You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Official Syria 🇸🇾 Thread

More options

Who Replied?ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

Syria's only female minister pushes for change: 'I'm not here for window dressing' — BBC News

The BBC's Lyse Doucet follows Hind Kabawat as she confronts the challenges of fragmented, post-Assad Syria.

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

The Fall of the House of Assad

A detached ruler, obsessed with sex and video games, refused every lifeline he was offered.

@bnew

The Fall of the House of Assad

A detached ruler, obsessed with sex and video games, refused every lifeline he was offered.www.theatlantic.com

@bnew

The Fall of the House of Assad

A detached ruler, obsessed with sex and video games, refused every lifeline he was offered.

The Fall of the House of Assad

A detached ruler, obsessed with sex and video games, refused every lifeline he was offered.

By Robert F. Worth

Chris McGrath / Getty

February 6, 2026

Some dictators go down fighting. Some are lynched and strung up for their victims to spit on. Some die in bed.

Bashar al-Assad, who oversaw the torture and murder of hundreds of thousands of his fellow Syrians during a quarter century in power, may have achieved something new in the annals of tyranny. As the rebels closed in on Damascus on December 7, 2024, Assad reassured his aides and subordinates that victory was near, and then fled in the night on a Russian jet, telling almost no one. I remember seeing a statement issued that same evening declaring that Assad was at the palace performing his “constitutional duties.” Some of his closest aides were fooled and had to escape the country however they could as rebel militias lit up the sky with celebratory gunfire.

Assad’s betrayal was so breathtakingly craven that some people had trouble believing it at first. When the facts became impossible to deny, the loyalty of thousands of people curdled almost instantly into fury. Many swore that they had always secretly hated him. There is an expression in Arabic for this kind of revisionist memory: When the cow falls, the butchers multiply.

But the emotion was real for many, as was the belief that Assad was solely responsible for everything that had gone wrong. “You can still find people who believe in Muammar Qaddafi, who believe in Saddam Hussein,” Ibrahim Hamidi, a Syrian journalist and editor, told me. “No one now believes in Bashar al-Assad, not even his brother.”

The sudden collapse of the Assad regime put an end to a cruel police state, but now there is virtually no Syrian state at all outside the capital. The country’s new leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, has done a superb job of charming Donald Trump and other world leaders. He is also an Islamist whose authority is tenuous, and whose country remains so dangerously volatile that it could easily descend into another war.

No one—not the CIA, not the Mossad—appears to have had any idea that Assad would fall so fast. But in the days and weeks afterward, an explanation for his regime’s collapse began to gain currency. Assad’s backers, Russia and Iran, had been drawn into other conflicts, with Ukraine and Israel respectively, and no longer had the ability to protect him. Their sudden withdrawal exposed what had been hidden in plain sight for years: the terrible weakness of an exhausted, corrupt, and underpaid army. A little like the American-backed regime in Afghanistan that fell in 2021, the Assad dynasty was the casualty of broader geopolitical realignments. After the fact, its fall came to seem inevitable.

But over the past year, I have spoken with dozens of the courtiers and officers who inhabited the palace in Damascus, and they tell a different story. Many describe a detached ruler, obsessed with sex and video games, who probably could have saved his regime at any time in the past few years if he hadn’t been so stubborn and vain. In this version, it was not geopolitics that doomed the regime. None of the countries in the region wanted Assad to fall, and several of them offered him lifelines. If he had taken hold of them, he would almost certainly be sitting in the palace now. Even in the final days, foreign ministers were calling, offering deals. He didn’t answer. He appears to have been sulking, angered by the suggestion that he might have to give up the throne.

In the end, Assad’s embittered loyalists may have been right. It was all about Bashar.

Emin Özmen / Magnum Photos

Syrians celebrate the fall of the Assad regime in Damascus in December 2024.

Perhaps all autocrats come to think of themselves as invincible, but Assad had a particular reason for his misplaced confidence: He had already survived one near-death experience.

The Arab Spring uprisings reached Syria in 2011 and blazed up into civil war. A large portion of the country’s people took up arms against its ruler, and scarcely anyone expected Assad to survive. “I have no doubt that the Assad regime will soon discover that the forces of change cannot be reversed,” Barack Obama declared in 2012. Obama was so confident that his State Department helped fund a “Day After Project” to be ready for the new Syria. My editors at The New York Times asked me to write an obituary of the Assad dynasty, and I remember thinking that I should get it done quickly. I still have it in my files.

Read: The dispute behind the violence in Syria

That obituary probably would have been published in 2015 if not for a deus ex machina named Vladimir Putin. A Russian intervention that began in September of that year changed everything for Assad. Waves of deadly air strikes by Russia’s Sukhoi and Tupolev jets, working in concert with Iranian and Shiite militias, shifted the momentum on the battlefield, inflicting fierce blows on the rebel forces. By now, the Syrian opposition, once led by nonviolent protesters, was dominated by Islamists, who were divided and feckless and could be easily lumped together with the telegenic savageries of the Islamic State, known as ISIS.

By late 2017, Assad had more or less won the war. His regime controlled the major cities, and the opposition was confined to the northwestern province of Idlib, where a former al-Qaeda leader named Ahmed al-Sharaa (then known as Abu Muhammad al-Jolani) was emerging as a leading figure.

That deceptive moment of victory, many Syrians have told me, was when everything started to go wrong. Assad didn’t seem to understand that his triumph was a hollow one. Large portions of his country had been reduced to rubble. The economy had shrunk almost to nothing, and sanctions levied by the United States and Europe were weighing it down even further. Syria’s sovereignty had been partly mortgaged to Russia and Iran, which were squeezing Damascus for money to repay their investment in the conflict. Assad’s supporters, having suffered through years of war and struggle, would not remain patient forever. With the fighting over, they began to expect some kind of reprieve.

