I'll start it off with someone alot of people don't know about in A.G Gaston. Happy Black History Month

By the 1960s, Arthur G. Gaston was probably the richest black man in America. He was the leading employer of blacks in Alabama and directly and indirectly gave substantial aid and comfort to the civil rights movement. In the decade after the Montgomery bus boycott, Martin Luther King Jr. and his allies used the A. G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham, Alabama, as a safe refuge to plan their activities. When Eugene “Bull” Connor, the notorious commissioner of public safety, had King arrested in 1963, Gaston put up the $160,000 bail money from his own pocket.

Despite these contributions, Gaston’s name does not appear in three main survey texts of black history: Darlene Clark Hines’s The African-American Odyssey (Upper Saddle River, N. J.: Prentice Hall, 2005); Joe William Trotter Jr.’s The African-American Experience (New York: Houghton-Mifflin, 2000); and John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994). All three compound their neglect by failing to mention other leading black entrepreneurs, such as the remarkable S. B. Fuller, Gaston’s main business rival during the 1950s and 1960s.

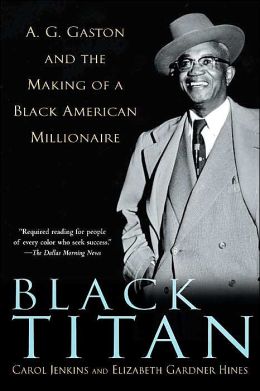

In writing Black Titan, a full-length biography, Carol Jenkins (Gaston’s niece) and Elizabeth Gardner Hines (his grandniece) have taken an important step toward making up for these omissions. Moreover, they show how Gaston was both a product of and a direct participant in a long tradition of black engagement in business, self-help, and mutual aid.

Born in 1893, Gaston grew up in poverty in the small town of Demopolis, Alabama. He was the son of a manual railroad worker and a cook for a prominent white family. When he was a teenager, the entire family moved to the booming industrial city of Birmingham, Alabama. His mother went to work for A. B. Loveman, a wealthy Jewish department store owner.

As is true for most entrepreneurs, Gaston’s rise up the economic ladder can be traced to a combination of luck and pluck. The connection to the Loveman family nurtured a favorable environment for a future business career. Loveman stood out as a model of how to prosper through long hours of hard work and careful attention to investments. The philanthropies of his wife, Minnie Loveman, were instrumental in Gaston’s decision to enroll as a student at the Tuggle Institute.

The institute’s organizational founder and chief sponsor was the Order of Calanthe, the women’s auxiliary of the Colored Knights of Pythias. Among black fraternal societies, the Knights represented a major force for mutual aid and social mobilization in the decades after the Civil War. The Tuggle Institute closely followed Booker T. Washington’s teaching methods of “industrial education” in the skilled trades and business. The Wizard of Tuskegee often visited the campus to deliver speeches of encouragement. From then on, Gaston was an enthusiastic disciple. Washington’s autobiography Up from Slavery was the first book he owned. Gaston’s favorite passage stated that “[e]very persecuted individual and race should get much consolation out of the great human law, which is universal and eternal, that merit, no matter under what skin found, is in the long run recognized and rewarded.... [T]he Negro ... should make himself, through skill, intelligence, and character, of such undeniable value to the community in which he lived that the community could not dispense with his presence” (qtd. on p. 41).

Although A. B. Loveman’s example and the education received at the Tuggle Institute helped to propel Gaston forward, it took many years for him to make significant headway. He fortunately took note of the trials and errors of earlier black businessmen in Birmingham, such as the bankers Charles M. “Boss” Harris and William Pettiford.

After serving in World War I, Gaston drove a delivery truck for a white-owned dry-cleaning company and, at perhaps the lowest point of his life, toiled as a coal miner. He was always alert to any opportunity to better his condition, though, no matter how modest. He tried out an idea to turn a profit by selling boxed lunches prepared by his mother to his fellow miners. It was such a success that he started to sell popcorn and peanuts on the side. Gaston saved an amazing two-thirds of his combined income at this time. Once he had enough money in hand, he took on the informal role of banker, extending loans at 25 percent interest to his coworkers.

