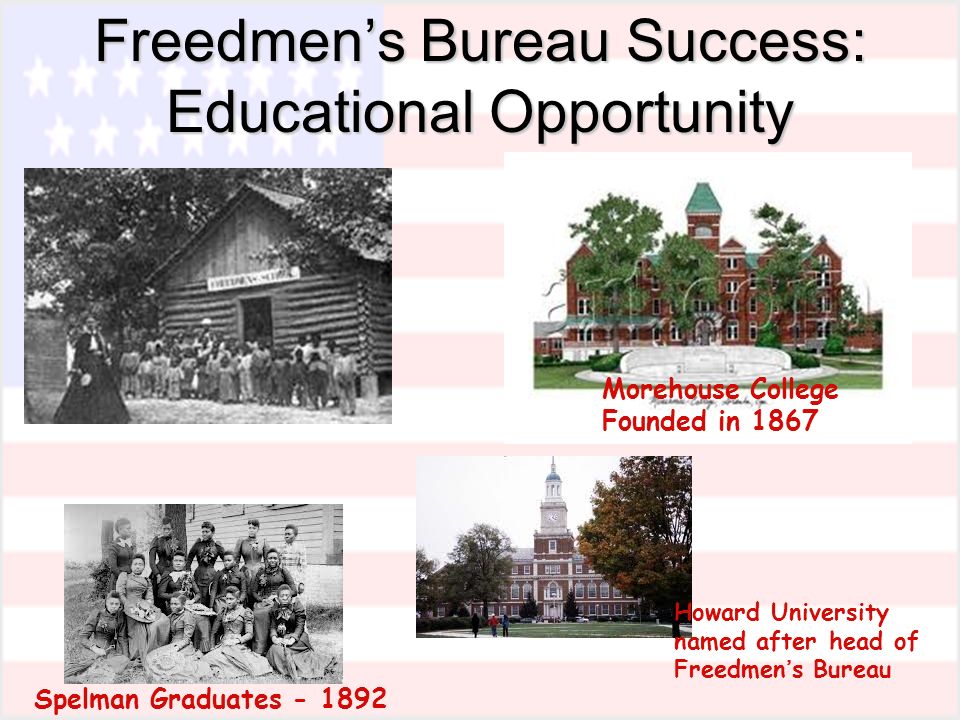

F

ollowing the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, HBCUs were founded throughout the South with support from the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal organization that operated during Reconstruction to help former slaves adjust to freedom. Such institutions as Atlanta University (1865; now Clark Atlanta University), Howard University, and Morehouse College (1867; originally the Augusta Institute) provided a liberal arts education and trained students for careers as teachers or ministers and missionaries, while others focused on preparing students for industrial or agricultural occupations. Some institutions, such as Morehouse, were all-male schools. Others, such as Spelman College(1924; originally founded in 1881 as Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary), were all-female. Most, however, were coeducational.

The growth of HBCUs spurred controversy among prominent African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some critics noted that many HBCUs, particularly those existing in the years immediately following the Civil War, were founded by whites, many of whom had negative preconceptions of the social, cultural, and

intellectual capabilities of blacks. As blacks were generally barred, particularly in the South, from established institutions, critics questioned whether separate schools in fact hindered efforts toward social and economic equality with whites.

Another issue was whether vocational training or a more classically “intellectual” education would best serve the interests of African Americans.

Booker T. Washington, an

exemplary supporter of vocational training, founded the Tuskegee Institute (1881; now

Tuskegee University), which emphasized agricultural and industrial education. Like the Hampton Normal and Industrial Institute (1868; now

Hampton University), Tuskegee served as a model for several subsequent HBCUs that organized under an 1890

amendment to the

Land-Grant College Act of 1862 that promoted the creation of African American

land-grant colleges. The most prominent exponent of an intellectual approach was the

Harvard University-trained sociologist

W.E.B. Du Bois, who argued for the necessity of

cultivating a “talented tenth” of well-educated

community leaders. Even as this debate continued, the institutionalization of

racial segregation both within and outside the South made it even more difficult for black students to study anywhere other than in HBCUs until the desegregation efforts of the mid-20th century.

In the early 21st century there were more than 100 HBCUs in the United States, predominantly in the South. While some were two-year schools, many offered four years of study. Some maintained a vocational focus, while others had developed into major research institutions. Also, while several HBCUs continued to have predominantly African American student bodies, others no longer did.