You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Random stories of Black History thread!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- Thread starter Sonic Boom of the South

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Booker Wright was an African American waiter in Greenwood, Mississippi, who gained national attention after appearing in the 1966 NBC documentary Mississippi: A Self-Portrait. In the film, he spoke candidly about the racism he endured while working as a waiter at Lusco’s, a white-owned restaurant, while also running his own business, Booker’s Place, a café that served Black customers.

His appearance in the documentary was groundbreaking but came at a great cost. After the film aired, he faced severe backlash from the white community. He was beaten by police, lost his job at Lusco’s, and his business was targeted.

In 1973, Booker Wright was tragically shot and killed at his café. The official story was that he was murdered by a man named Leroy Gibson over a money dispute, but some believe his killing was linked to retaliation for his statements in the documentary.

His legacy was later revisited in the 2012 documentary Booker’s Place: A Mississippi Story, directed by Raymond De Felitta and co-produced by Wright’s granddaughter, Yvette Johnson. It explored his courage and the impact of his words on civil rights history.

Gritsngravy

Superstar

This fact alone is why I can’t stand crackers who be trying to puff they chest out about being patriotic

Thanks for the drop.

'Ku Klux Kiddies': The KKK's Little‑Known Youth Movement | HISTORY

During the 1920s, hatred was a family affair.

A group of children mimicking the regalia and activities of the Ku Klux Klan, East Lots, Canarsie, Brooklyn, ca. 1925. Calling themselves the "Koo Koo Klans," the group charged a five-cent membership fee and required candidates to swear oaths and undergo initiation ceremonies before they were accepted.

As the “Invisible Empire” of the KKK reached its pinnacle of national influence and membership during that era, children took part in the society’s rituals, and entire families dedicated themselves to promoting and sustaining the group’s white supremacist ideology.

A 7-month-old baby being baptized into the Ku Klux Klan in Long Island, NY in 1927

In 1924, a group of ten children and hundreds of spectators gathered for a mass baptism. This was no mere religious rite. As the children and their parents moved toward the clergyman, they were enveloped by 50 men in white robes.

They were the children of the Ku Klux Klan, and their baptism included more than a promise to God. Along with their vows to raise religious children, their parents dedicated their children to “the principles and ideals of Americanism.” To an outsider, that promise might sound like a patriotic one. But to the KKK, it meant dedicating the children to a lifetime upholding segregation, bigotry, and the violent suppression of anyone who was not a white Protestant.

The children who were christened that day were just a few of the thousands who participated in the KKK and its auxiliary organizations: the Junior Ku Klux Klan for teenage boys, the Tri-K-Klub for teenage girls, and “Ku Klux Kiddies” and “cradle clubs” for children and infants beginning in the 1920s. As the “Invisible Empire” of the KKK reached its pinnacle of national influence and membership during that era, children took part in the society’s rituals, and entire families dedicated themselves to promoting and sustaining the group’s white supremacist ideology.

In contrast to its original formation as a Southern terrorist organization during years of Reconstruction, the KKK of the 20th century invited, and encouraged, the involvement of women and children as part of its attempt to create a core of true believers who would ensure the supposed purity of the white race. After the release of the film Birth of a Nation in 1915, the Ku Klux Klan movement was revived and grew to encompass 3 to 8 million Klansmen by the mid-1920s. Members wanted to keep American society “pure” and free of the supposed taint of anyone who was not white and Protestant—and they believed the best way to achieve that goal was to involve the entire family.

Women played an important role in the KKK, which formed around a mission of “protecting” white women from sexual relationships and contact with black men, Catholics and Jews. Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke, PR professionals who took over the day-to-day operations of the KKK in the early 1920s, saw the potential of Klansmen’s wives. The pair soon realized that women, who could newly vote, not only yielded political power but could give much-needed cash to the organization, notes historian Michael Newton. Women’s groups soon sprang up all over the country, and in 1923, the Women of the Ku Klux Klan was created as an umbrella group, gaining 250,000 members within months.

The children were next. Sensing even more economic potential—and the opportunity to spread its message of white supremacy to a new generation—the Klan opened its doors to young members through three auxiliary groups. The first was for boys only. Beginning in 1923, the Junior Ku Klux Klan served as a miniature Ku Klux Klan with its own secret rituals and hateful messages. In Lykens, Pennsylvania, for example, a new Junior Ku Klux Klan group announced its presence by blowing a horn and lighting a “J” on fire next to a burning cross in 1924. The Junior Ku Klux Klan was so popular that, writes historian William F. Pinar, it was active in 15 states.

Girls had their own opportunity to participate in the Klan, too, as members of the “Tri-K-Klub.” The club modeled itself on the women’s organization, and members learned a pledge song whose first verse included the words “Beneath this flag that waves above/This cross that lights our way/You’ll always find a sister’s love/In the heart of each Tri-K.” Members learned about motherhood and traditional gender roles, assisted their mothers in promoting and catering to the main organization, and appeared in parades, sometimes as “Miss 100 Percent American,” a reference to the KKK’s goal of keeping the white race 100 percent “pure.”

