TELL ME YA CHEESIN FAM?

I walk around a little edgy already

Scientists have revived a 'zombie' virus that spent 48,500 years in permafrost

Warmer temperatures in the Arctic are thawing the region's permafrost — a frozen layer of soil beneath the ground — and potentially stirring viruses that, after lying dormant for tens of thousands of years, could endanger animal and human health.

To better understand the risks posed by frozen viruses, Jean-Michel Claverie, an Emeritus professor of medicine and genomics at the Aix-Marseille University School of Medicine in Marseille, France, has tested earth samples taken from Siberian permafrost to see whether any viral particles contained therein are still infectious. He's in search of what he describes as "zombie viruses" — and he has found some.

Jean-Michel Claverie is pictured here working in the subsampling room at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Postsdam, where the cores of permafrost were kept.

The virus hunter

Claverie studies a particular type of virus he first discovered in 2003. Known as giant viruses, they are much bigger than the typical variety and visible under a regular light microscope, rather than a more powerful electron microscope — which makes them a good model for this type of lab work.

His efforts to detect viruses frozen in permafrost were partly inspired by a team of Russian scientists who in 2012 revived a wildflower from a 30,000-year-old seed tissue found in a squirrel's burrow. (Since then, scientists have also successfully brought ancient microscopic animals back to life.)

In 2014, he managed to revive a virus he and his team isolated from the permafrost, making it infectious for the first time in 30,000 years by inserting it into cultured cells. For safety, he'd chosen to study a virus that could only target single-celled amoebas, not animals or humans.

He repeated the feat in 2015, isolating a different virus type that also targeted amoebas. And in his latest research, published February 18 in the journal Viruses, Claverie and his team isolated several strains of ancient virus from multiple samples of permafrost taken from seven different places across Siberia and showed they could each infect cultured amoeba cells.

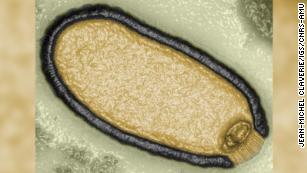

This is a computer-enhanced microphoto of Pithovirus sibericum that was isolated from a 30,000-year-old sample of permafrost in 2014.

Those latest strains represent five new families of viruses, on top of the two he had revived previously. The oldest was almost 48,500 years old, based on radiocarbon dating of the soil, and came from a sample of earth taken from an underground lake 16 meters (52 feet) below the surface. The youngest samples, found in the stomach contents and coat of a woolly mammoth's remains, were 27,000 years old.

That amoeba-infecting viruses are still infectious after so long is indicative of a potentially bigger problem, Claverie said. He fears people regard his research as a scientific curiosity and don't perceive the prospect of ancient viruses coming back to life as a serious public health threat.

"We view these amoeba-infecting viruses as surrogates for all other possible viruses that might be in the permafrost," Claverie told CNN.

"We see the traces of many, many, many other viruses," he added. "So we know they are there. We don't know for sure that they are still alive. But our reasoning is that if the amoeba viruses are still alive, there is no reason why the other viruses will not be still alive, and capable of infecting their own hosts."