Assad could have given his people what they wanted. The Gulf Arab states had the money and clout to bring him in from the cold, and in 2017, the United Arab Emirates began reaching out to Damascus. But it had a condition, the same one it had been seeking since before the civil war: Assad had to distance himself from Iran. The Gulf Arabs had long seen the revolutionary theocrats in Tehran as their biggest threat, and Syria’s long-standing alliance with them—forged by Bashar’s father, Hafez al-Assad—was a sore point with all of the other Arab leaders.

For Syria, exchanging Iran’s dubious company for the wealth of the Gulf made a lot of sense. But there was a catch: It wasn’t necessarily the best thing for the Assad family. Unlike the Gulf states and the West, the Iranians had always made clear that they would do anything to keep Assad in power. All he had to do in return was continue to facilitate Tehran’s provision of weapons and money through Syrian territory to Hezbollah, the powerful Lebanese militia that was the star player in Tehran’s “Axis of Resistance.”

Assad did reach a modest rapprochement with the Emiratis, who reopened their embassy in Damascus in 2018. But he refused to cut his ties to Iran. Khaled al-Ahmad, a shrewd political operator in Assad’s inner circle who had negotiated the deal with the Emiratis and had briefly believed that a real political transition was possible, finally concluded that Assad was incapable of changing course. “I decided he was a dead elephant in the room,” he told me of Assad. (Ahmad is now an adviser to the new Syrian government.)

Around this time, a young Israeli national-security official reached the same conclusion and began urging his superiors to organize an internal coup against Assad. The Israelis had long viewed Assad as a manageable enemy—someone who mouthed all of the usual slogans about the Zionist enemy but kept the border between the two countries quiet. But the Israeli official, who is no longer in government service and spoke with me on the condition of anonymity, told me that around 2019, he began to fear that Assad was too feckless to be reliable. “The regime was an empty shell,” he said.

UAE Presidential Court Handout / Andalou / Getty

Assad meets with the president of the United Arab Emirates, Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, in Abu Dhabi on March 19, 2023.

The Israeli command demurred on the coup proposal. The idea had been discussed periodically over the years in Tel Aviv and Washington but had never gotten very far, perhaps because Assad’s father had deliberately created a regime that kept potential rivals in check or under surveillance.

“Everybody in the region was comfortable with him being there,” the former Israeli official said. “Being weak, posing a threat to no one.”

Assad apparently mistook this tacit consensus for power. “Bashar was living in a fictional world,” a former Hezbollah political operative who was often in Syria during those years told me (he asked for anonymity for fear of repercussions): “The Iranians need me. The Russians have no choice. I’m the king.”

Assad’s backers began to grumble, but the Syrian leader wouldn’t listen. In 2019, the former Hezbollah operative said, the Russians and the Iranians began pushing him to make mostly symbolic reforms that would placate Western countries and ease the burden of Syria’s economic isolation. Assad lied and temporized, the official said. Iran’s foreign minister at the time, Mohammad Javad Zarif, said in a recent interview with Al Jazeera that he’d urged Assad to “engage with the opposition” but that the Syrian leader, “drunk with victory,” had stalled.

Read: The honeymoon is ending in Syria

Perhaps the most arresting example of Assad’s obtuseness came during the first Trump administration. In 2020, Washington sent two officials, Roger Carstens and Kash Patel, to Lebanon to locate Austin Tice, an American journalist who had disappeared in Syria in 2012 and was thought to be in the hands of the Assad regime. Abbas Ibrahim, then the head of Lebanon’s General Security branch, brought the two men to Damascus, where they met with one of Assad’s top security officials, a widely feared figure named Ali Mamlouk. The Americans raised the subject of Tice, Carstens told me, and Mamlouk responded that the United States would need to lift sanctions and remove its troops from Syria before any American request could be discussed. Ibrahim, who had taken part in the meeting and recalled some details differently, told me that he had seen Mamlouk’s remark as an opening gambit and had never expected the Americans to make such sweeping concessions.

To the surprise of both Ibrahim and Mamlouk, the U.S. government signaled its agreement to a deal in exchange for proof that Tice was alive. Ibrahim then flew to Washington, where he was told that Trump had confirmed the American position. But Ibrahim was even more amazed when he got the response from Assad: No deal, and no more talks. Ibrahim asked why, and Mamlouk told him that it was “because Trump described Assad as an animal” years earlier.

Ibrahim told his Syrian counterpart that this was madness. Even if Tice was dead, the Americans would hold up their end of the deal as long as they could find out what had happened to him and “close the file.” (There have been conflicting reports about what happened to Tice, including some suggesting, without proof, that an Assad-regime officer may have killed him.) The Americans were eager for anything they could get, Ibrahim recalled to me: “I got a call from Pompeo once; he said, I’m ready to fly by private jet to Syria, ready to shake hands with anyone.” (Pompeo and Patel did not respond to my requests for comment.)

This was a “golden opportunity” for Assad, who presumably could have met with Mike Pompeo, then the U.S. secretary of state, and told him apologetically that the regime did not know what had happened to Tice, Ibrahim said. The meeting alone would have bestowed a new legitimacy on Assad, and made other countries more inclined to reach out to him.

The Biden administration renewed the offer in 2023, sending a high-level delegation to Oman to meet with Syrian officials about Tice. This time, Assad behaved almost insultingly, Ibrahim said, refusing even to send a senior official to meet them. Instead, he sent a former ambassador who was given strict instructions to not so much as speak about Tice.

