88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

Moving from a prison cell to a voting booth

By Jessica LussenhopBBC News Magazine

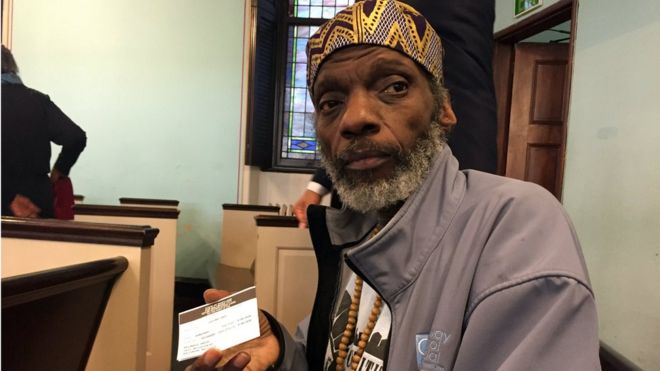

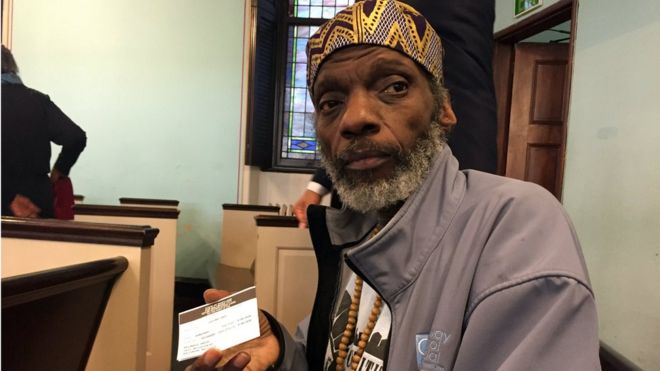

Image captionReginald Smith holds his newly obtained voter identification card

Erasing me

As restrictions on voting for former prison inmates are relaxed across the country, a new bloc of voters is emerging in the US.

Two weeks before primary day in Maryland, a unique campaign event - perhaps even a first in the country - took place in Baltimore: an "Ex-Offender Mayoral Candidate Forum".

Roughly 100 people sat in the sanctuary of a large church and waited to hear what seven candidates for Baltimore mayor planned to do to help the formerly incarcerated residents of the troubled city. The attendees came dressed in work uniforms, carrying small children and, in Reginald Smith's case, with his brand new voter registration card still tucked in its envelope.

"Dun-da-da," he sang, pulling the card out of a file filed with information about the election. "It's been so long since I voted - this is, like, for real new."

Smith, who was released in 2012 and is on parole until 2019, was among the very first to register to vote when it became legal for former inmates like him to do so in Maryland on March 10. After a hard fought battle by community activists, the Maryland legislature overrode the veto of Republican Governor Larry Hogan and restored the voting rights of 40,000 former inmates in February. An estimated 20,000 of those live in Baltimore.

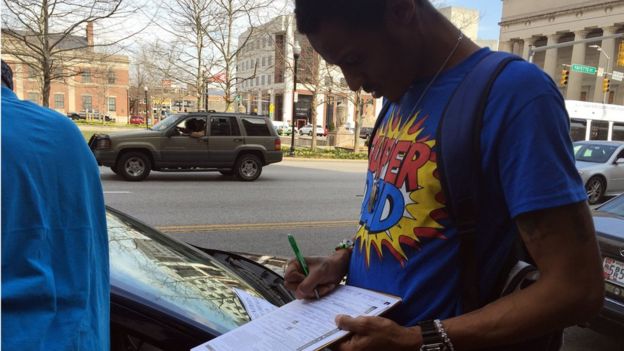

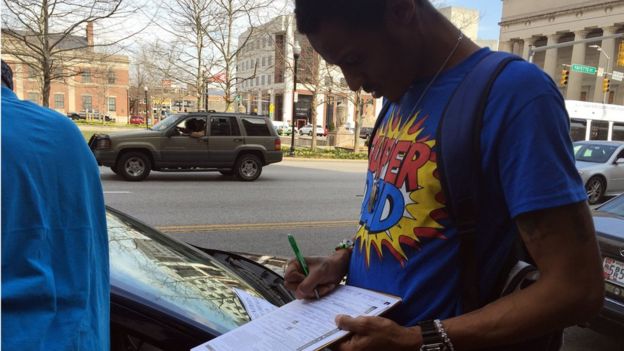

Image captionMarcus Dulin, who served three and a half years in prison, registers to vote

The US is far more restrictive of voting for former inmates than other developed nations, particularly for those who have been convicted of a felony, a term for more serious crimes that typically comes with a prison sentence of a year or longer. Maryland is the 14th state to allow former prisoners to vote as soon as they are released, regardless of additional probation or parole time. On Friday, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe announced that he is restoring the rights of 200,000 men and women with felony records by executive order, which could have huge implications for the swing state going into the elections in November. Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, says these kinds of restrictions on voting have been relaxed in 23 states so far.

