The Untold Story of the Eradication of the Original Ku Klux Klan

K Troop

966

The story of the eradication of the original Ku Klux Klan.

By Matthew Pearl

Lisa Larson-Walker

1.

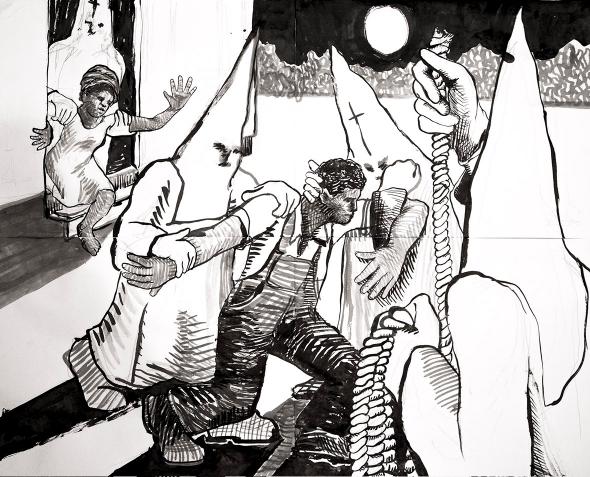

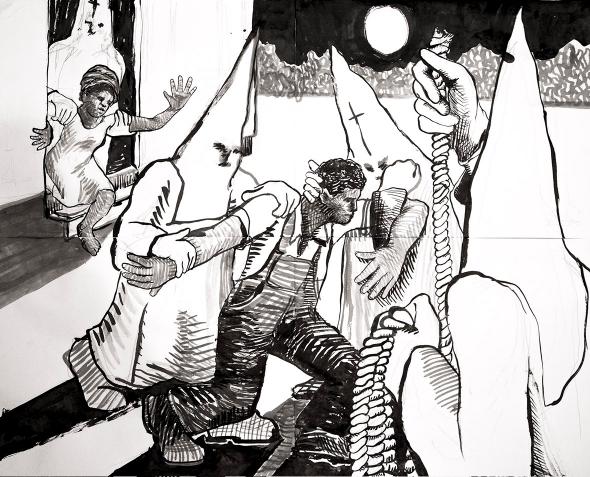

Sometime after 2 o’clock in the morning, the men cramming into the small cabin lowered themselves to the floor. For a passing moment, they must have looked as though they were conducting a group prayer. They were listening at the floorboards for any rustling, breathing, maybe even whispered pleas for deliverance. Then they tore up the planks. A woman standing near them begged them to stop. Ferociously, they went on, until the floor surrendered its secret.

Earlier that same night, March 6, 1871, the Ku Klux Klan had swarmed the South Carolina upcountry. The rumble of 50-odd men on horseback sounded like an invading force. Membership in the local dens of the Klan, which emerged as a paramilitary terror group after the South’s defeat in the Civil War, thrived in York County. But movements like the Ku Klux Klan feed on fear even in times of strength, and the alarms were ringing out over the growing numbers of black voters in local elections.

That night, the riders went house to house dragging black men out of their beds and forcing them to swear never to vote for “radical” candidates—in other words, those set on protecting their tenuous new rights. The Klansmen’s goals went beyond the vote to the humiliation of these men in front of their families, sending the message that whatever else might have changed since the Civil War, the power dynamic in York County had not. “God damn you,” one Klansman cried out during an attack. “I’ll let you know who is in command now.”

The tormenters concealed themselves beneath robes and horned masks; some of the clothing was dark, some white, some bore crosses or grotesque designs. The man leading this night’s havoc was Dr. J. Rufus Bratton. One local resident and former slave later remembered Bratton as a man who set the “style of polite living” around York County. A father of seven who volunteered to serve as an army surgeon for the Confederacy during the war, Dr. Bratton was the county’s leading physician as well as one of the top officials in its Klan. He brought an agenda with him that night that he shared with only a select number of the other nightriders, a term the press began to apply to the violent men.

Bratton claimed a local black militia led by a man named James Williams was responsible for a rash of fires at white-owned properties. These militiamen, supported by the state and federal governments in an effort to encourage black civic engagement, were not content with a ceremonial status. They swore to avenge the Klan’s growing list of misdeeds and murders, to become a kind of counter-Klan force. During the course of the ride, Bratton rendezvoused with younger members of his order, including Amos and Chambers Brown, sons of a former magistrate, and the four Sherer brothers, who were only formally initiated into the Klan during that night’s ride. When the men met up, they used code words confirming their membership.