That Assad, with his hubris and lack of foresight, was soon to fall may be less puzzling, in retrospect, than the fact that he lasted so long. The reason he did goes back to his father, who built a regime so sturdy and ruthless that it survived 25 years of the son’s mismanagement. One lesson to be drawn from Assad’s fall is a very old one: The greatest vulnerability of all political dynasties is the problem of succession.

Hafez al-Assad was a dictator in the classic mold, a shrewd and strong-willed man who rose from rural poverty through the military and seized power in a 1970 coup. He had a genius for undermining and outwitting his rivals, and he made dictatorship seem natural. It was what many Syrians wanted after the chaotic years that followed their country gaining independence from France, in 1946. “For some reason it seems to me that within the Arab circle there is a role wandering aimlessly in search of a hero,” wrote Gamal Abdel Nasser, the lantern-jawed Egyptian leader who embodied that heroic role perfectly in the 1950s and ’60s and helped create the modern idea of what an Arab dictator should be.

Bashar was different. Even first-time visitors to Syria could see that he didn’t look the part: He had a weak chin and panicky eyes, and his head and neck were oddly elongated, as if he’d been squeezed too tight in the birth canal. When you saw his image on one of the ubiquitous billboards around Syria, it was easy to get the feeling that someone had played a practical joke and substituted the head of an anxious schoolboy for that of the leader.

When he started talking, the impression was even worse. His voice was thin and nasal, and he always looked uncomfortable during speeches, as if he was desperate to get it over with. In a culture that puts great value on eloquence and authority, he had none.

Many people who know Bashar told me that his lack of confidence stems from his early years. His older brother, Bassel, bullied his younger siblings so mercilessly that he permanently distorted their personalities, one former palace insider told me. The family dynamics are on display in a famous photograph taken around 1993. Bassel stands at the center of the frame, looking cocky and slightly bored, with his parents seated in front of him and his siblings on either side. Bashar is on the left, his body slightly angled away, his face uneasy. Unlike the others, he seems to be looking beyond the photographer, as if scouting an escape route.

Bashar came to power through an accident. Bassel, a military officer and a show-jumping equestrian who was known as Syria’s “Golden Knight,” was the heir apparent. But he died in a car crash in 1994. Hafez yanked Bashar back from London, where he’d been training to be an ophthalmologist, and began grooming him as the next leader.

Louai Beshara / AFP / Getty

Syrian President Hafez al-Assad and his wife, Anisa, with their children—Maher, Bashar, Bassel, Majd, and Bushra—in a photo thought to have been taken around 1993

Read: Can one man hold Syria together?

Many in Syria’s dissident circles at first found Bashar’s awkwardness and shyness appealing. The fact that he didn’t resemble a dictator kindled their hopes that he would be kinder and more tolerant. For a brief moment, that appeared to be true. During the “Damascus Spring” that followed Bashar’s accession after his father’s death, in 2000, the margin of free speech seemed to widen.

But a crackdown soon followed, and in the following years, Assad’s psychology appeared to be working in the opposite direction. He was so afraid of being perceived as weak, he seemed to believe that he had to prove, again and again, that he could live up to the brutality that was expected of him.

I have spoken with at least a dozen people who knew Assad, and they all commented on his stubbornness. He doesn’t listen to advice, many of them said, and often seems to resent hearing it. Similar things were said about his father, a famously uncompromising negotiator. Both men had to “bargain with and manipulate sinecures of power within this opaque system in order to reach consensus,” David Lesch, a scholar at Trinity University who interviewed Bashar extensively in the 2000s, told me. But Assad lacked his father’s native toughness. According to some who knew and studied him, his rigidity masked a lack of confidence in his own judgment.

That insecurity, some told me, also makes him impressionable. He was particularly taken with Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, an immensely popular and charismatic figure. Assad seems to have believed the propaganda Nasrallah fed him, perhaps because it was what he wanted to hear: that the Axis of Resistance would strike a fierce blow against Israel and that, afterward, Assad would be able to set any conditions he liked for peace. In other words, Assad would not have to make any difficult choices or sacrifices. Everything would be handed to him on a platter.

On October 7, 2023, Assad must have imagined for a few hours that Nasrallah’s prophecies had come true. Hamas fighters swept across the border fence from Gaza and massacred more than 1,000 people. Israel—the Samson of the region—looked weak and unprepared.

But before long, Israel was launching thousands of air strikes not just into Gaza but also into Lebanon and Syria. Assad said nothing about this campaign against his allies, which eventually killed Nasrallah himself. Perhaps he hoped to keep his name off Israel’s target list. But according to Wiam Wahhab, a Lebanese political figure who was close to the Syrian regime, Assad’s silence fueled Iranian suspicions that he was feeding information to the Israelis. The Axis of Resistance was falling apart.

