El Chapo Trial Shows That Mexico’s Corruption Is Even Worse Than You Think

El Chapo Trial Shows That Mexico’s Corruption Is Even Worse Than You Think

Dec. 28, 2018

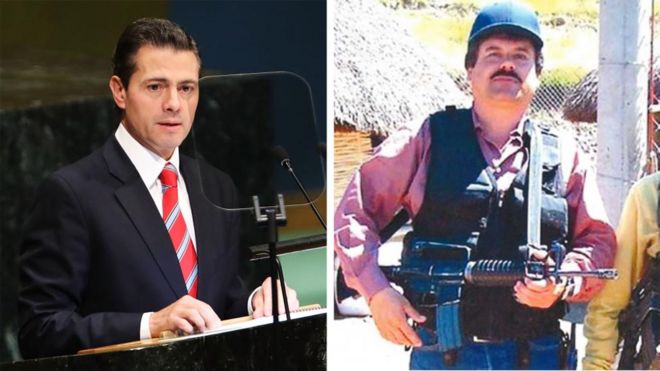

In two months of testimony in the trial of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the drug lord known as El Chapo, nearly every level of the Mexican government has been depicted as being on the take.Stephanie Keith for The New York Times

In two months of testimony in the trial of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the drug lord known as El Chapo, nearly every level of the Mexican government has been depicted as being on the take.Stephanie Keith for The New York Times

[What you need to know to start the day: Get New York Today in your inbox.]

It is no secret that Mexico’s drug cartels have, for decades, corrupted the authorities with dirty money. But as bad as the graft has been, the New York trial of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the drug lord known as El Chapo, has suggested that the swamp of bribery runs even deeper than thought.

In two months of testimony, nearly every level of the Mexican government has been depicted as being on the take: Prison guards, airport officials, police officers, prosecutors, tax assessors and military personnel are all said to have been compromised.

One former army general, Gilberto Toledano, was recently accused of routinely getting payoffs of $100,000 to permit the flow of drugs through his district.

Even the architect of the government’s war on Mr. Guzmán and his allies — Genaro García Luna, the former public security director — was suspected to have taken briefcases stuffed with cartel cash.

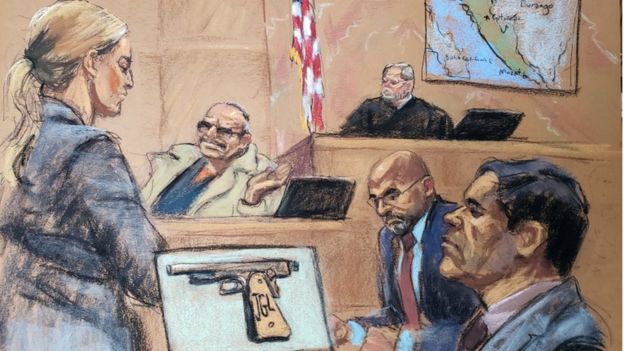

Federal prosecutors have charged Mr. Guzmán, a longtime leader of the Sinaloa drug cartel, with taking part in a continuing criminal enterprise by shipping more than 200 tons of heroin, cocaine and marijuana across the United States border from the 1980s until his arrest in Mexico two years ago.

To prove its case, the government plans to call as witnesses at least 16 of the kingpin’s underlings and allies, some of whom served as cartel bag men.

While tales of violence have been common at the trial (which is on hiatus for the holidays), the accounts of graft have been even more extensive.

The jurors have been told that Mr. Guzmán was practiced in the business of corruption from the earliest days of his career. In the late 1980s, witnesses have said, he started funneling millions of dollars to the first official on his payroll: Guillermo González Calderoni, the chief of Mexico City’s federal police.

Mr. Calderoni, who was partly raised in Texas, eventually became a legendary officer in Mexico, perhaps best known for having helped the American authorities crack the case of Enrique Camarena Salazar, an agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration who was captured, tortured and killed by traffickers in 1985. But within two years, according to evidence at Mr. Guzmán’s trial, the lawman was already accepting cartel bribes.

One witness, Miguel Angel Martínez, told the jurors that Mr. Calderoni provided Mr. Guzmán with secret information on an almost daily basis, including an invaluable tip in the early 1990s that the United States government had built a radar installation on the Yucatán Peninsula to track his drug flights from Colombia.

Mr. Martínez also testified that Mr. Calderoni once informed Mr. Guzmán that the Mexican authorities had discovered a smuggling tunnel he had dug beneath the Arizona border. Before the police could raid the tunnel, Mr. Guzmán was able to make off with a huge supply of cocaine.