“Who comes there?”

“Friends.”

“Friends to whom?”

“Friends to our country.”

Bratton directed this smaller unit of men to the home of Andy Timons, a member of Williams’s militia.

Timons woke to shouts. “Here we come, right from hell!” They demanded the door be opened. Before Timons had a chance to reach it, they broke it from the hinges and grabbed him. “We want to see your captain tonight.”

After beating Timons until he gave up the location of Williams’ home, about a dozen Klansmen rode in that direction. They picked up yet another member of the black militia on their way there; even with the information on Williams’ whereabouts obtained from Timons they needed more help to locate a rural cabin in the dead of night. “We are going to kill Jim Williams,” they told their new guide.

Williams’ offenses in the eyes of Bratton and his co-conspirators predated the formation of the militia. During the Civil War, Williams had been a slave near Brattonsville (a plantation named for Dr. Bratton’s ancestors, and where Bratton himself was born) until he escaped from his master and crossed into the North to fight for the Union army. When he returned to York County after the South’s defeat a free man, he represented an era of new beginnings, “a leading radical amongst the ******s,” as one Klansman groused. He changed his name from Rainey, the name of his former owners, to Williams and headed the militia that vowed to check the Klan’s power.

A few hundred yards from Williams’ house, Bratton brought a smaller detachment of his men to the door. Rose Williams answered, informing them her husband had gone out and she did not know where he was. Searching the house, they only found the Williams children and another man. The raid’s leader was not satisfied that his prize for the night was gone and studied the house with his piercing black eyes.

“He might be under there,” Bratton said of some wood flooring that caught his eye.

They lowered themselves, trying for the most likely spot. Prying up the planks, they found Jim Williams crouched beneath.

Rose pleaded with them not to hurt her husband. They told her to go to bed with her children and marched Williams out of the house. Andy Timons, meanwhile, scrambled to gather the militia to warn Williams, but the Klan’s head start was too great. Bratton had brought a rope with him from town and placed it around Williams’ neck as the group selected a pine tree they decided “was the place to finish the job.” Williams agreed to climb up by his own power to the branch from which they would drop him, but when they were ready to finish the job, he grabbed onto a tree limb and would not let go. One of Bratton’s subordinates, Bob Caldwell, hacked at Williams’ fingers with a knife until he dropped.

Searching the woods later, Timons and Rose found him hanging by the neck. A card on the corpse mocked the militia: Jim Williams on his big muster. Meanwhile, Dr. Bratton rejoined the larger group of Klan riders, who stopped for refreshments at the home of Bratton’s brother, John. One of the Klansmen who had not been on the raid asked where Williams was.

“He is in hell I expect,” replied Bratton.

At Bratton’s brother’s house the secret riders could relax without their disguises, revealing some of the most recognizable and distinguished faces of York County. They could celebrate weakening the will and abilities of their local political enemies through their latest campaign of intimidation. But their actions under the cover of darkness that night—and on many other nights filled with whippings, beatings, sexual assault, and murders—were set to unleash an unprecedented counterattack from the federal government with a single goal: to wipe out the KKK.

K Troop

966

The story of the eradication of the original Ku Klux Klan.

By Matthew Pearl

Lisa Larson-Walker

1.

Sometime after 2 o’clock in the morning, the men cramming into the small cabin lowered themselves to the floor. For a passing moment, they must have looked as though they were conducting a group prayer. They were listening at the floorboards for any rustling, breathing, maybe even whispered pleas for deliverance. Then they tore up the planks. A woman standing near them begged them to stop. Ferociously, they went on, until the floor surrendered its secret.

Earlier that same night, March 6, 1871, the Ku Klux Klan had swarmed the South Carolina upcountry. The rumble of 50-odd men on horseback sounded like an invading force. Membership in the local dens of the Klan, which emerged as a paramilitary terror group after the South’s defeat in the Civil War, thrived in York County. But movements like the Ku Klux Klan feed on fear even in times of strength, and the alarms were ringing out over the growing numbers of black voters in local elections.

That night, the riders went house to house dragging black men out of their beds and forcing them to swear never to vote for “radical” candidates—in other words, those set on protecting their tenuous new rights. The Klansmen’s goals went beyond the vote to the humiliation of these men in front of their families, sending the message that whatever else might have changed since the Civil War, the power dynamic in York County had not. “God damn you,” one Klansman cried out during an attack. “I’ll let you know who is in command now.”