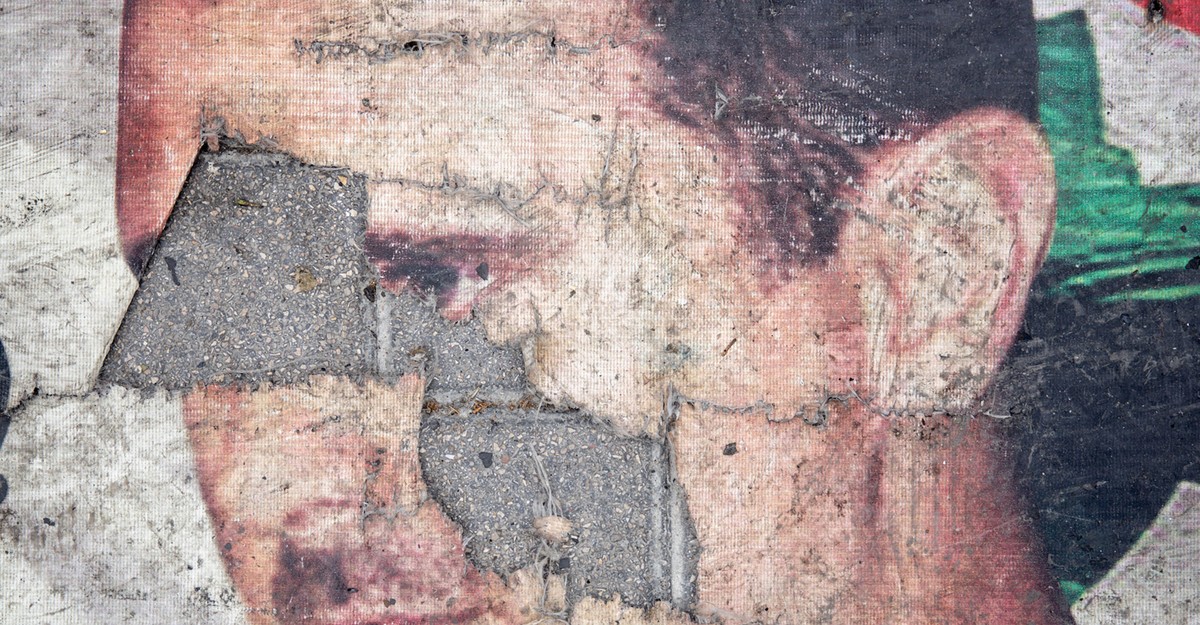

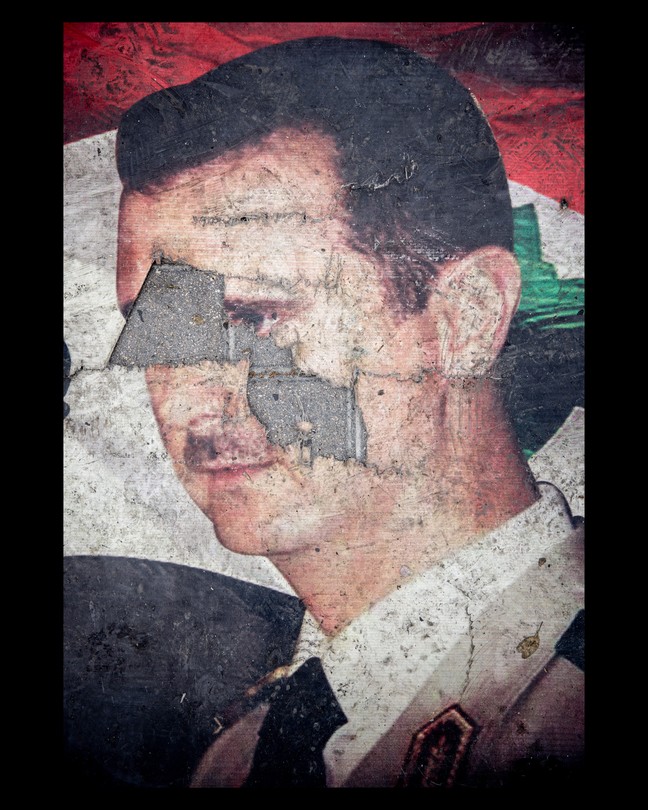

Bakr Alkasem / AFP / Getty

A rebel fighter shoots at a banner displaying Assad’s photo outside a municipal building in Hama just after the regime fell.

That should have worried Assad, especially in light of the fact that Russia, his other protector, was bogged down in Ukraine. But the atmosphere at the palace was not conducive to clear thinking. Assad was spending much of his time playing Candy Crush and other video games on his phone, according to the former Hezbollah operative I spoke with. He had sidelined the éminences grises of his father’s day and relied instead on a small circle of younger figures with dubious credentials. One of them, a former Al Jazeera journalist named Luna al-Shibl, doubled as Assad’s lover and also procured other women for him to have sex with, including the wives of high-ranking Syrian officers, according to former palace insiders and the former Israeli official.

Read: The honeymoon is ending in Syria

Perhaps the most arresting example of Assad’s obtuseness came during the first Trump administration. In 2020, Washington sent two officials, Roger Carstens and Kash Patel, to Lebanon to locate Austin Tice, an American journalist who had disappeared in Syria in 2012 and was thought to be in the hands of the Assad regime. Abbas Ibrahim, then the head of Lebanon’s General Security branch, brought the two men to Damascus, where they met with one of Assad’s top security officials, a widely feared figure named Ali Mamlouk. The Americans raised the subject of Tice, Carstens told me, and Mamlouk responded that the United States would need to lift sanctions and remove its troops from Syria before any American request could be discussed. Ibrahim, who had taken part in the meeting and recalled some details differently, told me that he had seen Mamlouk’s remark as an opening gambit and had never expected the Americans to make such sweeping concessions.

To the surprise of both Ibrahim and Mamlouk, the U.S. government signaled its agreement to a deal in exchange for proof that Tice was alive. Ibrahim then flew to Washington, where he was told that Trump had confirmed the American position. But Ibrahim was even more amazed when he got the response from Assad: No deal, and no more talks. Ibrahim asked why, and Mamlouk told him that it was “because Trump described Assad as an animal” years earlier.

Ibrahim told his Syrian counterpart that this was madness. Even if Tice was dead, the Americans would hold up their end of the deal as long as they could find out what had happened to him and “close the file.” (There have been conflicting reports about what happened to Tice, including some suggesting, without proof, that an Assad-regime officer may have killed him.) The Americans were eager for anything they could get, Ibrahim recalled to me: “I got a call from Pompeo once; he said, I’m ready to fly by private jet to Syria, ready to shake hands with anyone.” (Pompeo and Patel did not respond to my requests for comment.)

