Lakota elders helped a white man preserve their language. Then he tried to sell it back to them.

“No matter how it was collected, where it was collected, when it was collected, our language belongs to us," said Ray Taken Alive, a Lakota teacher.

“No matter how it was collected, where it was collected, when it was collected, our language belongs to us," said Ray Taken Alive, a Lakota teacher.

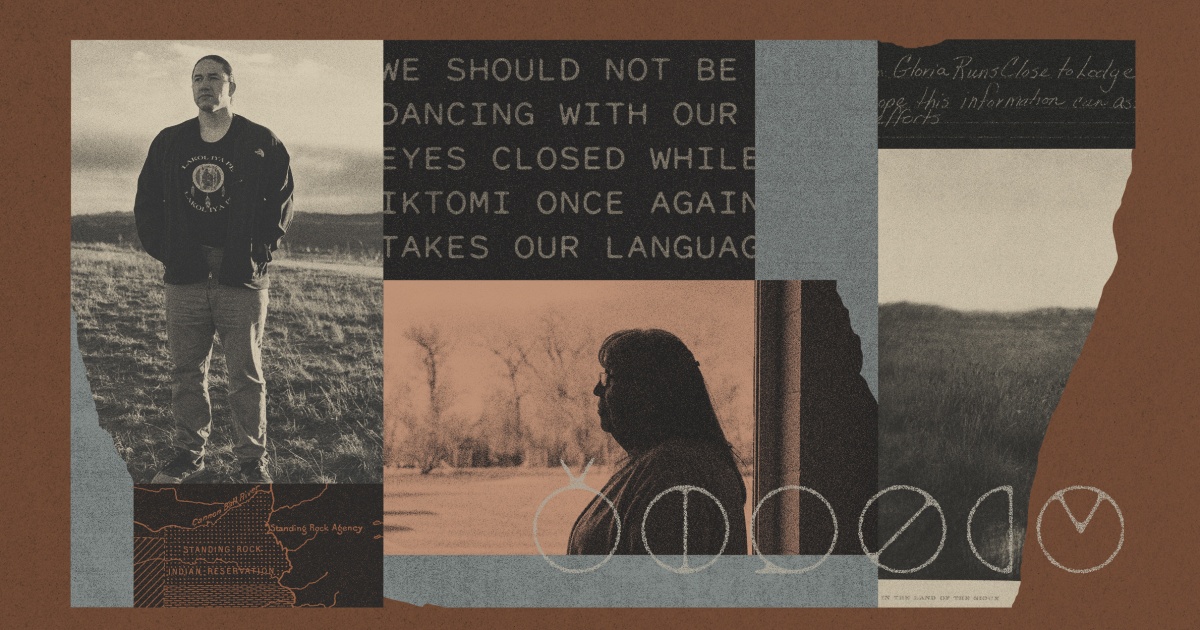

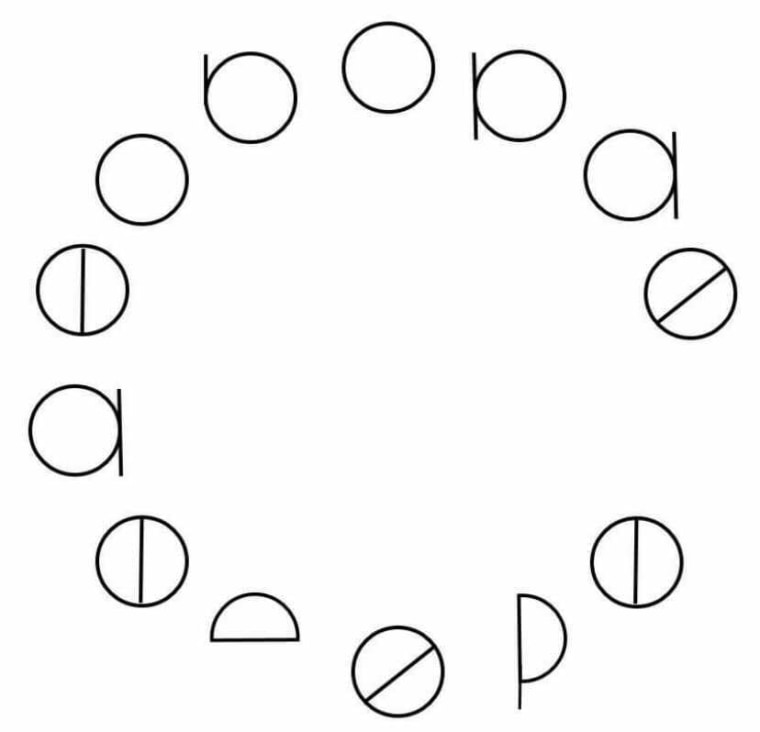

Ray Taken Alive and Gloria Runs Close To Lodge-Goggles have both accused the founder of The Language Conservancy of taking their family’s data for his work.J.D. Reeves for NBC News / Tara Rose Weston / Natalie Behring

June 3, 2022, 7:00 AM EDT / Updated June 3, 2022, 4:08 PM EDT

By Graham Lee Brewer

STANDING ROCK INDIAN RESERVATION, S.D. — Ray Taken Alive had been fighting for this moment for two years: At his urging, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council was about to take the rare and severe step of banishing a nonprofit organization from the tribe’s land.

The Lakota Language Consortium had promised to preserve the tribe’s native language and had spent years gathering recordings of elders, including Taken Alive’s grandmother, to create a new, standardized Lakota dictionary and textbooks.

But when Taken Alive, 35, asked for copies, he was shocked to learn that the consortium, run by a white man, had copyrighted the language materials, which were based on generations of Lakota tradition. The traditional knowledge gathered from the tribe was now being sold back to it in the form of textbooks.

“No matter how it was collected, where it was collected, when it was collected, our language belongs to us. Our stories belong to us. Our songs belong to us,” Taken Alive, who teaches Lakota to elementary school students, told the tribal council in April.

On May 3, the tribal council voted nearly unanimously to banish the Lakota Language Consortium — along with its co-founder Wilhelm Meya and its head linguist, Jan Ullrich — from setting foot on the reservation. What the council took into consideration wasn’t just the organization’s dealings with the Standing Rock Sioux; it turned out at least three other tribes had also raised concerns about Meya, saying he broke agreements over how to use recordings, language materials and historical records, or used them without permission.