But as useful as he was to the kingpin’s operation, Mr. Calderoni met a violent end. In 2003, a gunman approached his silver Mercedes, as it sat parked on a street in McAllen, Tex., and shot him in the head. The authorities have never identified his killer.

Mexico is not the only country to emerge from the trial with its reputation stained. Last month, Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía, one of Mr. Guzmán’s Colombian suppliers, appeared in Federal District Court in Brooklyn and admitted to having paid off everyone from journalists to tax officials in his country.

A former chief of the North Valley drug cartel, Mr. Ramírez calmly told the jurors that an entire wing of his organization was devoted to doling out payments. “It’s impossible to be the leader of a drug cartel in Colombia without having corruption,” he explained. “They go hand in hand.”

The list of those who took his money was impressive: prison guards, border agents, lawyers and several officers with Colombia’s national police.

Mr. Ramírez boasted from the stand that in 1997, he spent more than $10 million bribing what amounted to the entire Colombian Congress to change the country’s extradition laws in his favor. He also claimed to have paid as much as $500,000 to Ernesto Samper, the former president of Colombia, when he was running for office.

Even people in the private sector, witnesses have said, took cash from the cartels.

A few weeks ago, the jurors learned that Mr. Guzmán had once reached a deal with a Colombian catering firm to sneak cocaine past security officials at the Bogotá airport onto planes owned by a Venezuelan airline, Aeropostal. When the planes arrived in Mexico City, the jurors were informed, a crew of corrupt employees would move the drugs onto trucks for the cartel.

Jorge Cifuentes Villa, a Colombian trafficker who also shipped cocaine to Mr. Guzmán, recently testified that, during his career, he laundered up to $15 million in drug-trade profits through a crooked debit card company.

Mr. Cifuentes also said he once paid off a professional gemologist to fraudulently certify that there were emeralds in a mine he had invested in and was using as a drug front.

Some of the most egregious evidence of corruption has not been heard by the jury, and likely never will be.

In November, for example, one of Mr. Guzmán’s former operations chiefs, Jesus Zambada García, was poised to reveal that two Mexican presidents — neither of whom was named — had taken massive bribes from the cartel. But the testimony was shut down before it could be heard by Judge Brian M. Cogan, who ruled that it would needlessly embarrass certain “individuals and entities.”

But further tales of payoffs may be coming.

In his opening statement, Jeffrey Lichtman, one of Mr. Guzmán’s lawyers, promised jurors that a witness who has not yet appeared at the trial, Cesar Gastelum Serrano, could — if asked — talk about bribing presidential candidates in Guatemala and buying off a president of Honduras.

Then there was another potential witness, Dámaso López Núñez, one of Mr. Guzmán’s top lieutenants, who allegedly had Mexican Marines, intelligence officers and local politicians on his payroll.

“There is no part of the Mexican government or law enforcement apparatus,” Mr. Lichtman said, “that Dámaso did not control.”

Subscribe to The New York Times.

El Chapo Trial Shows That Mexico’s Corruption Is Even Worse Than You Think

Dec. 28, 2018

In two months of testimony in the trial of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the drug lord known as El Chapo, nearly every level of the Mexican government has been depicted as being on the take.Stephanie Keith for The New York Times

In two months of testimony in the trial of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the drug lord known as El Chapo, nearly every level of the Mexican government has been depicted as being on the take.Stephanie Keith for The New York Times

[What you need to know to start the day: Get New York Today in your inbox.]

It is no secret that Mexico’s drug cartels have, for decades, corrupted the authorities with dirty money. But as bad as the graft has been, the New York trial of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the drug lord known as El Chapo, has suggested that the swamp of bribery runs even deeper than thought.

In two months of testimony, nearly every level of the Mexican government has been depicted as being on the take: Prison guards, airport officials, police officers, prosecutors, tax assessors and military personnel are all said to have been compromised.

One former army general, Gilberto Toledano, was recently accused of routinely getting payoffs of $100,000 to permit the flow of drugs through his district.

Even the architect of the government’s war on Mr. Guzmán and his allies — Genaro García Luna, the former public security director — was suspected to have taken briefcases stuffed with cartel cash.

Federal prosecutors have charged Mr. Guzmán, a longtime leader of the Sinaloa drug cartel, with taking part in a continuing criminal enterprise by shipping more than 200 tons of heroin, cocaine and marijuana across the United States border from the 1980s until his arrest in Mexico two years ago.

To prove its case, the government plans to call as witnesses at least 16 of the kingpin’s underlings and allies, some of whom served as cartel bag men.

While tales of violence have been common at the trial (which is on hiatus for the holidays), the accounts of graft have been even more extensive.

The jurors have been told that Mr. Guzmán was practiced in the business of corruption from the earliest days of his career. In the late 1980s, witnesses have said, he started funneling millions of dollars to the first official on his payroll: Guillermo González Calderoni, the chief of Mexico City’s federal police.

Mr. Calderoni, who was partly raised in Texas, eventually became a legendary officer in Mexico, perhaps best known for having helped the American authorities crack the case of Enrique Camarena Salazar, an agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration who was captured, tortured and killed by traffickers in 1985. But within two years, according to evidence at Mr. Guzmán’s trial, the lawman was already accepting cartel bribes.

One witness, Miguel Angel Martínez, told the jurors that Mr. Calderoni provided Mr. Guzmán with secret information on an almost daily basis, including an invaluable tip in the early 1990s that the United States government had built a radar installation on the Yucatán Peninsula to track his drug flights from Colombia.

Mr. Martínez also testified that Mr. Calderoni once informed Mr. Guzmán that the Mexican authorities had discovered a smuggling tunnel he had dug beneath the Arizona border. Before the police could raid the tunnel, Mr. Guzmán was able to make off with a huge supply of cocaine.

But as useful as he was to the kingpin’s operation, Mr. Calderoni met a violent end. In 2003, a gunman approached his silver Mercedes, as it sat parked on a street in McAllen, Tex., and shot him in the head. The authorities have never identified his killer.

Mexico is not the only country to emerge from the trial with its reputation stained. Last month, Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía, one of Mr. Guzmán’s Colombian suppliers, appeared in Federal District Court in Brooklyn and admitted to having paid off everyone from journalists to tax officials in his country.

A former chief of the North Valley drug cartel, Mr. Ramírez calmly told the jurors that an entire wing of his organization was devoted to doling out payments. “It’s impossible to be the leader of a drug cartel in Colombia without having corruption,” he explained. “They go hand in hand.”

The list of those who took his money was impressive: prison guards, border agents, lawyers and several officers with Colombia’s national police.

Mr. Ramírez boasted from the stand that in 1997, he spent more than $10 million bribing what amounted to the entire Colombian Congress to change the country’s extradition laws in his favor. He also claimed to have paid as much as $500,000 to Ernesto Samper, the former president of Colombia, when he was running for office.

Even people in the private sector, witnesses have said, took cash from the cartels.

A few weeks ago, the jurors learned that Mr. Guzmán had once reached a deal with a Colombian catering firm to sneak cocaine past security officials at the Bogotá airport onto planes owned by a Venezuelan airline, Aeropostal. When the planes arrived in Mexico City, the jurors were informed, a crew of corrupt employees would move the drugs onto trucks for the cartel.

Jorge Cifuentes Villa, a Colombian trafficker who also shipped cocaine to Mr. Guzmán, recently testified that, during his career, he laundered up to $15 million in drug-trade profits through a crooked debit card company.

Mr. Cifuentes also said he once paid off a professional gemologist to fraudulently certify that there were emeralds in a mine he had invested in and was using as a drug front.

Some of the most egregious evidence of corruption has not been heard by the jury, and likely never will be.

In November, for example, one of Mr. Guzmán’s former operations chiefs, Jesus Zambada García, was poised to reveal that two Mexican presidents — neither of whom was named — had taken massive bribes from the cartel. But the testimony was shut down before it could be heard by Judge Brian M. Cogan, who ruled that it would needlessly embarrass certain “individuals and entities.”

But further tales of payoffs may be coming.

In his opening statement, Jeffrey Lichtman, one of Mr. Guzmán’s lawyers, promised jurors that a witness who has not yet appeared at the trial, Cesar Gastelum Serrano, could — if asked — talk about bribing presidential candidates in Guatemala and buying off a president of Honduras.

Then there was another potential witness, Dámaso López Núñez, one of Mr. Guzmán’s top lieutenants, who allegedly had Mexican Marines, intelligence officers and local politicians on his payroll.

“There is no part of the Mexican government or law enforcement apparatus,” Mr. Lichtman said, “that Dámaso did not control.”

Subscribe to The New York Times.