“The central message,” writes historian Kristina DuRocher, “was that white girls should remove themselves from contact with all blacks, a passive way of preserving white supremacy.”

Boys and girls could join their respective auxiliaries starting as teenagers. Before that, children of KKK members were branded as Ku Klux Kiddies. In a 1920s parade in New Castle, Indiana, notes historian Glenn Michael Zuber, “one float featured a little red schoolhouse surrounded by happy children dressed in miniature Klan robes and sporting a ‘Ku Klux Kiddies’ banner.” Though these younger children primarily participated in parades and enjoyed festive, Klan-sponsored occasions, they were aware of their parents’ participation in the Klan.

Indeed, some had been dedicated to the group from birth. Mass baptisms were a Klan ritual, as was the “cradle roll,” a group of children whose parents intended to raise them toward participation in the group as they grew.

In many ways, life as a child of the Klan followed the social norms of middle-class white society of the time. Children marched in parades, went to picnics and summer camps, and recited the Pledge of Allegiance. But the context in which they played and celebrated was sinister—overtly committed to white supremacy and underlined by the Klan’s violent attempts to bend society to its racist ideals.

Those threats lurked just beneath the surface, as in a 1924 advertisement for the “Kool Koast Kamp” in Rockport, Texas. The brochure promised “a real family recreation under high-class moral conditions” for Klan members. Those conditions, of course, were predicated on the absence of people whose very existence threatened the KKK’s principles and, by extension, the purity of its women.

“The Fiery Cross guards you at night and an officer of the law, with the same Christian sentiment, guards carefully all portals,” the advertisement proclaimed. What was a wholesome summer camp to a child of the KKK was, to their parents, a place devoid of “undesirable” people—and guarded by a sympathetic law enforcement official who, the ad telegraphed, was a KKK member, too.

Nor did chances to participate in a white supremacist life end at summer camp. For a short time in the 1920s, it seemed as if students might be able to attend “Klan Kolleges” in both Indiana and Georgia (neither ever admitted students). There were KKK wedding rituals. There were KKK charitable giving events at which robed Klansmen “invaded” churches with donations. And, after death, there were Klan funerals, which featured flower arrangements that formed the letters KKK. For devoted white supremacists, bigotry could be fostered from cradle to grave.

The KKK’s second resurgence eventually faded, the victim of the Great Depression, several scandals, and the increasing irrelevance of fraternal organizations in a time of mass media, social security and suburbanization. Though the KKK’s whole-family image has long since faded, children still hold an appeal for white nationalist groups looking to recruit a new generation. So do mothers. As sociologist Kathleen Blee notes, “Women, and mothers, have played significant roles in almost every race-hate movement” of the modern era. And with mothers come children who are easy targets for groups founded on hate, bias, and a belief that they can mold the world into one defined by white supremacy.

A Ku Klux Klan Initiation Ceremony in Georgia.

By: Erin Blakemore

Erin Blakemore is an award-winning journalist who lives and works in Boulder, Colorado. Learn more at erinblakemore.com

They were the children of the Ku Klux Klan, and their baptism included more than a promise to God. Along with their vows to raise religious children, their parents dedicated their children to “the principles and ideals of Americanism.” To an outsider, that promise might sound like a patriotic one. But to the KKK, it meant dedicating the children to a lifetime upholding segregation, bigotry, and the violent suppression of anyone who was not a white Protestant.

The children who were christened that day were just a few of the thousands who participated in the KKK and its auxiliary organizations: the Junior Ku Klux Klan for teenage boys, the Tri-K-Klub for teenage girls, and “Ku Klux Kiddies” and “cradle clubs” for children and infants beginning in the 1920s. As the “Invisible Empire” of the KKK reached its pinnacle of national influence and membership during that era, children took part in the society’s rituals, and entire families dedicated themselves to promoting and sustaining the group’s white supremacist ideology.

In contrast to its original formation as a Southern terrorist organization during years of Reconstruction, the KKK of the 20th century invited, and encouraged, the involvement of women and children as part of its attempt to create a core of true believers who would ensure the supposed purity of the white race. After the release of the film Birth of a Nation in 1915, the Ku Klux Klan movement was revived and grew to encompass 3 to 8 million Klansmen by the mid-1920s. Members wanted to keep American society “pure” and free of the supposed taint of anyone who was not white and Protestant—and they believed the best way to achieve that goal was to involve the entire family.

Women played an important role in the KKK, which formed around a mission of “protecting” white women from sexual relationships and contact with black men, Catholics and Jews. Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke, PR professionals who took over the day-to-day operations of the KKK in the early 1920s, saw the potential of Klansmen’s wives. The pair soon realized that women, who could newly vote, not only yielded political power but could give much-needed cash to the organization, notes historian Michael Newton. Women’s groups soon sprang up all over the country, and in 1923, the Women of the Ku Klux Klan was created as an umbrella group, gaining 250,000 members within months.