Soon Gaston quit mining to set up the Booker T. Washington Burial Society, originally modeled after a fraternal order. It prospered in great part because of his carefully crafted alliance with black ministers who steered business to it from their congregations. He attracted still more customers by sponsoring gospel singers as well as Alabama’s “first regular Negro radio program” (p. 99).

Gaston was a pioneer among black entrepreneurs in the aggressive use of vertical integration. He began with insurance but moved on to control other parts of the process, such as undertaking and casket manufacturing. He also purchased a cemetery. “As Carnegie was to steel,” Jenkins and Hines perceptively observe, “Gaston was to dying” (p. 156).

Over time, Gaston branched out into other ventures, including the Booker T. Washington Business College; the Brown Belle Bottling Company (his only significant failure); the Citizens Federal Savings and Loan Association, one of the leading black-owned banks in the United States; and the A. G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham. The motel, which opened in 1954, featured performances by such entertainers as Stevie Wonder and Little Richard, and the guest list included Colin Powell.

Throughout his life, Gaston persistently but quietly and discreetly promoted voting rights and equal treatment for blacks. As early as the 1920s, he was urging his customers not only to save their money, but to register. Many whites did not appreciate this activity. “We were constantly plagued with traffic citations,” Gaston recalled. “We couldn’t park cars or hearses in front of our building. Our employees could not drive to make a bank deposit without getting a ticket on some pretext” (p. 112). Thirty years later, Autherine Lucy rode to campus in Gaston’s car in 1956 when she registered as the first black student at the University of Alabama, and he gave her financial aid. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, such key civil rights leaders as Fred Shuttlesworth, King, and Ralph Abernathy rented the Gaston Motel’s best suite at reduced rates for use as a “war room” (p. 195) to plan civil rights actions. In retaliation, someone planted a bomb that blew off the motel’s facade in 1963.

Gaston’s wealth and cordial ties with the white elite gave him a certain amount of clout that others did not have. His favorite methods were quiet negotiation, deal making, and, if necessary, private threats. He was often effective. For example, the “White’s Only” signs on the drinking fountains of the First National Bank came down after Gaston threatened to pull his account. Many have forgotten the extent to which blacks were exerting economic pressure successfully to bring integration in the decade before the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Like his mentor Washington, however, Gaston always put greater stress on long-term economic improvement than on short-term civil rights struggles. More than once, this approach put him at odds with men such as Fred Shuttlesworth and King, who wanted to push faster and to deemphasize quiet compromise. Events such as the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing and Bull Connor’s decision to sic the dogs on protestors prompted Gaston at times to take action faster than he would have liked. More than a few resented his display of wealth, which included a palatial home. In 1972, Gaston reportedly lamented that the “only thing the black people had against me was I was a success” (p. 252).

During the 1960s, Gaston was a voice in the wilderness as an apostle of the need for blacks to accumulate “Green Power” by going into business. Only in the last few years before his death at age 103 in 1996 was he able to witness the first glimmerings of a reawakened interest in the importance of business enterprise.

Black Titan is a well-written and balanced study of one of the leading black entrepreneurs of the twentieth century. Jenkins and Hines put Gaston into the broader context of black history and give proper due to the influence of Booker T. Washington and the enabling role of mutual-aid networks. Although the authors are Gaston’s relatives, they never lose their scholarly detachment. The book features a nuanced and enlightening discussion of Gaston’s complex relationship with the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. For example, the authors note that although the more radical Shuttlesworth and the more conservative Gaston often tangled, they also knew how to team up through a “good cop—bad cop” (p. 185) approach to achieve common objectives. None other than Ralph Abernathy, the future president of Southern Christian Leadership Conference, later characterized Gaston as “very sympathetic to our cause and very generous with his financial support” (p. 196).

Jenkins and Hines are on shakier ground, however, in some broad generalizations about U.S. economic history. For example, they dismiss as a “trap” (p. 68) the company town of Westfield, Alabama, where Gaston was a miner, because workers there paid excessive prices and rents and were condemned to perpetual debt. But they never give a source to back up this claim. They also do not consider the work of such authors as Price V. Fishback on this subject (Soft Coal, Hard Choices: The Economic Welfare of Bituminous Coal Miners, 1890–930 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992]). Fishback found that overall prices and rents in company towns were not unusually high and that most workers did not carry burdensome long-term debt. If the company town of Westfield was an exception to this picture, the authors should have told us more about how and why.