Meya denies this. A spokesman shared letters of support for Meya’s work from five tribes and tribal schools, though in recent interviews and statements to NBC News, officials with four of those tribes said they had concerns about Meya’s methods.

Native Americans have been mined for financial benefit and academic accolades for centuries. Information collected on Native Americans has rarely been taken with their consent or been used to serve their communities, whether through research done on Indigenous remains robbed from gravesites or on blood samples used without permission. Still, there are Lakota people who support what the consortium is doing: They say preserving the endangered language is paramount.

This work has been lucrative for Meya, who started the Lakota Language Consortium in Indiana in the early 2000s. He’s also the CEO of The Language Conservancy, a nonprofit organization he founded soon afterward that works to revitalize other Indigenous languages.

In tax filings for 2020, Meya reported an annual salary of about $210,000 from his two nonprofit groups, according to tax disclosure documents. That kind of money bothers some in the Native American communities he’s worked in; on the Standing Rock reservation, the median income is just over $40,000.

Meya’s organizations have received more than $3.5 million in federal grants over the past 15 years for language revitalization projects with tribes across the country, records show. The Department of Health and Human Services alone has paid the Lakota Language Consortium nearly $1 million to create some of the textbooks the organization sells for $40 to $50 apiece.

Meya says his work is a vital tool in preserving the Lakota language, which did not previously have a standardized written form. He estimated that there are fewer than 1,500 fluent Lakota speakers left and that over the last decade and a half, the organization has helped add 50 to 100 more.