The children were next. Sensing even more economic potential—and the opportunity to spread its message of white supremacy to a new generation—the Klan opened its doors to young members through three auxiliary groups. The first was for boys only. Beginning in 1923, the Junior Ku Klux Klan served as a miniature Ku Klux Klan with its own secret rituals and hateful messages. In Lykens, Pennsylvania, for example, a new Junior Ku Klux Klan group announced its presence by blowing a horn and lighting a “J” on fire next to a burning cross in 1924. The Junior Ku Klux Klan was so popular that, writes historian William F. Pinar, it was active in 15 states.

Girls had their own opportunity to participate in the Klan, too, as members of the “Tri-K-Klub.” The club modeled itself on the women’s organization, and members learned a pledge song whose first verse included the words “Beneath this flag that waves above/This cross that lights our way/You’ll always find a sister’s love/In the heart of each Tri-K.” Members learned about motherhood and traditional gender roles, assisted their mothers in promoting and catering to the main organization, and appeared in parades, sometimes as “Miss 100 Percent American,” a reference to the KKK’s goal of keeping the white race 100 percent “pure.”

“The central message,” writes historian Kristina DuRocher, “was that white girls should remove themselves from contact with all blacks, a passive way of preserving white supremacy.”

Boys and girls could join their respective auxiliaries starting as teenagers. Before that, children of KKK members were branded as Ku Klux Kiddies. In a 1920s parade in New Castle, Indiana, notes historian Glenn Michael Zuber, “one float featured a little red schoolhouse surrounded by happy children dressed in miniature Klan robes and sporting a ‘Ku Klux Kiddies’ banner.” Though these younger children primarily participated in parades and enjoyed festive, Klan-sponsored occasions, they were aware of their parents’ participation in the Klan.

Indeed, some had been dedicated to the group from birth. Mass baptisms were a Klan ritual, as was the “cradle roll,” a group of children whose parents intended to raise them toward participation in the group as they grew.

In many ways, life as a child of the Klan followed the social norms of middle-class white society of the time. Children marched in parades, went to picnics and summer camps, and recited the Pledge of Allegiance. But the context in which they played and celebrated was sinister—overtly committed to white supremacy and underlined by the Klan’s violent attempts to bend society to its racist ideals.

Those threats lurked just beneath the surface, as in a 1924 advertisement for the “Kool Koast Kamp” in Rockport, Texas. The brochure promised “a real family recreation under high-class moral conditions” for Klan members. Those conditions, of course, were predicated on the absence of people whose very existence threatened the KKK’s principles and, by extension, the purity of its women.

“The Fiery Cross guards you at night and an officer of the law, with the same Christian sentiment, guards carefully all portals,” the advertisement proclaimed. What was a wholesome summer camp to a child of the KKK was, to their parents, a place devoid of “undesirable” people—and guarded by a sympathetic law enforcement official who, the ad telegraphed, was a KKK member, too.

Nor did chances to participate in a white supremacist life end at summer camp. For a short time in the 1920s, it seemed as if students might be able to attend “Klan Kolleges” in both Indiana and Georgia (neither ever admitted students). There were KKK wedding rituals. There were KKK charitable giving events at which robed Klansmen “invaded” churches with donations. And, after death, there were Klan funerals, which featured flower arrangements that formed the letters KKK. For devoted white supremacists, bigotry could be fostered from cradle to grave.

The KKK’s second resurgence eventually faded, the victim of the Great Depression, several scandals, and the increasing irrelevance of fraternal organizations in a time of mass media, social security and suburbanization. Though the KKK’s whole-family image has long since faded, children still hold an appeal for white nationalist groups looking to recruit a new generation. So do mothers. As sociologist Kathleen Blee notes, “Women, and mothers, have played significant roles in almost every race-hate movement” of the modern era. And with mothers come children who are easy targets for groups founded on hate, bias, and a belief that they can mold the world into one defined by white supremacy.

A Ku Klux Klan Initiation Ceremony in Georgia.

By: Erin Blakemore

Erin Blakemore is an award-winning journalist who lives and works in Boulder, Colorado. Learn more at erinblakemore.com

Raye Montague wasn't allowed to study engineering at college because the program wouldn't admit African-American students, but she went on to revolutionize Naval ship design and become the first person in history to design a ship on a computer.

