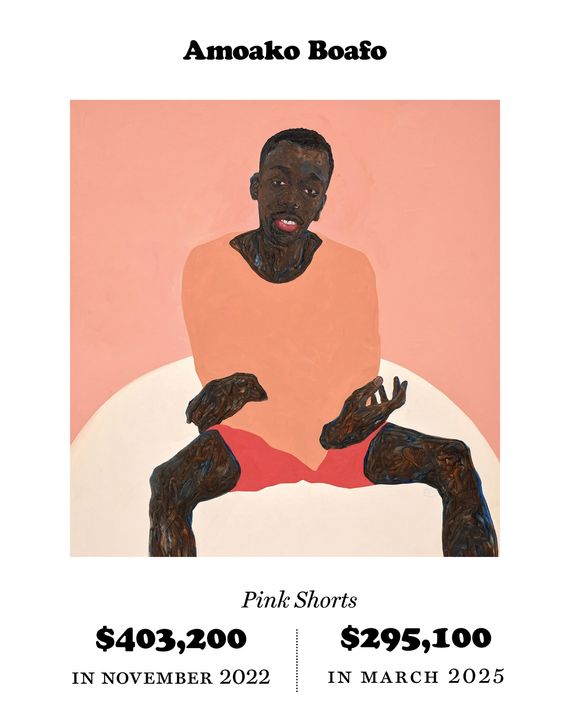

Simchowitz had actually kicked off the craze the year before. In 2019, he’d bought a painting of a Black woman in a lemon-printed bathing suit, by the Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo, for $22,500. In 2020, he auctioned it off for £675,000, an incredible price — unheard of for an artist’s auction debut — setting off a battle for Boafo’s inventory. Before the year was out, dozens of the artist’s paintings — of Black figures in wavering, Egon Schiele–inspired lines — passed through the auction houses and in most cases garnered six figures.

Ross-Sutton knew a crash had to be coming. In 2020, when she organized an online sale for Christie’s of work by artists from Africa and the diaspora, called “Say It Loud,” she decided to build in safeguards: The artists would receive the majority of the proceeds, and buyers signed contracts agreeing not to resell the work for at least five years. If they sold after that period, they would need to first offer to sell the work back to the artist. If the piece was sold to another party, the artist would get 15 percent of the profit.

“Say It Loud” was a runaway success — as was its second iteration in 2021 — and the profile of Black portraiture was raised even higher. People started streaming into Ross-Sutton’s gallery in New York “like it was a car dealership,” she says. “They walked in like, ‘Oh, if I give cash, can I get a deal?’” She tried to separate collectors who genuinely appreciated the art from opportunists, telling them, “I want to know why you decided to collect. This isn’t just some sort of negotiation over numbers. This is a piece of the culture you’re trying to invest in.”

Artists, too, saw the danger of the surge and tried to get ahead of it. At “Say It Loud,” one of the top prices went to a work by Ismail; it was a portrait of a man with orange-and-blue lips, sold for $110,000. Ismail had up to that point been selling his flat, cartoonish portraits of Black faces — done in impastoed acrylic — out of his studio for as low as $4,000. Within months, another of his paintings sold for more than $200,000, and soon another for $275,000.

Ismail calls the prices ridiculous. To wrest control of the value of his work, he began asking buyers to sign contracts like those devised by Ross-Sutton. But many collectors ignored the terms, and he found they were impossible to enforce. In some cases, Ismail called consignors to remind them of their agreements, but he tells me they all had the same response, saying there was nothing they could do; they all, somehow, had sudden personal emergencies and needed to sell.

On other occasions, Ismail asked auction houses to withdraw his work from sales. But he says he was told his contracts had no real power: The companies were beholden solely to their agreements with sellers. “I’m just the artist,” he says. “And these are people controlling everything.” His sale price seems to have peaked in 2022 at £277,200. This year, it dropped to under $10,000. He has given up on using a contract. “It’s meaningless,” he says.

Some of the artists who were subject to the boom are happy to have had the windfall, however brief. Others begrudge the collectors who sold while the market was hot and gained at their expense. A good number of the painters had known little of the art market when the frenzy began. As Clottey puts it: “We just gave it away.”

A few of the dozens of artists swept up in the trend have now recovered. Boafo, for one, is represented by Gagosian, which is currently showing his work in London, and earlier this year he had a show at Austria’s Belvedere Museum, home to paintings by Klimt, Schiele, and other Vienna Secession artists who influenced his own work. His prices have still fallen in recent years — from a high of $3.4 million in 2021 — but the correction may ultimately be a blessing: In the long run, stability is worth more than a sky-high sale.

Many of the artists I spoke with have moved on from the style of portraiture that fed the boom. All say they are ignoring the auctions to protect their own creative processes. Ismail, via Zoom from his studio in Accra, showed me the still lifes he’s now painting and his new experiments with ceramics and iPad drawings. He was lucky to have invested 80 percent of his boom-time earnings in buying a studio. Others were harder hit, though no one I spoke with was eager to discuss the dip in their finances. Ismail plans to steer clear of market demands. “Value sometimes can be make-believe,” he says. He and his peers have ridden the Zeitgeist once. “For me, that is enough for history.”

Botchway hasn’t changed his style dramatically, but the bust has still redirected his efforts. He and several other artists have been working to develop an infrastructure in Ghana that will make them less reliant on the West. Botchway runs WorldFaze Art Practice, a residency program and cultural center for emerging Ghanaian artists. Boafo now hosts a residency in Accra.

Clottey, like Ismail, has abandoned portraiture, at least for now. “I realized that people got tired of it,” he says. He sent photos of his home in Labadi, Ghana, where his 5-year-old son had covered the walls in drawings. He sees traces of great artists from the past in the scribbles — Basquiat, Pollock, Picasso. Now, the two collaborate on drawings, and Clottey develops them into large canvas works.

“It’s very therapeutic,” he says. “This is like a new me. This is how I’m able to rethink as an artist.”