“Just because money is involved in it does not inherently make it an evil thing,” Meya said in a recent interview with NBC News. Most of the products his organizations make are free, he said, but the cost of printing textbooks has to come from somewhere. “That tends to be sometimes part of the rhetoric, ‘Oh, there’s money involved. It must be, you know, part of the overall colonization effort.’ Well, you know, that’s just not realistic.”

But several Indigenous academics, legal experts and tribal leaders say the consortium is asserting control over more than the teaching materials it makes; it’s the community-specific information and tribal history that’s contained within the books. Some of the words and phrases in the consortium’s materials have never been recorded or transcribed before, and charging a marginalized community any fee for them is unethical, the experts said.

Taken Alive and a growing number of tribal citizens believe all the dictionaries, textbooks and recordings should be free and accessible to the Indigenous communities that created the languages the products teach.

The conflict is part of a bigger dispute over how to preserve Native American languages and oral histories and whether outsiders should be allowed to make money off of this work.

Estimates vary, but there are slightly more than 100 Native American languages still spoken today, less than half of what existed before European colonization began. Whether through the destructive violence of Manifest Destiny or the assimilation efforts of the Indian boarding school era, the U.S. campaign to eliminate Native American languages has been highly effective. Most of those that remain are in danger of extinction. Many tribes, especially smaller ones with fewer resources, rely on non-Native organizations to preserve their languages.

A common trait of Native American cultures is to hold things like land, resources and knowledge communally. That runs into conflict with U.S. copyright laws, which allow companies and nonprofit organizations to commoditize their work product — including pieces of a shared language.

The Lakota Language Consortium notes on its website that “no one can copyright a language,” and the consortium says it shares its materials with those who ask to make copies for educational purposes. But the copyright on the materials still gives the organization control over how the information is used, which is what some tribal leaders find objectionable.

Even if a tribal nation has intellectual property laws protecting its cultural information, if it lacks the legal staff to assert control over that data, legal experts say it can still be vulnerable.

The debate over how information collected from tribes is handled has caught the attention of tribal citizens across the about half-dozen reservations where Lakota is a first language. The controversy has spilled into tribal politics and social media, igniting a fierce debate over identity, decolonization and tribal sovereignty.

Tribes in this situation are typically at a disadvantage, said Jane Anderson, an associate professor of anthropology and a legal scholar at New York University. Not only do tribes rarely share in the profits of language preservation efforts, they often have to pay part of the costs to implement them and have to purchase the end product, she said.

“There is something deeply unethical and inequitable in relation to that, and I hear it all the time across Indian Country,” she said.

Makalika Naholowa‘a, a Native Hawaiian attorney and the executive director at the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, said when organizations that trade in Indigenous data don’t freely share that information with the communities they gather it from, they are akin to miners or loggers, taking a valuable resource and selling it to whoever wants it.

“Data is the new oil,” she said.

Words passed down for generations

Ray Taken Alive started learning Lakota as a kid by listening to his grandmother Delores Taken Alive, who was a first-language speaker. She grew up in South Dakota, where her family had lived since long before their land was part of the United States. Delores was proud to have been given her Lakota name, Hiŋháŋ Sná Wiŋ, or Rattling Owl Woman, by her great-grandmother, who survived the massacre at Wounded Knee.As a child, when Delores was drifting off to sleep, she listened to her parents and grandparents tell stories in Lakota, and that’s how she learned the history of her people.

With the number of Lakota first-language speakers dwindling, Delores was eager to help preserve and transmit the language. Beginning in 2005, she recorded words and stories for Jan Ullrich, the linguist, and reviewed new entries in the Lakota Language Consortium’s dictionary. She signed an agreement with the consortium that paid elders up to $50 per hour, in exchange for exclusive rights to publish what they shared.

damn that's cold

damn that's cold