This was a “golden opportunity” for Assad, who presumably could have met with Mike Pompeo, then the U.S. secretary of state, and told him apologetically that the regime did not know what had happened to Tice, Ibrahim said. The meeting alone would have bestowed a new legitimacy on Assad, and made other countries more inclined to reach out to him.

The Biden administration renewed the offer in 2023, sending a high-level delegation to Oman to meet with Syrian officials about Tice. This time, Assad behaved almost insultingly, Ibrahim said, refusing even to send a senior official to meet them. Instead, he sent a former ambassador who was given strict instructions to not so much as speak about Tice.

That Assad, with his hubris and lack of foresight, was soon to fall may be less puzzling, in retrospect, than the fact that he lasted so long. The reason he did goes back to his father, who built a regime so sturdy and ruthless that it survived 25 years of the son’s mismanagement. One lesson to be drawn from Assad’s fall is a very old one: The greatest vulnerability of all political dynasties is the problem of succession.

Hafez al-Assad was a dictator in the classic mold, a shrewd and strong-willed man who rose from rural poverty through the military and seized power in a 1970 coup. He had a genius for undermining and outwitting his rivals, and he made dictatorship seem natural. It was what many Syrians wanted after the chaotic years that followed their country gaining independence from France, in 1946. “For some reason it seems to me that within the Arab circle there is a role wandering aimlessly in search of a hero,” wrote Gamal Abdel Nasser, the lantern-jawed Egyptian leader who embodied that heroic role perfectly in the 1950s and ’60s and helped create the modern idea of what an Arab dictator should be.

Bashar was different. Even first-time visitors to Syria could see that he didn’t look the part: He had a weak chin and panicky eyes, and his head and neck were oddly elongated, as if he’d been squeezed too tight in the birth canal. When you saw his image on one of the ubiquitous billboards around Syria, it was easy to get the feeling that someone had played a practical joke and substituted the head of an anxious schoolboy for that of the leader.

When he started talking, the impression was even worse. His voice was thin and nasal, and he always looked uncomfortable during speeches, as if he was desperate to get it over with. In a culture that puts great value on eloquence and authority, he had none.

Many people who know Bashar told me that his lack of confidence stems from his early years. His older brother, Bassel, bullied his younger siblings so mercilessly that he permanently distorted their personalities, one former palace insider told me. The family dynamics are on display in a famous photograph taken around 1993. Bassel stands at the center of the frame, looking cocky and slightly bored, with his parents seated in front of him and his siblings on either side. Bashar is on the left, his body slightly angled away, his face uneasy. Unlike the others, he seems to be looking beyond the photographer, as if scouting an escape route.

Bashar came to power through an accident. Bassel, a military officer and a show-jumping equestrian who was known as Syria’s “Golden Knight,” was the heir apparent. But he died in a car crash in 1994. Hafez yanked Bashar back from London, where he’d been training to be an ophthalmologist, and began grooming him as the next leader.

Louai Beshara / AFP / Getty

Syrian President Hafez al-Assad and his wife, Anisa, with their children—Maher, Bashar, Bassel, Majd, and Bushra—in a photo thought to have been taken around 1993

Read: Can one man hold Syria together?

Many in Syria’s dissident circles at first found Bashar’s awkwardness and shyness appealing. The fact that he didn’t resemble a dictator kindled their hopes that he would be kinder and more tolerant. For a brief moment, that appeared to be true. During the “Damascus Spring” that followed Bashar’s accession after his father’s death, in 2000, the margin of free speech seemed to widen.

But a crackdown soon followed, and in the following years, Assad’s psychology appeared to be working in the opposite direction. He was so afraid of being perceived as weak, he seemed to believe that he had to prove, again and again, that he could live up to the brutality that was expected of him.

I have spoken with at least a dozen people who knew Assad, and they all commented on his stubbornness. He doesn’t listen to advice, many of them said, and often seems to resent hearing it. Similar things were said about his father, a famously uncompromising negotiator. Both men had to “bargain with and manipulate sinecures of power within this opaque system in order to reach consensus,” David Lesch, a scholar at Trinity University who interviewed Bashar extensively in the 2000s, told me. But Assad lacked his father’s native toughness. According to some who knew and studied him, his rigidity masked a lack of confidence in his own judgment.

That insecurity, some told me, also makes him impressionable. He was particularly taken with Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, an immensely popular and charismatic figure. Assad seems to have believed the propaganda Nasrallah fed him, perhaps because it was what he wanted to hear: that the Axis of Resistance would strike a fierce blow against Israel and that, afterward, Assad would be able to set any conditions he liked for peace. In other words, Assad would not have to make any difficult choices or sacrifices. Everything would be handed to him on a platter.

On October 7, 2023, Assad must have imagined for a few hours that Nasrallah’s prophecies had come true. Hamas fighters swept across the border fence from Gaza and massacred more than 1,000 people. Israel—the Samson of the region—looked weak and unprepared.

But before long, Israel was launching thousands of air strikes not just into Gaza but also into Lebanon and Syria. Assad said nothing about this campaign against his allies, which eventually killed Nasrallah himself. Perhaps he hoped to keep his name off Israel’s target list. But according to Wiam Wahhab, a Lebanese political figure who was close to the Syrian regime, Assad’s silence fueled Iranian suspicions that he was feeding information to the Israelis. The Axis of Resistance was falling apart.

Bakr Alkasem / AFP / Getty

A rebel fighter shoots at a banner displaying Assad’s photo outside a municipal building in Hama just after the regime fell.