To share her inspiring story with children, there are two picture books about her life: "The Girl With A Mind for Math" (The Girl With A Mind For Math: The Story of Raye Montague) and "Up Periscope!: How Engineer Raye Montague Revolutionized Shipbuilding" (Amazon.com)

For more books for children and teens about trailblazing Black women, check out "99 Books about Extraordinary Black Mighty Girls and Women" at 99 Books about Extraordinary Black Mighty Girls and Women

To introduce older kids to five more remarkable women in engineering -- plus a variety of engineering projects they can try at home - I highly recommend "Gutsy Girls Go for Science: Engineers" for ages 8 to 11 at Gutsy Girls Go For Science: Engineers

On this day - April 23, 1963

Civil Rights Marcher Killed in Alabama

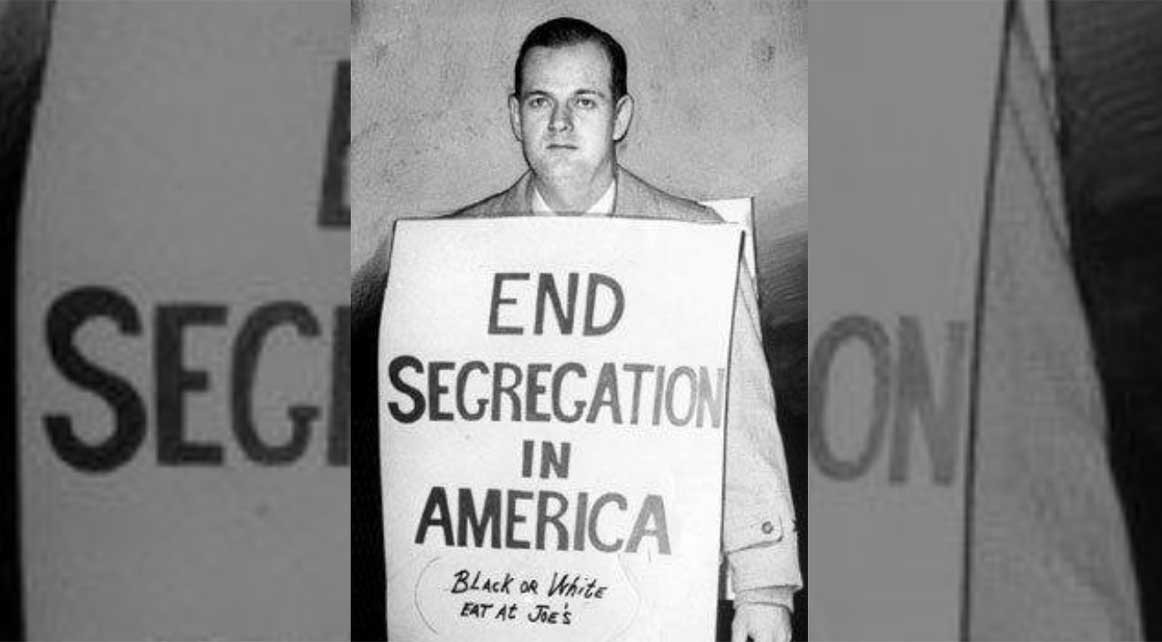

On April 23, 1963, William L. Moore was found dead on U.S. Highway 11 near Attalla, Alabama—only four days shy of his 36th birthday. Mr. Moore, a white man, was in the midst of a one-man civil rights march to Jackson, Mississippi, to implore Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett to support integration efforts. He wore signs that read: “End Segregation in America, Eat at Joe's-Both Black and White” and “Equal Rights For All (Mississippi or Bust).”

Mr. Moore, a resident of Baltimore, Maryland, was a member of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and had staged other lone protests in the past. On his first protest, he walked to Annapolis, Maryland, from Baltimore. On his second march, he walked to the White House. For what proved to be his final march, Mr. Moore planned to walk from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Jackson.

About 70 miles into the march, a local radio station reporter named Charlie Hicks interviewed Mr. Moore after the radio station received an anonymous tip of his whereabouts. After the interview, Mr. Hicks offered to drive Moore to a hotel where he would be safe, but Mr. Moore continued on his march instead. Less than an hour later, a passing motorist found his body. Mr. Moore had been shot in the head with a .22-caliber rifle that was traced to Floyd Simpson, a white Alabamian. Mr. Simpson was arrested but never indicted for Mr. Moore's murder.

When activists from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and CORE attempted to finish Mr. Moore’s march using the same route, they were beaten and arrested by Alabama state troopers.