The tormenters concealed themselves beneath robes and horned masks; some of the clothing was dark, some white, some bore crosses or grotesque designs. The man leading this night’s havoc was Dr. J. Rufus Bratton. One local resident and former slave later remembered Bratton as a man who set the “style of polite living” around York County. A father of seven who volunteered to serve as an army surgeon for the Confederacy during the war, Dr. Bratton was the county’s leading physician as well as one of the top officials in its Klan. He brought an agenda with him that night that he shared with only a select number of the other nightriders, a term the press began to apply to the violent men.

Bratton claimed a local black militia led by a man named James Williams was responsible for a rash of fires at white-owned properties. These militiamen, supported by the state and federal governments in an effort to encourage black civic engagement, were not content with a ceremonial status. They swore to avenge the Klan’s growing list of misdeeds and murders, to become a kind of counter-Klan force. During the course of the ride, Bratton rendezvoused with younger members of his order, including Amos and Chambers Brown, sons of a former magistrate, and the four Sherer brothers, who were only formally initiated into the Klan during that night’s ride. When the men met up, they used code words confirming their membership.

“Who comes there?”

“Friends.”

“Friends to whom?”

“Friends to our country.”

Bratton directed this smaller unit of men to the home of Andy Timons, a member of Williams’s militia.

Timons woke to shouts. “Here we come, right from hell!” They demanded the door be opened. Before Timons had a chance to reach it, they broke it from the hinges and grabbed him. “We want to see your captain tonight.”

After beating Timons until he gave up the location of Williams’ home, about a dozen Klansmen rode in that direction. They picked up yet another member of the black militia on their way there; even with the information on Williams’ whereabouts obtained from Timons they needed more help to locate a rural cabin in the dead of night. “We are going to kill Jim Williams,” they told their new guide.

Williams’ offenses in the eyes of Bratton and his co-conspirators predated the formation of the militia. During the Civil War, Williams had been a slave near Brattonsville (a plantation named for Dr. Bratton’s ancestors, and where Bratton himself was born) until he escaped from his master and crossed into the North to fight for the Union army. When he returned to York County after the South’s defeat a free man, he represented an era of new beginnings, “a leading radical amongst the ******s,” as one Klansman groused. He changed his name from Rainey, the name of his former owners, to Williams and headed the militia that vowed to check the Klan’s power.

A few hundred yards from Williams’ house, Bratton brought a smaller detachment of his men to the door. Rose Williams answered, informing them her husband had gone out and she did not know where he was. Searching the house, they only found the Williams children and another man. The raid’s leader was not satisfied that his prize for the night was gone and studied the house with his piercing black eyes.

“He might be under there,” Bratton said of some wood flooring that caught his eye.

They lowered themselves, trying for the most likely spot. Prying up the planks, they found Jim Williams crouched beneath.

Rose pleaded with them not to hurt her husband. They told her to go to bed with her children and marched Williams out of the house. Andy Timons, meanwhile, scrambled to gather the militia to warn Williams, but the Klan’s head start was too great. Bratton had brought a rope with him from town and placed it around Williams’ neck as the group selected a pine tree they decided “was the place to finish the job.” Williams agreed to climb up by his own power to the branch from which they would drop him, but when they were ready to finish the job, he grabbed onto a tree limb and would not let go. One of Bratton’s subordinates, Bob Caldwell, hacked at Williams’ fingers with a knife until he dropped.

Searching the woods later, Timons and Rose found him hanging by the neck. A card on the corpse mocked the militia: Jim Williams on his big muster. Meanwhile, Dr. Bratton rejoined the larger group of Klan riders, who stopped for refreshments at the home of Bratton’s brother, John. One of the Klansmen who had not been on the raid asked where Williams was.

“He is in hell I expect,” replied Bratton.

At Bratton’s brother’s house the secret riders could relax without their disguises, revealing some of the most recognizable and distinguished faces of York County. They could celebrate weakening the will and abilities of their local political enemies through their latest campaign of intimidation. But their actions under the cover of darkness that night—and on many other nights filled with whippings, beatings, sexual assault, and murders—were set to unleash an unprecedented counterattack from the federal government with a single goal: to wipe out the KKK.