That should have worried Assad, especially in light of the fact that Russia, his other protector, was bogged down in Ukraine. But the atmosphere at the palace was not conducive to clear thinking. Assad was spending much of his time playing Candy Crush and other video games on his phone, according to the former Hezbollah operative I spoke with. He had sidelined the éminences grises of his father’s day and relied instead on a small circle of younger figures with dubious credentials. One of them, a former Al Jazeera journalist named Luna al-Shibl, doubled as Assad’s lover and also procured other women for him to have sex with, including the wives of high-ranking Syrian officers, according to former palace insiders and the former Israeli official.

Shibl, who was married to a regime insider, seems to have encouraged Assad’s palace-born habit of looking down on ordinary citizens. In a recording that surfaced this past December, Assad and Shibl can be heard laughing dismissively about the pretensions of Hezbollah and mocking the soldiers who salute them as they drive through a Damascus suburb. Assad, who is at the wheel, says at one point of the Syrians they pass in the street: “They spend money on mosques, but they don’t have enough to eat.”

To understand the obscenity of Assad’s comment, you need to know that he was amassing an enormous personal fortune, mostly from drug smuggling, even as many Syrians were at the point of starvation. Ordinary soldiers were paid as little as $10 a month, far less than they needed to survive. The Syrian pound, which had once traded at 47 to the dollar, had reached a rate of 15,000 a dollar by 2023. The poverty deepened after 2020, when the U.S. Congress imposed another steep round of sanctions under the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act.

Read: The end of a 13-year nightmare

Even longtime supporters from the Alawite religious minority—the sect to which the Assads belong—began to complain about their destitution. One member of the Assad clan who lives in Europe told me that he’d visited Syria in 2021 and been amazed to discover that the officers—from the elite Republican Guard unit—charged with protecting his immediate family were so poor that they spent their off-duty hours hawking fruit and cigarettes in the street.

Assad and his family maintained their own living standards by turning Syria into a narco-state, with Bashar’s brother Maher overseeing the manufacture and smuggling of immense quantities of Captagon, an illegal amphetamine. The drug trade earned Assad billions of dollars, but it also fueled an addiction crisis in the Gulf states and Jordan, angering their leaders.

Assad’s megalomania seems to have taken a strange new turn in these past few years. According to Ahmad, Assad had concluded that he needed “monarchy tools” like those of Putin and the Gulf rulers, including cash reserves large enough to subsidize militias and reorient the economy. Assad’s comments to a Russian interviewer during his final months in power betray a hint of this idea of royal powers. Asked about the downsides of democracy, Assad said, with a contemptuous grin: “In the West, the presidents, especially in the United States, are the executive directors, but they’re not the owners.”

In July 2024, with the war in Gaza dominating the headlines, Luna al-Shibl was found dead in her BMW on a highway outside Damascus. The regime media called it a road accident, but the circumstances were odd: According to some reports, the car was only lightly damaged, yet her skull had been bashed in. Rumors spread quickly that she had been killed on the orders of Tehran for providing targeting information to the Israelis.

Raghed Waked / Middle East Images / AFP / Getty

A fighter displays Captagon pills found hidden inside an electric transformer in Douma in December 2024.

But Assad was the one who’d ordered the murder of his former lover, the former Israeli official and two people with ties to the regime told me. Shibl had become a de facto Russian agent, providing Moscow with information about Iran’s activities in Syria, the former Israeli official said. Perhaps she’d sensed that the end was coming for Assad and that she needed another protector. This account was impossible to confirm; Russian officials do not comment on intelligence matters.

When a tyrant falls, we may be tempted to imagine a final moment of tragic self-awareness—a personal reckoning, like Oedipus blinding himself, or Macbeth raging on the heath. But I don’t think real dictators go down like that. They are too good at lying to themselves.

For Assad, the final chapter began in November 2024. The rebel militias under Ahmed al-Sharaa’s command had been lobbying for Turkey’s permission to launch a military operation, and finally, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gave it to them. (Turkey denied official involvement in the operation.)

Erdoğan did so reluctantly. All year, he had been asking Assad to meet with him. His demands were pretty modest: a political reconciliation and a deal to allow the millions of Syrian refugees in Turkey to return home. But Assad acted as if he held all the cards, refusing to meet unless Erdoğan agreed in advance to withdraw all Turkish forces from Syria. The rebel operation that Erdoğan approved seems to have been intended as a way to prod Assad to negotiate; it was framed not as an invasion but as a defensive move.

When the rebels marched northeast toward the city of Aleppo on November 27, 2024, Assad was in Russia, where his son would be defending his Ph.D. dissertation on number theory and polynomial representations at Moscow State University. As Aleppo’s defenses crumbled, Assad remained in Moscow, to the shock and dismay of his commanders back home. He seems to have been hoping to persuade Putin to rescue him.

But the Russian president kept him waiting for days, and when they finally met, it was very brief. According to the former Israeli official I spoke with, Putin told Assad that he could not fight his war for him, and that the Syrian leader’s only hope was to go to Erdoğan and cut a deal. The Russians had always valued their strategic relationship with Turkey far more than their relationship with Syria. Whether Assad grasped this is impossible to know. But Putin was not going to launch a new war against Turkey’s rebel allies just to save a petty dictator whose own soldiers were deserting.

Aleppo had fallen to the rebels by the time Assad landed back in Damascus. After only a few hours, he flew to Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates, Ahmad told me. It is not clear whom he met with or what was said. The Emiratis feared Sharaa’s Islamist militias as much as they feared Tehran. But they had no boots on the ground.

