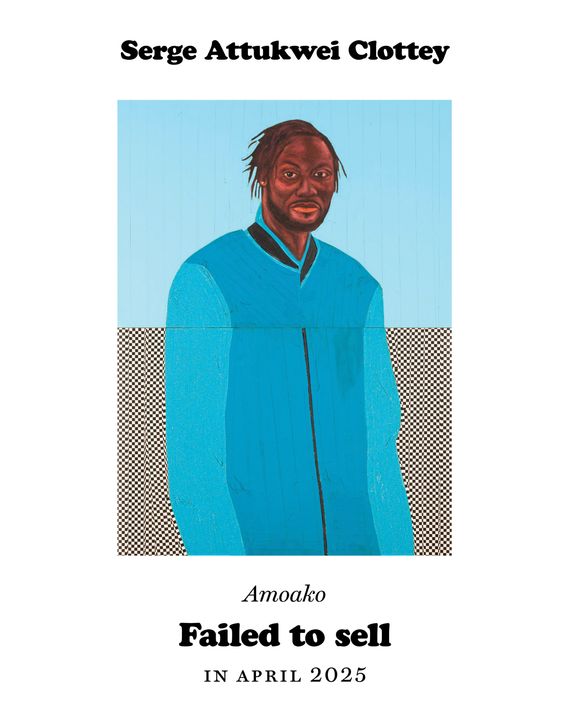

In October 2021, the artist Serge Attukwei Clottey watched anxiously as a painting he had made just a few months earlier went up for sale at the Phillips auction house in London. The portrait — of a stylish Black couple whose clothes were rendered in colorful strips of duct tape — was his first ever to go to auction.

It was “really, really scary,” Clottey, now 39, tells me. He wouldn’t profit directly from the sale — he had already sold the piece to a collector, who had brought it to Phillips — but a low auction price could devalue all his other work. A high price could set off a speculative furor. For years, Clottey had been known mostly for his tapestries, made from tilelike pieces of discarded plastic bottles. One had sold for $6,875 in 2019. But portraiture was a fresh experiment.

The auction house had estimated the value of the painting, titled Fashion Icons, to be between £30,000 and £40,000 — on par with Clottey’s other prices at the time. But in the end it went for ten times that range: £340,000. Over the next few months, Clottey’s paintings were quickly brought to auction, where many sold for six figures.

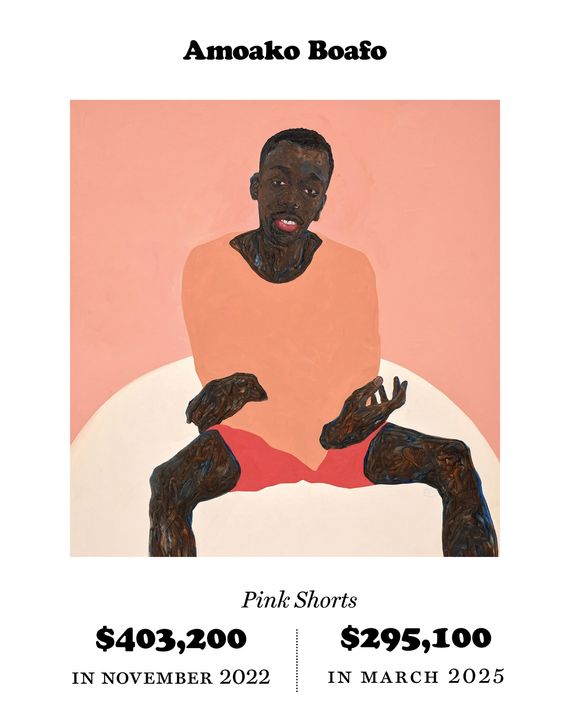

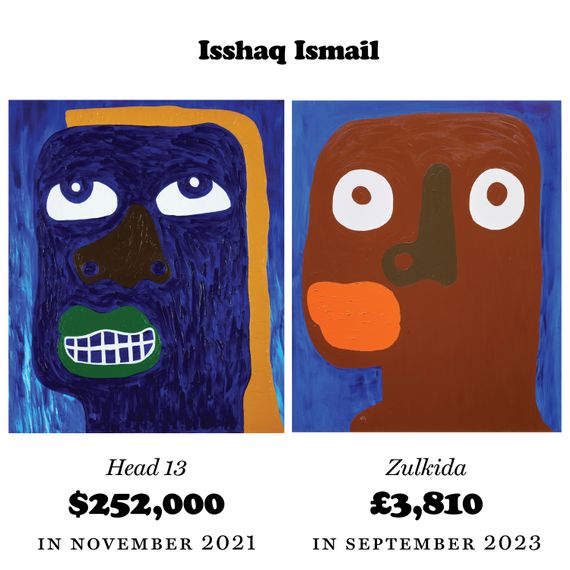

That’s when the “craze” began, Clottey tells me. In late 2021, strangers from around the world started flooding his Instagram, his galleries, and his studio with requests to buy his art. Some showed up in Accra in person. And he wasn’t alone in this surreal experience: The same thing was happening to dozens of other young Black artists, especially those from Africa and those who painted portraits of Black people. A month after the sale of Fashion Icons, Kwesi Botchway, a friend of Clottey’s in Ghana, saw one of his own paintings, a portrait of a red-eyed, indigo-skinned woman, go to auction with an estimated price range of $30,000 to $50,000 and then sell for $214,200. A month after that, another friend in the Accra scene, Isshaq Ismail, watched one of his acrylic-and-collage paintings — part of a series of faces resembling African masks — go up for an estimated $15,000 to $20,000. It sold for $275,000.