A few errors and omissions also creep into the analysis of the Great Depression. Jenkins and Hines attribute the crisis to one of two causes: unequal distribution of wealth or uncontrolled speculation. They do not consider the influence of monetary factors or bad policies such as the tariff increases. They favorably quote Howard Zinn’s contention that companies cut wages “again, and again” (p. 103), but they do not mention the evidence showing that real wages were actually higher in 1933 than in 1929 (see Richard K. Vedder and Lowell E. Galloway, Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America [New York: New York University Press, 1993]). Jenkins and Hines also report that the rate of starvation in New York City quadrupled in 1934 over the previous year “despite Hoover’s proclamations to the contrary” (p. 104). A key problem with this claim is that Hoover left office in March 1933.

Jenkins and Hines note that Gaston was a long-time Democrat but do not explain how this affiliation came about. They do not discuss his attitude toward the Republican Party, which as late as 1956 received the votes of Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and other prominent blacks. Given Gaston’s conservative views, the question naturally arises: Why didn’t he support the party of Lincoln?

The authors might have considered more the extent to which the civil rights movement was the by-product of the economic foundation first laid by individuals such as Washington and Gaston. Sometimes the authors needlessly second-guess Gaston’s decisions. Noting that Gaston made a “significant profit” during the depression by purchasing government scrip from teachers for fifty cents on the dollar and later redeeming the scrip at face value when the crisis passed, they add: “If Gaston had reservations about the ethics of the exchange, he never mentioned them” (p. 108). Readers might ask in return: Why should Gaston have had reservations? Wasn’t he performing a service at a considerable long-term personal risk?

These criticisms, most of which relate to background issues, do not undermine the book’s considerable strengths. Jenkins and Hines are at their best when they focus on Arthur G. Gaston as a man, an entrepreneur, and a community leader. Most important, they shed more light on a subject that historians still neglect: the pioneering role that black entrepreneurs played as engineers and drivers of black economic uplift and civil rights.

http://www.npr.org/2010/12/21/132089160/a-g-gaston-from-log-cabin-to-funeral-home-mogul

http://www.independent.org/publications/tir/article.asp?a=579

Add on

By the 1960s, Arthur G. Gaston was probably the richest black man in America. He was the leading employer of blacks in Alabama and directly and indirectly gave substantial aid and comfort to the civil rights movement. In the decade after the Montgomery bus boycott, Martin Luther King Jr. and his allies used the A. G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham, Alabama, as a safe refuge to plan their activities. When Eugene “Bull” Connor, the notorious commissioner of public safety, had King arrested in 1963, Gaston put up the $160,000 bail money from his own pocket.

Despite these contributions, Gaston’s name does not appear in three main survey texts of black history: Darlene Clark Hines’s The African-American Odyssey (Upper Saddle River, N. J.: Prentice Hall, 2005); Joe William Trotter Jr.’s The African-American Experience (New York: Houghton-Mifflin, 2000); and John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994). All three compound their neglect by failing to mention other leading black entrepreneurs, such as the remarkable S. B. Fuller, Gaston’s main business rival during the 1950s and 1960s.

In writing Black Titan, a full-length biography, Carol Jenkins (Gaston’s niece) and Elizabeth Gardner Hines (his grandniece) have taken an important step toward making up for these omissions. Moreover, they show how Gaston was both a product of and a direct participant in a long tradition of black engagement in business, self-help, and mutual aid.

Born in 1893, Gaston grew up in poverty in the small town of Demopolis, Alabama. He was the son of a manual railroad worker and a cook for a prominent white family. When he was a teenager, the entire family moved to the booming industrial city of Birmingham, Alabama. His mother went to work for A. B. Loveman, a wealthy Jewish department store owner.

As is true for most entrepreneurs, Gaston’s rise up the economic ladder can be traced to a combination of luck and pluck. The connection to the Loveman family nurtured a favorable environment for a future business career. Loveman stood out as a model of how to prosper through long hours of hard work and careful attention to investments. The philanthropies of his wife, Minnie Loveman, were instrumental in Gaston’s decision to enroll as a student at the Tuggle Institute.