"The trend is very much toward reform, but at the same time the sheer numbers in the justice system, the fact that the category of the disenfranchised is so broad means the impact is still very substantial," he says.

Laws that took away the right to vote from convicted criminals trace their roots back to the end of the Civil War and Reconstruction, and some were an overt effort to take rights away from newly freed African Americans. As US prisons filled with a disproportionate number of minorities, the racial impact of these laws was perpetuated.

"Because of the over-representation of communities of colour in the criminal justice system, this disenfranchisement dilutes the African-American vote in very serious ways," says Chris Uggen, a professor of sociology and law at the University of Minnesota.

An estimated 5.85 million people in the US are unable to vote because of their criminal records.

Uggen says turnout from this population is expected to be low, even as voting restrictions ease, but it is still a bloc that can have an impact on closely contested races.

Image captionJohn Comer and Perry Hopkins, centre, at city hall on the first day of legal registration for ex-offenders

Baltimore's mayoral race is just such an election. After the death of Freddie Gray one year ago, the city was gripped in civil unrest and Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake announced that she would not seek re-election. Her decision created a crowded field of candidates. Frontrunners include former Mayor Sheila Dixon and state Senator Catherine Pugh. Trailing them is businessman David Warnock and lawyer Elizabeth Embry, as well as reform-minded newcomers like activist DeRay Mckesson, who is well known nationally for his activism but doing poorly in local polls.

Communities United, which was instrumental in the political campaign to get the laws changed along with other civil rights organisations, turned the momentum from their victory in the legislature into a registration effort, setting up tables in some of Baltimore's poorest, most political inactive neighbourhoods. They spent much of last week shuttling ex-offenders to early voting for free in large white vans.

"Ex-offenders must vote!" read posters distributed by the group. "They are counting on us not to."

By the day of the mayoral forum, Communities United estimated something like 1,200 ex-offenders registered to vote in the April 26 primary.

"We are building an ex-felon movement. This is not just about the votes," says Perry Hopkins, a field organiser with the group and also a former inmate who cast his first vote on Thursday. "We believe we got enough votes to swing this election."

Image captionCandidates for Baltimore mayor address the formerly incarcerated attendees, including front runner Cathering Pugh (in green), DeRay Mckesson (in the vest) and Elizabeth Embry (in white)

Not long after the ex-offender candidate forum began, it was clear that emotions were running high. Candidates earned applause for supporting a $15 minimum wage and work options for recovering drug addicts, and loud condemnation when some departed early for other campaign events.

"If they leave, don't vote for them!" someone called.

And then there was a moment when former Baltimore mayor Dixon - who was forced to resign from office after being convicted of embezzlement - spoke in a somewhat detached tone about her brother's experience with the criminal justice system instead of her own. A murmur rippled through the crowd.

"Ain't you an ex-offender?" someone from the front pews called.

"No, I'm not an ex-offender," she answered, sounding peeved. "Mine was a misdemeanour."

The crowd jeered, audience members shook their heads in disbelief.

John Comer, co-director of Communities United, said the emotional tension was no surprise to him.

"This wasn't just a political forum. In many ways, it was a purge to get pain out ... people feel like they never had a voice."

"These people are still being punished by not being able to get a job, by not being able to get housing because of their criminal record, so now hopefully because they have the ability to vote we can organise people to come together and build power that way," he continued. "We pulled of something that just may be historic. Hopefully it can continue here and in other places as well. This is just the beginning."

Moving from a prison cell to a voting booth - BBC News

By Jessica LussenhopBBC News Magazine

- 25 April 2016

- From the sectionUS & Canada

Image captionReginald Smith holds his newly obtained voter identification card

Erasing me

As restrictions on voting for former prison inmates are relaxed across the country, a new bloc of voters is emerging in the US.

Two weeks before primary day in Maryland, a unique campaign event - perhaps even a first in the country - took place in Baltimore: an "Ex-Offender Mayoral Candidate Forum".

Roughly 100 people sat in the sanctuary of a large church and waited to hear what seven candidates for Baltimore mayor planned to do to help the formerly incarcerated residents of the troubled city. The attendees came dressed in work uniforms, carrying small children and, in Reginald Smith's case, with his brand new voter registration card still tucked in its envelope.