Two forces had come together to create a perfect speculative storm. The Black Lives Matter movement had provoked museums to fill racial gaps in their collections and canons; gallerists who realized they didn’t represent a single Black artist suddenly went to recruit them. And collectors — including many Black newcomers to the market — wanted in on the action. At the same time, thanks to falling interest rates, the greater art market was flooded with cash. The economist Clare McAndrew has found that the global art market grew $3.7 billion between 2019 and 2022, ultimately reaching a high of $67.8 billion.

Some saw the fresh enthusiasm for Black artists as a sign of meaningful change. It filled the air with “this optimism, this hope,” says Destinee Ross-Sutton, the New York–and–Stockholm–based adviser and dealer: “Maybe things are finally different. Maybe things are gonna get better. Maybe people are ready to listen and to take us seriously.” But portraiture also offered a shortcut to signaling virtue. There was a direct correlation between the visible content of a painting and the identity of its creator. “Black guy on the wall: Boom. ‘I’m not a racist,’” says the dealer Stefan Simchowitz. Simchowitz was the seller of Clottey’s painting at Phillips but does not consider himself a part of the group in question. “‘I don’t have a Black friend,’” he goes on, impersonating the buyers, “‘but a Kwesi Botchway is in my living room.’”

Seasoned operators saw the opportunity for a quick return and bought in, inflating the bubble. African artists, such as the Ghanaians, were especially vulnerable to speculation: Without being signed to international galleries, which could screen far-flung buyers and sort the true collectors from the flippers, they were at a loss. As Clottey puts it, “Most of us, we didn’t even know who we sold to. You had people just flying down to any African country and finding artists.”

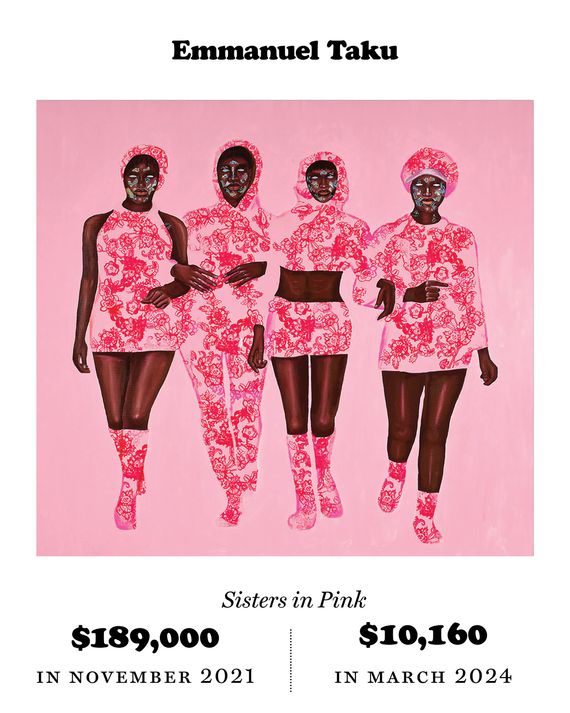

Then, in 2024, the wider art market cooled — notching about $10 billion less in sales than its pandemic high — and younger artists were hit particularly hard. In the first half of the year, sales of work by artists under 40 fell by 39 percent from 2023. By this time, anti-woke sentiment had infected the mainstream and interest in showy egalitarianism and visible diversity was noticeably lower. The fervor for Black portraiture peaked and plummeted in just four years.

Latecoming collectors are now stuck holding pricey paintings they can sell only at a loss. Many artists are left with bodies of work they’ll be lucky to sell at all.

“A lot of people exploited us,” says Botchway, whose paintings were subject to a buying spree until late 2023, after which several publicly flopped: One sold for roughly a third of its presale estimate and one failed to sell at all. Botchway grew up in an Accra slum, where he used to know people who bleached their skin. As a painter, he wanted to show the beauty of Blackness, so he began infusing skin tones with purple, a color signifying royalty and, he says, strength. “There were collectors who didn’t want to even understand what the artist was talking about,” he says.

Like Botchway’s work, Clottey’s paintings were about more than what was apparent at first glance. The duct tape used in Fashion Icons was a reference to Marcus Omofuma, a 25-year-old Nigerian man who died on a 1999 deportation flight after Austrian police gagged and bound him with tape. Simchowitz declined to say how much he had paid Clottey for the painting, but by the artist’s recollection of the price, the dealer would have made about six times what he paid for it at auction. “Serge is a great artist,” Simchowitz says. “I miss the work.” But that’s business, he says: “I realized the market was strong.” He knew it would do very well at Phillips.

Last edited: