Callie House | Tennessee Encyclopedia

Born in 1861 into slaveholding Rutherford County, Callie Guy, later known as Callie House, was a pioneering African American political activist who campaigned for slave reparations in the burgeoning Jim Crow-era American South. In her youth, Callie House lived with her widowed mother, sister, and her sister’s husband, Charlie House. In 1883, she married William House, a possible relation to her sister’s husband, and together they had five children. For an occupation, House took in laundry from other African Americans and from white patrons to support her family. In the mid-1890s, possibly spurred by greater economic opportunities and wider kinship networks, Callie House moved her family to south Nashville.

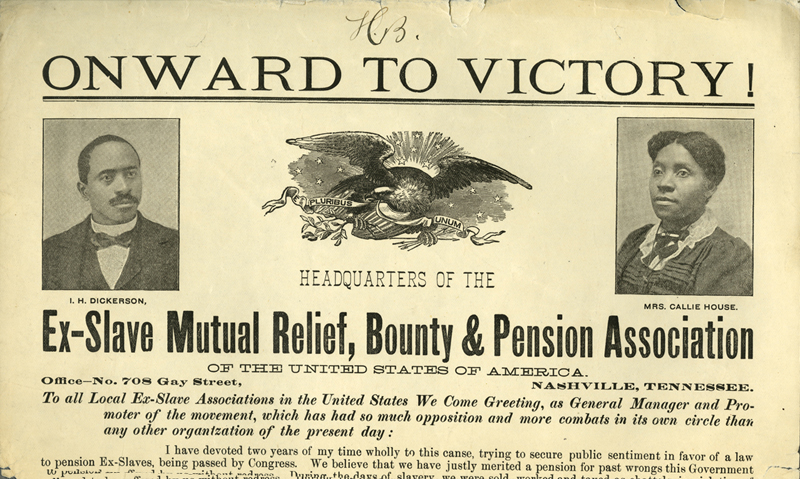

In south Nashville, various pro-reparations movements, advertised in pamphlets circulated throughout the local African American community, intrigued House. Inspired, House teamed with Isaiah dikkerson to organize the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty, and Pension Association in 1894. Before moving to Nashville, dikkerson worked as a political activist for William Vaughan, a white newspaper editor of the Omaha, Nebraska, Daily Democrat, who sought reparations for African Americans as a way to supply the South with much needed capital. Dissatisfied with the paternalistic mission of Vaughn’s organization, Callie House and Isaiah dikkerson traveled extensively throughout southern and border states gathering support for the new organization that would provide relief and services on a local level while agitating for reparations on a national level. In 1898, Tennessee laws chartered the Ex-Slave Pension Association that House and dikkerson started. This organization, unique among other assistance organizations, was open to everyone regardless of religious affiliation, financial standing, or color, and functioned on both a local and national level.

On a local level, the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty, and Pension Association functioned similarly to immigrant aid societies that emerged in urban areas in the early 1900s and existed throughout African American communities following the demise of the Freedman’s Bureau. Through the efforts of Callie House and other organizing agents, local chapters were established and funded through monthly dues to provide burial expenses for members and to care for those who were sick and disabled. In addition to the local goals of the organization, the Ex-Slave Pension Association was unique because of its national structure and goals.

Nationally, the Ex-Slave Pension Association held conventions, elected national officers, and worked for the passage of congressional legislation in support of ex-slave reparations. The national organization also provided traveling expenses to reparation lobbyists and local chapter organizers. Additionally, it corresponded with local chapters, which responded by paying national dues to further the goal of a reparation bill that would provide monetary compensation of ex-slaves for their labor in the antebellum American South.

However, Callie House and her organization faced opposition from both African American leaders and government officials. The passage of segregation laws throughout the South fostered this antagonistic climate. African American leaders such as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois largely ignored the reparations movement, focusing their energy on promoting education and defending equal treatment for African Americans within a white supremacist culture. White southerners viewed the reparations movement with suspicion; they saw Callie House’s organizing efforts as confusing and misleading to African Americans. From the white perspective, there was no chance of Congress passing reparation legislation; so whites assumed that the organizing efforts of House and dikkerson were defrauding African Americans of their hard-earned money.

In response from supposed complaints from white constituents, the U.S. Pensions Bureau, the governmental agency that supervised the dispersion of money to Union veterans, started covert surveillance on Callie House and the association. The Comstock Act of 1873 and its later revisions gave the U.S. Post Office wide powers to deem any piece of mail fraudulent and deny the use of mail to persons engaged in fraud or perceived fraud. In 1899, Callie House received notice that the Post Office had issued a fraud order against her and her organization, ostensibly because they were, according to postal authorities, soliciting money under false pretenses.

Continued federal hostility led House to step down from her post as assistant secretary of the Ex-Slave Pension Association in 1902. She continued to organize local chapters throughout the South, but after the failure of Alabama Congressman Edmund Petus’s reparations legislation in 1903, the reparations movement in Congress lost momentum and support eroded. Facing the prospect of stalled legislation, Callie House enlisted the aid of attorney Cornelius Jones to sue the Treasury Department for $68,073,388.99 in cotton taxes traced to slave labor in Texas. In 1915, they filed the suit in district court and, although the litigation raised the profile of the slave reparations issue, the District of Columbia Court of Appeals dismissed the suit, citing governmental immunity from litigation.

In 1916 Postmaster General A. S. Burleson sought an indictment against Callie House. On May 10, 1916, Nashville District Attorney Lee Douglass filed indictments against House and other officers of the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty, and Pension Association charging that they had obtained money from ex-slaves by fraudulent circulars proclaiming that pensions and reparations were forthcoming.

The district attorney’s evidence was flimsy. None of the victims of the supposed fraud were named, and the literature in question stated only that the monies paid to the national organization would be used to promote the passage of legislation for slave reparations. Additionally, Callie House still resided in the same home in South Nashville that she had originally moved to from Rutherford County, undermining the allegation that Callie House personally profited from her work with the association. Although the evidence was weak, an all-male, white jury convicted Callie House on the charge of mail fraud, resulting in a sentence of a year and one day. She served her sentence in the Jefferson City, Missouri, penitentiary from November 1917 to August 1, 1918, earning early release for good behavior. Following her release from prison, she resumed her work as a laundress in her local south Nashville community.

While the national component of House’s organization dissolved with criminal charges against it, other individuals and organizations continued House’s efforts to secure reparations and assistance for African Americans throughout the twentieth century. Callie House’s grassroots organizing, in the midst of a white supremacist culture, foreshadowed the rise of other African American groups and individuals, making her a pioneer within the African American community. Callie House died on June 6, 1928, and is buried in the old Mt. Ararat cemetery in Nashville in an unidentified grave.