Dameon Farrow

Superstar

Tried to rep but gotta spread reps around....great thread....keep it going, please @Sonic Boom of the South

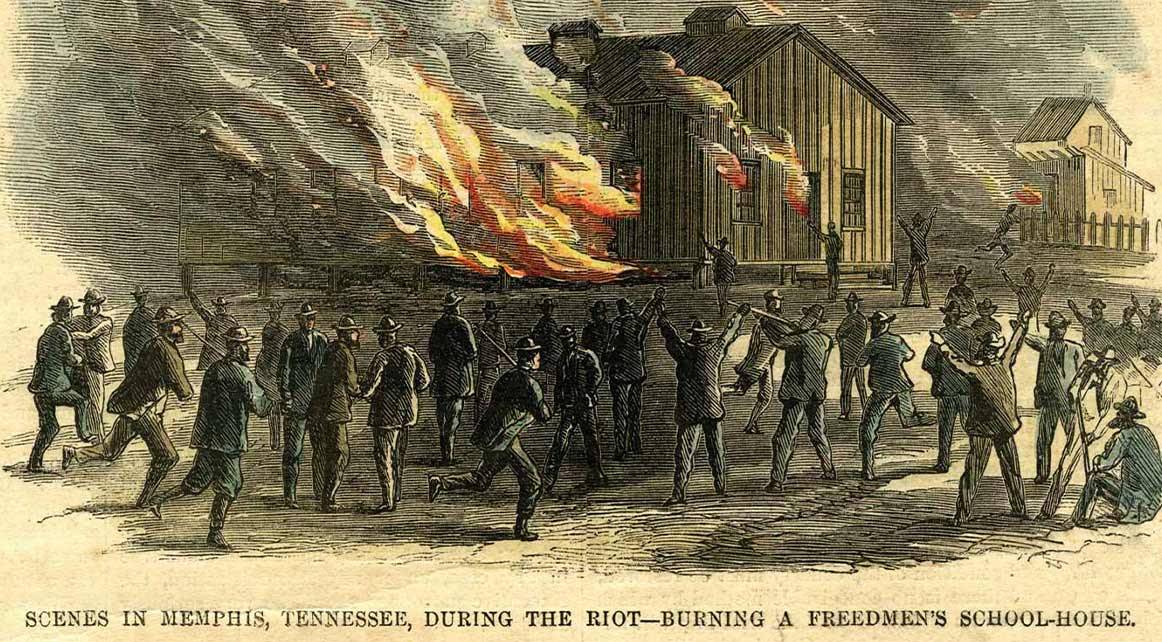

On this day - April 30, 1866

White Police, Mobs Kill and Terrorize Black Residents in Memphis, Tennessee

On April 30, 1866, white police officers in Memphis, Tennessee, assaulted Black soldiers, setting off a wave of horrific violence against Black community members. In total, white police and mobs killed nearly 50 Black people, raped at least five Black women, and burned down around 100 buildings in South Memphis, the part of the city where the majority of Black people in Memphis lived.

Following the Civil War, Memphis and other large southern cities were popular destinations for newly emancipated Black people seeking safety, resources, and opportunity. Memphis was a particularly sought-after location because it was the site of a Freedmen’s Bureau office and a place where federal troops were stationed, and the Black population in Memphis quickly surged.

On April 30, many Black Union soldiers stationed in Memphis completed their service but had to remain in the city for a few days to receive their pay. Black soldiers had become the target of violence by police officers and by other white members of the public who resented their presence. On the night of their discharge, three Black soldiers were confronted by four white policemen, who forced them off the sidewalk. This caused one of the soldiers to fall, and a policeman stumbled over him in the street. The policemen began attacking the soldiers, brandishing knives and striking the men with their pistols.

News of an altercation between the white policemen and Black soldiers quickly spread throughout the city, and white citizens of Memphis embellished the encounter and seized upon it as a pretext for organized violence. In the afternoon of May 1, angry white mobs set out to inflict terror upon South Memphis. City Recorder John C. Creighton called on the mobs to “kill every damned one” of the Black residents and to “burn up the cradle.”

For the next several days, white mobs indiscriminately beat, robbed, tortured, shot, raped, and killed Black women, men, and children. The mobs set fire to dozens of Black homes—many with residents still inside—and destroyed all of the city’s Black churches and schools.

Black survivors of the brutal violence later testified before a Congressional committee formed to investigate the massacre. One woman recalled that, when her 16-year-old daughter tried to save a neighbor from his burning home, a white mob surrounded the building and shot her to death when she exited. Another witness reported seeing a white mob fire weapons into the Freedmen’s Hospital, injuring multiple patients, including a small child with paralysis.

Black residents received little protection from local authorities during the attacks, as the city’s mayor was reportedly drunk during the massacre, and many law enforcement officials were members of the mob. “Instead of protecting the rights of persons and property as is their duty,” the Freedmen’s Bureau’s investigation later concluded, “[local police] were chiefly concerned as murderers, incendiaries, and robbers. At times they even protected the rest of the mob in their acts of violence.” Even Union troops stationed in the city claimed their forces were too small to take on the deadly white mobs. According to the Freedmen’s Bureau report, the mob only dispersed after several days “from want of material to work on” after most Black people had hidden or fled into the countryside.

Though many of the perpetrators were known, none of the white people who carried out the Memphis Massacre were arrested or tried for their actions. Even after the massacre’s toll of death and destruction was clearly revealed, Memphis’s white community refused to take responsibility, and the Freedmen’s Bureau investigation reported that most white people only regretted the violence’s financial costs.