The institute’s organizational founder and chief sponsor was the Order of Calanthe, the women’s auxiliary of the Colored Knights of Pythias. Among black fraternal societies, the Knights represented a major force for mutual aid and social mobilization in the decades after the Civil War. The Tuggle Institute closely followed Booker T. Washington’s teaching methods of “industrial education” in the skilled trades and business. The Wizard of Tuskegee often visited the campus to deliver speeches of encouragement. From then on, Gaston was an enthusiastic disciple. Washington’s autobiography Up from Slavery was the first book he owned. Gaston’s favorite passage stated that “[e]very persecuted individual and race should get much consolation out of the great human law, which is universal and eternal, that merit, no matter under what skin found, is in the long run recognized and rewarded.... [T]he Negro ... should make himself, through skill, intelligence, and character, of such undeniable value to the community in which he lived that the community could not dispense with his presence” (qtd. on p. 41).

Although A. B. Loveman’s example and the education received at the Tuggle Institute helped to propel Gaston forward, it took many years for him to make significant headway. He fortunately took note of the trials and errors of earlier black businessmen in Birmingham, such as the bankers Charles M. “Boss” Harris and William Pettiford.

After serving in World War I, Gaston drove a delivery truck for a white-owned dry-cleaning company and, at perhaps the lowest point of his life, toiled as a coal miner. He was always alert to any opportunity to better his condition, though, no matter how modest. He tried out an idea to turn a profit by selling boxed lunches prepared by his mother to his fellow miners. It was such a success that he started to sell popcorn and peanuts on the side. Gaston saved an amazing two-thirds of his combined income at this time. Once he had enough money in hand, he took on the informal role of banker, extending loans at 25 percent interest to his coworkers.

Soon Gaston quit mining to set up the Booker T. Washington Burial Society, originally modeled after a fraternal order. It prospered in great part because of his carefully crafted alliance with black ministers who steered business to it from their congregations. He attracted still more customers by sponsoring gospel singers as well as Alabama’s “first regular Negro radio program” (p. 99).

Gaston was a pioneer among black entrepreneurs in the aggressive use of vertical integration. He began with insurance but moved on to control other parts of the process, such as undertaking and casket manufacturing. He also purchased a cemetery. “As Carnegie was to steel,” Jenkins and Hines perceptively observe, “Gaston was to dying” (p. 156).

Over time, Gaston branched out into other ventures, including the Booker T. Washington Business College; the Brown Belle Bottling Company (his only significant failure); the Citizens Federal Savings and Loan Association, one of the leading black-owned banks in the United States; and the A. G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham. The motel, which opened in 1954, featured performances by such entertainers as Stevie Wonder and Little Richard, and the guest list included Colin Powell.

Throughout his life, Gaston persistently but quietly and discreetly promoted voting rights and equal treatment for blacks. As early as the 1920s, he was urging his customers not only to save their money, but to register. Many whites did not appreciate this activity. “We were constantly plagued with traffic citations,” Gaston recalled. “We couldn’t park cars or hearses in front of our building. Our employees could not drive to make a bank deposit without getting a ticket on some pretext” (p. 112). Thirty years later, Autherine Lucy rode to campus in Gaston’s car in 1956 when she registered as the first black student at the University of Alabama, and he gave her financial aid. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, such key civil rights leaders as Fred Shuttlesworth, King, and Ralph Abernathy rented the Gaston Motel’s best suite at reduced rates for use as a “war room” (p. 195) to plan civil rights actions. In retaliation, someone planted a bomb that blew off the motel’s facade in 1963.

Gaston’s wealth and cordial ties with the white elite gave him a certain amount of clout that others did not have. His favorite methods were quiet negotiation, deal making, and, if necessary, private threats. He was often effective. For example, the “White’s Only” signs on the drinking fountains of the First National Bank came down after Gaston threatened to pull his account. Many have forgotten the extent to which blacks were exerting economic pressure successfully to bring integration in the decade before the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Like his mentor Washington, however, Gaston always put greater stress on long-term economic improvement than on short-term civil rights struggles. More than once, this approach put him at odds with men such as Fred Shuttlesworth and King, who wanted to push faster and to deemphasize quiet compromise. Events such as the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing and Bull Connor’s decision to sic the dogs on protestors prompted Gaston at times to take action faster than he would have liked. More than a few resented his display of wealth, which included a palatial home. In 1972, Gaston reportedly lamented that the “only thing the black people had against me was I was a success” (p. 252).