Back in Damascus, Assad tried a last gambit, calling on the “monarchy tools” he had been assembling for years. He put out word that he would pay exorbitant salaries to volunteers who could quickly reassemble the militias that had helped win the civil war years earlier, Ahmad told me. But when the ordinary soldiers who’d spent years on starvation wages heard of these offers, many were so furious that they abandoned their post.

The rebels had now captured the city of Hama and were on their way to Homs, 100 miles north of the capital. At the same time, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard commanders who had helped prop up the regime began to pack up and leave. Syrian soldiers got wind of their allies’ retreat, and panic spread among the ranks. The rebels rode southward almost unopposed.

Read: The Axis of Resistance keeps getting smaller

On December 7, 2024, the foreign ministers of Russia and seven Middle Eastern countries held an emergency meeting on the sidelines of an annual security conference in Doha, the Qatari capital. None of them wanted the Assad regime to collapse. They issued a statement calling for an end to military operations and for a phased political transition, based on a United Nations Security Council resolution that had been issued a decade earlier. They would need Assad to agree to this and facilitate it, but there was a problem: No one could reach him. He appeared to have turned off his phone.

A member of Assad’s entourage who was with him in the final hours gave me the following account, asking not to be named because he is still living in the region.

Assad returned from the palace to his private residence in the capital’s al-Malki neighborhood at roughly 6 p.m. He seemed calm, and mentioned that he had just reassured his cousin Ihab Makhlouf that there was nothing to worry about; the Emiratis and Saudis would find a way to stop the rebel advance. Makhlouf was shot to death later that night while fleeing by car to Lebanon.

At 8 p.m., word came that Homs had fallen to the rebels. That struck fear in the entourage. But Assad assured his aides that regime forces were coming from the south to encircle and defend the capital. This was not true, and my sources could not say whether Assad believed it. In the hours that followed, he seemed to have oscillated between despair and deluded assurances that victory was at hand—a state of mind that will be familiar to anyone who has watched the movie Downfall, about Hitler’s final days in the Führerbunker in Berlin.

Omar Haj Kadour / AFP / Getty

Parts of the former presidential palace in Damascus were looted and burned after Assad fled.

Just after 11 p.m., Mansour Azzam, one of Assad’s top aides, arrived at the house with a small group of Russian officials. They went off to a room together with Assad to talk. My source told me he believes that the Russians were showing Assad videos proving that the regime forces were no longer fighting.

By 1 a.m., word had reached the entourage that many regime supporters had given up the fight and were fleeing the capital for the Syrian coast, the Alawite heartland.

At 2 a.m., Assad emerged from his private quarters and told his longtime driver that he would need vans. He gave orders for the staff to start packing his belongings as quickly as possible. A group of Russians was outside the house.

Until that moment, many in the entourage had believed that Assad would go to the presidential palace to deliver a speech of resistance to his followers. Now they finally understood that the battle was over. He was abandoning them for good. Assad moved toward the front door, this time with two of his aides and his son Hafez. The others were told that there was no room for them.

Assad’s middle-aged driver stood by the door, looking at the president with an unmistakable expression of disappointment on his face.

“You’re really leaving us?” he said.

Assad looked back at him. Even in this last moment, he wouldn’t take responsibility for what had happened to his country. He wasn’t betraying his followers—it was they who were betraying him, by refusing to lay down their lives to extend his rule.

“What about you people?” Assad asked the driver. “Aren’t you going to fight?”

He turned and went out into the night. The Russians were waiting.

To understand the obscenity of Assad’s comment, you need to know that he was amassing an enormous personal fortune, mostly from drug smuggling, even as many Syrians were at the point of starvation. Ordinary soldiers were paid as little as $10 a month, far less than they needed to survive. The Syrian pound, which had once traded at 47 to the dollar, had reached a rate of 15,000 a dollar by 2023. The poverty deepened after 2020, when the U.S. Congress imposed another steep round of sanctions under the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act.

Read: The end of a 13-year nightmare

Even longtime supporters from the Alawite religious minority—the sect to which the Assads belong—began to complain about their destitution. One member of the Assad clan who lives in Europe told me that he’d visited Syria in 2021 and been amazed to discover that the officers—from the elite Republican Guard unit—charged with protecting his immediate family were so poor that they spent their off-duty hours hawking fruit and cigarettes in the street.

Assad and his family maintained their own living standards by turning Syria into a narco-state, with Bashar’s brother Maher overseeing the manufacture and smuggling of immense quantities of Captagon, an illegal amphetamine. The drug trade earned Assad billions of dollars, but it also fueled an addiction crisis in the Gulf states and Jordan, angering their leaders.

Assad’s megalomania seems to have taken a strange new turn in these past few years. According to Ahmad, Assad had concluded that he needed “monarchy tools” like those of Putin and the Gulf rulers, including cash reserves large enough to subsidize militias and reorient the economy. Assad’s comments to a Russian interviewer during his final months in power betray a hint of this idea of royal powers. Asked about the downsides of democracy, Assad said, with a contemptuous grin: “In the West, the presidents, especially in the United States, are the executive directors, but they’re not the owners.”

In July 2024, with the war in Gaza dominating the headlines, Luna al-Shibl was found dead in her BMW on a highway outside Damascus. The regime media called it a road accident, but the circumstances were odd: According to some reports, the car was only lightly damaged, yet her skull had been bashed in. Rumors spread quickly that she had been killed on the orders of Tehran for providing targeting information to the Israelis.

Raghed Waked / Middle East Images / AFP / Getty

A fighter displays Captagon pills found hidden inside an electric transformer in Douma in December 2024.

But Assad was the one who’d ordered the murder of his former lover, the former Israeli official and two people with ties to the regime told me. Shibl had become a de facto Russian agent, providing Moscow with information about Iran’s activities in Syria, the former Israeli official said. Perhaps she’d sensed that the end was coming for Assad and that she needed another protector. This account was impossible to confirm; Russian officials do not comment on intelligence matters.