"Dun-da-da," he sang, pulling the card out of a file filed with information about the election. "It's been so long since I voted - this is, like, for real new."

Smith, who was released in 2012 and is on parole until 2019, was among the very first to register to vote when it became legal for former inmates like him to do so in Maryland on March 10. After a hard fought battle by community activists, the Maryland legislature overrode the veto of Republican Governor Larry Hogan and restored the voting rights of 40,000 former inmates in February. An estimated 20,000 of those live in Baltimore.

Image captionMarcus Dulin, who served three and a half years in prison, registers to vote

The US is far more restrictive of voting for former inmates than other developed nations, particularly for those who have been convicted of a felony, a term for more serious crimes that typically comes with a prison sentence of a year or longer. Maryland is the 14th state to allow former prisoners to vote as soon as they are released, regardless of additional probation or parole time. On Friday, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe announced that he is restoring the rights of 200,000 men and women with felony records by executive order, which could have huge implications for the swing state going into the elections in November. Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, says these kinds of restrictions on voting have been relaxed in 23 states so far.

"The trend is very much toward reform, but at the same time the sheer numbers in the justice system, the fact that the category of the disenfranchised is so broad means the impact is still very substantial," he says.

Laws that took away the right to vote from convicted criminals trace their roots back to the end of the Civil War and Reconstruction, and some were an overt effort to take rights away from newly freed African Americans. As US prisons filled with a disproportionate number of minorities, the racial impact of these laws was perpetuated.

"Because of the over-representation of communities of colour in the criminal justice system, this disenfranchisement dilutes the African-American vote in very serious ways," says Chris Uggen, a professor of sociology and law at the University of Minnesota.

An estimated 5.85 million people in the US are unable to vote because of their criminal records.

Uggen says turnout from this population is expected to be low, even as voting restrictions ease, but it is still a bloc that can have an impact on closely contested races.

Image captionJohn Comer and Perry Hopkins, centre, at city hall on the first day of legal registration for ex-offenders

Baltimore's mayoral race is just such an election. After the death of Freddie Gray one year ago, the city was gripped in civil unrest and Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake announced that she would not seek re-election. Her decision created a crowded field of candidates. Frontrunners include former Mayor Sheila Dixon and state Senator Catherine Pugh. Trailing them is businessman David Warnock and lawyer Elizabeth Embry, as well as reform-minded newcomers like activist DeRay Mckesson, who is well known nationally for his activism but doing poorly in local polls.

Communities United, which was instrumental in the political campaign to get the laws changed along with other civil rights organisations, turned the momentum from their victory in the legislature into a registration effort, setting up tables in some of Baltimore's poorest, most political inactive neighbourhoods. They spent much of last week shuttling ex-offenders to early voting for free in large white vans.

"Ex-offenders must vote!" read posters distributed by the group. "They are counting on us not to."

By the day of the mayoral forum, Communities United estimated something like 1,200 ex-offenders registered to vote in the April 26 primary.

"We are building an ex-felon movement. This is not just about the votes," says Perry Hopkins, a field organiser with the group and also a former inmate who cast his first vote on Thursday. "We believe we got enough votes to swing this election."

Image captionCandidates for Baltimore mayor address the formerly incarcerated attendees, including front runner Cathering Pugh (in green), DeRay Mckesson (in the vest) and Elizabeth Embry (in white)

Not long after the ex-offender candidate forum began, it was clear that emotions were running high. Candidates earned applause for supporting a $15 minimum wage and work options for recovering drug addicts, and loud condemnation when some departed early for other campaign events.

"If they leave, don't vote for them!" someone called.

And then there was a moment when former Baltimore mayor Dixon - who was forced to resign from office after being convicted of embezzlement - spoke in a somewhat detached tone about her brother's experience with the criminal justice system instead of her own. A murmur rippled through the crowd.

"Ain't you an ex-offender?" someone from the front pews called.

"No, I'm not an ex-offender," she answered, sounding peeved. "Mine was a misdemeanour."

The crowd jeered, audience members shook their heads in disbelief.

John Comer, co-director of Communities United, said the emotional tension was no surprise to him.

"This wasn't just a political forum. In many ways, it was a purge to get pain out ... people feel like they never had a voice."

"These people are still being punished by not being able to get a job, by not being able to get housing because of their criminal record, so now hopefully because they have the ability to vote we can organise people to come together and build power that way," he continued. "We pulled of something that just may be historic. Hopefully it can continue here and in other places as well. This is just the beginning."

Moving from a prison cell to a voting booth - BBC News