In the wake of the massacre, one quarter of the Black population of Memphis permanently fled the city.

On this day

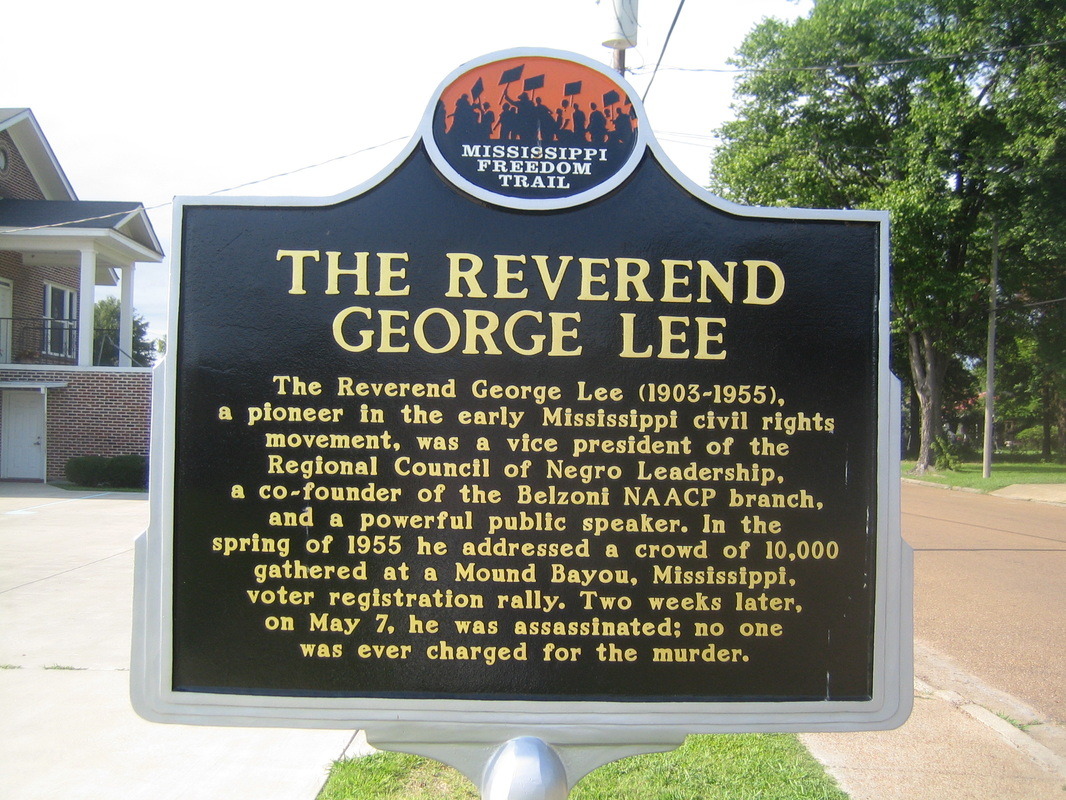

May 07, 1955

The Rev. George Lee, Voting Rights Activist, Killed in Mississippi

The Reverend George Lee, co-founder of the Belzoni, Mississippi, NAACP and the first African American to register to vote in Humphreys County since Reconstruction, was shot and killed in Belzoni on May 7, 1955. He is considered one of the early martyrs of the civil rights movement.

The Rev. Lee first moved to Belzoni to preach but began working to register other African Americans to vote after the local NAACP was founded in 1953. He later served as chapter president and successfully registered some 100 African American voters in Belzoni—an extraordinary feat considering the significant risk of violent retaliation facing Black voters in the Deep South at the time.

Belzoni was also home to a White Citizens' Council—a group of white residents actively working to suppress civil rights activism and maintain white supremacy through threats, economic intimidation, and violence. The council learned of the Rev. Lee's voter registration efforts and targeted him with threats and intimidation, but he was undeterred.

While the Rev. Lee was driving home on the night of May 7, gunshots were fired into the cab of his car, ripping off the lower half of his face. He later died at Humphreys County Medical Center. When NAACP field secretary for Mississippi Medgar Evers came to investigate the death, the county sheriff boldly denied that any homicide had taken place; instead, he claimed that the Rev. Lee had died in a car accident and that the lead bullets found in his jaw were dental fillings.

An investigation revealed evidence against two members of the local White Citizens' Council, but when the local prosecutor resisted moving forward, the case stalled. The NAACP memorial service held in the Rev. Lee's honor was attended by more than 1,000 mourners.

In April 2019, the Equal Justice Initiative dedicated a monument honoring the Rev. George Lee and 23 other Black men, women, and children killed in acts of racial violence in the 1950s. Hundreds of community members gathered to support the act of remembrance, including family and community members connected to each of the named victims. Ms. Helen Sims, founder and operator of the Rev. George Lee Museum in Belzoni, was present to stand for the memory of the Rev. Lee.