When a tyrant falls, we may be tempted to imagine a final moment of tragic self-awareness—a personal reckoning, like Oedipus blinding himself, or Macbeth raging on the heath. But I don’t think real dictators go down like that. They are too good at lying to themselves.

For Assad, the final chapter began in November 2024. The rebel militias under Ahmed al-Sharaa’s command had been lobbying for Turkey’s permission to launch a military operation, and finally, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gave it to them. (Turkey denied official involvement in the operation.)

Erdoğan did so reluctantly. All year, he had been asking Assad to meet with him. His demands were pretty modest: a political reconciliation and a deal to allow the millions of Syrian refugees in Turkey to return home. But Assad acted as if he held all the cards, refusing to meet unless Erdoğan agreed in advance to withdraw all Turkish forces from Syria. The rebel operation that Erdoğan approved seems to have been intended as a way to prod Assad to negotiate; it was framed not as an invasion but as a defensive move.

When the rebels marched northeast toward the city of Aleppo on November 27, 2024, Assad was in Russia, where his son would be defending his Ph.D. dissertation on number theory and polynomial representations at Moscow State University. As Aleppo’s defenses crumbled, Assad remained in Moscow, to the shock and dismay of his commanders back home. He seems to have been hoping to persuade Putin to rescue him.

But the Russian president kept him waiting for days, and when they finally met, it was very brief. According to the former Israeli official I spoke with, Putin told Assad that he could not fight his war for him, and that the Syrian leader’s only hope was to go to Erdoğan and cut a deal. The Russians had always valued their strategic relationship with Turkey far more than their relationship with Syria. Whether Assad grasped this is impossible to know. But Putin was not going to launch a new war against Turkey’s rebel allies just to save a petty dictator whose own soldiers were deserting.

Aleppo had fallen to the rebels by the time Assad landed back in Damascus. After only a few hours, he flew to Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates, Ahmad told me. It is not clear whom he met with or what was said. The Emiratis feared Sharaa’s Islamist militias as much as they feared Tehran. But they had no boots on the ground.

Back in Damascus, Assad tried a last gambit, calling on the “monarchy tools” he had been assembling for years. He put out word that he would pay exorbitant salaries to volunteers who could quickly reassemble the militias that had helped win the civil war years earlier, Ahmad told me. But when the ordinary soldiers who’d spent years on starvation wages heard of these offers, many were so furious that they abandoned their post.

The rebels had now captured the city of Hama and were on their way to Homs, 100 miles north of the capital. At the same time, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard commanders who had helped prop up the regime began to pack up and leave. Syrian soldiers got wind of their allies’ retreat, and panic spread among the ranks. The rebels rode southward almost unopposed.

Read: The Axis of Resistance keeps getting smaller

On December 7, 2024, the foreign ministers of Russia and seven Middle Eastern countries held an emergency meeting on the sidelines of an annual security conference in Doha, the Qatari capital. None of them wanted the Assad regime to collapse. They issued a statement calling for an end to military operations and for a phased political transition, based on a United Nations Security Council resolution that had been issued a decade earlier. They would need Assad to agree to this and facilitate it, but there was a problem: No one could reach him. He appeared to have turned off his phone.

A member of Assad’s entourage who was with him in the final hours gave me the following account, asking not to be named because he is still living in the region.

Assad returned from the palace to his private residence in the capital’s al-Malki neighborhood at roughly 6 p.m. He seemed calm, and mentioned that he had just reassured his cousin Ihab Makhlouf that there was nothing to worry about; the Emiratis and Saudis would find a way to stop the rebel advance. Makhlouf was shot to death later that night while fleeing by car to Lebanon.

At 8 p.m., word came that Homs had fallen to the rebels. That struck fear in the entourage. But Assad assured his aides that regime forces were coming from the south to encircle and defend the capital. This was not true, and my sources could not say whether Assad believed it. In the hours that followed, he seemed to have oscillated between despair and deluded assurances that victory was at hand—a state of mind that will be familiar to anyone who has watched the movie Downfall, about Hitler’s final days in the Führerbunker in Berlin.

Omar Haj Kadour / AFP / Getty

Parts of the former presidential palace in Damascus were looted and burned after Assad fled.

Just after 11 p.m., Mansour Azzam, one of Assad’s top aides, arrived at the house with a small group of Russian officials. They went off to a room together with Assad to talk. My source told me he believes that the Russians were showing Assad videos proving that the regime forces were no longer fighting.

By 1 a.m., word had reached the entourage that many regime supporters had given up the fight and were fleeing the capital for the Syrian coast, the Alawite heartland.

At 2 a.m., Assad emerged from his private quarters and told his longtime driver that he would need vans. He gave orders for the staff to start packing his belongings as quickly as possible. A group of Russians was outside the house.

Until that moment, many in the entourage had believed that Assad would go to the presidential palace to deliver a speech of resistance to his followers. Now they finally understood that the battle was over. He was abandoning them for good. Assad moved toward the front door, this time with two of his aides and his son Hafez. The others were told that there was no room for them.

Assad’s middle-aged driver stood by the door, looking at the president with an unmistakable expression of disappointment on his face.

“You’re really leaving us?” he said.

Assad looked back at him. Even in this last moment, he wouldn’t take responsibility for what had happened to his country. He wasn’t betraying his followers—it was they who were betraying him, by refusing to lay down their lives to extend his rule.

“What about you people?” Assad asked the driver. “Aren’t you going to fight?”

He turned and went out into the night. The Russians were waiting.