During the 1960s, Gaston was a voice in the wilderness as an apostle of the need for blacks to accumulate “Green Power” by going into business. Only in the last few years before his death at age 103 in 1996 was he able to witness the first glimmerings of a reawakened interest in the importance of business enterprise.

Black Titan is a well-written and balanced study of one of the leading black entrepreneurs of the twentieth century. Jenkins and Hines put Gaston into the broader context of black history and give proper due to the influence of Booker T. Washington and the enabling role of mutual-aid networks. Although the authors are Gaston’s relatives, they never lose their scholarly detachment. The book features a nuanced and enlightening discussion of Gaston’s complex relationship with the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. For example, the authors note that although the more radical Shuttlesworth and the more conservative Gaston often tangled, they also knew how to team up through a “good cop—bad cop” (p. 185) approach to achieve common objectives. None other than Ralph Abernathy, the future president of Southern Christian Leadership Conference, later characterized Gaston as “very sympathetic to our cause and very generous with his financial support” (p. 196).

Jenkins and Hines are on shakier ground, however, in some broad generalizations about U.S. economic history. For example, they dismiss as a “trap” (p. 68) the company town of Westfield, Alabama, where Gaston was a miner, because workers there paid excessive prices and rents and were condemned to perpetual debt. But they never give a source to back up this claim. They also do not consider the work of such authors as Price V. Fishback on this subject (Soft Coal, Hard Choices: The Economic Welfare of Bituminous Coal Miners, 1890–930 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992]). Fishback found that overall prices and rents in company towns were not unusually high and that most workers did not carry burdensome long-term debt. If the company town of Westfield was an exception to this picture, the authors should have told us more about how and why.

A few errors and omissions also creep into the analysis of the Great Depression. Jenkins and Hines attribute the crisis to one of two causes: unequal distribution of wealth or uncontrolled speculation. They do not consider the influence of monetary factors or bad policies such as the tariff increases. They favorably quote Howard Zinn’s contention that companies cut wages “again, and again” (p. 103), but they do not mention the evidence showing that real wages were actually higher in 1933 than in 1929 (see Richard K. Vedder and Lowell E. Galloway, Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America [New York: New York University Press, 1993]). Jenkins and Hines also report that the rate of starvation in New York City quadrupled in 1934 over the previous year “despite Hoover’s proclamations to the contrary” (p. 104). A key problem with this claim is that Hoover left office in March 1933.

Jenkins and Hines note that Gaston was a long-time Democrat but do not explain how this affiliation came about. They do not discuss his attitude toward the Republican Party, which as late as 1956 received the votes of Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and other prominent blacks. Given Gaston’s conservative views, the question naturally arises: Why didn’t he support the party of Lincoln?

The authors might have considered more the extent to which the civil rights movement was the by-product of the economic foundation first laid by individuals such as Washington and Gaston. Sometimes the authors needlessly second-guess Gaston’s decisions. Noting that Gaston made a “significant profit” during the depression by purchasing government scrip from teachers for fifty cents on the dollar and later redeeming the scrip at face value when the crisis passed, they add: “If Gaston had reservations about the ethics of the exchange, he never mentioned them” (p. 108). Readers might ask in return: Why should Gaston have had reservations? Wasn’t he performing a service at a considerable long-term personal risk?

These criticisms, most of which relate to background issues, do not undermine the book’s considerable strengths. Jenkins and Hines are at their best when they focus on Arthur G. Gaston as a man, an entrepreneur, and a community leader. Most important, they shed more light on a subject that historians still neglect: the pioneering role that black entrepreneurs played as engineers and drivers of black economic uplift and civil rights.

http://www.npr.org/2010/12/21/132089160/a-g-gaston-from-log-cabin-to-funeral-home-mogul

http://www.independent.org/publications/tir/article.asp?a=579

Add on