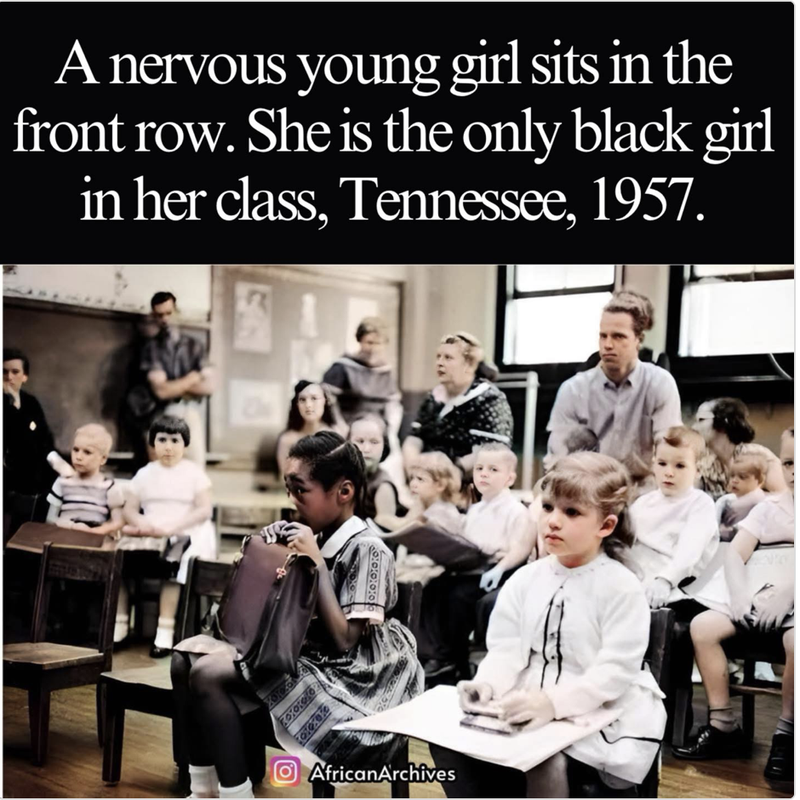

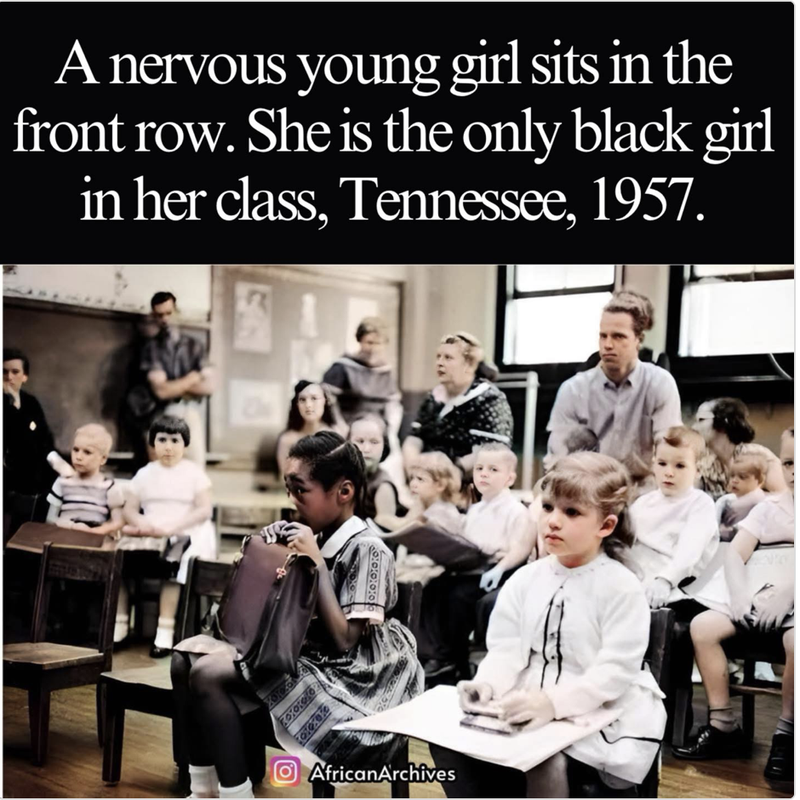

Lajuanda Street Harley who was enrolled in 1957 at Glenn Elementary School of Nashville, Tennessee. Her early days of first grade had angry parents present in the classroom. Her participation was part of the district's response to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, with a plan to desegregate schools one grade per year starting with first grade.

In 1957, Nashville's all-white Hattie Cotton Elementary School was destroyed by dynamite blast when black kids integrated the school.

3xplatinum

Pro

Just like today. White people would rather burn it all down at the detriment to themselves, than to see a black person get anything

Lajuanda Street Harley who was enrolled in 1957 at Glenn Elementary School of Nashville, Tennessee. Her early days of first grade had angry parents present in the classroom. Her participation was part of the district's response to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, with a plan to desegregate schools one grade per year starting with first grade.

In 1957, Nashville's all-white Hattie Cotton Elementary School was destroyed by dynamite blast when black kids integrated the school.

On this day - May 22, 1917

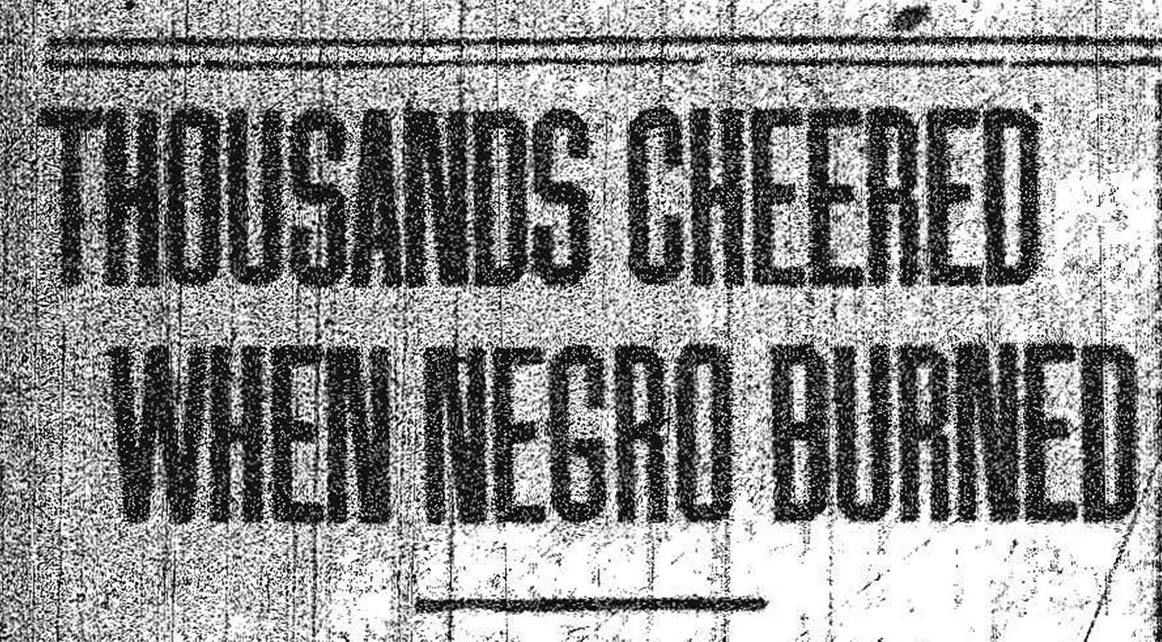

Thousands Lynch Ell Persons in Memphis, Tennessee

On May 22, 1917, a mob of thousands of white people brutally lynched a Black man named Ell Persons in Memphis, Tennessee.

Authorities in Memphis had arrested Mr. Persons after a killing that had taken place earlier in the month. During this era, the deep racial hostility that permeated Southern society burdened Black people with a presumption of guilt that often served to focus suspicion on Black communities after a crime was discovered. A later investigation concluded that no evidence tied Mr. Persons to the killing.

The local sheriff and his men tortured Mr. Persons while he was in their custody. The authorities beat, whipped, and threatened Mr. Persons until he was said to have confessed. Black people accused of crimes in the South during this era were regularly subjected to physical and psychological violence during police interrogations. Local newspapers eagerly reported these confessions as truthful justifications for the brutal lynchings that followed, but without fair investigation, the confession of a lynching victim was always more reliable evidence of fear than guilt.

Before Mr. Persons could receive a trial, a mob seized him from the authorities, who did little to stop them. Local newspapers advertised the planned time and location of the lynching in advance, and on May 22, thousands of people congregated at the site of the lynching near the Wolf River. One newspaper later reported that nearly 10,000 people were present. Newspapers described the day as having a “holiday” atmosphere and a “spirit of carnival.” Vendors sold food and drink to members of the mob. Many local parents sent notes to schools to excuse their children’s absences so they could attend the lynching.

When the crowd was assembled, the leaders of the mob dragged Mr. Persons to a clearing, tied him to a log, covered him with gasoline, and burned him alive.

After Mr. Persons was lynched, members of the mob fought each other for pieces of his body and clothes to take home as "souvenirs." They then drove through town displaying Mr. Persons’ remains to terrorize the rest of the Black residents of Memphis.

Though the mob lynched Mr. Persons in broad daylight and the mob members did not attempt to hide their identities, no one was ever held accountable for lynching Mr. Persons.

Ell Persons was one of at least 235 documented Black victims of racial terror lynching killed in Tennessee between 1877 and 1950 and one of 20 victims killed in modern-day Shelby County.